David Koehn reviews

Profane Halo

by Gillian Conoley

72 Pages, Verse Press, Paper, $13.00 ISBN: 0-9746353-2-4

This review is 4,200 words

or about 6 printed pages long

Deep reassembly

The title of the book Profane Halo comes from Giorgio Agamben. Agamben is a theoretician in the mold of Foucault. He calls attention to minor details of history such as the fact that the Fascists and the Nazis came about without ever changing their political state nor their respective socialist or democratic constitutions. Hmmm. The “profane halo” of Agamben is the “incorruptible fallenness” of characters in German short story writer Robert Walser ‘s book The Coming Community.

I like what Conoley has to say about characters of such ignorance, that not only do they “not look to fulfill some theological purpose, they wouldn’t even know what a theological purpose is.” Things that live of themselves for themselves without the foreknowledge of purpose are living their purpose purely. For the title of a book of poetry it is both a wonderfully emotive and intellectual sentiment.

When reading Profane Halo, more than anything, I feel my mind stretch toward the airiness of the details of these poems. The intonations seem common, and the syntaxes familiar. For the poetic eye of Conoley is so displaced and odd that if the lexical structures weren’t mildly familiar most readers would struggle. But the understated quality of all the unique imagery and specific flourishes grants me just enough of the ephemeral subtext to make a go at each and every poem.

What a fine line to walk! Conoley lives at the edge of constant risk, at the precipice of disenfranchising and alienating her readers, and yet, to my ear, she never does.

In Conoley’s work the reader gets snapshots and clips of frameworks: a snippet of conversation as the label for an aging Polaroid that is the facsimile of the actual. Here is what I mean from a quick survey of the book’s title poem ‘Profane Halo.’ We have the “Huntsman in the quietened alley / / in the dark arched door . / / Train long and harpiethroated. / / Earth’s occasional moonlessness” and so forth. The “dark arched door” and the “moonless” earth provide the images of what I see as Conoley’s profane halos.

Presences in these poems, like the huntsman, inhabit a world as described in ‘The River Replaces’ where “The heaven is without description. / / Put them in one and the old will rage in a canoe. / / Heaven was splashes of color / / tossed casually from ecstasy to mania.” In ‘Sunday Morning’ the day falls apart in a way suggesting that entropy is order of highest importance, as “Thermiomorphic clouds color of sweet milk-cast shade in darkest suit. / / Idolatry, a man whacking at weeds / then a young girl lips to the dusty screen door / / longing for the neighbor child, leaves falling into sequence not category.”

And this is how humanity is formed in Conoley’s Profane Halo as if humans and their remnants, such as photographs, were but kicked up clouds of dust under the hoof of an unknowing universe trotting along.

In ‘Fatherless Afternoon’ a white birch tree is unable to paint a fence, the tree is “grazing the picket fence, / / yellow smearing blue across the palette, white spackled / / into sky over river / over upside down chair bobbing up / from the river.” The tree cannot paint the world this way, the resonance here is the upside-down chair. Clearly articulated for the desolate beauty it inspires, half sad, half grotesque, half comic — it doesn’t seem to add up at first, but only at first.

The poems here turn corners unexpectedly. The poems manage to stay just enough ahead of themselves — for they have to predict how closely the reader is to their lyrical leanings as they pull away and retreat and then hinge. At the end of the poem ‘Next and the Corner’ the anthropomorphized fence speaks. I’m not sure I can use anthropomorphic in reference to Conoley’s poems. In her aesthetic that would imply a superior consciousness of man over the consciousness of things.

In Conoley it is the casual universe that happens to give consciousness to one thing or another at any given time. Here we have the “Fence to the fencpost, / you be lost, you be contained” as if because the fence is tacked to the fencepost it is lost. That being contained is a false form, and such economic plottings have disenfranchised the meaning of border, or territory, or limit.

As we have at the end of ‘Burnt City’, the poems make “… syllabary hung / / like wash, sun mortal beautiful because it can destroy / / historical time.” Unfastened from the linear, the desperation and observation find a way to settle into being, a being that wants to deconstruct the aspect of the world that interferes with its natural chaos. In Conoley this is its elegance and beauty and organizing principal. A place with “Unsullied white flowers / / of form and the form of darksome cloud / / pine lanes and the fresh horses who fly into them, / / fly through them, fly in.”

