|

But I didn’t really care about any of that. I admired Carnegie for his nickname “King of the Vulcans,” as well as for his rise from the factories. I went to the library every day to pore over the books, and took many home to read under blankets with a flashlight, concealing my interest from my father, only barely more tolerant of books than he was of art.

I found Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass on a shelf sagging with the 19th Century American poetical tonnage of (to name an illustrious few) Edgar Fawcett, Richard Watson Gilder, Charles Fenno Hoffman, Emma Lazarus, Sidney Lanier, Celia Thaxter, and Cincinnatus Hiner Miller (better known as Joaquin Miller, a Whitman impersonator), Parnassian giants all, for the sake of whose yodeling countless acres of virgin forest had been pulped. Whitman was held upright by dog-eared volumes of Elizabeth Stuart Phelps Ward (renowned), and John Greenleaf Whittier (a voice humanely silenced “by the breeze, moaning through the graveyard trees” of his productions).

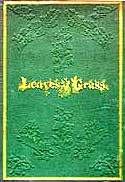

There were other editions of Whitman’s book, but I recall pulling out the thinnest, the first edition, or a facsimile of it. It was probably the size that drew me (less than a hundred pages and tall like a picture book), as well as its striking design. It was green with a gold title, roots sprouting from the bottoms of the letters, leaves flowering from the tops, and the back cover was identical when you flipped the book over, implying the beginning and end were the same, or that there was no beginning or end, or that everything was somehow upside down. There was no author’s name on the cover (though copyrighted inside by one Walter Whitman in tiny letters), but opposite the title page, was an engraved daguerreotype of a man who looked like a cowboy: hat, no suit, no tie, no flowing hair, no pencil poised like a dart, and no Victorian look of smug transcendence or self-indulgence.

I knew it was poetry because of where it was located in the library, but it had a wonderful absence of the tin-eared rhyming nailed into my head in English class. Thumbing through it, I thought it was some sort of mis-shelved bible because of the language, until I read the introduction, which told me the genius of America was its “common people,” for which I read “working class poor.” I believed it immediately and imagined the president doffing his hat to me at the construction site where I worked demolition on weekends, or at the Five & Ten where I washed dishes weekday afternoons, asking my advice on everything from the price of beans to pending wars, especially the one my friends and I were destined to be involved in — each working class generation had its own war, and we were waiting for ours.

The force of my experience with Whitman’s introduction paled once I read the first poem, the untitled, unnumbered blasts of language and thought which in later editions would be tamed into numbered sections with the misleading title “Song of Myself.” It was Whitman at his purest, untainted by later affectations and delusions of grandeur — a profound masterpiece resulting from some sort of pre-Civil War satori experience without the benefit of Buddhism or LSD. I didn’t really know what he was talking about, but I couldn’t put it down. The moment I picked it up, Leaves of Grass ignited in my hands. It expressed a view of the universe that was as like and unlike Pittsburgh as possible, and, if not cohesive or even comprehensible to me then, appeared to be all-inclusive. Its subject was not merely the world but the universe, and not only life but consideration of its opposite. The subject matter was no less than everything, or so it seemed.

In contrast to the tinkling dross that kept him company on the shelves, I was engulfed by Whitman’s vatic tone, and, unlike the others, he energetically glorified and celebrated the kind of world I lived in. I was attracted by the attention, though skeptical. Beneath the stereotypical image of the noble worker (we forthright, positive citizens who could never afford to believe official descriptions) lay the truth. Our existence was hardly a subject for celebration. It was dominated by crippling accidents, violent struggles for improved conditions, corrupt labor unions, subsistence and mortgage worries, collapsing businesses, a sliding belief in government, hatred of taxes, and a violent desire to get drunk.

But I kept reading.

Whitman seemed to view industry as a force that could carry humanity forward to higher purposes, while I constantly brushed mill ash out of my hair and teeth, fished mutant creatures from factory polluted rivers, and squinted to see the sky through gaseous mist. The working people he so revered constantly punched one another in the head, worked overtime without wages, battered their wives and children, chewed up and spit out youth and beauty with bitterness, and could never work hard enough to make enough to drink and still keep food on the table.

The sane governments, insights, and human affections Whitman intimated were not present where I lived, but he caused me to imagine there was another world, a parallel world, a shadow world of sorts, the way our labor unions were a shadow government. Perhaps in that other world, if I could find it, I would discover the source of his optimism and philosophical certainty, colored with its odd, all-embracing skepticism: “Do I contradict myself? Very well then . . . I contradict myself; I am large . . . I contain multitudes.”

