Ken Bolton

The Poetry of John Forbes

An introduction

This piece is 10,000 words or about twenty printed pages long. It first appeared in Thylazine magazine.

Jacket 3 is dedicated to the memory of John Forbes, and features five poems by Forbes, several photos, and poems and articles from a dozen contributors.

John Forbes was born in 1950 and died, at 47, in early 1998. He was a Sydney poet who lived the last period of his life in Melbourne. He leaves a relatively small body of work — but with a very high success rate: most of the poems repay attention. John’s approach to poems was, I think, formalist. But his thinking was brilliant and tended to the parodic: comic, compressed and, while seeking always to surprise, logical. His attention was fixed on the mechanisms of argument, both as rhetoric and as critical thought, but he was alert, too, to sound, diction, pattern. These last could inflect the poem’s direction, feed into it — as possibility, as sources of swift deviation or self-correction and as comic effect or comic avenue.

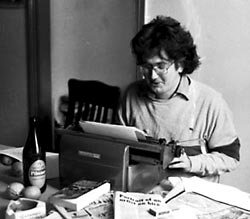

John Forbes, Fort Street, Petersham, Sydney.

Photo: John Tranter. The headline on the newspaper reads: Portrait of an artist on hire.

Forbes would have been aware that his poetry could be seen to have ‘themes’, but I doubt that these were often approached consciously, except as his general thinking focused on them and that they (naturally, therefore) came into play when he was writing. The writing grew out of the thinking (and would, ideally, act to further it). But the poems began with a form of words, a phrase, a tone that he recognised as a beginning — and he would take it from there. That is, the themes were those of the poetry because the themes were John’s quite apart from the poetry. The principal one, maybe it is the umbrella for others, is representation. John looks at representations, makes representations, considers all art to do so, and he examines them. Not only does he consider art as making representations but politics, philosophy, the culture generally — advertising, sport, national myths, TV, genres.

This is shaping as the beginning of a picture of John Forbes as some amalgam of Roland Barthes’s Mythologies, Frank O’Hara’s most demotic mode and with an admixture of Horatian latinity. Summing up John Forbes too quickly though is not to the point. The poems are rewarding individually. In my experience favourite John Forbes poems are almost endlessly reliable as inspiration. And then new ones keep finding their way into your affection and act similarly to prod one’s thought or writing. So it would be useful to move away from closing the book on John’s poems — as characterisations like Barthes/ O’Hara/ Horace, or capsule accounts of his themes, can tend to do — and attend to the poems in their singularity.

John’s work drew pretty interesting commentary in its time — some, inevitably, hostile and negative. Since his Collected Poems and earlier Damaged Glamour were both published posthumously, their reviewers have naturally striven to give some summation of the career as a whole. This has had the unfortunate effect of the later poems being read as if they were consciously ‘last poems’ and the earlier poems as in some cases leading to them, as if they were written as introductions to the later development rather than as dazzling artefacts in their own right. It has also led to the later moods and positions being read as final statements, or as a predicament, as the inevitable ‘end’ of a poet set on a wrong course. John’s poems didn’t kill him. He was looking forward to writing more and had he done so there would have been further change and development — of mood and tone, of form, and of thought and insight. This reception has generally approved of the work, and so the negative pronouncements have mostly been phrased as regret.

I think probably the major critical responses have been Ivor Indyk’s and Martin Duwell’s. Indyk’s does partake a little of the teleological and diagnostic: he looks at Forbes’s persona’s projected self-image in the poems, seeing a kind of ‘flawed grace’, a grace-plus-clumsiness. He aligns this with John’s (conscious? parodic? rueful?) concept of the role of the poet, and of the public poet in contemporary Australia. Some of the poems back this reading — as they do much else that Indyk says. (Two essays in Heat, and in Australian Book Review and Homage To John Forbes.)

Martin Duwell seeks to outflank the attraction, or availability, of thematic readings by beginning a typology of the poems’ forms. (“Reading John Forbes”, in Overland #154, 1999.) Which brings one to the poems — very much, I think, as they were conceived by the poet. My own favourites are: ‘Admonitions’, ‘Ode to Tropical Skiing’, ‘To the Bobbydazzlers’, ‘Jacobean’, ‘Phaenomena’, ‘Rrose Selavy’, ‘Breakfast’, ‘Floating Life’, ‘Ars Poetica’, ‘Lullaby’, ‘Bicentennial Poem’, ‘Monkey’s Pride’, ‘Speed, a pastoral’, ‘je ne regrette rien’, ‘Europe a guide’, ‘Love Poem’, ‘Lassu in Cielo’

Duwell’s typology begins with a principle he sees at work in all John’s poems: a torsional, powerful syntactic or grammatical structure which, if we think of it as algebraic, has constituent parts that are phonically and logically (and connotatively etc etc) surprising. Duwell recognizes poems that are ‘instructional’, that are celebratory, and poems that are lists and meditations. I seem not to have any instructional poems in my list. ‘Four Heads and How To do Them’ is the early example that most will nominate. ‘Europe, a guide for Ken Searle’ is a kind of candidate, but Duwell regards it as a list poem. (The categories aren’t discrete.) ‘Europe, a guide’ is one of a number of Forbes poems that deals in national characterizations. I love this one because in it are great jokes that often ‘sound’ funny, too

It begins —

Greece is like a glittering city

though only in a political speech

but Italians love bella figura

& misuse the beach. In Germany there’s

Kraftwerk & acres of expressionist kitsch.

Oil-rich Norwegians don’t need to ski

they just like it & Iceland is famous

for its past. Doing their physical jerks,

a quiet pride permeates the Swedes.

Denmark is neither vivid nor abrupt

& Belgians have a ringside seat

to observe the behaviour of the Dutch.

The French invented finesse but it’s

their self-regard that intrigues us.

