[Note: This is an adaptation of presentations made at the College of William and Mary, 2004, and the Virginia Military Institute, 2005.

Because of the many photographs, this file may take a while to load fully.]

paragraph 1

We often think of photography as an individualistic, solitary art – a single man or woman working the alchemy of a dark room, or one with a frequently small sometimes large mostly metal object that has a magical, transforming effect on others before that little “click” is ever heard. We don’t usually speak of Annie Leibowitz and collaborators, of Alfred Eisenstadt and partners, of Robert Frank and co-workers in the writing of light.

2

But much of whatever I may have managed to do in photography involves, in a variety of ways, a debt to others – and wouldn’t have been possible without them. Let me begin early, over eighty years ago: my grandfather was a portrait photographer, shooting black and white 5 x 7 negatives (the prints were sometimes handtinted by my grandmother) of individuals, couples, and families, at his studio in Parkersburg, West Virginia. He shot family members; he shot himself in his 1926 Buick convertible; he made countless studio portraits of my mother, often in elaborate costume, sometimes with grand backgrounds, from the days she was a small child through later years.

3

But I never saw his studio or his equipment, for he’d retired, selling everything, by the time I came along. But his self-portrait, gazing at me through clear blue eyes, with round white collar and blue necktie and pin, sits just a few feet away from where I do much of my work today.

4

I grew up, in my grandfather’s last days, in Tokyo – first, Occupied Tokyo, after World War II; then, eventually, the economic miracle. Cameras were a given in such an environment, with a “DPE” sign (indicating a photography shop that features developing, printing, and enlarging) on virtually every neighborhood block.

5

And cameras were a given as well within our family, because not only of the influence of my grandfather but my father: living in China in the twenties and thirties, he’d photographed, in still and moving image, daily street scenes; visits to parks and temples; and my older brother and sister at play, their amas watching close. And though my father was less the avid photographer as I was growing, boyhood to adolescence, the role of cameras – in documenting family members, family events – remained near the core of our lives. Looking at some of our many snapshots from the 1950s alone, my wife once exclaimed, “You’re the most photographed family on earth!”

6

But as I remember, back in those days I myself wasn’t particularly involved in photography. With a few exceptions: around age fifteen, I brought my 35 millimeter Asahi Pentax to school, and took candid portraits of friends. I even had the nerve to bring it to English class and shoot our curvaceous instructor when she bent over the book at her desk, exposing more of her neckline – and got away with it. A year or so later, more serious-minded and ambitious, I was running for the vice-presidency of the student council at the American School in Japan. With my Pentax I shot our main corridor, jammed with students between classes; and again after school, utterly empty but for skeletal looking lockers lining the walls. At one of those DPE stores I had the shots blown up, and made a poster with the caption in block lettering, “ALL FOR BALL OR NONE AT ALL.” I contemplated a career in advertising, combining word and image.

7

But I didn’t think of myself as a photographer, and certainly had made no sort of commitment; in fact, a greater love, from about age eight, was movies. In spacious big-screened theaters with excellent projection we – first, with my mother or mother and father, later by myself or with friends – saw major American releases in the way movies were meant to be seen (There were even obliging ushers at the ready with discreet flashlights to guide you to your seats within the huge darkened cave of the theater.).

8

And that appetite for moving pictures was stimulated greatly when, back in the US in the mid-sixties, I began running my college film programs, and became especially interested in not only European narrative but contemporary independent avant garde works, and invited filmmaker Jonas Mekas to campus. Jonas brought with him a movie camera; I shot my first movies with the small, sturdy 8 millimeter Revere he placed in my hand. (Over time my interest in still and moving image alike proved not a mutually exclusive matter; one of my films, for example – “Enthusiasm” – consists entirely of stills, of purely photographic images accompanied by voiceover.)

9

After a year in New York working with Mekas and others my lady friend of those days and I hitchhiked crosscountry and into Mexico, where we lived several months in a tiny electricity-less village where the mountains and the jungle and the sea met. And where – entering the nearby larger town one day for supplies – we were arrested and jailed half a month. (Our arrests came without charge – it was apparently the semiannual day for a roundup of gringo hippies. Within the jail, I made a movie of the experience with my 8 millimeter Camex, which I managed to bring inside.) We were deported, and I began a new phase of my life, which connects with the photographs before you.

10

To begin chronologically, the first “Ginsberg & Beat Fellows” shot is of a group of seven men on a hillside – one in a straw hat, one in a beret, one in a red hat, one in a buckskin jacket. There are a couple of dogs, a couple of chickens.

