|

Jacket 21 — February 2003 | # 21 Contents | Homepage | Catalog | |

Pamela PetroThe Hipster of Joy StreetAn introduction to the life and work of John Wieners

John Wieners died in 2002. This piece was published in the Boston College Magazine in the Northern Fall of 2000. It is reprinted here with permission. The piece is 4,700 words or about ten printed pages long. |

|

|

|

A photograph taken in 1958 shows four handsome young men sitting on a stoop in San Francisco. Three, including the writers Michael McClure and David Meltzer, stare at the camera with flirty bravado. Only one, sitting by himself in a rogue shadow cast by something beyond the picture frame, glances away. He smiles good-naturedly, but seems uninterested in meeting the mechanical eye that will fix his image for posterity. Pain and suffering. Give me the strength

John Joseph Wieners was born in 1934 on Eliot Street in Milton, Massachusetts. (‘Look at his address,’ says Jim Dunn, a fellow poet and close friend. ‘He was destined to be a poet.’) Wieners is the only surviving sibling of four children who grew up in an Irish Catholic household in a middle-class neighborhood. Their mother, a waitress and housecleaner, worked in a defense factory during World War II. ‘She loved a good time,’ Wieners recalls, and ‘liked eccentricity up to a point’ — as long as a person put it to use within the conventions of middle-class ‘good taste.’ Wieners’s father was a maintenance man in downtown Boston, and it was to him that Wieners dedicated his volume Asylum Poems (Angel Hair, 1969). It was written when Wieners was in the Taunton State psychiatric hospital, where his father had earlier been committed for alcoholism. |

| |

Wieners in his 1954 entry in Sub Turri, Boston College’s student yearbook. Activities he listed included Writer’s Workshop, Sodality, and Minstrel Show. |

|

As a child, John Wieners (Jackie, the family called him) ‘was a little eccentric, maybe, and extremely bright,’ says his cousin Arlene Phinney. ‘He had a double promotion at St. Gregory’s. But what I remember best is his kindness.’ The excesses that Wieners’s publisher Raymond Foye would later characterize as his ‘extravagant personality’ were only hinted at during his years at Boston College. Wieners majored in English, worked in the library on a fellowship, and was literary editor of the Stylus, for which he wrote a poem about the death of the actress Gertrude Lawrence — his first publication. (Wieners has had a lifelong fascination with singers and actors. ‘He dreams of being a monied movie star,’ says Jim Dunn, ‘or a beautiful woman.’) A YOUNG POET

His career launched by O’Hara, in 1957 Wieners made for San Francisco in the footsteps of another Massachusetts boy, Jack Kerouac, whose novel On the Road had appeared earlier that year. Asked recently how he had liked life on the West Coast, Wieners replied dryly, ‘Well, the weather was much better.’ So was the social and artistic landscape. Wieners had moved west with a man named Dana, his lover of six years. When they broke up Wieners retired to his room at a boardinghouse in San Francisco’s red-light district and in less than a week composed a volume called The Hotel Wentley Poems (Auerhan Press, 1958; Dave Haselwood, 1965), which instantly became a classic of modern melancholy. It read, wrote Raymond Foye, ‘like a résumé of Beat poetry and of late romanticism as a whole: urban despair, poverty, madness, homosexual love, narcotics and drug addiction, the fraternity of thieves and loveless transients.’ It is a simple song:

Asked if he considers himself a Beat poet, Wieners leans forward in his squeaky chair, takes a drag on his cigarette, and courteously replies, ‘Yes, I do.’ Satisfied, he settles back again and waits in silence for the next question. Prodded into elaborating, he continues, ‘Well, the movement got some publicity, and I didn’t.’ He adds that working at City Lights, Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s famous San Francisco bookstore, ‘gave me a Beat image.’ At last. I come to the last defense.

