|

This is Jacket 16, March 2002 | # 16 Contents

| Homepage | Catalog |

|

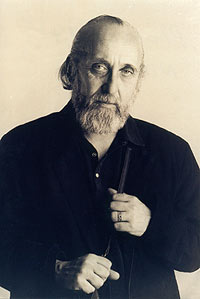

Jerome Rothenbergin Paris, in conversation with Nina Zivancevic |

One of the best contemporary American poets, the founder of Deep Image movement in poetry and father of Ethnopoetics in anthropology, has just given a reading at la Maison de la Poesie in Paris. In a spontaneous conversation Jerome Rothenberg discusses some of the major artistic and literary events that ‘shook the world’ by the end of the previous Millennium and the ways he saw them either as a participant of certain movements or a master-builder of some of them. |

|

Question: Many people have tried to define literature — what is it for you and how much does your approach differ from the traditional approach to it?

Rothenberg: My sense of literature comes basically from poetry, so I won’t broaden that to discuss various forms of fiction which would change the discussion in any number of ways... but possibly not. For me, the turning to poetry came from my need for a different kind of language from what surrounded me in the world in which I was growing up. Poetry had some of that difference, and that it was so often despised only made it that much the better. Ultimately of course the language of poetry — for myself and others — came to be closer and closer to the language that people really use in everyday speech, but different at its best from official language, from authorized language — as we get it in politics, in advertising, in standardized religion — all of that. Was there a desire also to express some sort of a ‘ surpressed ’ language, the one you spoke perhaps at home? Well, you and I both write primarily in English, though we both have roots that take us elsewhere, I’ve always written in English as far back as I’ve written and you come to the English language at a later point. But, in fact, there was the other language for me in childhood — the Yiddish spoken in my family — and certainly the first language that I spoke as a very young child was Yiddish. So I still have some memories of coming from that first language into the other language when I was maybe two or three years old. And the first language would invade the other — stray words, even somewhat later on. |

|

But then you had to suppress it in school, right?

Well, there was an obvious push toward suppression in school, but there was another push — different and maybe stronger — toward suppression in the street. So from very early on, for most of us who were immigrants — the children of immigrants — there was a movement from the place of the family into the place of the street, and the street took the part, played the part, of the larger society... I don’t know if I was compensating — later on — for the loss of the first language, and I know, looking back, that that first language was never entirely lost. I could still speak with my grandmother and the other people in my family who did not have English as a ready second language. I would speak to them in Yiddish, although over time the Yiddish weakened for me as a language. |

| |

Photo: Nina Zivancevic Have you ever tried writing something in it? Yeah, occasionaly I’ve let it come into something that I was writing, especially when I was doing something like Poland 1931. Later on in Khurbn, there are brief moments when the language invades a poem, because of what I’m doing there specifically — a response, so to speak, to two visits to Poland (1987 and 1988), with a sense of Holocaust there for the first time — the first time that I let it, that it made me let it, come into the body of a poem. Both the Holocaust and, here and there, the Yiddish. Also, many of the titles in Khurbn, including the title of the book itself, are in Yiddish. It comes in as some sort of a ‘metatext’?

Yeah, in a manner of speaking. And yet I don’t really think that it exists for me as a presence when I’m otherwise writing in English. But I do take some pleasure from time to time, on those now rare occasions when I come across an individual who really speaks Yiddish, to enter into a conversation. In those circumstances it’s always with somebody who’s a far superior speaker than I am. It’s a nice exercise in language, but not much more. You mean disturbing in ANY language?

Yes, any language would suffice. I assume anyway that something like that was going on for some number of poets, not only at the time of the Second World War, but going back far earlier than that. There were poets who were writing in French, writing in German, at both ends of the century — poets to whom this would apply. Certainly someone like Paul Celan, whom one takes as a prime example of that kind of situation — a situation in which the German language had not only failed him but was so clearly identified as the language of the oppressor. (This has been said many times about Celan, and still it’s absolutely true.) So, as his poetry, his language, develops, he builds it up of course out of German, but it’s a German that’s post-Holocaust, the German of a post-Holocaust writer and a witness. It’s fair to say that it becomes a kind of counter-German, a German that contradicts, and yet it’s all the more German for being that, the way the actual features of the parent language become exaggerated and distorted in the writing. So, would you say that the stress was primarily on the quest and investigation of a sacred language?

