This piece is 6,500 words or about 10 printed pages long.

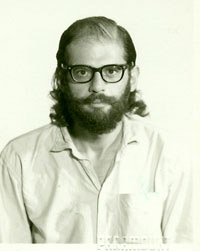

Allen Ginsberg, passport photo, 1966, copyright The Allen Ginsberg Trust, with permission. Source: http://www.allenginsberg.org/.

Most people do not visualize loaded missile launchers on the beach when they plan a Florida vacation, but apparently that’s what tourists found in Key West in October of 1962. A Bettmann/ CORBIS photograph found in Alice L. George’s Awaiting Armageddon: How Americans Faced the Cuban Missile Crisis indicates that these missile launchers were also a tourist attraction (69). The perspective is from behind four sightseers as they gaze across a highway at two ‘antiaircraft missiles’ aimed up, out, and over the Straits of Florida (George 69). Three women to the right lean back upon the hood of a car and take in the scene while other cars drive by on the highway. The fourth figure stands a little apart to the left, his left side slightly cropped by the frame. Though only the backs of the women are visible from the waist up, this man is viewed full length from the side and down to his left heel. His right foot and ankle remain concealed by the corner of the car hood. He wears shorts and white crew socks with two dark rings around the top of each while peering down into what seems to be one of those old Brownie cameras. He too snaps photos of missiles on the beach, though if nuclear war had broken out, it’s probably safe to assume that his film would have been ruined.

Like any photo, however, this one raises questions which undermine any one predominant meaning. How many people, for example, gather outside the frame, and who are they? How many other missiles and troops are deployed along this same beach? Is there any point in perhaps fleeing a nuclear war? Is any location ultimately safe, and if so, where is it? The caption nonetheless under the photo gives no indication who these people are or where they usually live. While they are referred to as merely ‘civilians,’ this seems obvious anyway, though today they might fall under suspicion as terrorist spies (George 69). No indication is otherwise given as to whether they are locals or tourists, and whatever they think or say about that which they witness remains unreported. Perhaps these people have already built bomb shelters and stocked up on groceries and are therefore prepared for destruction but, of course, there is no way of knowing.

This photograph demonstrates what Jean Baudrillard refers to in America as ‘the power museum that America has become for the whole world,’ but in another sense it captures an optimism which has no meaningful basis, unless perhaps it exemplifies a nation defending freedom to shop and work on a suntan (27). Despite the fact that many people panicked and fled to places unlikely to be targeted, the people in this photograph seem surprisingly relaxed, as if they are out on a picnic and such missile installations are an ordinary beach front feature (George 68-9). The simple gesture of taking pictures under such a circumstance necessarily implies faith that everything will turn out for the best, and that these missiles represent an admirable achievement, a work of modern art with a greater potential and of which the citizens are proud, so to speak.

Pride in weapons as an expression of a collective will, however, is necessarily limited by the very cynicism which imagines a need for these destructive objects, and within a democracy, individual voices inevitably arise to challenge the rhetoric which celebrates and deploys such ideological force. Written four years following the events that led to this photo, Allen Ginsberg’s poem, ‘Wichita Vortex Sutra,’ offered and continues to offer just such a challenge. Puzzling over the meaninglessness of a nation committed to supporting a repressive and unpopular regime in South Vietnam, ‘Wichita Vortex Sutra’ challenges media rhetoric and authoritative cold war technology with old fashioned verbal resistance. Where Baudrillard finds a ‘power museum,’ Ginsberg pushes beyond to expose the shaky foundation of duplicity and cynicism upon which this museum is built. Following about fifteen to twenty years of anticommunist rhetoric and the genuine fear of a nuclear war, ‘Wichita Vortex Sutra’ confronts and dismantles the meaningless justifications for the debacle in Vietnam. In doing so, it likewise opposes the present unfortunate tendency to repeat a comparable mistake. Given the current parallel rhetoric promoting the war in Iraq and perhaps soon again in Iran, it thereby seems appropriate to consider Ginsberg’s poem as a continuing discourse of resistance.