Each nation is allowed approximately one attribute, sometimes with a modification or qualification. Each is amusing — but it is the coincidence of sense (and nonsense) with the many rhymes that has the poem crackle so. The first is the doggerel speech/ beach rhyme — which says the poem will be foolish and has us lower our guard. “Kitsch” hardly registers as a rhyme with “beach”, postponed as it is by the extra syllables that “& acres of expressionist kitsch” tacks on to the caesura that comes after heavy, heavy “Kraftwerk”. “(O)il-rich” is obviously planted in immediate echo of “kitsch”. Was the Norwegians’ “it” a rhyme, by intention, with kitsch/ rich? Because I think you can bet Forbes was writing on his nerve from soon after the first few lines, his ear whispering directions and interference to the logical side of the brain — where an enormous amount of knowledge was accessibly stored — which at a more conscious level was focused mainly on varying the sentence structures: Greece is like... but Italians believe... In Germany there’s... Oil-rich Norwegians don’t need to, and Iceland is famous for. The Swedes captain their sentence from its very end, their modifiers introducing them, followed by Denmark (the very next word — just as we think of the pair in history and on the map) which has negative epithets (“Denmark is neither vivid nor abrupt” though phonically those words are exactly vivid and abrupt) and the Belgians and the Dutch are properly coupled (“Belgians have a ringside seat / to observe the behaviour of the Dutch” — a full rhyme again, after ‘so long’, chiming with “abrupt”. A great deal is in the certainty of the tone (and its detachment) and the outrageous injustice of most of these certitudes.

The instructional as a mode is more fully evident in the politics of the description of the Swiss and the lines on Austria and the Czechs. I did the same art history course as John Forbes did, in the same year. I know the lectures, the books (Baroque and Rococo Architecture in Southern Germany and Austria), the slides he would have seen — and the slight air of shock German Rococo caused to student sensibilities, for which the plain old Baroque had seemed rich enough but which now seemed by contrast rather metaphysical and sober.

Consult my By Trail Bike

& Hot-Air Balloon Thru Middle Europe

for details of the Austrians & Czechs

but don’t forget Bavaria’s Octoberfest

or that Rococo architecture was designed

to be passed out under, pissed, & it’s

aesthetically edifying to do this.

This is true, or true-ish — appropriate at any rate. (It captures the intoxicating headyness of many Austrian and German Rococo ceilings and altarpieces, the ethos of the drunken German ‘student’ of the eighteenth and earlier centuries — remember The Student Prince? (young readers, do not even try!) — and, possibly, for John, the alcoholism and enthusiasm of our Austrian-born and -accented lecturer that year, regularly emotionally overcome and incoherent about the spirituality and idealism of such work.

The impulse of jeu d’esprit that has powered the poem thus far comes to the end of its arc — “For the rest: give Russia a miss” — with some effects of ameliorative diminuendo:

the Poles will appreciate hard currency

but only as a gift & the flesh-pots of

Split will leave you a physical wreck

The next line (“This guide stops short at the Balkans, / as it omits the Finns”) begins a sort of withdrawal. In part the focus shifts from verbal hi-jinx to the genre-status of the address. (“I won’t apologize / — many guides to Australia include / New Zealand or leave out Tasmania”) and then, in a way that is typical of Forbes, the thought becomes suddenly darker, more severe and more compressed than hitherto. It is great, I think, for the reader, this experience — as of an elevator suddenly felt beneath the feet as the descending journey begins abruptly to end, or of the temperature suddenly changing on the surface of one’s skin: Forbes gives a series of more conclusive and more seriously meant summative judgements — on Europe-and-America, and on Australia vis-à-vis those more powerful Western lures to our imagination: these are delivered as an aside, the rescinding of the sort of apologising that has preceded it and which in fact he said was no apology (“I won’t apologize”). —

Besides, if you remove the art, Europe’s

like the US, more or less a dead loss

& while convenient for walking

& picturesque, like the top of a Caran

D’Ache pencil case or chocolate box,

what do you make of a landscape

that reminds you of itself?

This is maybe pugnacious. It is deliberately graceless — as a corrective to our dependent views and self-conception. Europe’s foundational presence in our Imaginary is signaled deliberately as sourced in childhood’s pencil cases and illustrations — the ‘picturesque’. (John intends the irony of the reversal that has the New World find the Old World picturesque — though his argument is mostly concerned to invoke theories of the Picturesque — and criticisms of it (as formulaic, conventional, even timid, weak, insipid — corny — and hard to take as ‘real’). —

a landscape

that reminds you of itself? Is this why

the people are sure they’re typical

not standard? I can’t advise you on this

Here John seeks to deny Europeans the self-satisfaction he seems to feel they derive from their ‘place’ (endorsed by history, and geography, as central): “typical” is to suggest ‘types’ and the status of the Ideal: John proposes the more industrial, less Platonic, quality-control term of “standard”.

One of John Forbes’ ongoing preoccupations is Australia’s place in the world (culturally, as here, but also politically). His poems record different phases of his mood regarding this cultural measuring-against-the-powerful-centres, the originating centres, the metropolitan (and therefore judging) centres — and also record the conclusions of his thinking at different times. Sometimes he is fazed (and amused or struck by the spectacle he thus presents) — see ‘Europe, Endless’; at other times defeated, and bitter about it; at still others buoyant and would-be triumphant, as in the ‘guide for Ken Searle’. (Searle, significantly, was a painter friend of John’s who had not, at the time of writing, been overseas.)

I began to say how this sudden deepening of tone & focus — that deepens more quickly than we are ready for as we read — is typical of Forbes poems. One that immediately springs to mind — probably because it parallels ‘Europe, a guide’ in theme — is the late poem, ‘Anzac Day’. This is again a list I suppose. It pins brief characterizations to the different nations and their attitude as their conscripts face the horror of war. Rather than absurdity these characterizations seek to have the ‘justice’ of recognisably invoking the cliché that attaches to the various nation-types. (It is a smaller list‚ — the English, the French, the Irish, the Turks, the Scots, the Germans, the US — and it is perfunctory: the business in a poem about Anzac Day is to get on to the Australians once a contrast can be set up. “Not so the Australians,” moves us past the introduction.)

I think it is a very good poem. It is lightly meant, and offered, but (or “and”) it turns quickly but quietly at the end: from sentimental and sentimentalizing good cheer and national self-satisfaction with the Australian type — for which it begins to substitute Australia’s past — to a final position the poem doesn’t modify or move away from — disappointment. —

Unamused, unimpressed

they went over the top like men clocking on,

in this full-scale industrial war.

Which is why Anzac Day continues to move us,

& grow, despite attempts to make it

a media event

(I very much like the way the poem here connects the achieved national identity to the working-man of the Australian cities and to the union-managed work ethic of workers rural or urban.)

