|

Jacket 15 — December 2001 | # 15 Contents

| Homepage | Catalog | |

Olivier BrossardInterview with Steve Clayof Granary Books, Friday 2 February, 2001This piece is 6,500 words or about fifteen printed pages long. |

|

¶

Olivier Brossard: I would like to start with a question that might seem pretty obvious: where does the name Granary come from? Why such a name? What does it imply in terms of public image, in terms of publishing activity? |

| |

Photo of Steve Clay |

|

Steven Clay: Well, actually the name has Midwestern roots. Granary Books began in St. Paul, Minnesota, a location which is known as the breadbasket of America — so the concept of Granary had to do with a sense of storage, ripening, and distribution. Granary was framed as a distributor of finely made books rather than as a publisher per se. ¶ OB: Did the name Granary not take a relief of its own, did it not stand out when you moved to New York? When did you first move here? SC: January 1st 1989, and I think the name is much more interesting in the context of New York than in the context of the Midwest — it’s not exactly ironic but it is out of place, out of step. It’s such a familiar word to me now I don’t even think about it, but I do recognize that it has an unfamiliar character to it. Interestingly, another person from Minnesota, a musician named Bob Mould, moved to New York shortly after I did. He started a music company called Granary Music; so for a while I was getting all of his phone calls! Granary Music was operating out of Brooklyn for a few years but I believe he’s moved on because I have not had anyone asking for Granary Music in some time. ¶ When did you decide to begin publishing books and when did Granary Books start as a publishing house? What was the general context of publishing when you started out? Was it favorable to independent publishing ventures? Well, like all kinds of independent enterprises, I sort of backed my way into it, there was no grand plan, there was really not even a concept of publishing. I was very interested in the ways in which writing was distributed on the margins, the kind of sociology of book distribution among small presses, and the poets who were producing work that was primarily published in small presses. How did that stuff get around? So, I was interested in publishing but also in bookselling, particularly in places like the Phoenix Book Shop, the Eighth Street Book Shop, Asphodel, Serendipity, Sand Dollar, Gotham and City Lights. These were kind of emblematic places for me and in my imagination they were very much tied to the writing because it was all part of a community activity that included writing and printing and publishing and distributing and talking and reading, and so forth.

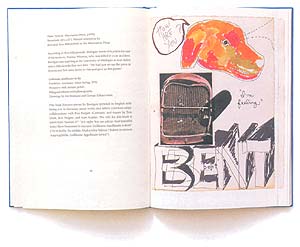

from Kenward Elmslie and Trevor Winkfield, Cyberspace The first publishing that Granary did was completely ephemeral. There was no real ambition behind it, it was just to produce a little broadside, then another little broadside — there was never a plan at all. I make this very clear in the introduction to Granary’s catalogue [When will the book be done?] — it was nothing you know, it just barely existed. However, there was a point at which it did transition into something that was more serious in its ambition, more self-conscious as a project, and that really began with the book called Nods, which was a text by John Cage and drawings by Barbara Farhner. That was 1991. |