11

This is one of the early ones of what became nearly a thousand shots of poet Allen Ginsberg and such colleagues as, here, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Gregory Corso, Peter Orlovsky, and Robert Creeley. It wouldn’t have been possible without a friend of mine in New York – Leslie Trumbull – who’d given me the Rolleicord with which it was taken.

Allen Ginsberg's Committee on Poetry, Inc. farm, Cherry Valley, New York, October 1969. From left, standing: Julius Orlovsky, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Gordon Ball, Allen Ginsberg, Robert Creeley. Front, seated: Gregory Corso, Peter Orlovsky.

12

The shot documents a period in my life which began on return to New York, when a friend, Barbara Rubin, told us she was helping Allen get a farm – a retreat for poets – in upstate New York, with the hope that we’d be caretakers. So this shot – taken on an October weekend 1969, a couple days before the death of Kerouac – and likely the many that followed would not have been possible without Barbara, too. But most of all, none would’ve been possible without Allen. I mean this in several ways.

13

For one thing, there was his willingness to be photographed. Not everyone, whether of great poetic gift and powerful political and spiritual prophecy or not, would be so adaptable in front of a camera. Of course, one might note that Allen loved the limelight, was a great ham, and so forth – but in picture after picture his countenance displays no cheap or vulgar affect. For example, in this hillside shot, he’s relaxed, casual, yet standing straight, looking with interest into the lens. I might add that to his left he’s elbow-to-elbow with Robert Creeley, an occasional visitor to the farm whom Allen greatly respected as poet (In fact, that respect seemed mutual.) And each seems careful to give the other space, to not get too chummy.

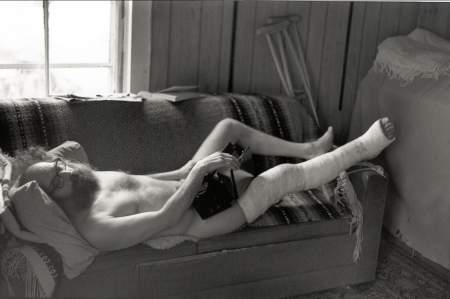

Broken-legged from slipping on icy flagstone in front of farmhouse, Allen sings Blake. Cherry Valley, March 1973. Photo Copyright © Gordon Ball, 2006

14

Three and a half years later, Ginsberg’s equally at ease naked on a couch singing Blake, cast from toe to thigh from a fall on one of the flagstones in front of our farmhouse.

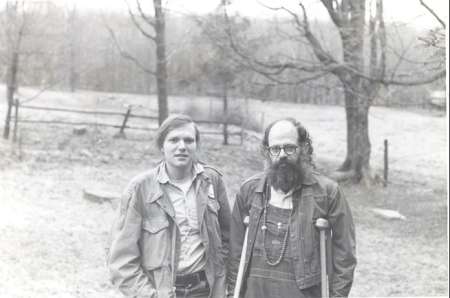

Allen Ginsberg (right) with Gordon Ball, photographed by Peter Orlovsky from front of farmhouse, facing meadow and woods-enclosed tarpaper shack of neighbor Ed "The Hermit." March 1973.

15

The next day he’s on his feet out of doors on crutches, as he and I – in a shot taken by Peter Orlovsky – stand side-by-side afront the same hillside as in the first photo.

Herbert Huncke, Allen Ginsberg, near window of Ginsberg’s E. 12th Street apartment, New Year’s 1976. Photo Copyright © Gordon Ball, 2006.

16

With one of his “sacred companions” – raconteur, junkie, conman & charmer Herbert Huncke – Allen looks patient, contemplative, and possibly burdened. It’s New Year’s 1976; their faces are lit by the wonderful low light of winter, crossed by shadows from the open blinds of Allen’s new apartment at 437 East 12th Street.

Allen Ginsberg, Philip Whalen, novelist William S. Burroughs, swimming pool area, Varsity Apartments, Boulder, Colorado, July 1976. Photo Copyright © Gordon Ball, 2006.

17

Half a year later we find Ginsberg with other Beat Fellows, poet Philip Whalen and novelist William S. Burroughs, in nothing but swimsuits and towels – a laugh-aloud picture for some when beholding it. Yet Allen, even here in “The Bathing Beauties,” maintains a sort of dignity of person – even as he holds a half-eaten apple! It was one summer afternoon, by the poolside at Varsity Apartments, Boulder, Colorado, where Naropa Institute faculty were housed. I took a small suite of photos of this scene.