I can go on but at this point I’d like to turn to a specific poem in the book, ‘Birdman’, and look analyze it in detail. The fifteenth poem in the book, a poem of 31 lines, a poem that employs a wide variety of Conoley’s mechanisms.

Though not presented on the pages as such, the poem, Birdman, manages its utterances as a poem of couplets, and pairings, and chirpings. The call response of line into line creates an ascent of sounds and rhythms and images. The ascent here swirls around the making and unmaking of understanding. The poem tries to expose, however oddly, what the Birdman means to the speaker and to the world.

Birdman

I feel this tragic figure sitting on me

as stars dot to dot over the water that is potable.

As shoeblack in the hair will defoliate the scalp.

As lyric, lyric, cries the verb, speaking of the thing.

(As the lawyer looks around for an ashtray.)

The ferry’s arc the ferry’s lamp

the inchoate sumac the inchoate sumac’s blonde wig

tossed casually now above the rocks.

City as the merciful end of perspective,

city as.

He said may we talk briefly so that God can be glimpsed

and alongside human conversation.

Heron. Hilarity. Time,

hilarious white spoonbill that cannot be held in the mind.

Erotic ripple marks on the shore

failing to prove one’s presence,

my halting attempt in the gusting spray.

Yes, sir. Yellow pine.

Some are more released by words. For some hell is other people.

He wears a green eyeshade cap, like an aging umpire,

in January 1943 issue of American Canary.

Title: “I wonder.”

He spoke for the pillars, the bars, the sea air, the perpendicular pronoun,

the little gods running around the rocks with small black cameras.

Sometimes I too felt like a motherless

says the lawyer,

neural damage, agrees

the doctor, each to each and in their horrible penmanship.

And nature does not abhor.

Once I was a House Sparrow

now I am a Yellow Hammer.

Poems like these of Conoley’s have a suggestiveness that implies a vague narrative that one can build a lyrical argument around. Despite the invisible aspects of their gleanings, the poems manage to associate just well enough to carry a clear emotion and some specific meaning as they dart and dash across the page. The danger of the kind of poems we find in Conoley is that the reader says “Oh how pretty” as a disguise for “I don’t what the hell that is all about.” The other danger is that they make even intelligent readers feel stupid. I hope to explore how a reader of Conoley might avoid these pitfalls… these dangers.

At the outset of Birdman, the speaker feels the presence of a tragic figure from the past perched on a shoulder like a small bird. There is a dread here. Though stylistically we are talking about dramatically different poets, the undercurrent of Larkin’s ‘Toads’ is at work here, the “toad work squatting” on one’s life. The difference is that with Birdman this sentiment has been twisted into aerials rather the dumped into squat pots. What toads are to Larkin, birds are to Conoley’s ‘Birdman’.

Also, we need to note that the word ‘Birdman’ reminds most readers of the “Birdman of Alcatraz.” In some way between the title and the first line we are set up to believe the speaker will provide some riff on this tragic figure, this “Birdman.” [Alcatraz prisoner Robert Stroud, subject of the 1962 movie starring Burt Lancaster, based on a 1955 biography of Stroud by Thomas E. Gaddis.]

The second line “as stars dot to dot over the water that is potable” provides as much of a setting as we are going to get from Conoley. Stars equal night. Potable water equals campsight, creek, spring? I think it nice that the stars “dot to dot.” This is their action. As an action verb, how strange. How peculiar. Yet even my youngest daughter would not struggle with the phrasing. It is, above all else, clear. Also, keep in mind that Alcatraz, the prison, was shut down partly because the lack of potable water on the island made it too expensive to operate, as well as because salt water corrosion had eaten the buildings away.

The “tragic figure” remains “sitting” and in Conoley endurance of time is something these poems hesitate to have patience with, for the figure remains sitting “As shoeblack in the hair will defoliate the scalp.” How can I make sense of this? My initial feeling is that it is nonsense but suddenly that sense-making organ that is my brain suggests that we are talking about the way night, “shoeblack,” full of stars, will make our hair stand on end, “defoliate the scalp” and feel as if our hair is falling out. Also, “shoeblack in the hair” seems to refers to the habit escaped convicts would have of applying shoe polish to their hair for an immediate disguise ( I think in the 60s TV show The Fugitive, David Janssen does this during the opening shots of each program).