But the March is

proof we got at least one thing right, informal,

straggling & more cheerful than not, it’s

like a huge works or 8 Hour Day picnic —

“(I)nformal, straggling & more cheerful than not” carries for me the admiring pity of the day exactly — “Bless them all, bless them all, the long & the short & the tall,” as the song has it. The poem’s line of flight has moved from unexamined national self-satisfaction to this clearer and more reasonable view. But self-satisfaction and the unexamined are always John Forbes’ targets (“Not me, not my good intentions!” an early poem yells, miming the squirm of sudden bad-conscience). The poem concludes the sentence on the picnic, ending sentence and poem, with a reflection on the present as a falling away, a betrayal, or loss of something we had thought was ours and thought of as characterising us:

if we still had works, or unions, that is.

Forbes was an informed and political thinker. The poem grows out of and accommodates — as a subtext, it asserts or reminds us of — a particular perspective: the connections between mass mobilization and unionization; the sense of post-war entitlement; the fortunes of the Labor Party; in England the extension of suffrage in recognition of workers’ sacrifices; the democratic and communal colour lent to national self-image by the experience of mobilization and warfare; the achievement of the 40-hour week; the wartime government of Curtin; the roll-back of workers’ rights intended by Menzies and produced by subsequent Liberal governments — and the uncertain acquiescence to this by later Labor governments in the face of globalizing economies.

‘Bicentennial Poem’ — full title, ‘On The Beach, A Bicentennial Poem’ — has been dealt with in terms of its theme adequately I think by Ivor Indyk and, apart from the influence of the light Indyk has thrown upon it, it was anyway clearly an attempt at a more major and considered statement on Forbes’ part and most critics therefore look at it.

Indyk, and others, remark too on the poem as a statement of Forbes’ estimation of the possibilities available to the poet as public commentator or even public celebrant, judge, or spokesperson: “Your vocation calls / & you answer it,” it begins. A little too easily these lines are used to support the case that John did consider the more or less long-doubted feasibility of this function for poetry. Too easily — the words are taken to prove it. But even so it is obvious that Forbes is forced to recognize increasingly as time goes on that poetry is less and less central to our public, political and intellectual life. I doubt that the disappointment stems from there being no possibility of this specific ‘Bicentennial Poem’ — any Bicentennial poem — being able to command much cultural or political leverage today. The poem though is informed, I feel, with John’s disappointed acceptance of poetry’s diminished status and the public acceptance only of a diminished sphere of operation for poetry: that it should not be taken seriously if and when it treats ideas of any urgency or with any urgency.

Forbes was hip, smart, on the ball. But while society doesn’t mind approving of a poet or two — it does not wish to attend to them, take them seriously as critical thinkers. The world knows what poets should think and it will at best give a gold watch to one or two found to have spent a life celebrating, say, nature, or something steadfastly timeless, or dear to our hearts, and as long as all of the terms — “our”, “hearts” and “timeless” etc — are left unexamined.

Memorably the poem includes the great image of the poetic vocation, as increasingly side-lined and redundant — and resembling “something you did for a bet / and now regret, — like a man / walking the length of the bar on his hands, balancing a drink on his shoe”. You have to laugh.

*

A number of issues seem to me to need separating. John Forbes’s poems and mental orientation are, among other things, generally critical, deconstructive, analytical... and satirical. These things can be construed as ‘negative’. Secondly, Forbes’s mood and vision seemed to darken as he became older. (Mood and vision might themselves need separating.) Forbes’s own life could be seen as taking a more ‘negative’ turn as time wore on — his health became bad, he was increasingly set to be facing a lonely life — domestically, if not socially. The human condition? It suits some critics to see these as all indissolubly linked and to see the poems’ negativity confirmed as a fault — by the poet’s later expressed dissatisfaction, by any limitation seen in any late poem, and finally by his early death. If he had kicked on for longer would the already extant poems be therefore better? If he had grown gloomier would earlier poems or the ‘aesthetic’ be still more patently at fault? And — just as obviously — Forbes’s aesthetic did not especially relate to or depend upon drugs, did it? The answers are all ‘No’. And it seems truly gormless to suggest that poets must only express ‘nice thoughts’ or lead to ‘hope’ — or to fail to see the good in reasonable negativity. What poetry is approved I wonder by those who wring their hands at Forbes’s negativity, who hint that this intelligence — or an over-reliance on it — are at fault?

These same critics recoil from any vehemence in Forbes’s opinions and read them always as final, literally meant, and in no way provisional, ‘for effect’, relative, or theatrical. Hence the portrayal of Forbes as an educated yahoo decrying the values of art and civilization in favour of the comix pages. These critics draw a line between themselves and Forbes that renders them (in some cases fairly) as soft-brained, pious Houyhnhnms, nodding, genuflecting before truisms and mewling in a gently decorative way at the margin of life... lyric Eeyores in the Sandy Bog. John’s poetry sure jumped that fence.

*

John’s early poems I found, find still, exhilarating for their phonic texture, refreshingly modern diction and their alertness to the pieties of conventional poetry’s usages. ‘Rrose Selavy’ is a portrayal and enactment of infatuation. I love its innocence.

Julie the beauty of a tooth

& from the red & white checked table cloth’s back garden

when we’re quietly avoiding lunch

Julie begins to somersault

O facelift sing of Julie!

O mascara croon!

And Ireland green as hair let every crystal drop of whisky

flow to me

as a fish knife’s clatter falling sounds the name of Julie —

...

Julie breathing like a T-shirt after a swim

in Crete. Julie

in Rangoon a Chevrolet Impala

& in it Julie.

...

It’s the year slipping by

it’s the strange coast of Mozambique I’ve never seen —

...

Julie passing exams

“Everything Julie does John loves”, in this poem — as Laurie Duggan’s Martial poems more or less say.

(Kenneth Koch seems to be there, behind the poem, I think — but John isn’t swamped by him: there are other things going on.)

Very much of a piece is ‘Ode to Tropical Skiing’. I love its changes of scene and pace and slightly trippy yet caramel, Beach Boys, flavour. In some ways it reminds me of — though it is better than — the paintings of Tom Wesselman, his various ‘Californian Nude’ paintings.