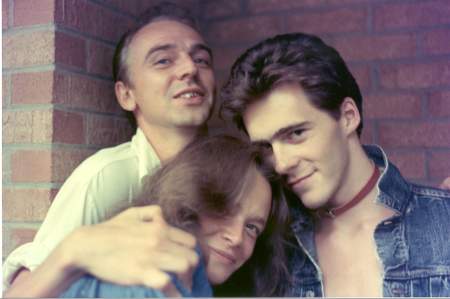

Rene Ricard (poet; art critic; actor in Andy Warhol's Chelsea Girls), poet and performance artist Anne Waldman, poet Steven Hall, Naropa Institute, Boulder, Colorado, July 1976. Photo Copyright © Gordon Ball, 2006.

18

The same summer – 1976 – three friends assume an aesthetic pyramid against Varsity’s brick walls: poet, art critic and actor (Warhol’s Chelsea Girls) Rene Ricard; poet Anne Waldman, co-director with Ginsberg of the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics at Naropa, and poet Steven Hall.

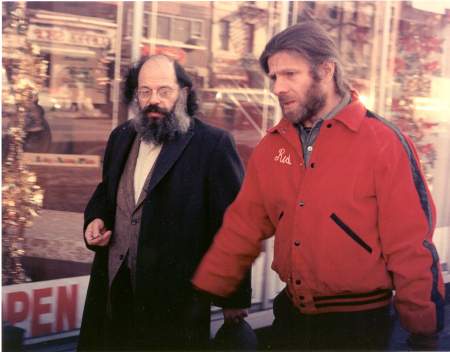

Allen Ginsberg, Peter Orlovsky, New Year 1977, New York City. Photo Copyright © Gordon Ball, 2006.

19

The next New Year’s, I’m back in New York for a stroll with Allen and Peter on First Avenue, possibly going to get keys copied. It’s a week after Christmas, with tinsel in a shop window still. Both companions wear clothes from the Salvation Army, where Allen loved to shop: his fine dark overcoat and possibly his sport coat; Peter’s high school style jacket with another’s name sewn on the right breast.

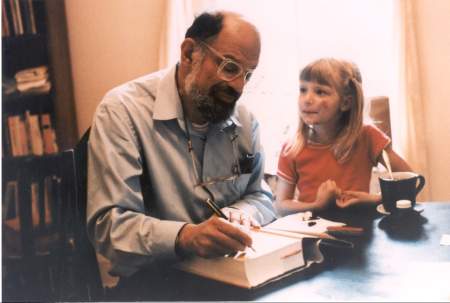

Allen Ginsberg autographs his Collected Poems for Daisy Ball, whose cheek was scratched in a roller-skating fall on May 31, 1986, Jackson, Mississippi. Photo Copyright © Gordon Ball, 2006.

20

Jumping nearly a decade – I married a woman I met in Carolina, finished grad school, we had a baby – Allen visits us in Jackson, Mississippi, following the American Book Association convention in New Orleans. Here with five-year-old Daisy, her cheek scratched from a rollerskating fall, he’s kindly, avuncular, and intent as he inscribes a copy of his just-released Collected Poems. On the table we see his Swiss Army knife and a bottle of black ink for his Mont Blanc pen.

21

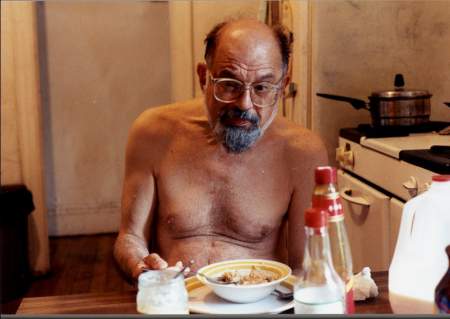

Today, twenty-one years after this shot, a decade after Allen’s death, I remain in awe of his generous adaptability as photographic subject: he was always tolerant – always open – towards my efforts at, so to speak, “capturing” him. I shot him eating, I shot him in the bathtub, I shot him sitting on the side of the bed performing his daily diabetes blood sugar level check. I shot him with a sizable boa constrictor crawling over his arms and hands, up his chest and onto his shoulder. I shot him, to move to the next in this group of photos, at midmorning breakfast the first day of summer 1991. He’s sixty-five, bare from waist up at his kitchen cereal, in all his frailty (“Tiresias with wrinkled breasts” he sighed, paraphrasing Eliot as he beheld the print.) To state the more than obvious: I wouldn’t have these photos without such an extraordinary, willing, and gifted subject.