But first I had to understand what he saw when he scanned the wage slave, wife beating, war-scarred motor humpers of the multi-racist working class I was part of, a world where you could be pounded with a bottle if you disagreed with someone, or smashed with a chair if you agreed. What did Whitman see? People with dreams but no money to accomplish them, I concluded, people who mistook work for freedom and poured everything into it, people who lived at the top of their lungs because they were used to being ignored, and people who lived in perpetual motion because they always had somewhere to go for someone else’s sake.

What he praised was not so much our quotidian lives as our loyal industry, unabashed directness, and our impulse to move and change. Change into what? Into anything. In that world only a fool would want to remain the same, though most had no choice but to live out static lives interrupted only by child birth, military service, layoffs, and death. Perhaps, I thought, Walt Whitman was trying to drum up compassion for our world, while trying to lift our spirits and encourage us to break loose — it struck me that way, and there was no one around to argue otherwise. For all I knew, his work represented the sort of political bombast my father was fond of pointing out, but I didn’t want it to be so, and luckily it wasn’t. Like any other adolescent, I cautiously wanted something pure to believe in, and while baseball and basketball won over many of my friends, I went for Whitman.

I never discovered the source of his optimism, but eventually, despite a lack of critical ability and historical understanding, began to appreciate his work for its sheer exuberance and energy, its resistance to conservative logic, and its almost total absence of Victorian prosody. It was his ineffable reality I came to accept most deeply, not his meaning, and certainly not what I initially misinterpreted as simple nationalism, though that was certainly part of it. It was poetry as powerful force of observation, mysterious vision, and insight, no matter how impossibly hopeful.

By extolling the virtues of human experience with such ostensible ease and unabashed ecstasy, he was, I thought, in a way inviting everyone to be a poet or an artist, to free books from their libraries, paintings from their museums, and to pry everything creative away from professionalism. The farther from institutions, the better, the more distance between art and hallowed halls, the more likely it was to evolve, or, at minimum, change importantly.

As it happens, North American poetry has emerged since his time as the most inclusive and malleable of arts, though not because it is plastic, but because from it the least is expected. It cannot be traded as commodity because it has no physical value, and cannot specifically belong to anyone — its virtue and curse. It cannot be defended from pretenders because it has no gate to guard, no public expectations exist for it, very few people read it seriously unless they intend to write it (or already do), and no one can defend its higher qualities comprehensively because none can agree upon what they are. In fact, no one understands exactly what it is, and it is protected from legislative censorship not by its failure to provoke consensus or dissent, but by the reality that most US politicians do not (or simply cannot) read it, including recent presidents.

One must, however, note an exception to that generalization, considering that Whitman’s Leaves of Grass was drawn, along with cigar dildos, into the late twentieth century President Clinton-Intern Lewinsky debacle by virtue of the fact that the book was given as a gift by the sax blowing commander in chief to his kneeling beloved at the outset of their trysts. Until that information surfaced, Whitman had not been involved in a government scandal (albeit on a lesser level) since being fired from his job at the Bureau of Indian Affairs in 1865 by secretary of the interior James Harlan just after the Abraham Lincoln assassination. Harlan, a conservative, considered Leaves of Grass obscene, though he later denied that was the reason he fired Whitman, which makes him a liar as well as a government censor, neither of which is rare. The more recent Whitman sighting is humorous, somewhat thrilling if one considers the romantic nature of the gesture, and, if anything, illustrates that Clinton did indeed have something in common with Lincoln: they both seemed to like Whitman, though there’s no evidence that either actually read him.

For aspiring poets, there’s still an important lesson to be learned from Whitman the artist, and the earlier the better (those already cynical and putrefied may relearn it if they wish): he was not doing a job. Poetry was not his profession, it was his life, a necessity, pure love, and when he wrote “I, me, my,” he wasn’t writing to draw attention to a suffering, unattended ego. He was reaching beyond the self, out into the living universe of things, ideas, and events — the world he was part of — as if through poetry the universe could rise up with a human voice.

In his case, it could. But in the end, I think he was mistaken (however ecstatically) about the realities of the working class, the common people, though his roots were those of a working man and commoner. He wanted their world to be something it never was, and transformed it into a platform from which to project idealized perceptions and imagined possibilities for a flawless democratic society, something quite impossible. Then again, the poet who would come to write one of the most moving of Civil War memoirs (embedded in his autobiography Specimen Days) could not foresee, or chose to ignore, the carnage poised to emerge from the intrinsic flaws of the virtuous society he extolled and glorified in that first masterpiece, “Song of Myself.”

