Bio notes on the contributors, at the end of this very long file:

George Bowering

George Bowering

Maxine Chernoff

Maxine Chernoff

Katie Degentesh

Katie Degentesh

Gabriel Gudding

Gabriel Gudding

Rachel Loden

Rachel Loden

Ange Mlinko

Ange Mlinko

K. Silem Mohammad

K. Silem Mohammad

D. A. Powell

D. A. Powell

Ron Silliman

Ron Silliman

Gary Sullivan

Gary Sullivan

You can read 24 pages of poems produced by these contributors in this issue of Jacket.

This piece is about 80 (eighty) printed pages long.

It is copyright © the individual contributors and Jacket magazine 2007.

1

Preamble: The Humor in Poetry email discussion group (HumPo) launched on October 17, 2005, with ten participants: George Bowering, Maxine Chernoff, Katie Degentesh, Gabriel Gudding, Rachel Loden, Ange Mlinko, K. Silem (Kasey) Mohammad, D. A. (Doug) Powell, Ron Silliman, and Gary Sullivan. David Bromige was our silent dancing partner (receiving all the posts) and the involvement of other group members waxed and waned, depending on their level of interest and other responsibilities. The full record of the conversation goes on for close to 200 pages; what follows is an edited excerpt from the proceedings.

paragraph 2

HumPo was hatched five years ago in the middle of the night, the hellspawn of a listserv notice from Ron Silliman and my own pre-dawn colloquies and confusions. The spark from Ron came in a couple of lines from his December 23, 2002 post to the POETICS list and elsewhere, “The latest on the Blog”:

3

On The Postmodern Wink: Why Humor Doesn’t Travel Well In Poetry

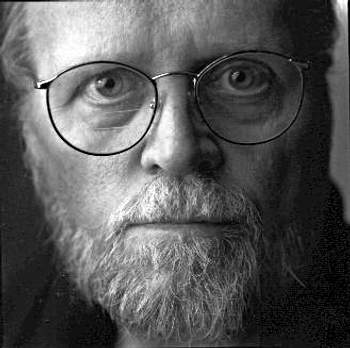

Ron Silliman, photo Jeff Hurwitz, 1998

4

When I clicked through to his expanded consideration of these issues (Silliman’s Blog, December 15, 2002), I found something substantially more nuanced than the teaser, and I agreed with a lot of it. I agreed for instance that “Context is so important in humor &, by definition, so pliable & subject to change, that it is almost impossible to ensure that what is uproarious in one setting will remain so over time.” The key word there, it seemed to me, was almost. Wasn’t it equally impossible to ensure that what seemed “serious” in one setting would remain so over time? I thought of Oscar Wilde’s quip that “One must have a heart of stone to read the death of Little Nell without laughing.”

5

Ron was right that most attempts at humor would not travel well, because most poetry was destined for the dunghill. None of us knew whether the good qualities with which we hoped our work was endowed would play well over time. But this was equally true of “serious” poetry. One had only to think of all the dreadful serious poetry being written today, its authors faintly trembling with the conviction of their own significance.

6

Poems that took on the world in its crude, unrefined state (I went on arguing to myself), could not fail to engender a certain amount of hilarity. How could one write about history, say, without a mordant — or at least a rueful — sense of humor? It could be done, of course, but only by stripping history of its rich contradictions, its complexity.

7

So it seemed to me that the whole notion of “seriousness” could benefit from some scrutiny, if it represented a worldview that excluded the splendid parade of paradoxes and absurdities that made up the comic underside of human life.

8

Was seriousness, in its myopic heart, fundamentally nonserious?

9

Ron’s teaser crystallized something for me: a sense in some quarters that funny poetry, or poetry that even flirted with the comic, was inevitably more perishable than its “serious” cousin and would, like Rodney Dangerfield, get no respect. This was as true in the “post-avant” world as it was in what Ron liked to call the School of Quietude.

10

Since much of the poetry that had mattered most in my own life (some of it coming down centuries and millennia) had been funny poetry that stayed funny, I wanted to take up Ron’s excellent challenge. To do that I had to kick around these issues with a group of people who could engage them in a complex way. Thus this conversation.

11

I asked Kasey to co-host with me and he graciously agreed, coming up with the name HumPo, a stroke of genius.

12

Rachel Loden: I have a question for Maxine. In an interview in Transfer 73 (Spring 1997) you’re asked about the “quirkiness and humor” of your prose poems, and how you think that translated into your longer works. Here’s some of your answer:

13

I was just talking about that in my MFA fiction class. A man in my class said that he’s no longer funny. I didn’t know him so I didn’t know whether that was true. I said, “Do you have children?” and he said “Yes.” I said, “That’s why you’re not funny anymore.” When I was younger, it was easier to be funny. It was easy for me to see the odd or unusual in a situation rather than its deeper ramifications. Surface is funny, not depth. But as I got older, I wanted more unity in my writing. I was less interested in an easy laugh than in looking at what makes things what they are.

