|

This is Jacket # 2 | # 2 Contents | Homepage | Catalog | |

|

|

Every consideration of James Laughlin and New Directions must begin with The List: a list that is numbing to recite, overwhelming in its whole, and astonishing in its particulars. New Directions was the publisher - and almost always the first publisher in the United States - of Apollinaire, Djuna Barnes, Bei Dao, Borges, Paul Bowles, Brathwaite, Brecht, Camus, Cela, Céline, Cendrars, Char, Cocteau, Dahlberg, Daumal, Durrell, Eluard, Endo, Garcia Lorca, Hawkes, Hesse, Huidobro, Isherwood, Jarry, Joyce, Kafka, Lautréamont, Merton, Michaux, Henry Miller, Mishima, Montale, Nabokov, Neruda, Parra, Pasternak, Paz, Queneau, Raja Rao, Reverdy, Rilke, Rimbaud, Sartre, Sebald, Supervielle, Svevo, Tabucchi, Dylan Thomas, Ungaretti, Valéry, Vittorini, Nathanael West, and Tennessee Williams. At a time when they were half-forgotten - it seems incredible now - ND brought back into print Henry James, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Evelyn Waugh, E.M. Forster, William Faulkner. For decades it had the only editions of Baudelaire and Rimbaud. And New Directions was, and continues to be, the Central Station for American avant-gardist poetry: Pound, Williams, H.D., Rexroth, Patchen, Oppen, Reznikoff, Olson, Duncan, Creeley, Snyder, Levertov, Ferlinghetti, Corso, McClure, Rothenberg, Antin, and on to a new generation, represented by Michael Palmer, Susan Howe, Forrest Gander. Laughlin was more than the greatest American publisher of the 20th century; his press was the 20th century. Every writer has a tale of conversion - "the book that made me want to become a writer" - and for nearly every writer I know, that one book was published by New Directions: Amerika, Nausea, Nightwood, A Season in Hell, among them, or even A Coney Island of the Mind. I belong to the last generation to come of age before the tidal wave of the over-production of everything. In my adolescence, the black and white photographic covers of ND books were unmistakable on the bookstore shelves, and I would buy any of them at random, knowing that if ND published it, it was something that had to be read. Laughlin’s success is usually attributed to his wealth, which is only part of the story. He was, of course, an heir to a steel fortune: the huge sign of Jones & Laughlin used to dominate the cliffs of Pittsburgh. In an interview a few years ago, he casually mentioned that on the day he graduated Harvard in 1936, his father gave him $100,000 to start out in the world. [My parents in 1936 both had good jobs, were living a modest, urban middle-class life, and their combined income was $2000 a year.] The young Laughlin was tall, handsome, athletic, and extremely rich, and could easily have become a playboy. In fact, he did become a playboy, but a playboy devoted to literature. |