Hindsight may not be to the point, and his world lacked the mass communication syndicates that inform us of the most minuscule news items and social developments, but one must question how it could be that a man who lived with his eyes and heart wide open, could have so little to say about certain matters that truly contradicted his notions of liberty and freedom. He was, for example, sympathetic, but not very mindful of slavery, and was certainly not an abolitionist. Nor was he particularly attentive to the past and pending genocide wrought against native Americans by the original Euro-invasion and on-going US westward expansion, in spite of his employment at the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

In his work, there are no songs of labor about the severely abused transcontinental railroad and Gold Rush Chinese, no mellifluous observations of gandy dancing Irish pounding their brains out on the tracks, no Latinos to speak of, and only a passing mention of Jews. His was not an empty country (what we see now by way of human variety also existed then), but his expanse was confined by the fact that he was mainly an arm-chair traveler. Many of the missing may be found in works like the poem “Salut au Monde!,” but from such catalogues we learn only that he knew his geography, had a vivid imagination, and was literally (merely) popping a salute from his “America” to the rest of the world, which he never saw.

For all his curiosity, he didn’t travel much. He went to New Orleans as a young man, to parts of the south and Washington, DC during the Civil War, and later in life went west by train as far as Denver. He visited Canada briefly, made it to Boston, and settled in Camden, New Jersey near Philadelphia in old age, but he never crossed an ocean, or even the Rockies (a feat for someone who lived through the great California Gold Rush and not only claimed to be manly, adventurous, healthy, and universally curious about his country, but was also a working journalist at the time). As it turns out, he was not, in fact, caught up in the turbulence and sweep of things to the degree his readers tend to believe, and his vision of the larger world bordered on the romantic and imaginary.

He adored his America, but didn’t see or experience much of it (his impressions from train windows aren’t very convincing), and his poetry suffers from the fact. He was not particularly interested in the trademark evils of the brand of democracy practiced on his home court, and there is a bruising lack of criticism in his work regarding the life crushing exploitation of the poor and working classes by the wealthy and powerful. He was our first public poet, but as observer of society at large, his poetry generally ignores the limited prospects and impoverishing conditions that faced the common people he lionized. But that’s no great surprise.

There are important exceptions (their number increases sharply mid-twentieth century), but avoiding social criticism and political content has long been endemic and symptomatic for a wide range of North American poetry, not that social indifference is confined to poetry by any means. This artistic silence (not unusually referred to as good taste) reflects a type of selective silence that flowed into our general social consciousness from the early Puritan tradition of colonial leaders never telling the British king the truth about the horrors of life in the colonies, lest he take away their power. Bad news was forbidden, and once the new Americans learned to be selective about reporting horrid social conditions, especially their disgraceful treatment of indigenous people, it became a trait to willfully ignore them, planting, perhaps, the seeds of the illiberal, intolerant conservatism that has dogged our history. In that context, it follows that even one of our most public of poets might tend to be (if not apolitical) uncritical of the country’s deepest social faults in his poetry, adding to our image of Whitman the iconoclast intimations of one flirting with conventionalism.

Still, who Whitman really was remains unclear on a number of levels. For example, which of these sexes was he: heterosexual, homosexual, bisexual, or asexual? Based on his work and biographical details, and viewed through the lens of the present, he seemed to be all four at various points, sometimes all at once, and should probably be considered — if as a sexual being at all — humanly omnisexual in order to grasp the breadth of his implications. But even in those matters, touchy if not dangerous in Victorian North America, he avoids taking a distinct position, while managing to project a sexually liberated persona throughout his work. Politically speaking, he also remains in the closet, but comes off as more limited, though it’s probably intentional.

He was very selective about his subject matter, and careful about its implications, but he absolutely believed in and promoted Democracy, which bears its own range of historical problems, leaving his work open to serious criticism. In his 1898 political essay “The Triumph of Caliban,” Nicaraguan poet Rubén Darío (Whitman’s Spanish language counterpart, and otherwise an admirer of his work), called him “a prophet of Democracy, Uncle Sam style,” meaning Uncle Sam the imperialist, unwanted invader, cultural imposer.