I quote (and I’m sure, by the way, the Collected Poems is wrong and that the fourth line of the poem speaks of “that ice-cream” rather than “the”) —

Enjoy that ice cream, Gerald,

the sun sparkling

on its white frostiness

is the closest you’ll ever get to St Moritz

racing up the tiny snow fields on the side of a pill

as beside you the young girl’s

mirrored goggles reflect all Switzerland

like a chocolate box at the speed of sound

& like the ashtray he/ she you & it

are a total fucking gas

What else do I like?

happy to breathe again

like a revived dance craze

we gulp fresh air, our speeches to the telephone

so various,

so beautiful

And (a long-time favourite) —

Was that a baby

or a shirt factory?

no one can tell in this weather

(and) —

a chalet

drifts thru the novella where I compare thee

to a surfboard lost in Peru

I always supposed it was originally “shit factory” and “shirt factory” makes it funnier and more like Lautreamont/ Isidore Duccasse’s ‘chance meeting’... “beautiful as the chance meeting on a dissecting table of a sewing machine and an umbrella”. The mention of Peru for some reason suggests to me Samuel Johnson (whose ‘London’ and ‘Vanity Of Human Wishes’ John Forbes would have been unfashionably alert to, I think. But then John often seemed to me in the 70s a comically Johnsonian figure, ‘laying down the law’ in witty, well-weighted phrases. “Let Observation with extensive View, / Survey Mankind, from Chinas to Peru” are the Johnson lines. John is often closer to Johnson’s neo-classicism than to the seventeenth-century metaphysicals, I think. He shares Johnson’s force and finality of statement — and has something like Johnson’s troubled conscience, though I wouldn’t make too much of it).

The Forbes vocabulary of sounds like “nudge” and “fridge” and “annul” and “tube” is there — and “daze”, is it there, too?

‘Angel’ I love for its openness, all the “ands”, the ‘events’ that happen to ‘the young proteges’ — an idealization of teenage time wasted, of ‘love’ and ‘hanging about’. —

& I’d like to kiss you

but you’ve just washed

your hair, the night goes

on & we do too until

like pills dissolving

turn a glass of water

blue it’s dawn & we

go to sleep we dream

like crazy & get rich

& go away.

‘To the Bobbydazzlers’ I always loved though it’s hard to isolate bits from it and, as with the others, I love the whole poem. Its end (“I salute their luminous hum”) derives I think from Schuyler’s poem ‘Salute’ — and the poem before it in the Collected Poems, also called ‘Salute’, begins with the first line of Schuyler’s poem (“Each tree stands alone in stillness”). (So I guess it’s true.) And ‘Admonitions’, one of my first favourites — I still love it. (is it that I still see it with the eyes I had then? Or that I remember too vividly its impact? I don’t think so.) Written in collaboration with Mark O’Connor, it begins —

The happiest of cannonballs

is a burger,

a labour of love walking naked

along a beach

thinking: “Will our shit return to us in Paperback?

ah Sweeny Todd

will we ever forget “Him”?

swallow slowly with a glass

of water

The contrasted pairs of “happiest” and “burger” and “balls” and “burger”; the idiotic high-mindedness of a ‘labour of love’ that walks “naked along a beach”; the emphasis that lands on or pulls up short on “Thinking”, all this I like especially — and then “thinking” both gives the poem a new vista of possibilities to set out upon and retrospectively firms up the coherence or identity of the thinking subject, the cannonball/ burger that is also (“also”? — or is the burger “like”?) a “labour of love, walking naked”. I love the heavyness and mugging with which the religiously capitalized “Him” is pilloried. I love the parallel nuttiness of the denotations and the curiously balanced and opposed vowel sounds that follow:

I’m a migrating worker

I love a celestial fridge

Will apples happen??

Will glycerine flow like blood?

What’s the typical daze?

Is this the average spelling?

Not if we

can help it,

stumblebum.

And I like “happen” — do apples ‘happen’? Not usually. And “the average spelling” — usages designed to irritate pedants. I love the roll-call of names that comes later and “all come down & go to bed”, the adolescent toughness and (yet) inexact quality of “practising gutless emotions”. I love “or rainy afternoons chainsmoking the Alpine of my mind” and the following and final line of the poem — “let me disappear, let me go to the spontaneous bullfight”, the employment of the emotional feel of the line, and the gesture of its rhythms, over its denotative sense. Of course, the line is also Romantic in form, a fraught wish or appeal: ‘literary’ — and therefore funny too.

I like ‘A Loony Tune’ and ‘Floating’ — and ‘Drugs’ (“Rock stars, I don’t mean you!” is very funny — and:

Then by way by way of light relief

there’s my own favourite, alcohol

which is not really a drug

at all, just as the motto

‘lips that touch liquor will never

touch mine’ doesn’t mean

the girl of your dreams won’t be

a problem drinker. Even hippies

will, reluctantly, get pissed

& talk about tripping I won’t

because real acid is a thing

of the past & besides [etc]

‘Monkey’s Pride’ is another favourite —

like a packet of bungers facing Mecca

with lust in their hearts / hearts that resemble

Steve Kelen’s

or Gig Ryan’s face

inscribed on a banana, a whole bunch of them

‘Phaenomena’ I have always liked — though much of what I like in it I also find difficult and even ‘problematic’, as they say. It is deliberately beautiful in its treatment of the stars and astrology, fate and determinism — but I can never nail down satisfactorily the (grammatical) subjects and objects exactly — or how certainly, and when, the stars are in charge of the life or the individual is. But I love its sound and measuredness — like looking at the machinery behind a planetarium, gears steadily and certainly moving the planets and stars.

Pellucid stars chart my direction. You who

never hear our intent or voices, polish these

manoeuvres that, by instants, resemble you.

(Is “polish” an admonition, is it vocative or is it present indicative? For a moment I can’t tell and then I have forgotten and face the next problem — it’s like meeting too many interesting faces at a party.)

I sketch a course among attractions only to

invent you as a shining vehicle, yet as you

are, I am. Not aridity but removal steers me

Very little in John Forbes’ poetry reminds me of Frank O’Hara’s but ‘Phaenomena’ does a little. It is the quality of the address, merely — which reminds me of O’Hara’s in some of the latter’s poems for James Dean.

‘Baby’ and ‘Lullaby’ are nice, the first — tenderly, and ‘objectively’, domestic; the second having the so casually-sourced image of the night and stars “like bits of paint scraped off a window”. And the rueful joke that follows:

Instead

I sleep in the bed of a Great Man,

myself, too tired to cover up

the balanced odalisque of feeling

crashed out beside me

‘Speed, A Pastoral’ is one many like and which draws much commentary — partly because it is seized upon as stating some ‘position’ concerning the canon of Australian Poetry (Australian Poetry imagined as a classroom). I like the constant shift of purpose and attitude and the shift from depression to resolve (vis-à-vis Dransfield’s ‘leaving the room too soon’). The “Sir! Sir!” joke is very funny, “& heroin let him leave the room” very crushing.