|

¶ What was the importance of publishing Nods? In When will the book be done? you talk about “a procedural approach” and more precisely about “the seemingly disparate elements of publishing” that you are interested in. Based on that book [Nods], what kind of publishing logic did you become involved in? Well, Granary Books had been acting as a distributor until then, primarily distributing literary works that were produced in fine editions. Generally, they were letterpress editions, books that paid a lot of attention to the crafts of bookmaking — printing, papermaking and book binding. Maybe they were a little bit heavy on the side of the crafts, on the making of the book, but nonetheless it seemed like the right way of working for me. Let me interject that, at the same time, I was equally interested in all kinds of book production — offset, mimeo, photocopy — the ways in which books were made were very interesting to me, but I happened to be in a situation where the books that I was dealing were made, by-and-large, via letterpress on fine paper, and well-bound. So, when Nods came along, the idea for Nods, which evolved from a conversation with Barbara Farhner, walking down the street, you know — the fact is we recognized, simply, that John Cage was alive and living on 6th Avenue and 18th Street and that we could probably call him up and ask him to do a book! — it was that naive in a way, that was the simplicity with which we approached it. ¶ Walking down the street, the idea that you could phone up John Cage: I am interested in this idea of spontaneity. Is it one of Granary’s “guiding principles”? I would say definitely, yes. One of the hardest questions for me to answer is the one which comes on the phone when someone asks, “How do I submit a project for publication at Granary Books?” I mean, there’s no answer, there’s no policy, it just kind of happens. So the spontaneity, the movement from one idea to the next — simply, one thing leads to the other. That’s how it’s been working out over the last several years, one thing leads to six other things and it is blossoming and proliferating at a rate that is very hard to keep track of. But it is quite wonderful in that regard. ¶ You were saying that you are working at a rate which is hard to keep track of. How many people are you working with? Has your staff increased with the volume of work that you have?  Franz Kamin and Felix Furtwängler, The Man Who Was Always Standing There Basically, we have me, Amber Phillips who is “production manager/publicist,” and Julie Harrison who is “artist-in-residence/designer.” These are the in-house people. Beyond this are freelance people that we hire — designers, printers, binders, copy editors, proof readers — we also occasionally have interns who come from various colleges and universities. They stay for a while and have an input. I am very interested in each project having its own life and its own identity, its own feel, its own look. I’ve never wanted to have a house style per se, I’ve never wanted to do books in a series where everything looks the same and is in a regular format. I am much more interested in working with people who bring their own design sense to a project, so that the whole project ends up looking like them and not like something that was done at Granary Books. I think that there are some unifying elements among the various books that I have published, but I hope that the surface character of the way that they look is not the primary one. ¶ To go back to your publishing debut, I was wondering who your publishing mentors have been? Could you tell us more about The Jargon Society, Something Else Press, and Coracle Press? How did those presses influence you? How did they shape your literary tastes and publishing line? What principles did you learn from them? That’s a big question; obviously it’s had huge repercussions. It’s been twenty-some years since those influences were first encountered and they still seem vivid — they are deep wells, veins of pure gold to be mined forever, I guess. |

Franz Kamin and Felix Furtwängler, The Man Who Was Always Standing There |

|

I connected more with the Press as a writers’ press than as a press that was a press first; and I think a lot of publishers that Granary was then distributing were presses first, they were exercises in printing and bookmaking more than in publishing. That’s a loaded statement and I don’t entirely agree with it because I don’t mean to put anyone down, but I think that there is some element of truth in what I am saying. The poets that were most important to me as a young writer and as a young publisher were all showing up (or had already shown up) in the Jargon Society: Lorine Niedecker, Charles Olson, Mina Loy, Robert Creeley, Joel Oppenheimer, so many others — writers and their books, that just carried me away. ¶ Are they still in existence? I seem to remember that the Jargon Society is, but I am not sure. Actually they are — the Jargon Society and Coracle are both still quite active. Dick Higgins’s Something Else Press ended in 1974. ¶ You publish a lot of art books and a lot of collaborations between poets, writers and artists: how do those limited editions fit in the general publishing activity and economy of the house? Do you place yourself in the tradition of what Jerome Rothenberg calls “the poet-&-artist driven publications” which proliferated before and after WWI in Europe and in the tradition of poetry magazines and publishing houses that existed in the U.S. from the 1960’s to the 1980’s? For me, it’s the project itself which is self-defining and the influences are best identified after the fact. I mean, there are influences and I am certainly aware of them and I do not mean to say that the ideas driving Granary are new by any means, but I think that the totality of the tradition and of the roots, the backward-looking of it all, is really known, perhaps better, by someone other than myself, because it is not a conscious decision to emulate something that has come before, although of course that is inevitable. ¶ If we take the idea of collaboration, it seems to be taken to its fullest: in what way is the idea of collaboration not being taken for granted, for something static, a mere juxtaposition between writing and images? Is not the very term “collaboration” explored by the books you publish? In what sense is it explored, challenged and rejuvenated/constantly redefined? I don’t mean to sound naive but there is kind of a simpleness that is driving things — particular projects are not coming out of a specific programmatic approach to investigating ideas such as collaboration, it is really much more about doing what seems interesting or exciting or like the way that everyone involved wants to do it. It’s something I try to nudge out from the books themselves, what it is they’re going to be, without putting too much emphasis on that. And I do not mean that in any kind of mystical sense, but simply in the sense of several people working together who are coming into it with the idea that they’re working together. |

