|

Jacket 17 — June 2002 | # 17 Contents | Homepage | Catalog | |

Catherine DalyMarjorie Allen Seiffert and the Spectra HoaxThis piece is 2,500 words or about five printed pages long |

|

When Witter Bynner decided to write hoax poetry in 1916, he thought he would found an entire hoax school called Spectra. The Spectrists would join the imagists, vorticists, and other groups, but satirize them. He first invited Arthur Davison Ficke, a friend of Bynner’s from Harvard undergraduate days. Ficke was a lawyer based in Davenport, Iowa, who spent an extensive amount of time in Chicago with the Poetry crowd. Ficke had published collaborative work before: a long piece Ficke wrote with Mary Aldis called ‘Chloroform’ was published in The Little Review in 1914, and then republished in Aldis’s book Flashlights in 1916. Together, Bynner and Ficke published a small pamphlet called ‘Spectra,’ but realized that with only two poets, the movement was too small. They quickly invited a third poet, Marjorie Allen Seiffert, a wealthy matron in Moline, Illinois, who had experience publishing hoax poems at The New Yorker under the name ‘Angela Cypher,’ to join them. |

| |

|

A.D.Ficke, 1940, photograph by Carl Van Vechten |

|

As Emanuel Morgan, Anne Knish, and Elijah Hay, Bynner, Ficke, and Seiffert wrote and circulated a manifesto, submitted and published poems in the leading journals of the day, including Others, Poetry, and The Little Review, and engaged in correspondence with literary luminaries of the time. William Carlos Williams ‘wrote to Marjorie Seiffert (as Elijah Hay) complaining that he preferred the work of Morgan and Hay to that of Knish [Ficke] because “she” took the Spectrist affair too seriously.’[1] Actually, Williams wrote, ‘The woman as usual gets all the theory and — as usual — takes it seriously whereas the male knows it’s only a joke — serious as it is. A.K.’s things suffer from too much theory.’[2] |

|

When Marjorie Allen Seiffert published her first volume of poems, A Woman of Thirty (title based on a Balzac novel), she reported to Margaret Anderson that it was financed by her father, after an argument over its content,[3]but in fact the volume was published by reputable publisher Alfred Knopf in 1919, long after Seiffert’s marriage. This father-financing story is important to note. Although an independently wealthy person with a coterie of very well-published poets as friends, Seiffert’s relationships to family and community were undermined by publication. Her wealth reinforced non-publication and pseudonymous publication which had been a more common experience of women of the previous generations, since her family sought to preserve the status quo by limiting female accomplishment to the family circle. She included a section of Elijah Hay poems in her first volume, republished here. |

| |

Marjorie Allen Seiffert |

|

Marjorie Allen Seiffert’s contribution to the hoax has until now been reduced. William Jay Smith first published the book The Spectra Hoax in 1961, seven years before he became Special Consultant to the Librarian of Congress (before the holder of that post was referred to as ‘Poet Laureate’ of the United States). In 2000, the book was re-issued by Story Line Press. Smith mentions — and pictures — Marjorie Allen Sieffert / Elijah Hay in his book, but only republishes two of Seiffert’s Hay poems, one an unpublished one from a letter to Bynner in 1917. By contrast, he includes the ‘Spectra’ pamphlet of Ficke’s and Bynner’s poems in its entirety as well as a further sample of sixteen Bynner poems. He also includes two poems by George Sterling which were not deemed ‘spectrist’ enough to include in the hoax. |

| |

|

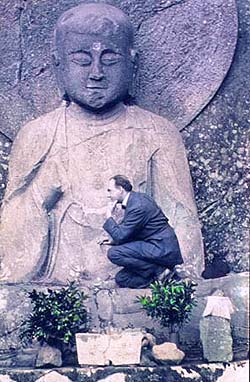

Witter Bynner posing before a shrine in Japan. Hakone, 1917. |

|

The reduction of Seiffert’s role is not surprising. ‘Spectra’ only featured work by Bynner as Morgan and Ficke as Knish. The letter-writing campaign and periodical publication included all three; Seiffert was the only participant to publish the poems in a volume with poems she wrote as herself. After the hoax was revealed, Bynner continued to write and publish free verse — whole volumes of it, and for decades — under the name ‘Emanuel Morgan,’ although readers knew Morgan was Bynner. Smith’s main informant was Witter Bynner, who also sought to keep the hoax alive by having his assistant compile a complete Spectra ‘sourcebook,’ and, apparently, talking about the hoax at dinner parties.[4] |

|

Poems of Elijah Hay The Golden Stag

O hungry hearted ones, sharp-limbed, keen-eyed, To Anne Knish

Madam, you intrigue me! Lolita

How curious to find in you, Lolita, Spectrum of Mrs. Q.

Fear not, beautiful lady, Epitaph

Courage is a sword, A SixpenceO B V E R S E

If I loved you, R E V E R S E

But I do not love you, Three SpectraOf Mrs. X.

You — Of Mrs. Z.

Madam, you are ever retreating, Of Mrs. Andsoforth

Old ladies, bless their hearts, Two Commentaries1. T O A N A C T O R

You are a gilded card-case 2. P H I L O S O P H E R T O A R T I S T

You are a raisin, but I am a nut! A Womanly Woman

You sit, a snug, warm kitten Lolita Now Is Old

Lolita now is old, The Shining Bird

A bird is three things: The King Sends Three Cats to Guinevere

Queen Guinevere, Ode in the New Mode

Your face Night

I opened the door |

|

References: books consulted and notes — |

|

Jacket 17 — June 2002

Contents page This material is copyright © Catherine Daly

and Jacket magazine 2002 |