‘The Stunned Mullet’. I love its beginning and the joke about a bronze at the Olympics, the desultory applause, and phrases like “only the fish thinks odd”, and “Captain Nemo, a fussy, European / judge of a good cigar” — Nemo, who “nurses an elaborate grudge / that brought him here”.

‘Ode to Doubt’. (“the pious grindstone of our self-regard”).

‘Humidity’ is a very nice poem — though I don’t understand the “two classes” and the “showers” bit. Does another class call this kind of rain something else?

‘(L)assu in cielo’ is a very good elegy and an evocation of its two poets (Martin Johnston and David Campbell), having them, in a dream, and across the divide of generations, meet.

John Forbes’s poem on the National Gallery’s Tiepolo painting, The Banquet of Antony and Cleopatra, dealt with that picture in about a hundred words and was a knock-out — concision was always John’s strength, and a kind of muscular wit. John was witty in the seventeenth-century sense — as it is applied to Marvell and Donne.

Here is how that poem begins —

Any frayed waiting room copy of Who

could catch this scene: flash Euro-

trash surveys a sulky round faced

uberBabe who’s got the lot — what else

could this painting mean, except that

superstars can will their luck, or

just how little raw envy’s hidden by

contempt, so words like ‘Wow! Great

Tits!’ or ‘Comic Opera Wop’ sum up

the observer, not Anthony and Cleopatra,

attached to pets and entourages — our

contemporaries minus coke and sunglasses.

‘Homage to Brian Wilson’ I like. It does strike me that a number of these poems revisit old territory for Forbes and try to force from the materials new truths or proofs — or to nail the same proofs again — and that the more successful of his later poems are generally elegiac in tone and more subdued than he had once been. One answer to this is, So what? Another is that this isn’t so (pointing to ‘Tiepolo’, ‘Queer Theory’, ‘Ode to Cambridge Poets’, ‘Spleen’). Another response is that we don’t know what might have been yet to come: these weren’t designed to be read as ‘last poems’.

I seem not to have been following Martin Duwell’s typology of Forbes poems that, at first, I had intended to work my way through, allowing it to select the poems I would write about. Peter Goldsworthy, in launching the book Homage To John Forbes, remarked that while initially he had admired the Forbes poems that he himself might conceivably have attempted, he had come over the years to prefer personally those that he could never by any stretch have written. For him these were Forbes at full bore: outlandish, heady, compressed, extravagant. I am not sure what my selection says about my taste — and I am not sure I should care — but I seem not to have landed upon any that Duwell would call a ‘meditation’. ‘On The Beach’ might be one, though it presents too much of a thesis to qualify, I think. (But then, Duwell didn’t have a category separate for ‘argument’.) John Forbes’s application of a quickly and powerfully twisting logic and of amusingly estranging image and analogy, is not natural to me, certainly, much as I enjoy it. One night of my writing life I spent or began — by accident — writing a poem that sought to understand (i.e., ‘translate’) a John Forbes poem that I’d never paid much attention to and had found initially rather difficult. My having found it so marks a lazy mind I think, because the poem isn’t too difficult — though I then proceeded to enjoy myself pretending it was as I bluntly anatomized it. (I carry this only so far in my own poem.) John’s poem was ‘A History Of Nostalgia’. It plays with the spectacle (the representation) of his contemplated differentiation of himself from his father, or from the pattern society would seem to offer, or to have offered. We can read ourselves into it. The poem telescopes past, present and immediate future successfully and amusingly. Great Expectations. The beauty of the poem’s beginning is in the sentence’s extension through clause upon clause. These seem alarmingly controlled, precise even, but to be hurrying towards some urgent conclusion that only becomes (grammatically and emotionally) more urgent as its end is deferred by yet another ‘narrowing’ (as it were) development or adjustment. —

The wish being father to the thought and mother

to your eager gestures — or at least the ones

a dulled sensibility remembers belonging to — you

stare off into the distance as hard as you can

as if some long desired form might materialise,

announcing just by its presence an end to change

& replacing this ridiculous static blur with

a perspective that creates a point of view —

something that slowly expands as you grow older,

broadening out like a real view does when you climb

a spur or wedge your way up a chimney: something

in short that []

Well, I have quoted a large part of the poem (and shall go on to quote most of the rest of it) and that is a strength of so many of Forbes’s poems: that they present seamless argument, a continuous movement of pressured thought. I leave only a little out in quoting the end of the poem. —

...Instead it disappears

in a bright flash & a puff of smoke at your feet

so that you’re left thinking, ‘Can this be it?’

&, sure enough, it is — you’re here, that’s all,

another miserable subject, composed of a few jokes

& catchphrases worn smooth with repetition

but at the same time almost statuesque, like a bust

of yourself in marble or bronze & mounted on

that plinth you used to lounge against, back

when you were still smoking Marlboros & worried

you’d come to resemble your father, not yourself.

Forbes didn’t have much time for nostalgia — but the word itself he loved and the practice was conceptually a target from the very beginning in his thinking. The poem would seem to be self-criticism (offered to us to try it for fit), examining projections, estimations, self-delusion — and the returns they might bring. (A key phrase in its sense can easily slip past unnoticed — “an end to change”, though the poem deals less with this wish than with the optimism before and panic after change.) It’s comic — “though sad enough if you think about it,” I can almost hear John say — the moves from the child ensconced away from view, scheming and dreaming, to a rock-climber noticing the way the distant view changes perspective and widens as he climbs, widens to the complacent addressing-of-the-world that an envisaged middle age is represented by, teeing off on a golf course (the wide view), and then the comic salvaging of mood as the “miserable subject” decides to adjust its score upwards — “but at the same time almost statuesque”. Then the poem applies ridicule to this — the bust, the plinth... that you have become, or imagine you have become, and which resembles what you had hoped to escape as you frittered away your youth.