Allen Ginsberg at midmorning breakfast, E. 12th Street apt., June 22, 1991. Photo Copyright © Gordon Ball, 2006.

22

In the decade before this breakfast shot, he’d renewed his sense of himself as a photographer, exhibiting his own archival photographs and taking new ones at such a rate that the celebrated Berenice Abbott warned him, “Don’t be a shutterbug, young man!” Publishing a major volume of his work – Allen Ginsberg:Photographs (Twelve Trees Press) in 1991, the poet-photographer wrote:

23

As artist companions, my contemporaries & friends in the early 1950s photos were involved in seeing each other as mythical or sacred in a sacred world; or not so much mythical as seeing each other as real in a really sacred world. My motive for taking these snapshots was to make celestial snapshots in a sacred world, recording certain moments in eternity with a sacramental presence. The sacramental quality comes from an awareness of the transitory nature of the world, and awareness that it’s the one and only occasion when we’ll be together. This is what makes it sacred, the awareness of mortality, which Keats’ Romantic poetry articulates as well as Buddhist dharma teaching.

24

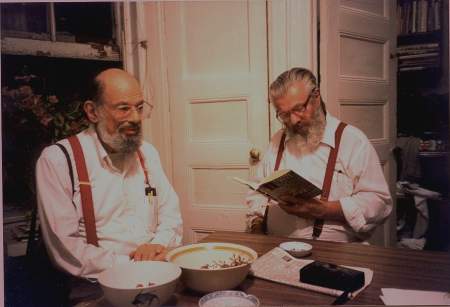

In the next to last shot I took of Allen and Peter together – June 1996 – I see that awareness of mortality written loud & clear across Allen’s face. A once blond and slender Orlovsky, now portly with dark steel grey hair and beard, sits at Allen’s small kitchen table. They wear white shirts with red suspenders, the bowl of grapes on the table is mostly eaten through. I can “see” – I can read into the photo – the signs of Allen’s congestive heart failure in those days, his difficult breathing ten months before his death. He appears contemplative, ruminative, and is looking elsewhere than at the camera, as Peter’s absorbed by punk rocker Richard Hell’s novel (its title obscure in the photo) Go Now.

Allen Ginsberg and Peter Orlovsky, 437 E. 12 St., June 1996, before we left for a flashlight tour of Allen's new loft on 13th St. and dinner at the Mee Noodle Shop & Grill on First Avenue. Peter is reading Richard Hell's «Go Now.» Photo Copyright © Gordon Ball, 2006.

25

After the sale of his papers to Stanford University in 1994 Allen was able to buy a loft on East Thirteenth Street to spend his last years or decades: on the fifth floor, with an elevator that was now a necessity, and with a bedroom for his stepmother, Edith, a widow since 1976. But he died half a year after moving in, rather suddenly, in the spring of 1997, of liver cancer. I was lecturing on him as he laying dying, and got to New York in time for the two funerals, one private and one public, on April 6 and 7. On the 8th his secretary Bob Rosenthal invited me to the loft to shoot some video as a documentary record; I also brought my pocket-sized Olympus.

26

Thus, the last shot chronologically focuses on Allen’s decades-old case containing his harmonium, the small musical instrument which he bought in Benares 1963 and used at countless readings and performances around the world. Here we see it on the hardwood floor of the new loft, partly lit by April mid-morning sun: surviving still, with dents and red and white “FRAGILE” stickers.

Harmonium case of Allen Ginsberg, April 8, 1997, in his 13th Street loft. Photo Copyright © Gordon Ball, 2006.

27

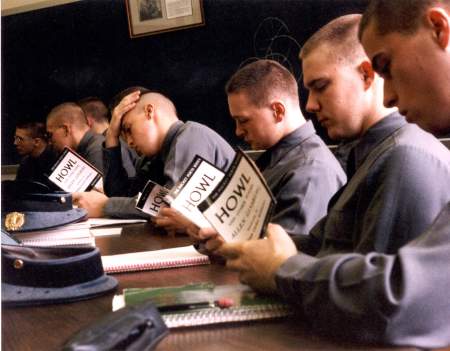

Though I’ve shared Allen’s recognition of the sacredness and ephemerality of life, and have striven to seize certain instants as they disappear, I’m not so articulate as to formulate richly and profoundly like Allen the whys and wherefores of my own picture-taking. And I can’t always say what’s in my head – or consciousness – as I shoot. Occasionally I feel that something is set, shaped, “programmed,” even, before me – as in 1991 when I recognized that an historical moment was shaping itself before my eyes, along interesting lines of perspective, when I shot “Cadets Read Howl”. But I also exclaimed to myself at the time, “It’s like everyone’s reading Chairman Mao’s Little Red Book!” And that photo, as one friend observed, is like a Rorschach test, for the range of responses it generates. One viewer even insisted – before digital manipulation was common – that it wasn’t a real photo, i.e. a documentation of something that happened.

