|

But as both A.L. Nielson and Lorenzo Thomas pointed out, the tendency to read the Black Arts Movement in terms of radical political positions and speech/music based poetry neglects the movement’s intellectual and textual foundation. Both, after all, use techniques of collaboration, linguistic rupture and syntactical complexity to make points about the relationship between power and language — but towards different ends. Watten’s syntactical ruptures seek to free poetry from the illusion machine of meta-narrative, meaning, and depth. He exposes language’s ties with imperial and oppressive power structures by radically altering the way content is read and understood by readers.

Baraka has sought to convey the struggles of real people, and himself, by writing that uses language not to alienate but to educate; to inform and mobilize readers to stand up and fight the imperial powers that work to keep them silent. Baraka perceived Watten’s poetics as a ‘struggle free intellectualism,’ free of the commitments to real people who put their lives on the line to fight back against oppressive power structures.

But it was not just Watten against whom Baraka was airing his frustrations — it was the whole conference and what he perceived to be academics that ‘turn the struggles of real people into post-modern subjects in order to get tenure."

However, in spite of the conference’s attempted focus on the 1960s, Watten’s talk was one of the few to actually attempt a contextualizing framework of the decade — not bad for a poet who seeks to subvert direct referentiality in his work. The question he attempts to answer — ‘without resting on transparency or homology, how does it make sense that the Free Speech Movement is a historical precursor of the Language School?’ — is itself a perplexing paradox. After all, how can a ‘school’ that has at its most fundamental level questioned representation then attempt to firmly situate itself within a specific historical moment? And although he ultimately has to resort to a clear presentation of certain historical facts (is that really such a bad thing?), essentially the paper succeeds in reading language poetry’s poetics into the cultural politics of the 1960s. History is, after all, open to interpretation and revision.

In October 1964, after being forbidden from demonstrating on Telegraph Avenue, several thousand students at the University of California at Berkeley participated in a thirty-two hour stand-off with police and university officials. Out of this action, the students — under the leadership of philosophy major Mario Savio — formed the Free Speech Movement (FSM). In December 1964, on the steps of the administration building, Savio attempted to speak out against the bureaucracy of the university. Savio was silenced by the officials, and led off by police. Hundreds of students stormed the building to stage a sit-in, and were arrested. FSM was a major catalyst in solidifying student demonstrations at college campuses across the country (Tindall, 1373).

In investigating the Free Speech Movement as one of the primary catalysts for his own poetic practice, Watten observed that the prohibitions of speech during this time were designed to ‘alienate the student movement from the liberal institutions it wanted to engage.’ Watten played a clip of the Berkeley officials stating that the students who were trying to speak were doing so ‘merely for the sake of crisis; speaking only for their own form of utopia....We have a program which had been approved.’ Since the limitations of speech were tested when any attempt to speak fell on mute ears, the articulation of social anger had to be voiced outside of social structures.

Watten used Ginsberg’s powerful retort — chanting instead of answering a reporter’s questions — as an example of this. Because representation through speaking is impossible, Ginsberg is free to do whatever he wants to answer a question. His chanting mirrors the breakdown of language happening at the time. The signifier (speaking) had become empty, and Ginsberg could fill it in with chanting — thus making a much more confrontational statement than any words could have made.

In the discussion that followed Watten’s talk, Baraka challenged Watten’s reading of Ginsberg as denying the spiritual point he was trying to make through his chanting of Buddhist mantras on national TV. A chant is not an empty signifier; in fact, it is full of religious connotations that work to situate the poet on a higher plane of reality — a linguistic speaker-of-tongues, an anti-material sage, a wise guru.

Although citing Ginsberg was enough to get him into trouble, Watten had also described Mao’s Little Red Book as an empty signifier. Watten showed a clip of a former Black Panther talking about how some members of the movement acquired guns. He described how they bought pamphlets of the Little Red Book in Chinatown for 20 cents, and then sold them to the Berkeley students for $1.00. The former panther (interviewed for a PBS documentary) said that they hadn’t really even read the book — they just know that the kids were into it, and that they could make a profit selling them. So, Watten surmised, removed of its cultural context Mao’s book was filled in with another signifier — in this case, making a profit to buy guns to start a revolution.

But again Baraka retorted: the Little Red Book is not an empty signifier — it facilitated a major change in a political system; it represented the possibility of overthrowing one system and exchanging it for another. Its context is fixed. And besides, this is just one man who said he hadn’t read the book. We read Mao, Baraka insisted.

However, Watten’s reading of the empty signifiers that speech had become during this time (and on a more theoritical level, his attempt to read the political climate of the 1960s through Laclau to map out which cultural events fell under categories of irrational and rational) was an interesting contextualization of language poetry.

But it is important to note that empty signifiers are now a marketing technique. If anything has changed from the 1960s to the 21st century it is that signifiers are now so empty that TV advertising can match up a hamburger with an Aretha Franklin song, a revolutionary slogan with a pair of tennis shoes, and it all somehow makes sense. Advertising, which only ten years ago was inventing ‘subliminal’ images to sell products (remember the camel’s penis?) now has turned the subliminal inside out, disconnecting the product from the message and mocking itself before it can be mocked. Bob Grenier’s concise declaration ‘I hate speech’ — in response to the empty signifier that speech had become in the 1960s — now could be a billboard for iMacs.