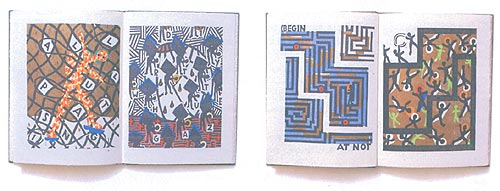

from Ric Haynes, Rejected from Mars (detail) |

|

Some people do not like to collaborate, they really like a more clearly defined set of boundaries. I’ll give you two examples: one is The Lake. It is a collaboration between Lyn Hejinian and Emilie Clark and it truly is a collaboration in that each person was involved in writing, in selecting the writing, in the placement of the writing on the page and each person was also involved in the picture making. Now, Emilie is really the visual artist and Lyn is really the poet, but when they came together to do this project, they basically developed the overall vocabulary of materials that they were going to use and then they worked together to make the piece. This came out of a four-year history of working together — they took a leap, they wanted to put themselves into a situation where they were in unknown territory, this was a conscious choice. ¶ You have published Edmond Jabès [translated by Rosmarie Waldrop]: what drew you to Jabès? Is it something that you initiated or is it something that you talked about with Rosmarie? What interested me about Jabès was his lifelong discourse about the book and writing in a way that was completely fascinating to me, if not difficult to re-state in my own words. I felt that he was grappling with and exposing and making me aware of aspects of the book and writing that were very tantalizing, in a language that was powerful and evocative and serious. I invited Rosmarie to do something of some sort and asked, “what’s left of Jabès to translate?” That’s how it came about. She chose to work with Ed Epping on that project, she had seen the book that Kimberly Lyons and Ed Epping had done called Mettle and she very much liked his work. So, in the case of that project, Rosmarie did the translation, and from then on, it was given over to Ed who designed it, created the digital images, and who basically put the whole thing together in terms of the look and feel of it, its spare character. ¶ Speaking of Ed Epping and Kimberly Lyons, since we are translating her work: how did you get interested in her poetry? I’ve known Kim for about twelve or thirteen years, I like her work a lot and I felt that she was not published enough, and I wanted to try to do something about that [by publishing Mettle]. But you see, [Mettle] was a small limited-edition, so I did a regular trade book afterwards. ¶ That’s her Abracadabra... Yes. ¶ And that was published in January 2000 Yes, just a stroke after midnight, January 1, 2000. ¶ Speaking of Abracadabra, I would like to focus on Charles Bernstein’s expression “the magics of bookmaking.” In his introduction to When will the book be done?, he finds a particularly relevant synonym to the verb “to publish.” He says that Granary books were “conjured” by you. What do you make of that? Do you see yourself/the publisher as a magician, a conjurer? and yet avoiding an all too easy mysticism... Well, a descriptive phrase I like was first coined by Daniel Kelm: that of “midwife,” because there’s a direct involvement, but with a light touch, that is to say, we’re trying to get something to happen that really needs to have its own life and my job is a kind of facilitator, nurturer in a sense. So there is a little of that conjuring, but what it is I’m conjuring, I do not often know and that is what keeps it interesting and exciting. Curiosity drives a lot of the projects, that and a trust in the process of an artist’s or writer’s work. For example, inviting Anne Waldman to do a book without any sense of who she might want to work with, and then trusting her to come up with someone that would be of interest, and then just nurturing the whole process. ¶ Once the “bookmaking process” is no longer thought of as a means towards an end but as the very process that will shape or give birth to the book, does not the traditional and simplistic opposition between contents and form