The poem opens with a command, ‘Turn Right Next Corner,’[1] and follows with a nearly meaningless slogan, ‘The Biggest Little Town in Kansas / Macpherson’ (110). While one fact is undeniable, the place must be McPherson, whatever is meant by ‘The Biggest Little Town’ remains however uncertain. Perhaps residents of McPherson are proud of their town. Surely, some of them must be, or perhaps such a slogan is simply a product of the Chamber of Commerce. In either case, an outsider is unlikely to learn much from this claim. If McPherson experiences a steady increase in population, when might it cease being little, or does the idea that it is a ‘Biggest Little’ allow for some leeway in avoiding the possibility that it might someday become just another of many small cities? While such questions are not of great importance to anybody living in any town, including those who live in McPherson, the idea that the speaker parrots a billboard sets up the remainder of the poem, a poem which finds such verbal nonsense not only ubiquitous but deadly.

This doublespeak seems only a quaint maxim through which a town council chooses to distinguish itself, and nothing much in the opening lines occurs to dispel this notion. The text rather situates an industrial town within a rural landscape where businesses close likely at five and nights thus come early:

Red sun setting flat plains west streaked

with gauzy veils, chimney mist spread

around christmas-tree bulbed refineries — aluminum

white tanks squat beneath

winking signal towers’ bright plane-lights

orange gas flares

beneath pillows of smoke, flames in machinery —

transparent towers at dusk (110)

The speaker establishes a visual context not a lot unlike that found in the photograph of the civilians admiring the missiles on ‘George Smathers Beach’ in Key West, but in this instance, large fuel tanks and signal towers are featured (George 69). Even potentially noxious emissions such as ‘smoke’ are neutralized as ‘pillows,’ and any clue that anything is amiss remains submerged within the family man dream of this scenic interlude.

Evidently, however, Rogers S. Cannell provides a map in his 1962 publication from the Emergency Planning Research Center at the Stanford University Institute, Live: A Handbook of Survival in Nuclear Attack which indicates that McPherson is only about twenty miles south of a Strategic Air Command (SAC) bomber base and about fifty miles north of another in Wichita. As Cannell explains, ‘an attack upon the United States would almost certainly begin with a strike on any military bases which could rapidly strike back’ (3). McPherson thus squats directly between two critical targets, within a vortex perhaps of dubious radiological latency. In all likelihood, some residents of McPherson work at and commute to either of these bases. At any rate, it hardly matters whether it’s a biggest little town or a small city. ‘In advance of the Cold Wave’ Ginsberg continues, ‘Snow is spreading eastward to / the Great Lakes,’ and the citizens of McPherson, some of whom may have been on vacation in Key West in October of 1962, might rest assured that only snow is likely to fall on the lawns of this sleepy polis (110); by shifting the ‘v’ to an ‘r’ in ‘wave’ and dropping the ‘e,’ however, even this simple account of words heard over a car radio carries ominous overtones and so hints at the idea of nearby farm silos concealing nuclear ICBMs.

Into the vortex thus rushes this ‘PERSON appearing in Kansas!’ and the poem gathers momentum while invoking both Whitman, ‘who came from Lawrence to Topeka to envision / Iron interlaced upon the plain,’ and ‘Telegraph wires strung from city to city O Melville’ (110-1). While Ezra Pound is associated with the ‘Chinese written character for truth,’ the relationship between Ginsberg’s poem and Pound’s ‘Vortex’ manifesto is undeniable (118):

The vortex is the maximum point of energy.

* * * * * * * *

You may think of man as that toward which perception moves. You may think of him as the TOY of circumstance, as the plastic substance RECEIVING impressions.

OR you may think of him as DIRECTING a certain fluid force against circumstance, as CONCEIVING instead of merely observing and reflecting. (80)

Into this plunge the poem takes charge of the discourse while situating itself within a distinctive tradition. Although the opening sections serve primarily to acknowledge a fundamental need for people to physically contact and connect with others, ‘As Babes need the chemical touch of flesh in pink infancy,’ this ‘Vortex / of telephone radio aircraft assembly frame ammunition / petroleum nightclub Newspaper streets illuminated by Bright / EMPTINESS’ opens a vacuum into which rushes an abstract and disingenuous language which the poem seeks to confront.

While the text is not populous, neither are people absent, as suggested by Paul Carroll in ‘I Lift My Voice Aloud, / Make Mantra of American Language Now... / I Declare Here the End of the War!’ (307). Ginsberg rather refutes lack of human contact as resulting in ‘Idiot returning to Inhuman — / Nothing — ’ (111). He accordingly presses this nothingness by contrasting one ‘tender lipt girl, pale youth’ and ‘boy bicept — / from leaning on cows and drinking Milk / in Midwest solitude’ with ‘staring Idiot mayors / and stony politicians eyeing / Thy breast’ (112). Perhaps Carroll found it ‘vacant of people [...] (with the exception of the faceless crowd in Beatrice, Nebraska)’ (307) due to his own urge to reinforce Ginsberg’s reputation as a ‘priestly legislator” (306), but though this pontifical characteristic urges the poem, it is finally less significant.