Watten’s presentation was done from his laptop computer in which he had loaded video clips from a PBS documentary on the student movement, stills from Ginsberg’s India Journals, and outlines of his main points. While his technological savvy was almost sexy, it is important that the message he was conveying not be read separately from the technology he used to get his point across.

The artist Julian Laverdiere comes to mind, particularly his gigantic replica of the ship that sank while making the first attempt to lay trans-Atlantic telegraph cables.

The ship is encased in a bluish purple glass case which is in turn entombed in a high-tech black monument that resembles a space-age stereo system. Like looking with a flashlight at the carcass of a ship decaying at the bottom of the ocean, you only see parts of it unveil through the tinted glass as you walk along the elevated platform. Basically, it is an image of decay encased in technological wrappings, and its antiquity contrasts with the ultra-modern presentation within which it is situated. Even more to the point, the decayed ship is contained within the technology that it helped to launch. Poet and art critic Tim Griffin writes that it represents, ‘the dead past inside the living present, the histories inside history, and the history being made."

Watten’s talk was similar. He attempted to reconstruct a counterculture history by encasing it in a technologically sleek package. Projecting video images of the Berkeley riots from his PC laptop against the huge screens, the cries of protest blaring through the auditorium’s stereo system made the historical moment mesmerizing and alive — but simultaneously, presented in a hyper-rational mode that made it endorsed, official, and unable to exist outside of the sleek packaging: the dead past inside the living present.

The revolution of the 1960s paved the way for the language of the technological revolution of the 21st century. In his attempt to situate a contextual history for language poetry, Watten neglects the totalizing impulses that necessitate the drive towards establishing such a history. And unwillingly, he becomes a participant in the very authoritarian structures that he seeks to undermine.

This is not to say that technology shouldn’t be used to present poetry — it is a fact of many of our lives and should be used to facilitate any and all forms of communication, including poetry. But there is a way of using technology that divorces it from its corporitized PowerPoint purpose of assembling and packaging information. Watten of all people should understand this — the PC is another kind of language, and it too needs to be ‘turned upside down’ so that the message it is carrying does not reinforce the corporate program. In ‘The Conduit of Communication in Everyday Life’ Watten wrote, ‘One can gain access to the structure of recurrence and feedback that produces the everyday by understanding the forms of communication through which its form are inculcated in both the person and language.’ (35)

Technology is the foundation of our current communication, and it is pounded into our heads everyday. If the form of Watten’s critique had better reflected the structures of communication he was using, his claims towards poetry’s ability to undermine systems of representation might have carried more weight.

It is after all the communications revolution that has led to the demise of speech. At this point alienation is so extreme that it is absorbing. Now we don’t know what to do unless we are alienated from speech, from our environment, from our locality.

East of Orono, the small independently run shopping center in Bethel, Maine is going out of business — people would prefer to drive 45 minutes to the wedding cake coliseum mall, a prototype that appears in almost every American city. As during the 1960s, there are cultural circumstances that shape the theoretical parameters of poetry. These need to be identified, absorbed, rejected, and re-articulated.

One of Baraka’s points was that to situate struggle in the past is denying the fact that there is still a lot of struggling going on, and still a long way to go. Baraka’s monthly salon at his home in Newark, NJ (his birthplace to which he returned in 1966), continues to be a model for how local communities are a form of resistance to the alienation that has seized urban environments. At these salons, Baraka stresses the necessity of small magazines and chapbooks to perpetuate art and culture as a visible means of resistance. After a lively evening of readings, rants, and music, people socialize in the kitchen over beans and rice. The energy around these salons makes it clear that it is poetry’s live engagement with the conditions that surround it which helps keeps a countercultural spirit alive.

***

There is something between the extremes of Baraka and Watten that is extremely pertinent to the times. There are the empty signifiers used by the mass media that point to a dramatic shift in the way that meaning is understood and produced by the culture — Watten’s theories help to illuminate these, and to read them as a site of potential poetic awareness.

Yet, there are cultural and political realities that the constant questioning of representation in language cannot appropriate. Hip hop’s widespread cultural success brings signifiers that are not at all empty to a mass audience. At a recent Dead Prez concert, a half-and-half mixture of black and other chanted ‘Kill the Police’ while a slideshow depicting policeman, white politicians, and images of prisons flashed in the background. There nothing empty about the police brutality witnessed in across the country to which these songs very blatantly refer.

There is information to be gained from both speech and language — and this information contains the function and form of poetry in the 21st century. As Alan Gilbert recently wrote, ‘form is never more than an extension of culture.’ And culture is as loaded as an empty signifier looking for a trigger.

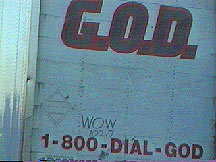

On the drive back from Orono, passing through Kerouac’s birthplace — Lowell, MA — Liz Willis and I came upon a truck with a message on the back that read: 1-800-G.O.D. We assumed it was some Jesusmobile, a traveling evangelistic roadshow. But we had forgotten that GOD can go either way — can be either empty, or full, depending on the context.

We then passed the truck’s left side, which read ‘Guaranteed Overnight Delivery.’ Wow. Welcome to the 21st century, where alienation from meaning is no longer avant-garde. Guaranteed.

|