Michael Palmer

Ground Work:

on Robert Duncan

This piece is 3,200 words or about 5 printed pages long. It is the Introduction to a combined edition of Robert Duncan’s Ground Work: Before the War, and Ground Work II: In the Dark, to be published by New Directions in April 2006.

The story is well-known in poetry circles: around 1968, disgusted by his difficulties with publishers and by what he perceived as the careerist strategies of many poets, Duncan vowed not to publish a new collection for fifteen years. (There would be chapbooks along the way.) He felt that this decision would free him to listen to the demands of his (supremely demanding) poetics and would liberate the architecture of his work from all compromised considerations.

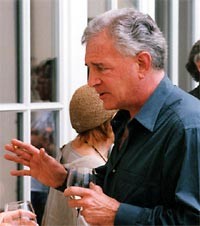

Robert Duncan, San Francisco, 1985, photo by John Tranter

He would allow the grand design (“grand collage,” Bending the Bow vii) to emerge in its own time from the agonistic dance of Eros and Thanatos, chaos and form, darkness and light, permission and obligation. It was not until 1984 that Ground Work I: Before the War appeared, to be followed in February 1988, the month of his death, by Ground Work II: In the Dark.

Together, the volumes offer a complex record of Duncan’s intellectual, aesthetic and emotional concerns during those often turbulent years, even as they trace his effort to conjoin the personal with the political, the immediate with the eternal, and to make a space capacious enough for the myriad contending presences within his art. Much of the drama of these two volumes lies in this quest to discover an “open form” sufficiently responsive to what is, essentially, an ungovernable vision. On the face of it, the task is impossible, as with any quest, or with any poem that chooses to manifest, perhaps even celebrate, the incommunicability at the heart of things. During these two decades, Duncan would commit himself to a vatic, daedal opposition to the Vietnam war, resulting eventually in the break-up of his deep and prolonged friendship with Denise Levertov, whose opposition was of a different order; he would discover the surviving members of his birth family; and he would receive news of his ultimately fatal illness.

Duncan was a legendary talker or word-spinner. Any given conversation might weave its way through Freud and the Zohar, Nietzsche and the Gnostics, the Albigenses, the Mabinogian, anarchism, the Tibetan Book of the Dead, Dante, Pound, Stein and H.D., Helen Adam, Piaget and Melanie Klein, Alfred North Whitehead, Dark Shadows (the campy, afternoon Gothic television soap he and Jess enjoyed), the Oz books, Renoir’s late, fleshy nudes, George Herriman, George Herms, George MacDonald, Homeric prosody, Zukofsky and Creeley, Stravinsky, Mahler’s lieder, Mahler’s correspondence with Freud, those recent recordings of the Bach cantatas, independent film (Brakhage, Kenneth Anger, Maya Deren, et al), new dance, the latest generation of poets, new painting, new music, and that sale on halibut fillets over in the East Bay (frozen, but anyhow). Such conversation was often joyous, always intensely vital, yet often also marked by an undercurrent of unquiet desperation. Electric connections would occur or fail to occur. The process was strikingly heuristic, resistant to closure, the goal a mapping of attention and a form of comprehension. It could be argued that a not dissimilar associative mechanism is frequently operative in the poems, but ruled there by what Duncan referred to as the Laws of Form, that obligation to attend to the harmonies and disharmonies of specifically poetic thought, thought engaged in a process of discovery, guided by measures both historically resonant and immediate to speech. Twin lenses: the eternal and the instant, each in Duncan’s mind focused upon, and focusing, the other, a (perhaps unobtainable) gnosis, or understanding, the desired end. Yet the end is elusive, even acknowledged at many points as illusionary.