Carroll’s decision to focus on the mantra unquestionably allows for a messianic reading of the poem as a ‘dispensation of peace, compassion and brotherhood for all Americans,’ but otherwise he does not fully account for the intensity of the skepticism engendered by the duplicity of both the government and media (310-11). More critical is Ginsberg’s persistent appraisal, a democratic appraisal available to anyone, and this poem principally works as an act of civil disobedience:

Is this the land that started war on China?

This be the soil that thought Cold War for decades?

Are these nervous naked trees & farmhouses

the vortex

of oriental anxiety molecules

that’ve imagined American Foreign Policy (122)

Asking if the earth is responsible for human fears and paranoia is obviously absurd, as if such attitudes might be endemically due to the ecosystem, but so too this passage is funny. Through a ridiculous anthropomorphic characterization of ‘naked trees & farmhouses’ as ‘the vortex / of oriental anxiety molecules,’ cultural fear of foreign otherness is likewise made ludicrous. Obviously, only people are capable of creating an ‘American Foreign Policy,’ and the suggestion here is that such policies might easily be reimagined without the insular and ignorant fears which lead to aggression.

In terms of Carroll’s urge to reinforce heroic ideals of the poet as somebody worthy of elevation to a pedestal, it might be wise to stop and consider the consequences of such a move. Howard Zinn speaks of this tendency in regard to presidents in his book on The Twentieth Century: A People’s History. Claiming that ‘histories [...] centered on political’ personas ‘weigh oppressively on the capacity of the ordinary citizen to act,’ he continues in an appropriate passage well worth quoting in full (281): ‘The idea of saviors has been built into the entire culture, beyond politics. We have learned to look to stars, leaders, experts in every field, thus surrendering our own strength, demeaning our own ability, obliterating our own selves. But, from time to time, Americans reject that idea and rebel’ (281). And here lies the deficiency in Carroll’s analysis; he subverts Ginsberg’s aesthetic of rebellion in order to elevate his celebrity. Instead of seeing poetry as a tool through which a variety of people might raise a variety of voices in a democratic effort to move a culture toward a more inclusive, dynamic, and sustainable social organism, Carroll falls into the blind trap of Ginsberg’s renown.

Much more relevant is Ron Silliman’s observation in a February 14, 2006, blog post that this poem emerges collectively amongst friends with a tape recorder during a time when the United States engaged in senseless carnage (http://ronsilliman.blogspot.com/). The ‘speaker’ as celebrity appropriately drops into his community, and then, from within this community of lovers and friends, the poem enlarges to contend with a government propaganda machine which no longer has any interest in representing anybody but a very exclusive community of corporate capitalist war profiteers. At the same time, the rural infrastructure of family farms and small family businesses within the greater community through which this poem travels suffers serious assault from the same corporate behemoth, not to mention that the vast majority of soldiers are draftees who have been forcibly removed from viable human communities.

Because this poem grows in conjunction with a community of artists, it therefore remains open to broader possibilities engendered by this human proximity. What Silliman and Carroll both fail to address however extends from Ginsberg’s methodical exploitation of the notion of spectacle common to the period. Protest in the 60s becomes a multimedia theatrical event, and the words of a poem are only a part of some much larger collective which simply happens. As a persona in the open theatrical frame of the public square, Ginsberg merges with an expansive and widespread resistance that engages the media as a freewheeling circus. In effect, Ginsberg was every bit as media savvy as the governing corporate apparatchiks, and his poem, as part of this performance, additionally dares to address those whose job it is to snoop on what they think of as his subversive persona.

Ginsberg thus pokes fun at those who keep him under surveillance, and in doing so he undermines this notion of political celebrity. The contrast between Ginsberg’s text with those of the anonymous bureaucrats who compose his FBI files is striking:

Truth breaks through!

How big is the prick of the President?

How big is Cardinal Viet-Nam?

How little the prince of the F.B.I., unmarried all these years!

How big are all the public figures?

What kind of flesh hangs, hidden behind their Images? (112)

Certainly, his intent is meant to be provocative, to mock those agents who follow his every move, who read his words, and who attend his readings. And again, Ginsberg is incredibly funny. One can easily imagine the game of spotting the agent in a crowd at a poetry reading. The message here however concerns the ordinary; these power brokers are merely common sacks of meat on racks of bone, naked underneath formidable suits, and so the illusion of difference as a deployment of power is fittingly punctured.