That too — at least for the early ones who had mystical/spiritual ambitions like their counterparts among the early abstract painters. For myself, I became aware and interested in so called ‘sacred languages’ sometime in the 1950s. At the time it was possible to think that what we were doing in the present was an ‘othering’ of language, the making of a language that, while it was rooted in the specific spoken language we grew up with, transformed that language in a variety of ways — some deeply meaningful, some not. Well, is there anything that you can find in so called ‘oral’ or tribal verse that you can’t find in contemporary poetry of today? In other words, was there something bothering you or some sort of absence in the contemporary poetry of your day that made you go back to the traditional oral verse?

Yes, but let me see how I’m going to answer that question... When I started doing books like Technicians of the Sacred and Shaking the Pumpkin what was bothering me was possibly the absence of a reason for doing what we were doing. I could explain it in the terms that I’ve been using here — a sense of the struggle between a new language and a debased older language — but what struck me most about the old poetries was a resemblance to what the experimental poets of our own time were doing, but at the same time rooted in tradition — a poetry in which, even when one departed from obvious meaning, so to speak, into what the anthropolgists and ethnomusicologists used to call the ‘nonsense’ syllables, the resultant work — the poetry — was deeply deeply involved with meaning, and furthermore the poetry seemed to exist at the very center of the culture from which it came. I think that every honest writer feels, at one point of his development or another, that connection with the previous tradition, as he also feels dread that what he has said is not new but an echo of the previous school...

Oh, that also, but of course at other times I obviously felt a great excitement that everything that we discovered might be said to have been discovered previously: forms of experience coming into contemporary poetry, contemporary writing, contemporary art... voices omitted from previous discourse... compressed identities... body and mind... a vast amount of dreamwork... visions of gods and men... and women. What is your stance on deconstruction of poetic language, on ‘language poetry’ that became predominant in the last decades of the 20th century — have you participated in that movement, or do you consider yourself a participant in it?

Well, language poetry — to which I had some closeness and some affinities since its beginnings in I guess the 1970s — represents a particular self-defined movement by certain poets who recognized themselves as sharing an approach to poetry that was setting them apart. To me it seemed after a period marked by a poetry that either in a shallow or a profound way explored personal experience, that with poets like Bernstein and Silliman and Andrews and others, there was a return to an exploration of language... of words and the way words came together... of meaning and its problematics. There was a concern with things that were concerning others of us also but that we had failed to nail down in a way that called sufficient attention to itself. [A move from experience back to language, which I thought was very salutary then, but neither side sufficient in itself.] Well, I don’t know if you’d agree on this, but Charles’s case is very specific — because he combines this oneiric, dreamlike quality...

Oh, increasingly... but I’m really trying to think back to the mid-70s situation. I had done a little publishing with Ron Silliman when he had a first magazine called Tottel’s Miscellany, and, although it didn’t fit directly into the language poetry grouping, with a magazine of similar interests, ‘Zero to 9,’ which was published by Vito Acconci and Bernadette Meyer. For me it was all a part of our activity at that time, and so I found myself curiously in the position of bringing Charles Bernstein and Bruce Andrews into that framework, although they would have made their way into it anyway. It was just that I happened to be there and told Charles and Bruce, separately, to get in touch with Ron Silliman because the poems that they were showing me seemed to be close to the kind of thing that Ron and the people in San Francisco were exploring. It is funny though — the other day I was reading your old interviews and there was your dialogue with William Spanos where you tried to avoid this academic kind of vocabulary and he was insisting on it...and it was funny also when Armand (Schwerner) said that he wanted to step away from them, from the language school, and on the other hand many language poets claimed him to be one of their grandfathers or predecessors...

Yes, but I think in Armand’s case — because I had conversations with him about all of this — he felt himself not sufficiently recognized by the younger language poets. There was a degree of tension for him around that, but for myself, I had come to them at a different point, and there are certain personal associations, it seems to me, that very much influence how one thinks of the work of others. It is hard to talk about movements of any sort in art and in literature- there are so many of them, and their branches as well!

Yeah, but it [language poetry] was as much of a movement as we had that point — in American poetry at least — and it did cause a shift away, for better or worse, from a lot of the emphases of the immediately preceding generation. Still, there were many things of value — certainly for me — in the poets of my own generation or the poets who were somewhat older: the historicizing of Olson, the history plus mythopoesis of both Olson and Duncan, all of that was important; the experiential work at its extremes, not the confessionals (so-called) but what Ginsberg or, from a different perspective, Eshleman were capable of doing. You’ve been devoting a lot of time to the editing of anthologies, the most recent one being Poems for the Millennium. When compiling them, were you guided by criteria such as different literary movements, chronology, or some other ones?