The poem is fresh — and yet it uses many of Forbes’ regular moves and vocabulary: “resembles” and resemblance, “blur”, “static”, the nebulous “it” (the wished-for attainment or objective?) which ‘broadens out’ “like a real view does”. I think this qualifies as a meditation. It was a poem I had never read closely before and for some reason had found a little difficult — in the manner of earlier Forbes poems like ‘Love’s Body’ or ‘Topothesia’ — and had switched off from and put down unfinished perhaps.

All of Forbes’ poems are worth a close look if you are a poet or reader for whom his poems are at all congenial. And why would you be reading this if not? (Which reminds me of Forbes’s pleased reaction to that part of a review I wrote of his first publication, Tropical Skiing. In it I had said that some of his work acted to defend the poems from readers not smart enough to operate them properly. The poems (poems like ‘Admonitions’, I guess) acted to test the reader’s skill-level and sophistication. John approved of the remark — flattered, I guess, but, I would like to think, endorsing this idea. Partly this is smart-arsed youth pleased to be flexing its muscle — the same youth and flexing examined and dismantled in ‘History of Nostalgia’, and the same confidence or competence that had deserted me by the time I came to read that poem itself. Curious to be inflicting these views on the public again. —

Stylistically the poems attempt to be (in the best senses of these words) exemplary & pedantic. They attempt a kind of buoyancy & faultlessness that, aside from being very difficult, has to impress. They are demonstrations of how to be: like an ethical code taught in terms of manners and good form, a twentieth-century Book of the Courtier for the inner city, their perfection represents an ideal of behaviour, of success in general terms, of coping: buoyancy, equanimity, intelligence, ease, humour...

I went on to discuss ‘Admonitions’

Which, as an extended exemplary admonition, moves quickly, &, in the sense it cares least about, ‘disjointedly’, so as to test for the proper audience agility & to screen the reader for the correct responses (can a Canberra poet read ‘Admonitions’? Ideally not).

(from ‘Far-Out Sam, carnivore of the terrific’, in Magic Sam #4, 1978)

In my own redaction of Forbes’s ‘History Of Nostalgia’ — the poem ‘Dazed’ — I contrast our styles by deliberately making a meal of John’s neatly compressed poem in my longer, more rambling, discursive one. Just as the present essay presents a rather shapeless commentary on his shapely poems.

*

Forbes was the most inventive and witty of Australian poets, intellectually rigorous and insouciant by turns, bracingly corrosive and insightful when treating national myths and national self-regard or his own myths and self-regard. And he was, in his brilliant poems, extraordinarily funny as well as critical.

For many poets John’s attitudes and perspective on the ‘problem’ of Australian culture — its sustainability, its necessity, its dependence on the wider world — were definitive — as were his musings on that wider world’s imagined view of ‘us’.

He was emblematic of the figure and situation of the poet now. His work was compelling and relevant. In many ways he was the leading poet in Australia through the late 70s and onward. And he was influential: it has been noted in reviews of recent anthologies that Forbes is the only really discernible local influence at work amongst the young.

John was pronounced canonical almost from the time of his arrival. (David Malouf remarked in 1978 that John’s poetry seemed to naturally take up and improve a large part of the landscape of Australian Poetry, as though the space had just been waiting for it: a kind of necessity.) But Forbes’s centrality was also hotly contested by the spokespeople for the literary status quo and its values.

*

John has gone, but the poems remain — often dazzling, nearly always light and serious at the same time, and they help you feel smarter and more alive yourself.

He was endlessly rivalrous, generous, and unlucky in love — and routinely amused and appalled at his own behaviour.

*

Launching John’s book The Stunned Mullet I suggested that, though Forbes was usually referred to as an enfant terrible and was something else nastily French — the bête noire of the poetic establishment’s unconscious — his soul might be taken to bear a striking resemblance (‘if we could but see it’) to the young Audrey Hepburn: pure and light. MAYBE IT DID: he was an idealist, if often comically disappointed. Well, he was a realist — amused at his disappointment. Willing to learn from it, too.

In John’s hands poetry was not redundant but ‘spot-on’. Here is some more of that Bi-centennial poem:

astonished

trade union delegates

watch a man behead a chicken

in Martin Place — isn’t there

a poem about this

and the shimmering ideal

of just walking down the street?

not being religious

we bet on how many circles

the headless chook will complete

and won’t this do for a formal

model of Australia, not

too far-fetched, not too cute?

We can recognize ourselves in this — and the usual Australian political situation.

*

John Forbes’ ‘Letter To Ken Bolton’, which I will quote, is not typical of his poetry, working quite different parameters. It plays very much with the net down in terms of pace and intensity — which his work rarely sets out to do. But it does give some idea of his conversation: great jokes like those about the hearing-aid effect and property owners grinding their teeth; the joke-rhetorical phrasings like “though the quiet logic of misery asks” did in fact pepper his casual speech. I have cut a few sections in quoting (below). The whole was published in Overland #154, 1999.

Letter to Ken Bolton

Dear Ken,

I’m writing this out

of curiosity —

how do you write poems like this?

(& just doing this much

makes me realise

how hard the rhythms are)

I’m in Sydney & as

usual can’t imagine

how I could live anywhere else —

the names of the suburbs alone

& the way the nor’easter arrives

just when the day gets seriously hot

& stays till dusk

when things cool down:

“balmy” really is the word, despite

its connotations of ukeleles & islands —

not Sydney’s style at all (flying beetles

knock against my brother’s

uncurtained kitchen window) though I mainly

stayed at Mark’s

where the windows rattle

when a jet goes over

& the noise is almost as bad as people say it is,

each plane’s passing being accompanied

by the sound of thousands

of property owners grinding their teeth.

Today I killed cockroaches infesting O’Connor’s

& visited Arthur Drewe & Kerri Morey

who don’t share Mark’s blasé attitude

to “aircraft noise” — a title deed in Lilyfield acting

like an invisible hearing aid

you can’t turn off; which struck me as

a funny crack but now seems slightly shitty. I mean

even those old blokes in your poem

with their cigarettes in their T-shirt sleeve aren’t

impressed

& Bob Carr will lose

an election the Liberals couldn’t win.

Hypocrisy at least

comes easier to me

— I mean how can a thing be “slightly shitty” anyway?

& why does a typewriter made in the DDR (an Optima —

the Trabant of portable manuals)

have the question mark on the bottom of the key??