become irrelevant? You quote Robert Creeley and his line as one of your principles... “Form is never more than the extension of content.” Well, it’s a recognition that form and content, in a sense, are the same thing or that they can be the same thing or that they might try to be the same thing, or somehow that they are very intimately related (laughs) — if it’s done right. Possibly there is no wrong way to do it. On the other hand, if you’re John Cage, possibly there’s no wrong way to make an art work, all ways are the right ways. It’s not a literal attempt to give physical form to what somebody might perceive to be the meaning of this writing, it’s just to give it some form, whatever that form might be. Maybe there are an infinite number of forms, but once a form is given, it’s set and done, no matter what all the micro decisions were that went into making it — deciding this paper, not that paper, this binding, not that binding, this color ink, this type face, this picture, this size, all those millions of decisions, and then the thing is done, and that’s it. So you recognize that form and content are the same thing at this point. ¶ You not only publish collaborations between artists but also “a set of essential scholarly texts about the field of activity of which Granary is a leading exponent” (Charles Bernstein). Is it not as if, what you are doing at the level of the book with the bookmaking process being first and foremost, you also do at the broader level of the publishing house with the reflection on publishing becoming part of the publishing enterprise? How does the reflexivity of the act of publishing help you steer your publishing house, how does it tie in with the rest of the books you publish? I don’t know how to answer that. I mean, there is a clear interest in publishing — in producing, in making, in writing, in the reflection on all of these things, in the history and the future of them as well — that operates on the level of simple documentation, from a sort of physical description of an activity in that world — for example, A Secret Location on the Lower East Side — to a more anthropological, philosophical, spiritual, metaphorical approach, as is seen in the companion volumes, The Book, Spiritual Instrument and A Book of the Book. ¶ That’s what I was going to ask you: “taking formal self-reflection about books as a fundamental part of its project, Granary has arrived at a richly dialectical form of publishing” (Charles Bernstein p. 8): how do the philosophy and theory of publishing (let’s not be afraid of words here) and the act of publishing interact/ interplay? One thing leads to the next, literally. The first trade book — and maybe there would not have been more had there not been the need to do The Century of Artists’ Books — in a sense, when it was done it was seen as a one off, just a needed book: “this needs to exist so let’s do it, I know I can find an audience for this book because it’s needed and it will also support the activity not only of Granary but of many other people who are working with artists books, in and around artists books.” But when that book came out, it was a very evocative book — it’s a big subject, it implies so much, it asks a lot of questions, and begs for further considerations, further discussion, more books, more talk. ¶ You seem to have a particular fondness and devotion to the book as Art object; to the book not only as words on a page but as a three-dimensional object; a particular attention to form, to contents and to the process of making the book. Could you tell us more about that? Could you tell us where that attention comes from when some publishers pride themselves in just caring about contents and nothing else or when some publishers (usually corporate publishers) put out paperback books which just fall apart after you open them three times? Could you tell us what that attention implies in terms of publishing line, of politics and economics? |