With ironic humor, Ginsberg targets the fact that these public representatives, these people who work for us, are in the nasty habit of concealing the truth about their own motives and actions. Yet they spy on him despite the frank openness found in his poems. Ginsberg’s FBI file as collected in Lewis Hyde’s anthology of criticism reads vaguely as follows: ‘In an [censored] contained in our files, the [censored] quotes the May 16, 1965 issue of the Czechoslovakia publication Mladá Fronta in which an editorial appeared regarding GINSBERG,’ after which a more explicit complaint cited verbatim from the publication thus appears again in the report. This section merely reports his deportation from Czechoslovakia for sexual promiscuity. So, oddly enough, the public record, even while remaining public, subsequently gets hidden away and censored so as to protect naïve readers from some dreadful secret which isn’t (244). Likewise, another piece of his file refers to a photo ‘where he is pictured in an indecent pose’ (250). Apparently, this is about as descriptive as the agent is willing to risk. Rather than explaining what is meant by an ‘indecent pose,’ the agent chooses to conceal the photo ‘in a locked sealed envelope marked “Photograph of Allen GINSBERG — Gen. File: Allen GINSBERG”‘ (250). After all this, it is ‘placed in the vault [...] for safekeeping’ (250). The primary goal of this panoptic agency seems geared then toward stalking somebody harmless and then concealing that which is already known. Because Ginsberg dared openly express (gasp!) his own (homo)sexuality and, hence, his humanity, he is also post hoc ergo propter hoc associated with communism in another document, supposing, one might guess, to increase the threat, perhaps of incarceration, should his homosexuality is not prove sufficient (248)? Whatever the case, Ginsberg’s openness negates the ability of government stooges to accumulate secrets, so they simply conceal their intentions.

At any rate, ‘Wichita Vortex Sutra’ continues by challenging the manner in which news is disseminated and others, as enemies, such as Ginsberg, are stereotypically portrayed. No doubt, little has changed, and if enemies are needed, then they shall be found, as can be seen in Ginsberg’s FBI file. This poem nonetheless illustrates how enemies are subjectively manufactured and that, individually, no one need comply with the process. As a pastiche of road trips through a Midwestern night, the first assessment of how the media reinforces and implants stereotypes occurs while:

Approaching Salina,

Prehistoric excavation, Apache Uprising

in the drive in theater

Shelling Bombing Range mapped in the distance (112)

The threat of nuclear war remains ubiquitous, and Salina, as due north of McPherson, is even closer to the SAC base. But when Ginsberg places the ‘Prehistoric excavation’ in conjunction with the movie title, he unravels the discrepancy between concrete evidence of pre-Columbian cultures since decimated by colonialism and the myth of progress as a viable justification for genocide. In a single four-word line of poetry, pop culture is exposed not only as historic revisionism, but also as current policy both domestic and foreign. And anyway, why shouldn’t the Apaches defy a hostile displacement? The poem does the same. When Don Byrd writes in The Poetics of the Common Knowledge that ‘knowledge [...] is the condition of action that permeates the space of a community,’ the consequences of inaction remain implicit: that there shall either be thus no space for community, or that others shall act to fill that same space (23-4). Are rebellious Indians then unreasonable, and so also the Vietnamese? Was Malcolm X unreasonable as well when he referred to the 1963 civil rights march on Washington as ‘nothing but [...] a picnic, a circus [...] with clowns and all,’ and so deleterious to African American ‘militancy’ (160)? This poem calls for an equivalent unreasonableness. This is a poem which ruins the reasons and shoves beyond toward a site of radical remaking.

As the very legitimacy of the United States as a nation is called into question above (having displaced so many other nations), this first section of the poem establishes Ginsberg’s own voice as adequate to the task of invalidating the ubiquitous propaganda serving to promote the war in Vietnam. Prior to attacking the legitimacy of language as spoken by people such as McNamara, Johnson, or Humphrey, among others, Ginsberg celebrates his ability to invoke his own distinctive sound:

Language, language

black Earth-circle in the rear window,

no cars for miles along the highway

beacon lights on oceanic plain

language, language

over Big Blue River

chanting La Illaha El (lill) Allah Who

revolving my head to my heart like my mother

chin abreast at Allah

Eyes closed, blackness

vaster than midnight prairies

Nebraskas of solitary Allah,

Joy, I am I

the lone One singing to myself

God come true — (113)

