|

In her understanding, the lyric is truly a speculative field: that is to say it is constituted of imaginative speculations the aesthetic autonomy of which is never gratuitous sociolect, not even for a syllable.

¶

Literariness of non-imitative lyric is to be assumed, and in Guest the language of her language writing is already literary in part because it is constituted of the literature she reads, in part because it foregrounds the condition of literariness. In other words, she is not embarrassed to be found reading a book, raking a book for its themes and sensibility. With defamilarized romance made fragmentary as her decided bias, Guest supplies only nomenclature, isolated and disjunctive, or sensuous place names held in suspension and disequilibrium. Motifs straight from the manse are allowed to remain uncanny fixities in an otherwise unfixed domain of text. Meanwhile she leaves traces of lyricism so imaginatively acute that a moral rectitude is the precipitate. Literariness from book rather than nature is her domain. For Guest, literariness is the estate of language in perpetual doubling, in perpetually multiplying conjugation of images - those narratives left in scraps which, neither waste nor wasteland, condense abstract song.

More apt to yield verbal delirium than noise-music, Guest's lyrical pulse brings early modern materiality of language into vital relation with the free-ranging experiment that is lyric.

With Guest's literary poetics, there is no recreation of the illusion of history. Historical verisimilitude is kept at bay through a focus on the textual centrifuge into which all facts are put. The verbal construction is again the object in question. As for artifice in story, let us remember that auteur of cinema, Erich Rohmer, with his installation of painted flats instead of actual landscape through which Perceval rides astride an actual horse - this scenography coincident with the imaginary domain. As for Guest, medieval romance is already given as text, not history - which means, in her poetics, surface and facture, not illusion, are the protagonists to the rescue. A masterpiece of such textual facture so dense as to become a transfigured tapestry is surely "The Knight of the Swan," from Moscow Mansions (Viking, 1973). "Garment," from Quill, scored for verbal melodies and rhythms on the page, provides a recent example of the theme of haptic touch given linguistic privilege. From the same book, "Fell, Darkly" enacts its own complexity, a complexity integral with multi-register heterogeneous modernity. An epigraph from Joyce about withdrawing regard from clairvoyance shows that resisting the lyricism through tactics of difficulty is Guest's intention. It is also a practice in a poetics at which she excels.

The verbal construction is again the object in question. As for artifice in story, let us remember that auteur of cinema, Erich Rohmer, with his installation of painted flats instead of actual landscape through which Perceval rides astride an actual horse - this scenography coincident with the imaginary domain. As for Guest, medieval romance is already given as text, not history - which means, in her poetics, surface and facture, not illusion, are the protagonists to the rescue. A masterpiece of such textual facture so dense as to become a transfigured tapestry is surely "The Knight of the Swan," from Moscow Mansions (Viking, 1973). "Garment," from Quill, scored for verbal melodies and rhythms on the page, provides a recent example of the theme of haptic touch given linguistic privilege. From the same book, "Fell, Darkly" enacts its own complexity, a complexity integral with multi-register heterogeneous modernity. An epigraph from Joyce about withdrawing regard from clairvoyance shows that resisting the lyricism through tactics of difficulty is Guest's intention. It is also a practice in a poetics at which she excels.

Joyce has deployed the mellifluous at the expense of sentimentality yet has understood how to thicken the text with historical and linguistic content so the lyric may be an instrumentality for complex bardic utterance. Also among our avowed mentors of textual matter is Mallarmé, and it is in response to Mallarmé 's assumption that the world exists to exist in a book -

'. . . everything in the world exists in order to end in a book.'

[' . . . tout, au monde, existe pour aboutir à un livre.']

-- with his elliptical yet fastidious spatialization of text worth silos of more recent pretense to modernity - that Guest can be found to be a consummate investigator.

In transitory states throughout space, the signifying matter of her compositions realized on the page is at least as judicious as it is refined, and Guest's poetry is distinguished by a sound cosmopolitanism. Thus Guest exposes decorousness for what it is: the weak misreading of a lyrical idea on display in unrealized verse. In her hands, by contrast, lyric maintains its intellectual focus on the poetics of non-imitative, writerly text. The constructed surface of abstract sensuous posits and their recombinatory situation erect something modern of the residues of lyrical poetry.

¶

To the objection that at the end of the twentieth century the lyric is wasted, attenuated in its capacity to interpret, that it cannot incorporate idea but only sensibility, there is the developing body of poetry, heard first and written second, that would refute this. Very different from Guest is, for instance, Anne-Marie Albiach's lyrical voice. Indeed, in her "Vocative Figure" (1985; English translation, published by A-B, revised, second edition, 1992) the voice is marked; its subject of address - you - gives concrete expression to the voice, the utterances of which define themselves by directing attention to the other, in intimacy. "Vocative Figure" then, identifies lyric with marked address.

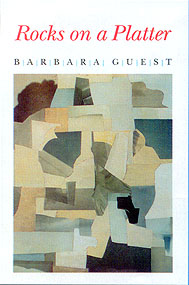

Guest, as we have said, puts the lyric at the service of a very different cause. Not speech but writing - together with all the assumptions about the poetics of writing and the already written - informs the literariness to which the aestheticism is put. The lyric becomes the occasion for considering the literary status of nature through re-interpretive cultural designs. In this regard, brief mention may be made of her manuscript and forthcoming book, Rocks on a Platter (Wesleyan University Press, 1999). The first page in its entirety reads:

|

|