Cadets read Howl, February 19, 1991, Virginia Military Institute, Lexington, Virginia. Photo Copyright © Gordon Ball, 2006.

28

Otherwise, often, I like to think that I don’t know what I’m doing when photographing. Thinking, or abstracting, can get in the way. As the great photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson has said, You don’t have to be intelligent to photograph. You just have to be intuitive.

29

In the end, I feel that the images which affect us most greatly are those that maintain an element of mystery, despite whatever efforts we undertake at analysis and explication. That certainly holds true for me in the case of two of the photos I most admire, both, of course by Cartier-Bresson: “Madrid 1933,” that extraordinary rendering of “the surrealism of everyday life,” and the most exquisite portrait I’ve ever seen: his shot from above of 75-year-old Matisse in his studio among his white doves.

30

I’m similarly moved by and indebted to many shots by Robert Frank, especially those in The Americans, starting with that extraordinary documentation of racial segregation in mid-50s New Orleans: the streetcar “photo strip” – the windows like the frames of individual shots – of unhappy people, black and white alike, with the only countenance even approaching a smile that of the black woman in maid’s uniform, bringing up the rear. And the material and spiritual bleakness of the book’s first shot, two framed human images dominated by unfurled flag and dark brick wall.

31

So those are two photographers (there are more) whose brilliance has given light to my own path; their inspiration has worked subtly, for as Eliot points out, any present work is in conversation with the richness of the past.

32

To return to my own photography: as I suggested earlier, I use both “conscious” and intuitive approaches. Of course, each is a simple tag for something more complex, more diffuse, and often more difficult to express. Once a gallery person looking at some of my prints asked that I characterize the whole of my work in photography (for I’ve taken many shots besides those of Allen and companions): my basic interest in the medium, what motivates me, what I’m “after.” “The distribution of light throughout the universe,” I wanted to say, but didn’t have the nerve to utter such a hifalutin’ mouthful. But it would’ve been the truth: light and all its variations and falls – not one thing, not another, not something else – but all of them.

33

At the same time, one can set limits, be specific, “frame” things. “Notice what you notice,” Allen advised poets, Buddhists, and photographers. I’d like to fancy that if you could see the entire range of my photographic effort, some of my earliest images through some of my most recent, you might note a progression in aesthetic awareness – some greater attention to detail, some greater eye for balance or symmetry or asymmetry. But it’s always interested me that two people can behold the same scene unfolding before them, or the same photograph in a book, and one will undergo a rich aesthetic experience while the other will have no such response. I’d like to say I’ve been both persons (maybe still am) – I didn’t appreciate Cartier-Bresson or Robert Frank at first, and still, today, cannot say what it is that makes one notice how a photograph “works,” other than immersion in the medium, and good friends pointing to things.

34

Seeing things take focus, shape, and form through Allen’s eyes, so to speak, as well as those of many others including Jonas Mekas, enriched my own sight – like the thrill of beholding an image form within a tray of developing fluid where but an instant earlier there was only blank paper. But perhaps the person who’s most enriched my vision is my wife Kathleen, who from our early days sat looking with me at reproductions of paintings, pointing out all that she appreciated; who drew my attention to line and complexity and form in all the natural world as well; who painted and sketched and quilted the seen patterns of her sensibility and intelligence. For me it’s been a gift almost unending, for in later years she’s also patiently spent countless hours evaluating new prints, suggesting how an image might be cropped here, brightened there – or throwing cold water in my face when I thought I had something truly wonderful that wasn’t at all – or stopped me from tossing out an image worthy of being cherished. Six years ago Kathleen was diagnosed with Macular Degeneration (the wet – the worse – of the two kinds), and though it remains in the early stages and though we try to do all we can with this progressive disease, there’s a sadness here I can’t express.

35

So awareness of our one and only occasion being together, and awareness of mortality, as Allen wrote, is inevitable, inescapable; without it we wouldn’t have art (“The sun’s not eternal, that’s why there’s the blues,” he once sang.). But my main thrust here is to celebrate my great indebtedness to other individuals, even as I try to practice an art often presumed solitary. In my view, a photograph doesn’t exist if it’s not seen. That’s a basic problem in any work – getting it seen, read, or heard. “Great poets need great audiences,” wrote Walt Whitman, and the same is true in the visual arts.