Before the War: the various meanings of this phrase are crucial to an initial comprehension of Volume I. Readers were naturally perplexed by the title, as Duncan meant them to be. Why “before” when this work was appearing during the war and was so evidently immersed in its issues? In Duncan’s order of things, as citizens we are placed as witnesses before the war itself, in this case Vietnam, with its attendant lies, deceptions, profiteering, massive, murderous violence and tragic miscalculations. Dantean polysemy (“Letter to Can Grande”) is at work however. The war, all war, also always implies for Duncan the eternal, dialectical contention between creation and decreation, light and dark, form and void, being and non-being. Within the poet’s psyche, the creative imagination struggles endlessly to manifest itself, and by that, paradoxically, to transcend the limits of self, to obliterate self, to become other. To Duncan then, work of the imagination involves a form of psych-osis, a standing outside the boundaries, and a sort of madness. Ec-stasis would offer the brighter image of this state, and for Duncan both terms are operative. Forces formed within the Ego (that is the “Ich,” the “I”) must be channeled toward the obliteration (or else positive overcoming) of that “I” or self. In addition, this “before” implies that war is an eternal condition of human nature. War will follow war, within and without. Any opposition to the immediate war must acknowledge its various meanings, the forms of contention that for Duncan are also the source of poesis, poetic making and meaning. The poet is everywhere implicated in such human and metaphysical circumstances. He or she cannot stand apart or above. The poem itself cannot preach without betraying its nature; it must enact. Here we come to the painful rupture between Duncan and Levertov. For Duncan, the poet and the poem have no grounds for self-righteousness. Political engagement must not deny the complex and contradictory forces of the poem’s voice as it comes into being and voices the multiple aspects of human desire. The poem’s “message” as such must not be manipulated or predetermined, which for Duncan would imply an essential betrayal of the poetic act, of poetic listening. Yet this demand leads to a classic quandary. How make a space for both personal poetic intention and that of the poem? Duncan’s solution lies in part in an ever-greater openness of form, in the hope that all vectors of poetic thought may find their place in the poem’s field. His Passages sequence, taken up again in these two volumes, offers perhaps the most radical example of this poetics. It certainly contains his most Poundian verses. Poetic form is stretched almost to the point of dissolution. The poem-as-object yields to the exigencies of process. Such a potential impasse, between the immediate and the eternal, also reminds us of Duncan’s concept of myth as “the story that cannot be told.”

Homages, derivations, imitations: Ground Work I: Before the War forms a kind of echo chamber, where song circulates across time, as Duncan pays tribute to the many voices that constitute his own and which, assembled, fashion the “other voice” of poetry, the antinomian stream beneath the tides of history. In the “Dante Études,” Duncan’s poetry occurs in counterpoint to passages from such works as Dante’s De Vulgari Eloquentia, De Monarchia, and the Convivio. As outlined in his preface, he hopes to celebrate the immediacy of Dante to his own poetics and, through the lens of his work, to reflect — musically — on the poetic and political orders of our troubled times, and at the same time “to unfold the secrets of the heart.” The outer and the inner worlds are not to be distinguished; the truths of one enfold and amplify those of the other:

My whole life

needs to be here

to come alive

in this consideration.

There is an intimate and, as Nathaniel Mackey notes in “Uroboros: Robert Duncan’s Dante and A Seventeenth Century Suite,” almost confessional character to much of this work. Duncan’s “Homage to the Metaphysical Genius in English Poetry,” quoting and invoking Ralegh, Southwell, Herbert, Jonson, and the neo-platonist John Norris of Bemerton couldn’t be farther from T. S. Eliot’s coolly authoritative and seemingly detached examination of writings from the same period. Even as the exploratory forms of modernism deeply inflect these works, an intimate, romantic immediacy has been reintroduced. It is an immediacy both fervent and desperate in its effort to capture a moment of atemporal transmission, exchange, circulation. What we arrive at is an ardent contact between voices across time, a conversation about life experience, artistic imagination, eternal bafflement, in which each text is altered by the presence of the other. I doubt whether many of my generation, for example, could experience Duncan’s invocation of Southwell’s Burning Babe without conjuring the horrifying photograph of the young Vietnamese girl, Kim Phue Phan Thi, burned by napalm and fleeing naked down a road. Yet caution is necessary here. The poem is in fact a response to Levertov’s “Advent 1966,” which Duncan first received by mail from Levertov in December of 1966. There, the parallel with the napalmed children is explicitly and directly asserted. For Duncan, inevitably, the image is multi-dimensional, acquiring an eternal, existential and spiritualist resonance. It is not so much a rebuke, at this point, of Levertov’s poem, as a commentary and response from another perspective. In hindsight, though, it is instructive in regard to the unbridgeable gulf that would eventually open between them:

This is not a baby on fire but a babe of fire,

flesh burning with its own flame, not toward death

but alive with flame, suffering its self

the heat of the heart the rose was hearth of;

Duncan will identify with this image as mirror of the drama of the self’s necessary struggle and undoing in pursuit of the imagination’s Art, its end. It is a theme powerfully voiced in Volume I, one that will be taken towards its limit in Volume II. Present in some form from the time of Duncan’s earliest works, it now reaches full resonance with his premonitions of approaching death. The “nothing” of dissolution, of course, is a necessary part of the mythic cycle that the poet, in Duncan’s syncretic cosmology, is obligated to embrace and enact.