On the other hand, perhaps it is a fact that if you put black shoe polish in your hair, your hair will fall out. Perhaps this tragic figure is like time, as time encroaches on us and as a symbol of time, our hair falls out. Perhaps this tragic figure is a signifier of time itself. When I think of the Birdman of Alcatraz, I think of a prisoner “doing time.” Is this important here? I can’t tell but don’t want to rule it out.

And then we get a third “as” in the fourth line, “As lyric, lyric cries the verb, speaking of the thing.” The first two lines of the poem work as coupling of set and reset. The third and fourth lines work in the same way. The “lyric, lyric” is the call of a bird, but it is also the call of the poem as if it were a bird through its “verb.” It’s “dot to dot.”

The poem leaps again, “(as the lawyer looks around for an ashtray.)” This nonsequitur begins to populate the poem with folks other than the speaker. What’s funny here, is that we have been placed out of doors. Under stars. Yet, out of habit, a smoking lawyer looks for an ashtray. He has been smoking, consuming time.

Also, when I think of prisoners, I can’t help but think of lawyers. Maybe a condition of too much prime time TV. This parenthetical lawyer suggests that I am supposed to be thinking about this Birdman as a prisoner.

Either on a lake or at sea beyond the creek’s “potable water” the poem leaps to “The ferry’s arc the ferry’s lamp.” The poem attends to the passing boats “arc’ as illustrated by the line in the night created by its lamp. This line is another chirping in the poem. A “lyric, lyric” call response of “ferry’s arc” and then “ferry’s lamp.” Now, I am almost certain we are in the scope of the island of Alcatraz, watching it if not on it; ferries are common on San Francisco Bay.

Immediately in the next line we get the flora of the scape in “the inchoate sumac the inchoate sumac’s blonde wig” that not only adds flora but suggests irritability with sumac’s connation of poison sumac. Plus the ball-shaped cluster of Sumac flowers have the shape of Victorian wig. Also, Sumac is a pioneer plant that depends on birds to spread its seed.

The repetition of “sumac” here provides another call response from inside the poem. Isn’t an itch, a kind of call response? We feel an itch, we scratch it. Isn’t the act of scratching almost always a back and forth of the fingers? Never just nails forward, always nails forward and then back, forward and then back.

Here the sumac is “tossed casually” as if it has been pulled and thrown away for a clearing. “Above the rocks,” provides more certainty to the poem. We are at the edge of a body of water, perhaps a river lined with rocks. Perhaps a river floating into a bay? A ferry is the type of boat that haunts a harbor. So I think we can consider ourselves well placed on our shoreline, amongst shorebirds, stars, and even a smoking lawyer.

Another leap. We must add to our accrual a “City as the merciful end of perspective.” This makes me laugh a little. Situated on our shoreline with a city in the distance and a ferry between, the inside joke of the poem about the “merciful end of perspective” suggests that it is aware, just ahead of us, that the reader has been trying to figure out the setting, the literal and figurative point of view in the poem. Its literal and figurative perspective: our Birdman’s view of the world from Alcatraz.

But even the line “City as the merciful end of perspective” is but a call to the next lines, seemingly obligatory response of “city as.” Another “as” that posits the machinery of “as” as the primary syntactical strategy in the poem. Part of its call if you will.

Now the reader is introduced to a new character in the poem. Is this person the lawyer? A new person? If it is a new character, who is he? The poem continues, “He said may we talk briefly so that God can be glimpsed / / and alongside human conversation.” Despite the strangeness of the phrasing that populates every poem of Conoley’s, usually to interesting effect — the person speaking seems to be saying on one hand lets talk, and on the other suggests that this time is not a good time to talk. This suggests that the scape is a place where one might glimpse God if one was not so busy in conversation. In conversation with the Lawyer? I don’t know. Again, these two lines work forward and backward in a way that they give meaning and take back meaning from each other. Another pair of call-response lines.

In the next two lines we get another pairing of “Heron” and “spoonbill” of “time” and “mind.” The poem continues, “Heron. Hilarity. Time, / / hilarious white spoonbill that cannot be held in the mind.” Heron’s inhabit much of the coastal United States but spoonbills do not.