Ginsberg most definitely demonstrates his ability to ‘sing’; the complex alliteration of the ‘b’ and the ‘l’ sounds fluctuate with the soft and assonant ‘ah’s,’ but a variety of other sounds combine as well to render this passage exceedingly rich. While the repetition of the long ‘i’s’ emphasize his comfort and pleasure with optimizing the quality of his own voice, his presence at the same time occurs within a magical and sacred continuity as connected through his mother, a connection likewise softened by a meaningful sequence of ‘m’s.’ Read aloud, this passage succeeds in positing an authoritative stamp upon the speaker’s democratic right to challenge official governmental authority, and in the second section he does so with a vengeance.

Wasting no time whatsoever, part two of the poem again opens with a command, this time to ‘Face the Nation,’ a straightforward reference to the CBS news program which features interviews with a wide variety of public political figures (115). Meanwhile, this reference also works to orient the speaker while traveling:

Thru Hickman’s rolling earth hills

icy winter

grey sky bare trees lining the road

South to Wichita (115)

Rather than passively accepting slogans as having mere surface meaning, the reader or listener is similarly encouraged to apply critical thinking to how words are used. In this way, Ginsberg considers the command as a challenge, and the name of the television program is accordingly called into question. Appropriately, the first major public official to be skewered is Robert McNamara, the Secretary of Defense at the time when this poem was written:

MacNamara made a “bad guess”

“Bad Guess” echoed the Reporters?

Yes, no more than a Bad Guess, in 1962

“8000 American Troops handle the

Situation”

Bad Guess

in 1956, 80% of the

Vietnamese people would’ve voted for Ho Chi Minh

wrote Ike years later Mandate for Change

A bad guess in the Pentagon

And the Hawks were guessing all along (115-6)

In other words, the government of the United States is here involved in a war against a people led by a man who prior to the war enjoyed an 80% approval rating, and Ginsberg furthermore paraphrases a former president to provide supporting evidence. As if that were not bad enough, when the United States sent soldiers to fight in Vietnam, these soldiers battled the very same people who admired and quoted the American Declaration of Independence in a similar document of their own (Zinn 171). And while McNamara claimed as early as ‘February 19, 1963’ that ‘Victory is in sight,’ this war only ended for the United States ten years later in the face of an ignominious retreat and societal disintegration at home (Zinn 203).

Ginsberg’s criticism is comprehensive, however, and through the inclusion of headlines, he demonstrates the complicity between mainstream media outlets and governmental Orwellian doublespeak. In this regard, it appears that little has changed. Rather than admit that a horrible mistake has been made, government officials continue to generate excuses for continuing a messy and disreputable war:

Put it this way on the radio

Put it this way in television language

Use the words

language, language:

“A bad guess”

Put it this way in headlines

Omaha World Herald — Rusk Says Toughness

Essential for Peace

Put it this way

Lincoln Nebraska morning Star —

Vietnam War Brings Prosperity (117)

In this manner, the second headline exposes the cynical and self-centered dissimulation at the heart of the first. Simultaneously, the both headlines fail to account for the human physical and psychological cost of the war. Even by this early date, the evidence indicates that the American effort in Vietnam is unmistakably calamitous, yet Rusk ironically insists that peace can occur only through an application of increasing violence. The notion of war as additionally generative of prosperity is ultimately reprehensible. Those who profit from the suffering of others unconditionally warrant indictment as war criminals, for these are the enablers.

As the Secretary of State, Dean Rusk not only has ample opportunity to speak to the media, but he is expected to do so. It comes as no surprise then to find a transcription of his March 22, 1964, interview with Face the Nation and his subsequent defense of McNamara’s 1963 claim as cited above by Zinn that ‘Victory is in sight’ (203):

Mr. Kalb: [...] It now appears as a result of the McNamara mission that more money may be invested in South Vietnam, but it does not appear as though there is any major change in emphasis in our policy. Do you feel sir —

Secretary Rusk: [...] There would be no problem in South Vietnam if their northern neighbors would leave them alone. We believe that the South Vietnamese are determined to insure their security and independence, and we also are determined to help them on that. Now, Secretary McNamara came back and made a full report on this. He found that there were strong reasons to believe that our present policy can be successful; that the South Vietnamese are determined to get on with the job; that there are important forces and material available there and present there that have a good chance of doing this.