Claiming to be the poet of the common people, Whitman’s weakness, as I’ve been pointing out, is to have overlooked the darkest aspects of their lives in his poetry. One would not think to criticize him on that level if he had not projected his image and poetry as the voice and living body of the people en masse, but he did, and the facts of his neglect must be observed if we are to appreciate him fully, which also means considering the non-political context of most serious North American poetry. It’s not that Whitman was unaware of social problems, he was very aware of them. Among other things, he published a clumsy temperance novel (about a sot named Evans, I’m sorry to note: Franklin Evans; or The Inebriate ) thirteen years before the first edition of Leaves of Grass . But that book and a number of other didactic prose and poetry texts are so gratuitously pro-American and nationalistic in spirit that they seem disingenuous in retrospect, and he would have been dismissed as a minor pamphleteer had he written nothing else.

However, on a positive note, his overall work is too important for such a fate, and he was too impressive a figure in life to be dismissed, unless we dismiss the past completely. The seminal poet of North American literature, the best aspects of this work remain (acknowledged or not) an unshakable influence on all poetry written in English since his time.

When his poetry hit its stride in 1855 with the first edition of Leaves of Grass , it was destined to change just about everything there was to change about North American poetry, breaking linguistic, prosodic, and emotional barriers so successfully that one could no more go back to writing the sort of poetry that existed before him (not seriously at least) than one could go back to painting Rembrandts. Because of the concept and reality of time, forward progress seems actual, and as far as we know at present, nothing in the universe can return to the exact state it was in before moving forward (or in any direction we can perceive), and such is the case with all things, including poetry and other arts. Apparently, change is continuous, if not progressive, rendering Neo-movements (such as poetry’s various and recurring stabs at producing classical verse, or Neo-formalism as it is sometimes called) flat and boring unless they incorporate intentional humor or self-conscious reference to the original models.

Mixing mediums to make the point, a successfully executed sonnet today (for that matter, any classical verse form) must be at least as inventive as a Komar and Melamid painting. They are the two Soviet artists who brought us the mid-1990s Most Wanted painting series by conducting a broad, ten country survey of what average people most want and expect from art, then painted the results, which are both disturbing and entertaining. What they created are and are not paintings — they are representations of paintings. More to the point on the subject of Neo-formalism is their series of at least fifty-nine 5” X 7”, conventional looking (except for their size) romantic landscape oils attributed to a one-eyed Russian painter named Nikolai Buchomov, born near the end of the 19th Century. These paintings are part of a conceptual work, complete with a convincing photograph of Buchomov, eye patch in place, and biographical documentation, all compiled or created by the artists. The work is playful and attractive, sublime and absurd.

As pointed out by the lively art critic Arthur C. Danto, upon close examination, one comes to realize that a recurring geological detail in the paintings is actually the side of Buchomov’s nose as he gazed out with his one eye, brush in hand, at the landscape. An engaging classical sonnet written now, if possible, would have to contain self-conscious references at least that clever and subtle. We have Whitman to thank for that in part.

Since his time, North American poetry (and the rest of the world seems not far behind at this point) has experienced many deaths, mainly by university and creative writing workshop executions, and by those who insist it is a job — a crude punching of the poetry clock. It has been frozen, ossified and manipulated over and over for reasons and prizes that have nothing to do with poetry, the results of which often have nothing to do with anything significant. But it has not been buried because one moment it might be stiff upon the floor with rigor mortis, rhyming couplets dribbling from a hole in its temple, but the next it is fully awake, running around the streets with its head on fire.

It’s a duppy art. Art of the living dead.

Whitman might have added that nothing so intangible and difficult may be adequately taught at any rate, and that poetry is therefore in no danger of being taught to death. Inspiration is important, but if one is not a born genius or prodigy, the act of writing genuine poetry can only be learned, or awakened, through a life of patience, observation, omnivorous reading, and hard work. To continue doing so past middle age, it helps to view failure and success as relative, and to trick one’s good sense into thinking obscurity is the equal of fame. One must also, as Whitman did, work always without a net or concern for unfriendly opinions, and upon hitting the ground continue to plummet willingly, through everything, until gravity reverses itself and you are falling upwards again.

That may sound like hard medicine, or optimistic hyperventilation if you’re a poet on the downswing feeling dark and inconsolable, but in the United States (a now nearly post-book, post-literate society on the edge of finding out what dot commerce and the Internet will really do to the imagination, not to mention publishing, especially poetry books, which generally have a briefer shelf life than a butterfly’s existence), odds are things can only become a more intensified version of the same, until unbearable, then far worse than imagined possible. It’s best to brace oneself against the storm, though Whitman might have somehow managed to sweep even this grim reality into an optimistic poem. Then again, his accomplishments are completely native to his own time, rich as it was without airplanes, radios, televisions, computers, world wars, or atomic weapons. |