14

Reading this now, I’m struck by how funny it is — your story about the man who isn’t funny anymore. But when I first read it, I had just written a review of your book World for Jacket. In it I had said things like “In Chernoff’s poems, wit cuts in and out of the melodic surge and flow, but rather than undermining her arguments, the effect paradoxically heightens their poignance.” And “Wherever it appears, the comic is a locus of compressed energy, providing as much delight as relief.” And “The absurdist-playlets-cum-vaudeville-skits that dominate the fourth section of World are some of the best fun ever vouchsafed to a poetry book. Each of these routines is a valiant attempt to limn the shape of human logic, a project that turns out to be both daunting and curiously satisfying.”

15

I immediately decided that reviews were not my bailiwick. How had I so completely misread your intentions? Was some of what I found so compelling in your work evidence of my own superficiality? Was the funny not deep? Were laughs really so easy to get, and did they not cut to the heart of “what makes things what they are”?

16

I thought they did — but clearly there was something I wasn’t getting. Could you possibly throw some light on this and help me with my bafflement?

17

Maxine Chernoff: I think I was expressing personal anxiety rather than a definitive analysis of humor. At least in my own case, it’s been true that although incidents, interpretations, snippets of conversation, the body politic, etc., remain funny, I no longer have an easy time laughing them off. The serious is deeply funny but that doesn’t inoculate one from the pain. So I guess the pain is funny too. Much humor scratches at the surface of cruelty, shock, folly, and even terror. I read somewhere that a woman in the South (this may be apocryphal) saw a life-size Jesus balloon untether itself and ascend toward the sky from a car and in response leapt out of her car to follow him into heaven and died. Funny? Awful? Both? I watch Donald Rumsfeld telling his persistent lies in his wooden, cocky, jackass manner. Funny? Awful? Both? People are dying because of him — do I have a right to laugh?

Maxine Chernoff with Cheddar, photo Paul Hoover

18

Gabriel Gudding: I liked what Maxine said about her previous formulation, and about Rumsfeld and the Jesus balloon tragedy. Reminds me of what Giordano Bruno wrote: “In hilaritas tristis, in tristitia hilaris.” The horror/sorrow nexus is deeply a part of the laughter/detachment nexus. I see the same thing in Viktor Frankl’s great account of how he survived in Auschwitz and his crediting humor’s ability to remake the world, create a future, and awaken a healthy detachment from horror in his 1963 bestseller Man’s Search For Meaning.

19

The formulation that comic writing is something that is more ephemeral than (what?) tragic or serious writing is, and I’m just going to say it, stupid bullshit. How is Ron’s attack on it not Aestheticist? There is nothing about the inherent structures of comedy that make them any less beholden to cultural and existential context than any other emotional mode or subgenre. Some of what has passed for profoundly serious work strikes me today as profoundly funny and self-parodic. I can’t read a whole lot of Ezra Pound, for instance, without shaking my head at the unintended goofiness of it. The emotional context of a poignant work can just as easily be cut adrift of audience expectations as a comic work. I think we just tend to notice it more when comedy does this. One of the reasons we notice comedy’s failure more is that it has much more both subversive and soteriological potential than High Serious Mode: it risks more, challenges more, and, when it rocks, it achieves more.

20

Bakhtin in fact went so far as to say that laughter “liberates from the fear that developed in man during thousands of years: fear of the sacred, of prohibitions, of the past, of power.... Laughter opened men’s eyes on that which is new, on the future.” And Bakhtin goes on to say that Medieval laughter, in challenging the church, in fact prefigured not only the Reformation but the Enlightenment. Laughter’s efficacy is on the side of revolution, health, and the casting out of the old order and irrational law. So it’s not about a “wink”: it’s about a whole fuck you. Fuck you because I love you. Fuck you because we’re better than that.

21

Rachel Loden: Yes, have to say I’m not much enamored with the whole notion of “the wink.” It’s so trivializing. It signals that comic poetry is minor poetry and that comic poets are precious, passionless aesthetes.

22

Not that I have any quarrel with beauty, you understand. It’s just that for me, comedy has so much more to do with fury than with distancing oneself from the world.

23

George Bowering: Wonderful turn of phrase! I am glad I got in on this. Of course, Rachel has an advantage over us, taking Richard Nixon as a subject. Has a step up on the grotesquely funny. Whoever said that the funny is at the edge of the horrible catastrophe is right, and we have grown mature while Dan Quayle and George Doubledome Bush have led the discussion.