Mr. Lisagor: But, Mr. Secretary, our commitment was no less deep before Secretary McNamara went out there on this last trip. What has happened now that makes you more encouraged that the situation would be reversed, turned around in South Vietnam, since it seemed that things were not going very well in the battle against Communist guerrillas before he went out there? (163)

Other than iterating the ‘vigor and leadership’ and promising success, Rusk’s reply to this question is not worth repeating; instead, one might be left to wonder what he actually means by ‘important forces and material,’ as well as what Mr. Kalb’s question might have been had he not been interrupted. And yet one cannot help but notice the verbal elements which allow for escape and evasion, the lack of commitment to a real sense of purpose other than that Rusk ‘believes’ that some nebulous ‘forces and material there [...] have a good chance’ of getting ‘on with the job.’ Such nonspecific phrasing and assertions of belief, of course, allow for a lot of wiggle, and when so many human lives are at stake, those people deserve rather straightforward specifics. A television viewer of this discussion is instead abandoned to decode meaningless platitudes.

In the meantime, the nuclear threat remains as a constant. As proxy to the so-called cold war, Vietnam increasingly blazes. The nuclear threat, however, has not vanished for Ginsberg in 1966, and neither has it vanished today. In fact, contemporary war making has instead taken on an unanticipated form intended as a means to dispose of nuclear waste. Just as Agent Orange continues to claim victims in Vietnam forty years following this poem, depleted uranium munitions are deliberately deployed today in Iraq. Rob Nixon reports in ‘Our Tools of War, Turned Blindly Against Ourselves,’ an article appearing in the February 18, 2005, issue of The Chronicle of Higher Education, that although casualty rates (if counted at all) are commonly calculated as limited to the duration of a conflict, both Agent Orange and depleted uranium carry rather ‘long-term implications.’ Both poisons guarantee a type of warfare which continues for ‘untold years’ (Nixon). Unlike the ability of colonial imperialism to bury past atrocities beneath time and rhetoric, these toxins continue to produce ‘an abnormally high proportion [... of] stillborn or malformed infants’ (Nixon). A Google/ image search turns up a shocking array of Agent Orange or depleted uranium birth defect photos. In terms of the latter, the first Gulf War provides plenty of evidence. Considering the scope of that war in comparison with the present conflict, it is probably safe to assume that large portions of Iraq are now rendered uninhabitable, and yet the current Bush/ Cheney administration threatens using nuclear ‘bunker busters’ any day now against Iran.

This poem objects to what today are plainly war crimes. The spraying of Agent Orange in Vietnam has not ceased to be a war crime because it happened forty years past, and neither shall the distribution of depleted uranium dust. The photos of deformed children from areas sprayed with Agent Orange are recent. For this reason the war in Vietnam continues today and thereby conflates with newer inhuman wars. In any case, Ginsberg addresses this nuclear threat as endemic to the entire verbal and obfuscatory muddle:

Sorcerer’s Apprentices who lost control

of the simplest broomstick in the world:

Language

O longhaired magician come home take care of your dumb helper

before the radiation deluge floods your livingroom,

your magic errandboy’s

just made a bad guess again

that’s lasted a whole decade. (120)

Further conflating the arms race with the development of television results in a seamless double entendre, though neither possible interpretation is at all ‘sexy.’ The radiation he refers to might be either that of the television screen or a bomb dropped upwind, and today the single decade stretches into a fifth. Despite Cannell’s nutty claim that a ‘post-attack world would be worth surviving for,’ or that ‘democratic values can endure hardship [... and that] the environment would be as safe after [nuclear] attack as the world most of us entered at birth,’[2] one might easily presume that ordinary people, even those who might believe such nonsense, would prefer a humane alternative. Who, we might also ask, does he mean by ‘most of us’ and, please, what are the options?

Practical alternatives to any kind of war can only occur when people are nevertheless considered in concrete terms as physical beings with valid concerns and emotions. But first these concrete characteristics must be understood as universally shared, and that this universality remains consistent whether such people live ‘in Nebraska same as Kansas same known in Saigon / in Peking, in Moscow, same known / by the youths of Liverpool’ (Ginsberg 117). When those who control the discourse surrounding and promoting a war maintain that ‘ Toughness / [is] Essential For Peace,’ they are plainly disingenuous (Ginsberg 117). Rather than empathy, these people resort to vilification in an absolute failure of human compassion. Ginsberg conversely cites government spokespersons as replacing this concrete human compassion with a recitation of statistics as supposedly representing success:

Viet Cong losses leveling up three five zero zero per month

Front page testimony February ’66 (117)

In terms of success, of course, these numbers are trotted out as if they accurately measure the relative score, as if appealing, undoubtedly, to the habitual dead metaphor of war as a sporting event instead of plainspoken brutality and murder. As passive consumers we are herein expected to believe that we win a game which all but the profiteers really loose. War is never a game, and these numbers simply conceal the truth. Zinn puts it thus simply:

from 1964 to 1972, the wealthiest and most powerful nation in the history of the world made a maximum military effort, with everything short of atomic bombs, to defeat a nationalist revolutionary movement in a tiny, peasant country — and failed. When the United States fought in Vietnam, it was organized modern technology versus organized human beings, and the human beings won. (171)

This is the very point which Ginsberg repeatedly stresses in 1966, only two years into the conflict, and while he accomplishes much by consistent concrete references to the landscape through which he passes, he likewise universally contrasts human flesh with the weapons used to destroy it:

Napalm and black clouds emerging in newsprint

Flesh soft as a Kansas girl’s

ripped open by metal explosion — (121)

Clearly, even those at home fail to escape the psychological and physical toll. War waged elsewhere returns. Numerical abstractions merely seek to conceal this fact. This is a world in which dreams are purposely turned into nightmares. Meanwhile, real children and siblings are sent overseas to engage in ideological conflicts at the behest of those with wealth enough to allow their own brood to opt out.

And thus today we suffer the ghosts of Vietnam, one of whom is Robert McNamara. The missile launchers may no longer haunt the beaches of Key West, but McNamara has somehow managed to outlive many of his contemporaries, including Ginsberg. He resurfaces in 2003 in his own personal movie, The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara. Here he claims that nuclear war was averted, not only once, but several times through sheer luck, and that human reason has proven inadequate to the complexities of governing modern nations.

So what’s new, Bob? He tells us what we knew all along, and we are supposed to praise, one might suppose, his late blooming candor. Not surprisingly, he is still vilified, and the movie is both admired and criticized. Imagine Rumsfeld apologizing for mistakes made in Iraq forty years later. Suppose he chooses to recant his decision to condone torture as simply misguided, and then consider his theoretical apology in terms of Ginsberg’s reference to ‘MacNamara declining to speak public language’ (120). McNamara surfaces repeatedly throughout ‘Wichita Vortex Sutra,’ one of many:

Hawks swooping thru the newspapers

talons visible

wings outspread in the giant updraft of hot air

loosing their dry speech in the skies

over the Capitol (121)

and, according to Alexander Cockburn’s review in Counterpunch, ex-secretary McNamara continues to manipulate the facts:

The Gulf of Tonkin ‘attack’ prompted the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution in 1964, whereby Congress gave LBJ legal authority to prosecute and escalate the war in Vietnam. McNamara does some fancy footwork here, stating that there wasn’t any attack by North Vietnamese PT boats on the US destroyer Maddox on August 4, but that there had been such an attack on August 2. It shouldn’t have been beyond Morris’s powers to pull up a well-reported piece by Robert Scheer, published in the Los Angeles Times in April, 1985, establishing not only that the Maddox was attacked neither on August 2 nor 4 but that, beginning on the night of July 30, South Vietnamese navy personnel, US-trained and — equipped, ‘had begun conducting secret raids on targets in North Vietnam.’ As Scheer said, the North Vietnamese PT boats that approached the Maddox on August 2 were probably responding to that assault. (http://www.counterpunch.org/)

Both Cockburn and Ginsberg arrive at an agreement in that McNamara consistently undermines not only his own credibility, but that of government spokespersons in general. It is an understatement to claim that the credibility of such people remains today suspect. These people are liars. McNamara becomes Rumsfeld, and Rusk becomes Rice, and all of these people perpetuate genuine crimes against innocent civilians.

Ginsberg’s poem articulates a healthy condemnation of the United States’ government, and it does so by stealing meaningless jargon and then loading that same jargon with meaning. Obviously, the people and the corporately controlled government ceased long ago to be one and the same. Although Silliman accurately notes that ‘Ginsberg’s poem didn’t stop the war any more than Picasso’s Guernica halted the rise of fascism,’ this poem nevertheless establishes a measure of human value where that value is otherwise under attack. Ironically, we are today still under attack by those who falsely claim to represent and protect us. Even as these cynics continue to seek and promote propagandistic merits of living in a power museum, Ginsberg’s verbal act of civil disobedience smolders within each of us as an unrelenting necessity. Certainly, no singular poem or mural forces massive change, but such gestures participate in an overall movement of human (good) will, and this will here arises in defiance of cynicism and despair.