After returning from San Francisco to the East Coast in 1959, Wieners did graduate work at the State University of New York, at Buffalo, and eventually settled in Boston, where he has remained. He continued to use drugs and alcohol, often excessively. ‘You don’t have the same self-protective faculties after you’ve taken narcotics,’ he said in a 1970s interview with Charles Shively. ‘The senses that the human organism has equipped itself with to take care of itself, to protect itself.... These all dissolve. I’d had two or three years of steady marijuana and peyote daily.... I was living in a visionary state, so that eventually the conscious faculties were being used to a minimum.’ |

| |

|

|

Another much-told tale features Wieners as a teaching assistant at SUNY Buffalo, arriving in class wearing pink hair curlers. These stories sum up Wieners as the benignly eccentric hero-poet, acting beyond the pale of conventional behavior, experiencing what others dare not. A kind of quirky, contemporary Romantic ideal. Because he was always scrupulously polite in his eccentricities, friends tended to mythologize him and protect him. But this was also the time that Wieners’s ‘courting of madness in the Rimbaudian fashion,’ as Jim Dunn puts it, came to a head. ‘Of course he was tragically wrong,’ adds Dunn. In the 1960s and 1970s Wieners was repeatedly hospitalized for a series of nervous breakdowns and episodes of insanity. (During one such episode Wieners’s sister Marian left her religious order to help their parents through the ordeal.) O poetry, visit this house often

‘Supplication’ was included in the volume Nerves, which was published in 1970 and is considered by many to be Wieners’s finest work. Raymond Foye points out that nerves can refer to tension and distraction or to strength and courage: the very poles on which Wieners’s psyche is stretched. Is it enough my feet blackend

One of the constants in Wieners’s life since his return from the West Coast has been the city of Boston itself. In an interview Charles Shively asked Wieners what label he’d put on himself as a poet — Black Mountain, New York, Boston, San Francisco — and Wieners replied without hesitation, ‘I am a Boston poet.’ For someone who in recent conversation defined the word ‘beat’ as ‘homelessness,’ Boston is in many ways the foundation that reminds Wieners he is ‘home,’ in both the physical and literary sense, whenever he starts to stray. Boston, sooty in memory, alive with a

Robert Creeley, when asked what made John Wieners a Boston poet, apart from ‘simply living there,’ replied, ‘“Simply living” anywhere is not at all as simple as it may sound. So many people are on their way to somewhere else, always — dragged along by various need, confusion, or ambition.... To be somewhere right now is not easy. John is a dear and absolute person of the city of Boston — it’s where he first found his life specific, I am sure. It’s his ground, his defining place, his language, his need, his limit, and his pleasure. As Charles Olson would put it, it constitutes “his habit and his haunt.”’ |

| |

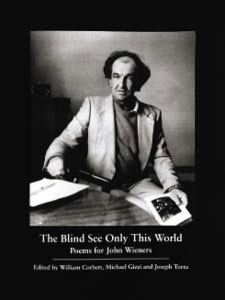

The cover of a tribute to Wieners, published in 2000 by Granary Books. Among the poets and novelists who contributed are Allen Ginsberg, Robert Creeley, Amir Baraka, Jim Harrison, Thom Gunn, Paul Auster, Gail Mazur, John Ashbery, Charles Simic, and James Tate.

|

|

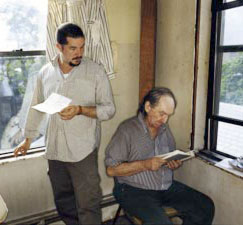

Wieners is not so much cavalier about his readings — or nonreadings — as he is unconvinced of the merit of his attendance. ‘Readings are best left to the young,’ he said once; another time he mused audibly before a rapt audience that no one really wanted or needed to hear his work anyway. In the fall of 1999 he did accept an invitation to read at the Guggenheim with his old friend Michael McClure, with whom he was photographed in San Francisco almost half a century ago. Jim Dunn recalls that he read for about 15 minutes then abruptly sat down halfway through the gig. ‘That was it,’ says Dunn, ‘he was done. He’d decided he was finished, and when John makes up his mind he can’t be budged.’ Raymond Foye agrees. ‘To encounter Wieners personally,’ he wrote, ‘is to meet with a man who seems entirely given to ephemeral gleanings, unused to the practicalities of the material world; to know him well is to behold his stubbornness and tenacity.’ |

|

Freelance writer Pamela Petro lives in Northampton, Massachusetts. She is the author of Travels in an Old Tongue (HarperCollins, 1996); her book on Southern storytellers was published in 2001. |

|

Jacket 21 — February 2003

Contents page This material is copyright © Pamela Petro and Boston College Magazine and Jacket magazine 2003 |