from Aaron Fischer, Ted Berrigan: An Annotated Checklist |

|

There are two things: first, there is the purely physical sense of wanting to do things well, you know, well produced, so that it stays around and has some life — it’s made out of durable materials and functions well for what it’s intended. Second, and I think importantly, there is a desire to work among writers and artists who see all elements of the book as being important, who invest meaning or semantic character or quality into all aspects of the book — they take into consideration all these things. At that point, the physicality of the book has value beyond simply one of durability and a longer shelf life. These are all considerations toward the total work of art that is being made. ¶ Which makes me think of a point that Charles Bernstein makes when he mentions the defiance of some of his friends towards small limited editions when there is an overall concern of getting the work “out there,” as they say. However, he adds that since Granary publishes all types of books, limited editions of collaborations between artists and poets also provide “alternatives to the standard formats of mass reproduction.” I was wondering if Granary Books was not a successful attempt at having one’s cake and eating it, or having one’s book and reading it? Why, certainly! And Jonathan Williams said it best — that he wanted to produce the books that he wanted for his own bookshelf. And that is a concern, just thinking about that argument, the idea of getting the work out there vs. producing a book that clearly is not going to get out there, that is going to have a small audience. I think, as Charles pointed out, for himself in any case, he has plenty of books available: having this one poem in this [limited] form is not really depriving the world of writing by Charles Bernstein. So in these few instances maybe it’s more interesting to take some time and to linger with all the possibilities. ¶ There was one thing I was interested in: this idea of “alternatives.” In his introduction, Bernstein mentions the idea that form and typography do not determine contents in a sort of unsubtle and causal way; rather, form, typography, format are and cannot be separated from contents, they cannot be considered as a mere trifle: in other words, one cannot be oblivious to form or format for it is when they disappear or are taken for granted or become almost natural that we’re in for trouble. Charles Bernstein says: “Granary Books insists — in words and deeds — that the dominant formats, including the conventions of standard typography, layout and page dimension, may restrict meaning as much as facilitate its transmission” (p.9). I guess my question then would be: how do you go from “restricting” to making sure it “facilitates” the transmission of knowledge/meaning. How can you make sure that a given format facilitates transmission, how can you try and make sure that dominant format and book conventions are not taken for granted and do not serve as means to water down and restrict meaning? I don’t think you can, I think that is part of the risk involved, you really do not know until it’s over, or even until some time later, whether or not it’s been successful. You can usually spot the failures quite easily when they are sort of overdone or overdesigned, like Wired magazine for example. The proliferation of desktop publishing equipment has certainly made the reality of publishing more available to more people than ever before, so you do see a lot of over-production, over-design, over-kill, because there are too many choices. I think there is every reason to be concerned because you don’t know, you find out later. ¶ Do you not think that being an independent publisher today in America is somewhat of a heroic act, what with the corporate nature of the publishing world, the poor distribution and the demise of independent book shops replaced by pseudo-literary supermarkets such as Barnes and Noble? Jerome Rothenberg in his introduction to A Secret Location on the Lower East Side starts out with the notion of margins. What is your relationship to the margins, how do you conceive the links between poetry, your publishing activities and the idea of margins? It’s in the margins: the writing itself, the making of the books, the publishing, and the distributing is in the margins. The economics of it is one of the marginalizing factors. How do you do it? How do you pay for it? How can you possibly pay to produce those books that basically have an audience of a few hundred or few thousand people at best, in a context of corporate distribution, where these kind of books — serious literary books or art books — don’t really have the specific appeal that is going to win them a visible spot in Barnes and Noble? Even if they had it, I don’t think it would help, the content is still the stumbling block, it’s difficult material, it is not going to have a wider audience, regardless of price or availability. I don’t think that’s what’s standing in the way. ¶ So what’s standing in the way? It may be a preconception of how history develops but do you think it is more and more difficult to publish the books that you are interested in? Well, I think what’s difficult is getting any attention for doing it, for selling the books or putting them into the mainstream process of distribution, with sales reps, book buyers and all that — that’s the hard part. The making of the book and getting it ready for its public debut, in a sense, that’s the easy part. Then, once you get there, the whole mechanism falls down because there is no place in our society for — and it is a cliché at this point — there is simply no economically viable place for this kind of writing. It’s just not there and it probably never will be. ¶ I was told that about twenty years ago New York had a lot of book shops. If you want to find Granary books you can go to Saint Mark’s bookshop, I guess, or to a few other book shops. Do you think the places where you can find the books are fewer? For the regular books, they are as available as they’re going to be, given what they are, given that