24

K. Silem Mohammad: Ron Silliman has just been added to the group. Welcome!

25

Gabriel Gudding: Well, that’s just great. Just great. After I called Ron’s argument (the one mentioned by Rachel) “stupid bullshit,” you go and invite the guy! :) Ron, you probably better look at what I said.

26

Ron Silliman: That’s me, the aestheticist alright. Actually, I do like humor in poetry — in all writing, actually — it’s “funny poems” that irk, & there’s a distinction.

27

One thing I might want to note is my brief career — a couple of shows in June of 1964 in Newport, RI — as a professional stand-up comic. I was 17 at the time & it was a terrifying process. Even using material cribbed from Lenny Bruce & Alan Sherman (I was eclectic in what I stole at least: I would have borrowed from Lord Buckley if I could have figured out how to do so), I was utterly dreadful.

28

Rachel Loden: Maybe, but I would have given anything for a ringside seat. With a videotape I could control the world!

29

But whatever possessed you to do it?

30

Ron Silliman: I had hitched all the way to the Newport Folk Festival in Berkeley without the necessary rudiments: (a) a place to stay or (b) a sleeping bag. I stayed at the Y for a couple of days before the festival began, but once it started the Y was booked. The only other hotel in town, the Viking, was completely booked with performers. But there was a coffee house that offered free accommodations (as in “sleep on the stage if you can”) to volunteer performers. I knew I wasn’t a singer and I didn’t (yet) own a guitar. So it was a matter of necessity. After the first night, they let me stay for the week without further humiliations. It turned out to be a very nice little scene there where I connected up with people who took me back to the East Village, so I had accommodations there for some time as well (and then later also up in Woodstock, as it happened). My summer of bumming around.

Ron Silliman as a baby (painting by Michelle Buchanan), photo Michelle Buchanan

31

Maxine Chernoff: So the Fibonacci Number Series walks into a bar....

***

32

Rachel Loden: Here are some questions for the group:

33

1. Why does funniness get no respect? “Dying is easy. Comedy is hard,” as they say in showbiz.

34

2. Why are you funny? On Fresh Air one of the members of Monty Python [Eric Idle as it turns out] said that he was funny because he was damaged, and that that’s why other people were funny as well.

35

Does funniness spring from some kind of wound?

36

If you disagree with this point of view, how do you explain the prevalence of Jews and other outsiders in comedy?

37

Ron Silliman: There is an assumption in the Python’s response that possibly there are people who are not damaged. I have never met those people.

38

Maxine Chernoff: On the issue of otherness and funniness: One of the funniest and most frequent circumstances to observe is ineptitude. Outsiders in general can offer a more cogent critique of ineptitude since they observe the workings of systems — organizations, cultures, governments, theories, etc. — from their outsider status.

39

On funniness and respect — there is a term, “light verse,” which is a pejorative. There is no contrary term such as “heavy(-handed?)” verse. If there were to be such a term, it would suggest to me the calculation of producing an effect in a reader by seriously portraying an often trivial situation without humor, in order to provoke pathos: A bird crashes into my window. Why is there pain in the world? In other words, the lyric tradition as portrayed by many of our most “respected” mainstream writers such as, say, Stanley Kunitz, who has a poem about finding a dead bird on his lawn.

40

D.A. Powell: Maxine, you’ve reminded me of a similar heavy-handed (I like this term!) poem, William Stafford’s “Travelling Through the Dark.” Bromige had a wonderful response to Stafford’s “thinking hard for all of us”:

41

“Thanks, Bill. We wouldn’t have known what to think otherwise.”

42

And of course the heavy-handed poem is ripe for parody. Rae Armantrout’s take on the Stafford poem is still one of my favorites. Of course, all of the above examples revolve around dead animals. I’m sure this is only a sub-genre of the heavy-handed.

43

Ange Mlinko: I agree so strongly with Gabe’s post (well, with each post thus far) that I wondered if there was anything left to say. After all, one can’t argue against comedy. Like colorblindness or a tin ear, one can be immune to it. Does literature self-select for the morose? The dogmatic?

Ange Mlinko, photo Samir S. Patel

44

I managed to get to the Poetry Project on Wednesday to see an old friend from Boston, Ed Barrett, read with one of my old teachers, August Kleinzahler. If you don’t know Ed Barrett’s work, you should try to find Sheepshead Bay (Zoland Books) or Rub Out (Pressed Wafer). At the Project, he read “Goethe Did Not Invent Physics to Murder Anyone.” That title in itself sort of encapsulates his brand of humor: a longtime teacher of game design and writing at MIT, he adapts the light, witty New York School poem to include references to science and philosophy, and his Brooklyn Irish-Catholic childhood. And in his hands the “light, witty” turns into something else — a transparent attempt to hold love and pain at arms’ length. And while that in itself may sound like a cliché, the “transparent” part is all too often missing from other poets. He is a great acknowledger of his own moves.