Well, when you say ‘movements,’ there is no question that with the first volume of Poems for the Millennium, one of the objectives that Pierre Joris and I had in mind was to give particular attention to certain of the major movements of the early part of the twentieth century. This followed from our sense that particularly in the United States there had been an overlooking or a downplaying or a scorning of those movements when it came to poetry, and we wanted to put the movements back into the history of poetry. (They were of course well enough known in the history of art.) That’s a different approach to editing, say different from your earlier work exemplified by the anthology Revolution of the Word. I remember reading it aloud to some people and every poem in it was a specific individual expression of a certain craftsmanship.

Revolution of the Word was a small anthology of American experimental modernism in the twenty-year period between the two world wars. That was something different and did in fact concentrate on individual poets. But in Poems for the Millennium also, most of the poetry does not appear within the movements but in those other sections to which, as curators of the book, we gave the term ‘galleries.’ So there are three galleries of individual poets, and then a section at the end of ethnopoetic sources and writings, both from the traditional cultures as rediscovered in our own time and from twentieth-century writers showing the influence of other, either non-western traditions or occulted European traditions... Was there something that occured in your research of the traditional verse that led you straight to the avant-garde of the 20th century in poetry, or was it your research of the 20th century poetry that took you back to the ancient verse?

Well, I think I would look back for myself to the 1950s — that there was an opportunity to go over again the history of what had happened just before our time, partly because it was a very conservative time in American writing or certainly in American poetry, and the experiments of the early part of the century were said to have been bypassed by then. This was a dead letter, this was not something to work with any more. And that gave us an opportunity to look back and say: is this really a dead letter or are we being told that by those whose work in fact is deader than a doornail? When would you say, this shift started in American poetry, these changes which you have just mentioned?

Well, I think much of this had been brewing for a long time and had never really disappeared, although for some of the poets who had continued to practice a more structurally or a more experientially experimental modernism, there were some very dark and neglected years. Poets who became important later to some of us — like Oppen, Zukofsky, Reznikoff, who were the then forgotten ‘Objectivists’ — had never come into high recognition during their early years, and for a period of time — from the middle 1930s until their rediscovery by my generation in the 1950s — they had been, as someone in my family used to say, talking to the wall. They were writers without recognition, without an audience, and because of their work and their courage (if I can say so) they became very exemplary figures for us later on. Given the fact that the realm of the poetry perfomance is still being discussed here in Europe as some form of a slippery ground, that is, people are still suspicious of it, could you clarify here what importance (if any) you give to gesture, movement, dance in your own poetic events? Like the event we witnessed last night — I call it ‘event’ because you read your poetry which was obviously written on the page, but still, there was more to it...We know that poets don’t have scores to read to, so, how do you get to read your musical work?

Well, some poets of course do have scores, going back to Mallarmé’s Coup de Dès or Schwitters’ Ur Sonata, and forward to post-World War Two sound poets and others. Jackson Mac Low, in many of his poems, writes with scores that are notated for such normally musical considerations as speed, loudness, duration, duration of silence... numbers of other things that come into his scoring. Other American poets, certainly from the time of Olson on, began to look at the disposition of words on the page as being a key to how the poems were to be read aloud in a performance situation. So that book called What It Means To Be Avant-Garde was actually taped and transcribed?

Yeah, David’s method was to talk, simultaneously to tape, to transcribe the tape, and to whatever degree he chose, to rewrite it in the process of making the final work. So it’s not like somebody else... not like the old Andy Warhol book which is just talk talk talk talk, with the uhs and the ahs and mmms... everything transcribed exactly as it was spoken. No, David will depart from that and work over the transcription when he does it in written form. This question almost imposes itself on us now: if we had an imaginary library of all your work — your books, and then the same work on CDs or CD ROMs — would readers treat them all as different works (those in books and their ‘replicas’ on the tape)?

I think for many readers of the work they would get a different sense of it once it was accompanied by my voice reading it, as people get a lot of information about the nature of the poetry when I do a live poetry reading and as I get information about the work when I hear other poets whom I’ve only known on the page in written form do a live poetry reading. Once I’ve heard them read their work, even if they’re not such good readers, it teaches me a lot about the nature of that work that I would not have known otherwise, because the score is not a clear score... because we’re not really systematizing in that way. |

|

Nina Zivancevic is a poet, fiction writer and a scholar-translator who resides between New York and Paris. But her main home remains the hidden ‘house of language’, as Heidegger would have it. Andrei Codrescu said of her ‘Among us bilingual guerrillas, she is the chief flame-maker.’ Charles Simic claims that she is ‘one of the most interesting and original poets in Eastern Europe’ who taught herself a highly idiomatic American by writing original poetry in it. |

|

Jacket 16 — March 2002

Contents page This material is copyright © Jerome Rothenberg and Nina Zivancevic

and Jacket magazine 2002 |