John Most reviews

The Burial of the Count of Orgaz & Other Poems

by Pablo Picasso

Edited with Introductions by Jerome Rothenberg & Pierre Joris, Afterword by Michel Leiris.

352 pages, US$19.95, ISBN 1-878972-36-7

Exact Change Publishers, 5 Brewster Street, Cambridge, MA 02138 USA; orders@exactchange.com; http://exactchange.com/

This review is 1,000 words

or about 3 printed pages long

Picasso As Poet

L: A ferocious cat, pregnant, holding the carcass of a bird in its teeth. After midnight, two men descend to the water to spear a fish or two. Two women, one with a bicycle, observe. An artichoke, a sheep’s skull, a rooster, a monument for the dead.

Y: Toledo, Spain. In the foreground, ahead of the entire drama, there is a young boy. He holds a torch with his left hand. With his right hand he points to the dead man, the Count of Orgaz. In his pocket, the name of the artist written on a rag.

R: from November 18, 1935: “a bouquet of fuck it all skyscrapers.”

C: Animism is not the right word.

G: The detractors will say, it’s repetitious, it’s as if the paintings have regurgitated poems. Look at word choice alone: guitar, harlequin, bull, dance. There is no poetic vision, no step forward. He has jumped into poetry naked, his only clothes having been painted on. The supporters will say, how beautiful. At the center, Picasso is just as much a poet as he is a painter. Yes. It is precisely when the lines rise above word and paint. That is when they come alive.

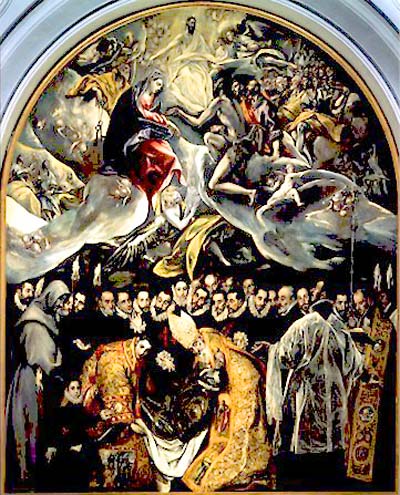

The Burial of the Count of Orgaz, by El Greco.

1586–88. Oil on canvas, 480 x 360 cm. Santo Tom233;, Toledo

A: Louis the Fifteenth pawned Zola’s personal computer. Velázquez hired Goya through an employment agency. To no surprise, the allusions are predominantly European, from Spain through Paris.

P: Supposedly, after Gertrude Stein read a poem by Paul Bowles, she told him he wasn’t even a bad poet, he was no poet at all. To a certain extent, I agree. Musicians, poets, and even painters are made differently. Different energies, different egos, different actions.

D: A five-year project. Jerome Rothenberg and Pierre Joris brought together several translators (David Ball, Paul Blackburn, Manuel Brito, Anselm Hollo, Robert Kelly, Suzanne Jill Levine, Ricardo Nirenberg, Diane Rothenberg, Cole Swenson, Anne Waldman, Jason Weiss, Mark Weiss, & Laura Wright) in order to bring Picasso’s Spanish and French poems to the English speaking world. And a final touch — an essay by Michel Leiris serves as an afterword.

F: His father was especially fond of pigeons: “the silver lace the pigeons raise up making light of their sad plight.”

I: To be human is to be animal, this tastes good, that smells bad, while holding the idea that everything is animated vis-à-vis humanity. When picked up by humans, inanimate and animate things become full of life, become interconnected in infinite ways. The point is not to say that this confusion is bad or good, for it is both. The point is to say I see this, I taste this, I feel this. That this, a bullfight, a chirizo, a dancer, can be beautiful, can be seen in a new way, in countless ways. At least that is what I hear in the poems.

N: Pablo Ruiz Picasso (1881–1973) died well before I was born.

H: Legend. A pious aristocrat died. Don Gonzalo Ruiz. During the funeral, the saints Augustine and Stephen descended to help with the burial. El Greco, or Domenicos Theotocopoulos, was commissioned to paint this event in 1586. The Burial of Count Orgaz.

J: André Breton wrote “Picasso poète” for Cahiers d’art in 1935. Instead of writing about “les jeux de l’ombre et de la lumière,” he should have written about the wrecklessness of poetry.

K: Some say the boy in El Greco’s painting is his son.

L: Jacques Lacan and Georges Braque watch Picasso’s play, Desire Caught by the Tail.

M: 1,000 drums. 2,346 clouds. 6,422 dancers.

S: For sure, El Greco was a branch in this artist’s genealogy. Yes, the death of the father allowed the boy to play freely, in any and every way imaginable. The funeral appears in Picasso’s poetry and in his art (see The Burial of Casagemas and Suite 347).

T: Within the prettiest moments a language chain is created that tangles and untangles itself effortlessly and repeatedly. It is not as simple as a paradox, controlled chaos, nor as complex as a sleight of hand, a language game for the sake of a language game. The connecting words allow you to hear life multiplying life, multiplicity in everyday things: “the pale rose colors its rose with rose that is paler still and the rose rosens with rose in the rosiest rose yet of the rose rose rosing its rose rose rose rose”

Q: I can read French. I cannot read Spanish. Today, in New York it feels like fifty-nine degrees. It is raining.

U: from April 12, 1936: “the bronze rubber erases at the four corners of the table of the set piece of the sagacious shadow collector of cries and folded orgies submissive to the play of light and the whims of drawing that the blinded groping sun complicates with its seeds”

O: Please see Paul Blackburn’s translation, Hunk of Skin, and read the plays as well.

W: A log, a diary, a journal as poetry. The normal characteristics: a list of tauromachian emblems, words from a newspaper, lines written while out of town or in transit (Antibes, Vallaurais, St. Tropez), day to day life.

X: The obvious roadblock. Canvas as page, page as canvas. An artist who happened to write poems or a poet who happened to be an artist. Irresolvable? This may or may not be a glaring problem. Argue it one way or the other. His connection with Eluard and Apollinaire. His artistic contributions to books of poetry. His portraits of Góngora, Mallarmé, and others. The poems dedicated to him and his work (Cocteau’s “Ode à Picasso” et cetera). All of this allowed the poet to come to life. It’s everything but unusual. Poetry as painting. There are a million examples. And yet. And yet the most beautiful aspect is also the largest obstacle. The painter, the sculptor, the art collector. So these words will eternally be handcuffed to the footnotes of Guernica or Les Demoiselles d’Avignon? I don’t know.

Z: from July 20, 1940: “the gypsy dancers in a cricket serenade the ears of owls on a dead end country lane a nape of kinky hair that slams the door of sunlight on the big bass drum the cymbals in a rain of feathers of all sorts of colors singing with loud screeches”

2006: New York City

John Most is a poet. He lives in rural Virginia and New York City

it is made available here without charge for personal use only, and it may not be

stored, displayed, published, reproduced, or used for any other purpose

This material is copyright © John Most and Jacket magazine 2006

The Internet address of this page is

http://jacketmagazine.com/30/most-picasso.html