In that regard, let me briefly draw attention to what seems to me one of the finest achievements in Volume I, a masterpiece of elegy, circularity and negative lyricism, “A Song from the Structures of Rime Ringing As the Poet Paul Celan Sings.” The “I” singing is at once Duncan/ Celan, if not some First Person beyond them both. A wrecked world has brought him to wreckage, to nothing; from his wreckage, the world “returns / to restore me...” The nothing the poet comes to, the grief of necessary knowledge, is also what causes him to be in the fullest sense. The movement is cyclical and unending, without closure or resolution, and the poem mirrors this in its irresolvability, its dwelling (much like one of Duncan’s most frequently cited poems, “Often I Am Permitted to Return to a Meadow”) in paradox. I hasten to add that the “likeness” Duncan discovers is by no means a presumptive identification with Celan’s actual life-experience, its origins in the horrors of Shoah. The likeness or sympathy is realized in the ground of poetry itself and its recognitions or acknowledgements.

Before the War opens with the solitary voice of Achilles, lost in the vastness of the sea and its voices calling upon him to return to himself. What “vehicle” will be sufficient for this? Troy (and his death) long past, he has returned home to homelessness, among “the mothering tides.” Thetis, then, and the sea, what guidance can they offer in the face “of an old longing” whose spell still consumes him? Is it the enchantment of the spell itself, or the remembered rhythms of war (and “the deeper unsatisfied war beneath / and behind the declared war”), or some unquiet memory, unresolved desire? With its specific mythic imagery and irresolvable questions, the poem clearly represents a deeply felt acknowledgement of Duncan’s debt to H.D., in particular her Helen in Egypt.

The volume closes, by contrast, with the sometimes ecstatic, devotional “Circulations of the Song,” in homage to Rumi. “Song” is found in the titles at the start and finish of the book, reminding us that whatever the necessary fractures, dislocations and violent, declamatory upswellings, the lyric impulse drives the vision of the whole. Against the earthly tyrannies and the “cloud of lies,” there is the realized experience of poetic company and domestic companionship, and there is the confirmation of a poetics of desire through the mystical ghazals of Rumi. The poem celebrates the long partnership with Duncan’s companion, the painter and collagist Jess, even as it speaks, once again, of “falling into an emptiness of Me...” The something and nothing conjoined alone render the entire truth of experience. The metaphor of the title stands as central to Duncan’s poetics of call and response, of a responding to the actual beyond the limits of the single, isolate voice. The poem is always in circulation among the poems, coming to life there.

In the fall of 1984, I believe it was, I received an excited phone call from Duncan. He had completed a new poem, the first fully achieved in the time since his kidneys had failed and he had been forced to submit to a debilitating regimen of dialysis, medication and dietary restrictions. Might he come by and read it aloud, to see whether it was the real thing? Of course. The poem, “After a Long Illness,” was indeed “the real thing” in its quiet rehearsal of what had come to pass during the years the toxins had incrementally altered Duncan’s internal and external life. It contains both a greeting to Jess, after Duncan’s hospitalization and near-death experience, and a tacit farewell. There is a measured calm, a reflectiveness about it as he looks back at the turbulent moods of recent years, the uncontrollable surgings of the blood, the upswellings of rage at many of those most close to him. A voice says, “I have given you a cat in the dark.” As Norman Finkelstein notes in his excellent, detailed study of Ground Work (“Late Duncan: From Poetry to Scripture”), this is a familiar, a presiding daemonic spirit attendant upon the work of the mage, a conduit between the various realms of image-gathering and understanding, and between the light and the dark. Its “magnetic purr” speaks and soothes. The poem would signal the completion of Ground Work II.

Robert Duncan and cat, 1985. Photo John Tranter

The volume ends with Thanatos presiding. It begins, by contrast, under the sign of Eros, “this dark of the sexual moon.” The sequence “An Alternate Life” tells of an affair with a younger man, undertaken during a trip to Australia, an affair that compels Duncan to acknowledge old age coming upon him. “New age” and “old youth” whirl together within him as he contemplates “the matter of Love” with “my own particular death in it.” It leads him, as so often in his work, back to an affirmation of his life’s enduring center in Jess’s domestic company, and of life’s brevity. The final stanzas, in their characteristic, tortuous syntax, fill with a certain foreboding, even as they celebrate “Love / that overtakes me and pervades the falling of the light.” We are reminded of the phrase, “in the dark.”

