|

Jacket 21 — February 2003 | # 21 Contents | Homepage | Catalog | |

Tom Clarkin conversation with Beat Scene editor Kevin RingThis interview first appeared in Beat Scene (U.K.), #42, Autumn 2002. It was conducted via e-mail, June 25 to July 1, 2002. You can link to Kevin Ring’s magazine The Beat Scene here. |

|

Kevin Ring: A lot of people will know you, at least in England, as the author of a biography of Jack Kerouac for Harcourt Brace in 1984. How did that come about?

Tom Clark: The commission to write a Kerouac life for Harcourt Brace Jovanovich came as a hand-me-down. Matthew Bruccoli, a professional entrepreneur in the biography industry who was overseeing a series of what he termed ‘brief but comprehensive’ illustrated lives of American authors for Harcourt, first offered the assignment to Lawrence Ferlinghetti, who declined, as did a second nominee, Robert Creeley; Creeley in turn recommended me, and I accepted. This was in 1981. I had earlier done several biographies, including one writer’s life, that of Damon Runyon, so I had some general sense of what I was getting myself into. |

|

Kevin Ring: You mention Paris Review, when did you become Poetry editor for them, and how?

Tom Clark: I took on that post in 1963, at the relatively tender age of twenty-two. Perhaps it was my innocence and inexperience which recommended me; at any rate I don’t think I’d yet betrayed any of the subversive tendencies for which my editorial contributions later gained a certain notoriety. |

| |

|

|

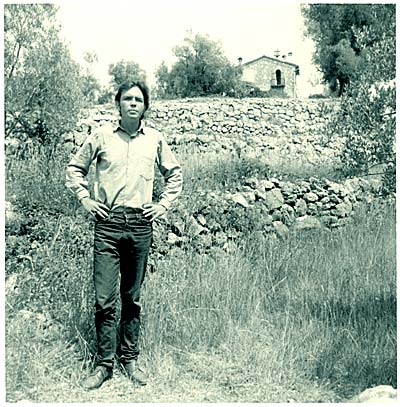

Tom Clark and a stone fence in Vence, France, 25 July 1966 |

|

Later on, after I’d moved back to the U.S., and wandered from New York to California, I continued on in the position, working in much the same fashion minus the periodic Paris junkets, until 1973, at which time it dawned on me that the universe has a way of repeating itself over and over, and that even (or should I say especially?) interesting avant garde poetry movements are not exempt from this. |

|

|

|

Kevin Ring: You mention being in England whilst first working for the Paris Review, I understand you first met Ed Dorn then. Tell us a little about your friendship with him then and about your own poetry magazine.

Tom Clark: Well, as I said, working for the Paris Review was technically not a ‘real’ job at all, since, though it took up a lot of time and effort in addition to being interesting fun, I wasn’t getting paid for it. My actual work, the first two years in England, was studying at Cambridge. The Fulbright paid me 500 pounds per annum, plus 100 pounds book allowance. Difficult as it may be to believe now, I pretty much lived on that, augmented by a few quid I earned by writing poems and reviews for the Listener, New Statesman, Encounter, Observer, TLS, doing talks and readings on the BBC, etc. |

| |

|

|

Joe was in a very sexy phase of drawing at the time: one cover I recall was a voluptuously involuted orchid, I believe that one was for Vice, of which I no longer own a copy. His cover for Spice, which I do have, was a drawing of a rumpled pair of jockey shorts — ‘Self Portrait, My Underwear, December 8th 1966, Joe Brainard.’ The cover of Slice was a beautiful set of disembodied girl’s legs which unraveled into a flowing abstract line from the hips on up; the letters ‘SLICE’ curled around her backside in a teasing erotic curve. |

| |

|

|

Most of the works I published in the Once series were somewhat or in some way more outlandish or strange than what I could cull for the Paris Review. Ted Berrigan in particular seemed to thrive on the opportunity to publish anything he wished. Ted (whom I’ve written about at some length in a memoir, Late Returns, from Tombouctou Books), challenged me with such pieces as ‘Poem for Ed Sanders’ — consisting of a single line of hand-printed block-cap letters, ‘I AIN’T GONNA DIE’ — and ‘Poop’: If I fall in love with my friend’s wife, she’s* fucked

|

This play was first performed

|

|

Other frequent Once series contributors included Aram Saroyan, who sent his first ‘concrete’ poems, and Ron Padgett, whom I still regard, looking back on it all, as perhaps the superior poet of that (‘our’ or ‘my’?) generation. Though I didn’t actually meet most of my Once and Paris Review poets until I’d gone back to the States and taken up residence in New York in 1967, Aram and Ron were notable exceptions. Kevin Ring: When did you move back to America? And when did the biographies of Olson, Creeley and Berrigan happen? What were the circumstances of those books?

Tom Clark: I came back to the U.S. in the early Spring of 1967. This was somewhat dicey since, as you’ll recall, there was a war on, and by dropping out of academia — I’d elected to ignore generous offers to continue Ph.D. work at Harvard, Columbia, Buffalo and New Mexico, among other places, a curious form of career suicide as things turned out in the long run — I was exposing myself to the military draft. Evading the military proved somewhat complicated, but, though I’d been trained to use a rifle during a compulsory ROTC program in college, I couldn’t imagine any good reason for killing someone, let alone doing it for the ‘reasons’ that were being offered. |

| |

|

|

During these Bolinas years I published my lyric collection Air (Harper & Row, 1970), and then a number of other volumes of more or less experimental poems, including four from Black Sparrow, Green (1971), Smack (1972), Blue (1974) and When Things Get Tough on Easy Street (1978), as well as Neil Young (Coach House, 1971), John’s Heart (Goliard/Grossman, 1972) and At Malibu (Kulchur, 1975); also the aforementioned autobiographical novel, Who Is Sylvia?. As there was the nagging problem of making a living, I took up freelance writing, doing several books on eccentric sports figures as well as my first ‘literary’ biography, The World of Damon Runyon (Harper & Row, 1978). |

|

|

|

Jacket 21 — February 2003

Contents page This material is copyright © tom Clark, Kevin Ring and Jacket magazine 2003 |