While spoonbills were of no amount of endless hilarity to the Bronte sisters as they loved to study Bewicks’s History of British Birds — they appear only on the Gulf Coast. Perhaps time is a spoonbill, a bird one might be able to describe but be unable to hold in one’s imagination for very long. Perhaps not only did a heron humorously alight in the scape but a spoonbill did as well. Even more likely is that the idea or description of a spoonbill sounds absurd — hard to imagine.

If the reader’s mind can hold both possibilities, all the better. Isn’t laughter a kind of call response? One does not laugh with a “ha” but rather with a “ha ha”: the first guffaw a call for the response of the second.

As the poem continues, the speaker remarks the sand of the edge, as “erotic ripple marks on shore / / failing to prove one’s presence.” The striations in the sand fail to prove the presence of the self or of an ambient God?

Then the speaker makes an appearance, giving a “halting attempt in the gusting spray.” The speaker is about to speak in a voice subject to the winds that are gusting the ocean’s spray. The speaker says, “Yes, sir. Yellow pine.” The speaker is letting the “he” in the poem know that his request has been heard. But also trying to be recognized. Standing around and admiring the sand will not make the speaker be seen by him. Aren’t waves a kind of call response, break and pull? Isn’t conversation, a kind of call response?

So the speaker, speaks up. The speaker’s “Yellow pine” is an answer to a question. Is the question, “do you know what kind of tree this is?” And the speaker’s answer is that it was the large, crowned, straight-trunked, Pinus ponderosa, the ponderosa or yellow pine. Maybe. “Yellow pine” is found throughout the west. Lewis and Clark first took note of this pine as they found themselves looking to make their way down river in canoes made of Yellow Pine from their “Canoe Camp” in Idaho.

Was the question, “Are you from around here?” or maybe “Where are you from?” And the speaker’s answer, briefly, was “Yellow pine.” As in Yellow Pine, Alabama, population 648. We get a sense of the age of the speaker here as well. The “Yes, sir” seems to suggest a young adult deferring to an adult. Is this person a tourist eyeing the sites?

This young adult, does not want to say much, for “Some are released by words. For some hell is other people.” We are also connected again, I think, to prisoners. Sartre is lurking here, with his existentialism, and his “hell is other people.” We are not in the realm of the romantic by any stretch. The imprisoned are of a world where other people are hell. Prisoners in a world where language, or the use of it in conversation, is like a hell or a prison. The poem’s chirp, chirp can be heard here again. The speaker seems to suggest that speech does not appeal.

The speaker further observes this character, as “he wears a green eyeshade cap, like an aging umpire, / / in January 1943 issue of American Canary.” The speaker knows this character from reading a magazine article. The title of the article provides that slight tilt to the reading of the poem. The line, “Title: ‘I Wonder.’” Suggests the speaker is more than highlighting the title. The speaker was affected by the article.

My personal issue of the January, 1943 issue of American Canary has an illustration of the Linnet and Goldfinch done by N.E.R. Carter. Includes a full page ad for one to join the war time Navy (during war time). And it has an article in it by Robert Stroud, The Birdman of Alcatraz entitled, I Wonder. The essay begins:

Probably every man and woman who has ever dedicated himself or herself to a worthy task has sooner or later reached the place where it was necessary to ask and answer the questions “Am I a fool? Is this thing to which I have given myself and so much of my time and effort really of importance and value, or am I simply deluding myself, fretting away my life in the service of those who do not wish to be served?” Having reached that point in my own life, I have decided to put the question fairly and frankly up to you.

Stroud’s affection for Canaries was unsurpassed. This essay was a prelude to the release of his tome Stroud’s Digest on the Diseases of Birds. To fully gather this Seattle-born man’s story of trouble, his two murders, imprisonment, and ultimately his salvation in his birds, do read his story. The best site I have found on Stroud is here: http:/ / www.crimelibrary.com/ notorious_murders/ famous/ stroud/ index.html?sect=7.

What is it about birds that make us feel slightly more human, and more humane?