Nations as currently imagined are no longer viable. Although such considerations are beyond the scope of this essay, we can anyway assess the obscenity of missiles aimed into the sky and the quest for global dominance. Within this context, poetry serves neither as an exhibit in the power museum annex of ‘American Literature’ nor as a means to gain name recognition, but rather for the sake of poiesis. Byrd is correct to emphasize that “The ultimate goal [...] is, as Walt Whitman realized, for everyone to be a poet — that is to say, for everyone to language a world that provides orientation for the community” (29). Even or, perhaps, especially during drastic times, poetry spontaneously and perpetually emerges from a need to make something of substance relative to the privilege of being here on this planet; and thus poiesis persists in spite the bureaucratic effort to flush all that is fine about people down some corporate latrine.

Baudrillard, Jean. America. Trans. Chris Turner. New York: Verso, 1988.

Bettmann/ CORBIS. Awaiting Armageddon: How Americans Faced the Cuban Missile Crisis. George, Alice L. Chapel Hill: UNCP, 2003.

Byrd, Don. The Poetics of the Common Knowledge. Albany: SUNYP, 1994.

Cannell, Rogers S. Live: A Handbook of Survival in Nuclear Attack. Englewood Cliffs NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1962.

Carroll, Paul. “I Lift My Voice Aloud, / Make Mantra of American Language Now... / I Declare Here

the End of the War!” 1969. On the Poetry of Allen Ginsberg. Ed. Lewis Hyde. Ann Arbor: UMP, 1984. 292-313.

Cockburn, Alexander. “The Fog of Cop-Out: Robert McNamara 10, Errol Morris 0.” Counterpunch.

24/ 5 Jan 2004. 26 Apr 2004

http://www.counterpunch.org/cockburn01242004.html.

FBI. “In Our Files.” On the Poetry of Allen Ginsberg. Ed. Lewis Hyde. Ann Arbor:UMP, 1984. 244-5.

———. “Three Documents from Allen Ginsberg’s FBI File.” On the Poetry of Allen Ginsberg.

Ed. Lewis Hyde. Ann Arbor: UMP, 1984. 247-51.

The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara. Dir. Errol Morris. With

Robert McNamara. @radical Media Inc, 2003.

George, Alice L. Awaiting Armageddon: How Americans Faced the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Chapel Hill: UNCP, 2003.

Ginsberg, Allen. “Wichita Vortex Sutra.” Planet News. San Francisco: City Lights, 1968.

Nixon, Rob. ‘Our Tools of War, Turned Blindly Against Ourselves.’ The Chronicle of Higher Education 51.24 (2005): B7-B10. 21 Feb 2006 http://0-search.epnet.com.wncln.wncln.org/

wncln.org:80/ login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&an=16259284>.

Pound, Ezra. “Vortex.” Revolution of the Word: A New Gathering of American Avant Garde Poetry 1914-1945. Ed. Jerome Rothenberg. New York: Seabury P, 1974. 80-1.

Rusk, Dean. Interview. Face the Nation: 1963-1964 22 Mar 1964. New York: Holt, 1972. 159-65.

Scheer, Robert. ‘Vietnam: A Decade Later Cables, Accounts Declassified Tonkin — Dubious Premise

for a War.’ Los Angeles Times 29 April 1985: 21 Feb 2006 http://0-infoweb.newsbank.com/.

Silliman, Ron. “Tuesday, February 14, 2006.” Silliman’s Blog. 18 Feb 2006

http://ronsilliman.blogspot.com/2006/02/kent-johnson-after-sending-me-note-i.html.

X, Malcolm. The Twentieth Century: A People’s History. Zinn. New York: Harper Colophon, 1984. 160.

Zinn, Howard. The Twentieth Century: A People’s History. New York: Harper Colophon, 1984.

[1] Citations refer to page numbers.

[2] For purposes of citation, these claims come in the front matter and precede the page numbers.

Stephen Kirbach

Photo by Monica Fauble

Stephen Kirbach observes the decline of the sustainable ecosystem from the foot of Chicken Hill in Asheville NC US. Some of his poems can be found through a web search and, despite a preference for riding the bicycle, he thoroughly enjoys correspondence: stephenm AT main DOT nc DOT us