|

|

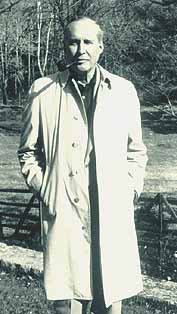

James Laughlin One must understand the milieu from which Laughlin came: the steel barons of Pittsburgh; the Mellons, Carnegies, Fricks. Scottish Presbyterians, they counted every penny as they spent millions. Their philosophy was articulated in a book by Andrew Carnegie with a priceless title, The Gospel of Wealth, and it was a combination of paternalism and charity. Wealth was not for personal enjoyment, but was to be held "in trust," and dispensed according to the wisdom of the man intelligent enough to have earned it. This meant, on the one hand, that the Mellons, Carnegies, and Fricks were lavish in endowing the universities, foundations, museums, symphony halls, and hospitals that still bear their names. On the other hand, they could be ruthless when their metaphorical children became unruly, quite openly arranging for the repression of strikers and the assassinations of union leaders in the steel mills. Although James Laughlin never paid for the murder of any writer - even the writers of book reviews - he did dedicate his fortune to good works. Only a few other wealthy heirs have been involved in publishing ventures, all of which were either short-lived or quickly turned into commercial enterprises. Money is usually wasted on the rich. Laughlin not only devoted his life to the unglamorous pursuit of making books, he also, almost uniquely, did not name his press after himself. His only sign of self-monumentalization was a small line that appeared on the copyright page of every book, with a strange preposition: "New Directions books are published for James Laughlin." Not by: for. It was a tip of the hat to the legacy of Andrew Carnegie. His wealth could have led to a long list of mediocrities. That it did not was due not only to his evident literary acumen, but to his modernist commitment to the "new," his knowledge - now extinct among American editors - of various European languages, and his willingness to listen to writers (not critics, reviewers, agents, and makers of buzz) in the search for new writers. Laughlin’s life is a tangle of paths: His prep school classics teacher, Dudley Fitts, put him in touch with Pound, who led him to William Carlos Williams, who led him to Nathanael West. Pound led to Henry Miller who led to Hesse’s Siddhartha, the blockbuster that supported dozens of obscure poets. Williams led to Rexroth who led to Snyder who led to Bei Dao; Dame Sitwell to Dylan Thomas; Eliot to Djuna Barnes; Tennessee Williams to Paul Bowles. Moreover, he was a fundamentalist believer in Pound’s dictum that it takes at least twenty years for a writer to be recognized. (Today it is either twenty minutes or forty years.) While other publishers treat their titles like fresh fish, New Directions has been the only one to keep almost all its books in print for decades. It was another forgotten legacy of 19th century capitalism - the idea of the long-term investment - and it eventually paid off. Yesterday’s bizarre gibberish is now on the final exam. Neither large nor small, New Directions survives as the last important independent literary publishing house in the United States, and the only for-profit one I know that has never published a book to make money. And yet it makes money. New Directions is a lesson that no one has learned, the tortoise making its way past the ruins of zillion-dollar contracts and publicity campaigns for the books that only some want today and no one will want tomorrow. Ezra Pound told the 20-year-old James Laughlin that he would never be a poet, and that he should do something useful, like publishing. Pound - who usually was remarkably skillful in discovering young writers - was so wrong in this case that one suspects him of acting out of self-interest. Laughlin continued to write, but for most of his life he kept it a half-hidden secret. Only in recent years did he begin to regularly publish what turned into a small mountain of poems, essays, memoirs, and fiction. |

|

|

In his poetry, he evolved an unadorned and direct speech learned from Greek and Latin and from Williams and Rexroth. He invented the only new prosodic form in American poetry since Williams’ three-stepped line: each line, composed on the typewriter, cannot be more than one letter-space longer or shorter than the previous line. It was a crackpot idea that worked. Along with Rexroth, he was the author of long, narrative, autobiographical poems that remain pure poetry while being as readable as prose. And he wrote, following his Greek, Latin, and Sanskrit masters, perhaps the only witty erotic American poetry in this century. (It is a curiosity of American poetry that its greatest heterosexual erotic poetry has tended to be written by men and women in their old age.) Now that the poets can no longer demand that Laughlin read them, perhaps they will begin to read him. His prose style is a strange and highly entertaining combination of an erudite speaking in plain American, a Joycean addicted to puns, and the kind of language one hears in the screwball comedies of the 1930’s - the slang of those fast-talking eccentrics in tuxedos. There is nothing like his critical writings, especially now, when literary critics employ a language more suited to that of astrophysicists. James Laughlin was the last American veteran of the revolution of the word, the last with personal memories of all the masters of modernism. He changed Gertrude Stein’s flat tire, identified Dylan Thomas’ body in the morgue, shipped ballet shoes to Céline’s wife after the war, was saved from falling off a cliff by Nabokov’s butterfly net, paid for Delmore Schwartz’s shrink and Pound’s legal defense, smuggled Merton out of the monastery to go drinking.

He lived from the First World War to the First World Web, the

eighty monstrous years on the planet in which all younger writers

wish they had lived. He had the self-deprecation of the unusually

tall; he would disappear for months to go skiing at Alta, the

resort he founded; he was obsessed with doppelgängers, though

few mortals were his size; his mannerisms were oddly reminiscent of

George Bush; his personal library was unparalleled and he had read

it all; he used to golf with James J.Angleton; he had a passion for

India; he was an athlete and a hypochondriac; he sent Clinton -

whom he called "Smiley" - a copy of Pound’s ABC of

Economics as an inaugural gift; he was self-absorbed and generous,

hedonistic and depressive, obstinate and remarkably receptive;

those he published and those he didn’t never stopped

complaining about him; sheep grazed on his lawn in

Connecticut. Photos of James Laughlin courtesy New

Directions,

|

|

J A C K E T # 2 Contents page This material is copyright © Eliot Weinberger

and Jacket magazine 1997

|