36

Previously I depicted myself in my very early days with camera in hand, not thinking of myself as photographer. By 1994 – when most of these images were already made – I still didn’t. But Allen had mentioned to me that in that year New York University would hold a conference on the legacy of the Beat Generation, and that he had recommended me as a speaker – and that there was going to be a small visual arts exhibit as well. I sent some samples to curator Bernard Mindich, and was exhibited for the first time.

37

That summer, I showed some of the same shots to Allen – you see for decades I’d sent little drug store prints to Allen and other subjects of my work, but hardly ever tried – or even thought – to publish any. Nearly two decades earlier he’d characterized some of my snaps as “little miracles of colored loveliness” – but I didn’t then, nor for many years, think of myself as a photographer. Now Allen offered, encouragingly, “You’ve taken some classics.”

38

That was, as I say, 1994. In the last decade I’ve become indebted to other individuals who’ve helped or encouraged in various ways. My friend Tom Whiteside, filmmaker and musician, showed a xerox of “Cadets Read Howl” to editors at DoubleTake magazine in 1996 which led to my first large scale photo reproduction in a periodical. Allen’s archivist Bill Morgan, a saintlike figure who carried out the impossible task of cataloging Allen’s 80,000 images , connected me with a gallery. And though he never claimed the title of agent, Bill represented me, interceded for me in a variety of efforts, and bought the first print I ever sold.

39

Dan Murphy, a superb printer at PhotoWorks in Charlottesville who as they say “understands” what I want to do with images, has made it possible for me to continue to bring out a few fine new prints a year. (I have to have my work done at a lab, which itself is expensive, for the cost of color developing and printing at home is prohibitive, and because I am confronted, in many cases, with negatives so old that, as Dan has put it, “The colors are walking away.”) My daughter Daisy has always been a great inspiration, and often the subject (patient and otherwise) of my shots. And there are others to whom I remain grateful — friends Alan Baragona, Rob McDonald, John Leland, Peter Maravelis, and Nancy Schoenberger — for repeated encouragement and support. The list goes on…

40

At this point, dear readers, I fear I’ve misled you. It may sound as if ever since my “outing” as a photgrapher things have proceeded just about ideally. But my taking of many shots which fall far short of my hopes and expectations; stolen prints; labs that seem to have no interest in my needs; a publisher who can’t remember my name after asking for (and receiving) my materials; prints damaged by UPS and US mail, prints (even with extremely high insurance) misdelivered by Fed Ex; and some museums and galleries not at all interested in exhibiting my work, in spite of my laying on my most endearing personal charm: such things make the help and encouragement of others the more meaningful, even poignant, for me.

41

So I’m grateful for the simplest positive words, just as for occasional wild bursts of enthusiasm. I’ve had the good fortune to exhibit in Lexington, Virginia, where I live, as well as in New England, New York, the Midwest, California, and, most recently, in China. I’m indebted to everyone who’s made such things possible, as I am to John Tranter of Jacket and all of you who’ve taken a moment to glance at these words and images.

Gordon Ball and his wife Kathleen; Photo by Eduardo Wall

Gordon Ball edited three books with poet Allen Ginsberg, including Pulitzer Prize nominee Allen Verbatim. His photographs of the poet and his colleagues, “Ginsberg & Beat Fellows” have been widely exhibited and published, from the Sunday New York Times magazine to the Rolling Stone Book of the Beats. Ball is as also an award-winning filmmaker and the author of a memoir centered in New York’s counterculture, ’66 Frames (Coffee House Press). His East

Hill Farm: Seasons with Allen Ginsberg is represented by agent Sterling Lord. A volume of his prose poems, Dark Music, has just been published by Cityful Press. More of Ball’s photos appear on his homepage http://www.gordonballgallery.com/. His films are available from Canyon Cinema at http://www.canyoncinema.com/; and Filmmakers’ Cooperative at http://www.film-makerscoop.com/. ’66 Frames and Dark Music are sold at City Lights Bookstore in San Francisco and are available through Amazon. Dark Music is also available from Cityful Press, 1039 Lilac Street, Longmont, CO 80501 USA. To purchase a photographic print contact Gordon Ball, 339 Sugar Creek Road, Lexington, VA 24450 USA.

[You can see a slideshow of the photographs in this article here. — Ed.]