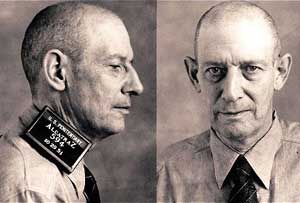

Robert Stroud, 1951

From: http://www.alcatrazhistory.com/stroud.htm

The poem continues with a snippet of commentary about the essay, “He spoke for the pillars, the bars, the sea air, the perpendicular pronoun, / / the little gods running around the rocks with small black cameras.” So without hesitation I think the poem’s applause of Stroud is how his essay, maybe even all his writing, expressed his imprisonment with its “bars” open to the tantalizing “sea air.” The pillars and bars and the letter I (the “perpendicular pronoun”) all seem expressive of the irony of his affections. All of that echoed into, and suggestive of, the “little gods.” I suspect the “little gods” are tourists, maybe even children, snapping photos, but the way they are presented here they seem observed like a scattering of shorebirds.

The article also mentions a period when all of Stroud’s canaries became very sick and he appealed “frantically to Government and State laboratories for assistance.” He received many letters that indicated those he thought might know remedies did not. He soon realized that “bird science, as a science, simply did not exist.” This inspired him and forced him to depend only on himself. He studied everything from histology to bacteriology and eventually cured his birds. Out of this struggle against the diseases of the birds that he kept in his cell came his digest on bird diseases.

So as a reader when I encounter the lines, “Sometimes I too felt like a motherless / / says the lawyer, / / neural damage, agrees / / the doctor, each to each and in their horrible penmanship.” I think the poem is suggesting the speaker and those who encounter Stroud’s struggle sympathize with him but can’t really understand what is needed. The lawyer’s “motherless” and the doctor’s “neural damage” all seem miscalculated assumptions handwritten in letters to Stroud about his birds. Even Stroud documents the overwhelming amount of correspondence he had received.

In Conoley’s poem we get a response to the call of, what is the quote from Thoreau? Nature abhors a vacuum? Conoley writes, “Nature does not abhor” in an implied response to Thoreau’s assertion. Ah, the full quote, “Nature abhors a vacuum, and if I can only walk with sufficient carelessness I am sure to be filled.” Here we see the imposition of the poet: the insistence that Thoreau’s assertion is anthropomorphic and therefore uncalled for. Nature is not so tidy as to only flood emptiness with meaning when there are so many other options. Still, the poem then asserts a transformation that seems to have arisen from just such a circumstance.

The House Sparrow is an interesting little bird. The North American population of the House Sparrow comes in its entirety from the birds released in New York City’s Central Park in 1850. It has adapted and now colonized virtually every environment on the whole continent: a strikingly pioneering bird.

The Yellow Hammer or as it is also known, The Northern Flicker. It is also known as the Golden Winged Woodpecker, the High-holder, and Pique-bois jaune by the French settlers in Louisiana. Having been a temporary southern boy, I notice that it is also the state bird of Alabama.

So here the statement, “Once I was a House Sparrow / / now I am a Yellow Hammer.” Seems to suggest how, through Stroud, our speaker has come to terms with their own transformation. A transformation from a common settler to a bird of a more particular heritage. A heritage somehow connected to our Birdman, Robert Stroud, caged on the island of Alcatraz. A heritage that somehow can make sense of Yellow Pine, Alabama and the San Francisco, Bay area. A heritage that understands imprisonment but also understands transformation from murderer to savior of birds, from a common House Sparrow to the striking, noisy, state bird of Alabama, the Yellow Hammer.

To close, I’ve tried to orient myself to Conoley’s Birdman by supplying as much context to give the poem meaning for me. I think for many, much less context will be required. I also believe for others this context is required but some readers will be reluctant to work very hard to provide it.

The pleasures in Conoley based on my experience with Profane Halo and with Birdman are that they are pleasures of superficial flight and fancy and with deep reassembly — a reverse effect. These types of poems may not meet the requirements of many readers. Even I seem to have a limited tolerance. That said, this poem, ‘Birdman’ engaged me in a process of deep consideration I found quite wonderful. Throughout Conoley’s Profane Halo such pleasures abound.

http://greatamericanpinup.blogspot.com/2005/04/usf-poetry-festival-2005-closing_19.html

it is made available here without charge for personal use only, and it may not be

stored, displayed, published, reproduced, or used for any other purpose

This material is copyright © David Koehn and Jacket magazine 2006

The Internet address of this page is

http://jacketmagazine.com/29/koehn-conoley.html