Like Volume I, Volume II is constructed, with a few exceptions, of sequences and summonings. There are the open sequences of Passages and the “Structures of Rime” that extend across the body of Duncan’s work, and the closed sequences, such as “To Master Baudelaire” and “Veil, Turbine, Cord & Bird,” the latter the fortuitous result of an exercise conducted while giving a workshop at the Naropa Institute. Baudelaire, Yeats, Rilke, Swift, Nietzsche, Mallarmé, Pound and Carlyle all appear as dark familiars in the work of poetry. “To Master Baudelaire” establishes the tone of malaise and infection that will prevail in much of what follows. “When I come to death’s customs, / to the surrender of my nativities...” He peers into the Baudelairean mirror to acknowledge that “Hatreds / as well as loves flowd thru as the / sap of me.” He summons the “Muse of Man’s Stupidities” and acknowledges “the endlessness / of a relentless distaste.” We are in the full atmosphere of Baudelaire’s “spleen.” He will reappear in one of the darkest and strangest of the Passages, “In Blood’s Domaine,” where the “Angel Syphilis” and the “Angel Cancer” preside over “the undoing of Mind’s rule in the brain” and where “cells of lives within life conspire.” We have arrived at the heart of darkness, where Form has been infected by “scarlet eruptions,” and where another language prevails.

Among the “exceptions” noted above is “The Sentinels,” a poem of intense, visionary lyricism that reminds us of the great dream songs in collections such as The Opening of the Field and Roots and Branches. It echoes an earlier, more self-contained mode, mostly submerged in Ground Work beneath the violent, polar forces at play. Elsewhere I have said of it, “The poem represents a descent into a crepuscular, wordless, near indiscernible world over which earth owls preside, as sentinels. It is a world of ‘after-light,’ a zone where waking and dream, conscious and unconscious uneasily meet, mingle and intertwine; a world of mute memory (‘silent as a family photograph’), ghosts and traces, through which the poet, himself wraithlike, passes, interrupting the silence with the scratching of his pen. The owl (should we think of Minerva’s owl?) is always the ‘bird of poetry’ in Duncan’s work, yet here, in this sequence of fragments or dream recollections, we have owls ‘clumpt’ ‘in ancient burrows’ in the earth, ‘so near to death,’ as if buried but not quite. Chthonic beings, they preside over an Orphic world the poet must enter to find the ‘secrets of the earth,’ that ‘owl-thought...hidden in all things.’ It is a placeless place, prior to language, from which the measures of the poem arise. From there the poet returns to the upper, waking world, harboring the figures and forms he has been given.” Its complex coherence reminds us of such epiphanic moments in Duncan’s work as “My Mother Would Be a Falconress,” and “A Dream of the End of the World,” where the different realms of imagined being, for all their psychic contention and violence, offer “counselings...hidden in all things.”

To work “in the dark,” to proceed by errancy in a dark wood, to allow the forces of reason and unreason to fully contend, runs against the grain of a serviceable poetic practice, too often content to offer up hors d’oeuvres of the scenic and sentimental. Duncan was prominent among a generation of poets who sought to recover poetry’s exploratory capacity from the strictures of orthodox critical propriety. Perhaps no one among his peers committed himself more profoundly to the magical, Orphic dimension of the poetic voice, and to the dynamic tension between the flowing currents of a restlessly associative mind and the demands of construction. To proceed in such a manner is to give yourself over to the poem, to be at the mercy of its figures. Both the costs and the rewards are evident here.

Michael Palmer, Berlin, 2001

photo by John Tranter

Michael Palmer was born in New York City in 1943. He is the author of numerous books of poetry, including Codes Appearing: Poems 1979-1988 (New Directions, 2001), The Promises of Glass (2000), Notes for Echo Lake (1981), The Circular Gates (1974), and Blake’s Newton (1972). His work has appeared in literary magazines such as Boundary 2, Berkeley Poetry Review, Sulfur, Conjunctions, and O-blek. Michael Palmer’s honors include two grants from the Literature Program of the National Endowment for the Arts and a Guggenheim Foundation fellowship. In 1999 he was elected a Chancellor of The Academy of American Poets. He lives in San Francisco.

it is made available here without charge for personal use only, and it may not be

stored, displayed, published, reproduced, or used for any other purpose

This material is copyright © Michael Palmer and Jacket magazine 2006

The Internet address of this page is

http://jacketmagazine.com/29/palmer-duncan.html