& if I’m going to write “anyway”

why not be completely saccharine

& write “afterall”? Which sentimentality

is what this letter is, or will be, about, via

your comments in ‘Dazed’ on ‘The History of Nostalgia’

(computers of the

future scroll both

poems in upper left

& right-hand boxes). But first a politics-of-getting-

your-ms.-accepted-by-A&R note: leave it out,

‘Dazed’ that is. The less JF

the better,

given JF’s the one

writing the reader’s report. So no matter how

glowing my remarks,

I can see Loukakis knocking you back: while

He really likes The Ash Range

I fancy it’s for corny reasons — you know

“the poetry of the real”

or as Peter Kocan once wrote, by way of deploring

some poet too “arid” or “clever”

“when Ted Hughes describes a falcon

you can feel its talons tearing out your heart”

Or something.

...

even so I think less JF would be a good idea.

Not here tho’ so back to me:

you’re right, of course

about that poem —

the feeling it engenders,

suggests?

celebrates?? is disgusting

& “Here We Go Again”

the nicest possible gloss / but art should hide

Art,

not the feelings of the artist, which in my case

is usually elaborate self-pity

& that same emotion suggests

the poem doesn’t go far enough:

instead of the statue being just a lump of metal,

solid & carved

into the likeness

of Nelson Algren on a bad day,

it should be hollow

& stuffed with the detritus

tourists drop

& COME TO THINK OF IT

there’s an early poem of mine that describes

my heart in just this way —

in ‘Clear Plastic Sugar’:

stuffed with butts

dream ends & the knack

of disappearing early

& of course,

that’s it!

I stopped disappearing early

& all my troubles stem from that!

(tho’ the quiet logic of misery asks,

why should I have to leave before the adults did?

Ranald Allen used to disappear early,

from parties & dances,

& always with someone I would have

dearly loved to disappear with myself — Here we go,

here we go —

but Ranald was always more spiritual than me

...

David Shapiro writes,

“Poetry never masters irony,

poetry is the present & constant mastering of irony”

which proves this letter isn’t poetry

although I think

my better efforts

present a sort of Tennyson-attempting-Clough

to his suave & tenured Baudelaire

...

It’s not just the rhythms of this sort of thing

I can’t begin to do,

I also lack the ...[etc].

The above is so unmistakably John Forbes, that, atypical or not, it serves well to illustrate much about his poetry. It deals with and ‘loves’ the everyday and suburban (suburban, coastal Sydney particularly). It is political, relishing the social indicators of things like cockroaches, and is observant about the politicizing effect of home ownership. It is concerned with ethics: with examination of his own errors and evasions and — especially significantly — is concerned with them as they are exampled through style, through aesthetics. Viz the remark about “slightly shitty”, the vigilance about “afterall”. It is concerned with aesthetics and with Poetry — his, mine, the world’s. It employs notions from, and references to, supposedly ‘high’ culture ‘alongside’ the popular, the mundane: Kamahl is mentioned and David Shapiro, Tennyson/ Clough and Baudelaire, and an imagined 50s TV show called You, the Ego. (The poem’s diction shifts registers, for affect, between high and low — but mostly is a contemporary and serious amalgam .)

Incidentally it has John’s love of the mooted existence of whole other worlds, other intellectual (etc) systems. (The famous early example is his ‘Four Heads and How To Do Them’.) John found their boundedness and self-sufficiency funny, preposterous, relativistically destabilising. The case in point is just the stylistic tic that has him unable to pass up the opportunity to evoke the communist world — represented here by Optima typewriters and the Trabant. There is the brief flirtation with (and invocation of) the hilarity of a cartoon-cliche episteme that has “balmy” ‘immediately’ suggest ukeleles, luaus, grass skirts and islands — another whole world — just as “Optima”, “Trabant”, “DDR” suggest a wrong-headed seedy communist dystopia.

The poem’s ostensible subjects are a typical enough roll-call of his concerns. One is the mystery of the mechanics and formulae of social behaviour and interaction: via the ‘Romantic’ (the quest for love) and a bathetically opposed ‘realism’ (of sex and parties). As well, Sydney is especially present, a Sydney he was revelling in while on holiday from Melbourne — and it is atmospheric, almost meteorological. (He is alert to the Sydney of (conventionally) democratic, working class elements. He notes the party-political situation — the noise pollution/ runway extension election.) Clearly the poem is written about the same time as ‘Humidity’. The same moths batter the same window. Friends and sociality feature strongly — individuals are named, their situations suggested. Finally there is Poetry. There is his poetry (specifically my poem ‘on’ his and his response to that) and poetry generally; there is poetry ‘business’ (my chances with Angus and Robertson Publishers, A & R); there is John’s pillorying of an opposed conservatism.

(Regarding poetry, he is for impersonality — or at any rate is against the spurious self of paraded sentimentality and badly disguised evasion. He is against the poetry of presence, against a poetry of powerfully rhetorical and naturally ‘transparent’ language — viz the crack about Kocan on Ted Hughes. He is against the confusion of good causes and good hearts with ‘the literary’ — (there are cracks about tree-hugging as well as his sarcasm about the critical opinions he attributes to Kocan and Loukakis).

Finally, the poem resembles but is unlike his other poems — and for him was not meant to join them, I’m sure. It is unlike them in having content that was not in principle publicly available. Some of his poems might be more obscure because ‘difficult’. But this one is basically — and relapses into being — a private communication. John wrote it in answer to a letter-poem I wrote to him (‘Perugia To John Forbes’, in my book Untimely Meditations). But where mine to him is public because the reader can be the addressee imaginatively (the poem basically reports on Europe from one Australian poet to another — like John to Ken Searle in ‘Europe, a guide’) John has more specific things to discuss — it’s a real letter. He talks about two things: the criticisms he read my poem ‘Dazed’ as making of his poem ‘The History of Nostalgia’; and, secondly, the advice that I should drop it from the MS I was presenting to A & R. John figured its presence would undermine the faith of their editor Angelo Loukakis in the disinterested quality of John’s opinions. John was at the time A & R’s poetry manuscript ‘reader’.

I should say that I didn’t think my poem made any criticism of John’s poem. I thought it was a self-deprecatory, pratfalling, pretended attempt to ‘interpret’ his poem line by line. That is, a joke about its excitingly baffling complexity and compression, a homage. John’s reaction is his usual hyper-self-criticism when it came to his own poetry. This literary self-criticism was partly just a matter of ‘standards’. John’s were very high. But the ethical self-examination was also typical of John — and it strikes me as a legacy of a puritanical Anglo-Irish Catholicism.