there are seldom reviews in mainstream publications. One can not really expect a bookstore to carry them if there is so little support for the possibility of the book actually being sold. So, it’s a discussion in which I find no satisfactory ending. I think that on one hand, the internet has leveled things so that now everything is available if you want it, if you know about it and want it, you can get it, you don’t need to rely on there being books in independent bookstores — it would be great if there were because you want to hold the thing and see it and look at it. I know people who won’t buy books on the internet for that reason, they want the whole experience of stumbling upon something, or the chance encounter — but if I want a book and I know what it is, I’ll just go online and get it. ¶ Your distributor is DAP right? DAP is mainly art right? Yes, they focus on art, photography, architecture and fashion and I went to them initially because I knew the woman who ran it, and the first book that I had was The Century of Artists’ Books and it seemed to fit in their domain. I had not really planned on doing anything else, so I really needed a distributor to do one book, and now that one book has grown into thirty or forty in-print books. I also use Small Press Distribution; they have all the poetry books. ¶ Do you have any specific links with bookshops? Granary was first a bookshop if I am not mistaken. For a number of years, Granary was based in Soho and was a gallery. There was a period of time when it did resemble a kind of a bookshop, and then for several years, it resembled mainly an art gallery and it was concerned with exhibiting books as art, and then I stopped doing exhibits altogether and concentrated on publishing. There are no specific connections to bookstores at all. ¶ It is said somewhere in A Secret Location on the Lower East Side that “at least for a short while, trade publishers in New York and elsewhere did take considerable interest in the new writing” (p.41). In what ways has it changed? Are trade publishers no longer interested in new writing at all? Tom Clark told me his explanation for the flash of interest among trade publishers in the more experimental or uncommon kinds of writings was much more a fact of the sixties, it was just a flash, there was not really a deep interest, it was “maybe this will catch on, maybe not” and that was it, they let it go very quickly. What’s happened in its place is that certain of the more interesting small presses really grew up and became larger, more established, presses with major distribution: New Directions, City Lights, Black Sparrow, or Sun and Moon, for example. So, if someone wants to be more ambitious it is possible to get the books distributed if you want to make them look like regular books, and so forth — that was one of the ideas that was motivating Something Else Press. Dick Higgins was devoted to the idea of making the avant-garde widely accessible, and so, he made books that looked like normal books, he had sales reps, he had distribution, he would attend book fairs, he was trying to act like a regular trade publisher. The result of that activity is this: he achieved a certain degree of success, his books are available in small libraries all over the United States, they’re everywhere, he really did get the books out there. He had the energy to do it and he had the entrepreneurial sense, which is something that I think is a factor, a considerable factor, in the success or failure of a small press. ¶ I think I’ll end with your website. Your website is amazing and gives a good insight into your publishing house, you have even posted online collaborations between poets and artists. What do you think of the internet and of the e-publishing possibilities it offers? Do you think of the internet as something that is interesting as far as publishing goes? I think it is extremely interesting for many, many reasons, but I think, as a venue for publishing? I have not, as a user — as a reader — it has not appealed to me as a way to read a text or to engage in a work, in the same way that interactive CD-ROMs have not engaged me in that sense. I do not find myself using that medium, so I certainly do not see it as anything I am interested in pursuing as a place to publish. It is a great place to get a taste of something and to be drawn back towards the physicality, the human character of the work. I certainly do not perceive it as a threat because the whole existence of the enterprise is constantly threatened far closer to home! It certainly is not a way to sell work either. It is like an elaborate catalogue, it is a way to make information available and I think that probably, indirectly, it supports a lot of activity. ¶ Do you sell a lot of books? The company is entirely self-supporting, we’re not a non-profit organization, there is no outside patronage per se, there is no family money, so it really is self-generating and moving forward through its own energy and economic fuel; we just find a way to keep making it happen, one project to the next. The limited-edition books can be lucrative. I also deal in archives and manuscripts, which helps to support our activities. I do really see it as an organic whole, I think the scholarly books and the histories and so forth support a broad awareness of the total activity in the field, not just of the total act of literacy, of thinking, of reading, of writing. Actually, I feel very hopeful that there is a continuing with books, I do not feel that we are at the end of a process (although we may very well be) but I certainly do not see it that way at all. I feel more hopeful, more inspired, more energized, more curious each day with each new project. ¶ Thank you Steve for your time. |

|

Thanks to Double Change magazine at http://www.doublechange.com/, where this interview first appeared. Double Change is a web journal dedicated to French-American interaction in poetry; its first issue was published in mid-2001. |

|

Jacket 15 — December 2001 Contents page This material is copyright © Olivier Brossard and Steven Clay and Jacket magazine 2001 |