|

HANNAH WEINER has been so much a part of my life as a writer that I find that her death hasn’t ended my relation to her but moved it into another dimension. I don’t mean anything supernatural about that — I always played the resolute skeptic to Hannah’s more heterodox beliefs; but I never doubted that she was a visionary poet, and I found her insistence on her clairvoyance to be a welcome relief from the heavy-handed rhetoric of poet as prophet that she so utterly rejected.

While Hannah befriended, and was admired by, many poets of my own generation, her poetry begins to make a different sense when considered in the context of some of the poets of her own generation. Like many of these poets, she was deeply influenced by Eastern thought and in search of a poetry of everyday life. In this, her project resonates with Ashbery, Mac Low, Guest, Ginsberg, Eigner, Creeley, Wieners, and Schuyler. Like Jack Spicer, she understood that if the heart of poetry were a radical foregrounding of the medium of writing, then this would also mean that the writing, and possibly the writer, became a medium. But a medium of what, for what? One of Hannah’s most enduring achievements as a writer was her unflinching, indeed often hilarious, inclusion of what, from a literary point of view, is often denigrated as trivial, awkward, embarrassing, silly, and, indeed, too minutely personal, even for the advocates of the personal in writing.

While Hannah befriended, and was admired by, many poets of my own generation, her poetry begins to make a different sense when considered in the context of some of the poets of her own generation. Like many of these poets, she was deeply influenced by Eastern thought and in search of a poetry of everyday life. In this, her project resonates with Ashbery, Mac Low, Guest, Ginsberg, Eigner, Creeley, Wieners, and Schuyler. Like Jack Spicer, she understood that if the heart of poetry were a radical foregrounding of the medium of writing, then this would also mean that the writing, and possibly the writer, became a medium. But a medium of what, for what? One of Hannah’s most enduring achievements as a writer was her unflinching, indeed often hilarious, inclusion of what, from a literary point of view, is often denigrated as trivial, awkward, embarrassing, silly, and, indeed, too minutely personal, even for the advocates of the personal in writing.

For Hannah Weiner, nothing was too minute to merit recording, but she decisively rejected all the extant literary models for recording personal thoughts or feelings — from the single-voice lyric to the narrative-driven diary. The motivation for Hannah’s charting of her personal space was not primarily self-expression — any more than the motivation for Descartes’s meditations were primarily self-expression. Rather, she used her self as the most ready-to-hand site for her experiments on the relation of language to consciousness. Hannah’s work is an unrelenting synthesis of radical formal innovation and intensely personal content. Her best-known work remains The Clairvoyant Journal (Angel Hair, 1978), where she used a three-voice structure to record not only her own diaristic impressions and notations but also — scored in italics — a voice commenting on what she had written and — in capital letters — giving commands to her. This highly original fugal structure — an explicit alternative to the more conventional monologic forms — found vivid realization in the three-person performances that she gave in the 1970s and 1980s.

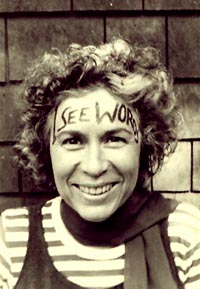

Hannah Adelle Finegold was born in Providence, Rhode Island on November 4, 1928. She graduated from Classical High School in 1946 and went on to Radcliffe College, class of 1950 (magna cum laude), where she wrote a dissertation on Henry James. After several jobs in publishing, she became an assistant buyer at Bloomingdale’s. In the meantime she married a psychiatrist; the marriage ended in divorce after four years. Subsequently, Weiner got a job designing lingerie. She began to write poetry in 1963. Her best known work of this period is The Code Poems (Open Studio, 1982), written using the international code of signals (nautical flag signals). These works were also the basis of performances she gave in the 1960s and she was a participant in the downtown performance scene of the time. After 1970, she devoted herself to writing, emphasizing that all her works written after 1972 were based on ‘seeing words’. As she says in an epigraph to The Clairvoyant Journal: ‘I SEE words on my forehead IN THE AIR on other people on the typerwriter on the page." Her other books include Little Books/Indians (Roof Books, 1980), Spoke (Sun & Moon Press, 1984), Silent Teachers / Remembered Sequel (Tender Buttons, 1993), and We Speak Silent (Roof, 1997).

It is an irony, perhaps, that the writing that Hannah will be best remembered for coincided with a period in which schizophrenia made her everyday life increasingly difficult. Hannah’s illness was often shrugged off as eccentricity, as in we’re all a little crazy after all. But few us suffer from our craziness in the way Hannah did and her schizophrenia was not merely metaphoric, despite the fact that Hannah did not accept any characterization of herself as mentally ill. Surely there was the fear that since Hannah’s work was predicated on hearing voices and seeing words, her identification as schizophrenic would discredit the achievement of a poetry in which the very idea of a stable, expressive lyric self is exploded into what might, indeed, metaphorically be described as a kind of schizophrenic writing. This may be less a problem for work such as James Schuyler’s, where mental illness is explicitly figured, or for writers like Holderlin, in his late poems, or Wieners, where the lyric voice may be read as a kind of sanctuary from schizophrenia. In any case, Hannah Weiner’s work is not a product of her illness but an heroic triumph in the face of it. Her personal courage in refusing to succumb to what often must have been unbearable fear induced by her illness, her persistence in writing in spite of her disabilities, is one of the legacies of her work. And if her schizophrenia gave her insight into language, into human consciousness, into the nature of how everyday life can be presented rather than represented in writing — well, we all have to start from where we are.

While Hannah’s last few years weren’t easy, she continued to produce amazing writing, pushing her own poetry and the possibilities for poetry into new zones of perception. What else are poets for?

|