Though it’s arguable that ‘Letter to Ken Bolton’ is more interesting poetically (and in every way) than ‘Perugia To John Forbes’, still John wasn’t satisfied with it as a poem. He never talked about reworking it in the years after, not even to announce his having tried and failed. No. He abandoned the poem I think probably, as he wrote it.

Poem or ‘text’, the piece shows something of John Forbes’ orientation in the Australian literary world — opposed to the messily Romantic, to heart-on-sleeve factions, uncomfortable with A & R’s priorities (not much he approved got published), positively aligned with, for example, Australian Laurie Duggan and New Yorker David Shapiro. In passing, there is a deliberate echo of Frank O’Hara, significantly via one of the latter’s casual aesthetic maxims (the phrase “myth and message”).

Where poetry that was palatably assimilable to Australian traditions or paradigms won acceptance, John’s was resisted. John’s work was corrosively critical of many assumptions about ‘acceptable’ kinds of poetry and about conventional conceptions of poetic function or role — just as it was analytical, derisive, critical in relation to many cultural and philosophical stances in the broader culture. And it was correspondingly clear-eyed about the connections (mirrorings, echoings, causal relations) between the various spheres — the interactions of, say, popular culture, high art, economics, and politics, and relations between the national and international, between old world and new, between political realspeak and popular feeling.

The poems, and the attitudes that stood forth so clearly in them, made everyone nervous or exhilarated — or both. The early poems in particular were often rather joyous, insouciant and sharp. His poetry continued as it began, very alert to Art as politically acquiescent, complicit or compromised.

For many, John Forbes’s poems constituted a high-water mark against which to judge their own work, and the critical acuteness his poems manifested was a constant pep-talk. They were a reminder of what one might aim for and a defence against what one should avoid. Poets committed to those things John’s poems demolished, exposed, or rendered unallowable, naturally resisted: John’s books all drew many good reviews but they drew pointedly ‘faint praise’ as well — from the literary polite society whose sensibilities and cherished notions they abraded. In the early days John was routinely accused of glibness, superficiality, mannerism, of Pop-Art vacancy and (even) amorality.

This did not alter significantly till a greater gravity, and perhaps greater range of emotional tone, became evident with The Stunned Mullet (1988) and the later Selected Poems (1992). By this stage John’s brilliance was established as undeniable — but, for some, it was still to be located beyond some pale. One conservative anthology, for example, gave him an insulting ‘mixed-up kid’ style biographical note, the better to ameliorate his presence within its pages. He could hardly be left out — but he must not be let altogether in.

In this regard ‘A Kind Of Barking’, a review of Damaged Glamour (appearing in Five Bells, in 2000) is instructively normative — the sort of criticism-as-rearguard-policing action John Forbes’ work often provoked. Early in the article the author assures the reader that Forbes spoke with a genuinely Australian voice despite its being an urban one. Now Australians, more than practically anyone else, live in cities — and have done right from the beginning. The article’s implication is (as Forbes once put it) that the “locus of correct usage” is somewhere else — is it ‘the rural’, hmm? The thesis is advanced (though we recognise it instantly, as its foot comes through the door and long before it is fully unpacked) that Forbes’s poetry is held to be too smart and doubting ‘for its own good’ and that negativity is inevitably its final own reward: coarsening, null. What Forbes doubted that he shouldn’t have, the article fails to say. Nor does it explicitly claim that poetry’s function is not to doubt but rather to — what? — celebrate, praise, inspire? — which would have been a bit of a trap. Instead readers are warned away from Forbes’ poetry by a tut-tutting about fallen pride and bad manners. (And we are to take pause, too, because according to Les Murray Australians have a built-in ‘bullshit meter’ by which they judge things, often all too exclusively.) (The hand of Les Murray representing, for the reviewer, the kingdom of correct usage?) A rather amusing though small and relatively slight poem within Forbes’s work, ‘On the very idea of a conceptual scheme’, is read as nihilistic, fully intended, and of course not funny. It is instead seen to represent a decline into incoherence. (The first line of the poem gives the poem its title: the second line — “dogs set up a kind of barking” — gives the article its name.) It is a poem I think amusing and offered as literary gewgaw. It mourns losses of a certain kind, then affects to shrug them off with a playful absurdity.) The poem ‘Anzac Day’ the article presents as unmannerly slagging of other nations. All in all, it is as if to say, Let us pay no more attention to this unfortunate man — now that he has passed on and we can get some rest and get back to poems on, um, “the spiritually edifying nature of the architecture of Florence” — to quote, I think, Forbes’ friend Laurie Duggan.

In ‘Monkey’s Pride’ John describes the faces of poet friends inscribed on an imagined bunch of decorative glass bananas (that then morph into grapes). His head will not appear on one of the larger grapes at the top, reserved for the Great. It will be lost, Forbes says, among those lower down. He looks and he recognizes his own likeness — and he puts into its mouth, as an emblem, a phrase of mock protest he had used years before in a poem, a line I have always loved for so comically and blithely skewering the evasions and slippages his poems targeted and which they analysed and played with: “not me, not my good intentions!”

John is among the Great. His amused and amusing poetry — swift, compressed, exhilarating, cheerfully buoyant, acerbic, occasionally diffident and uncertain (that is, those things being perfectly and lyrically expressed), and brilliantly and usefully philosophical, tough and generous and ethical — sees to that.

John Forbes’ Collected Poems appeared from Brandl & Schlesinger, in 2001.

(Damaged Glamour was in preparation when Forbes died at the age of forty seven, in 1998, and was published later in the year.)

Homage to John Forbes (Brandl & Schlesinger, 2002) contains interviews with Forbes, accounts of his influence, opinions & character, and his poetry, from many who knew him well, including: Laurie Duggan, Peter Porter, Cath Kenneally, Cassie Lewis, Ivor Indyk, Gig Ryan, John Kinsella & Tracy Ryan, Pam Brown, Alan Wearne and others.

‘Perugia To John Forbes’ and ‘Dazed’ are in Ken Bolton’s ‘Untimely Meditations’ & other poems, Wakefield Press,1997.

it is made available here without charge for personal use only, and it may not be

stored, displayed, published, reproduced, or used for any other purpose

This material is copyright © Ken Bolton and Jacket magazine 2004

The Internet address of this page is

http://jacketmagazine.com/26/bolt-forb.html