45

“Vicki said she had a child from a previous relationship, and the ocean is the Saltines of time, to find not just yourself, the single grammatical soul fluttering like a syringe above the miniature Japanese forests of scrub oak on Nantucket, certainly not clarity or truth in the cross hairs of heaven.” (“Lyrical Ballads”)

46

That’s a pretty great sentence.

47

Well, the audience response to Barrett, and of course to Kleinzahler, who, lucky him, has the timing of an actor (being funny on the page and being funny at the reading podium, whoa, that’s another topic) was overwhelming. I don’t have any of AK’s books in front of me right now, but his specialty surely lies in making the reader laugh and squirm at the same time. He writes very creepy poems in the guise of the clown.

48

And I think that creepiness is what saves him from being “merely” funny, at least in the eyes of critics. Someone like Connie Deanovich, whom I think publishers should be falling over themselves to publish, doesn’t seem to write with any mixed motives (philosophical, psychological) and doesn’t get as much props. Or that’s how I see it.

49

Rachel Loden: Hear hear. Connie is completely underrated, and at 3 a.m. I’m often talking to myself about the reasons why.

50

K. Silem Mohammad: Ange’s point seems right on to me: no one wants to be in the thankless position of arguing against humor, no matter how much of a sense of it one may lack. So maybe the question isn’t whether humor is a “valid” aspect of poetry; it clearly is (although I am still interested in hearing Ron further define the negative example of the “funny poem”). Maybe a clearer question would be: what can humor do in poetry that other modes can’t? And accordingly, and perhaps more to our point, what particular risks are incurred in poetic humor? What cheapenings, escapist gestures, deflations of crucial tension, etc.?

51

Gabriel Gudding: I’d like to bring up three principal things humor does or can do.

Gabriel Gudding, photo Gina Franco

52

(1) It can democratize. Freud speaks of this in “Jokes and their Relation to the Unconscious.” He says that no one is immune to the leveling aspects of comedy: hierarchy is no defense against it. This is very different from its binary bugaboo, the tragic mode, or high serious mode, which is about hierarchy wherein typically the protagonist (or poetic speaker) is wrapped in prestige or status, or a kind of lyrical coolness, or on an emotional plinth, set apart from the audience. I think twentieth century American poetry was particularly susceptible to this kind of emotional racket. Comedy does not trade individuating emotions (centripetal or self-centered emotions) for prestige. Societies in the comic mode are not formed around such emotions.

53

Northrop Frye says in this really cool essay, “The Mythos of Spring,” that comedies (and he’s mostly talking about plays) tend toward an appearance of a new society — one which tends to include as many people as possible, and not infrequently it can include, especially toward the end, unsavory characters. It is about, in great part, an inclusive forgiveness. And in fact, in order to laugh, we have to be willing to let go of resentments. There is one kind of laughter, then, that is at base profoundly ethical: it forgives (I am not talking about the problem of derisive laughter at this point, more on that later maybe).

54

(2) A chief quality of this new society is that it arrives by casting off an older order; it frees people from a society governed by an irrational law or irritable personnel. We see this with the New York School or lots of other avant-garde movements: comedy is a principal tool of the avant-garde. Throwing off an old order can often only be done through laughter.

55

(3) A chief attitude of humor is that it’s about enduring, not suffering. Think of Wile E. Coyote, or any slapstick mode (whether it’s Buster Keaton or Kasey’s giant squid, whose poem is, by the way, on my blog): the dude gets back up. I think of Bukowski’s poem, “Trouble with Spain”: the speaker is in the shower and burns his balls, then he gets in a fight at a party, then the poem ends with him back in the shower, burning his balls and then turning around and burning his “bunghole.” Though there is pain and misfortune (and often extreme brutality in comic poems), there is no profound suffering represented. Humor is about not cashing in on our woes, but about taking a distance on them so that a triumphal attitude can be shared. E.B. White said that Humor is about a fuckyou (not his word) to death. That is why I think of the Crucifixion as a profoundly, at heart, Comic event. And in fact, Osiris, Dionysus, Christ — all those dudes got up again, just like Buster Keaton, just like Wile E. Coyote, just like the Giant Squid. E.B. White said that comedy encourages us to live as if we were already dead: as if, that is to say, we had nothing left to lose and the whole world to gain by not taking our suffering so personally.

56

And that idea that suffering privatizes, whereas comedy works against privatizing emotion — is very important (to me). Nietzsche said, “Mankind has suffered so excruciatingly in the world that he was compelled to invent comedy.” Comedy is an answer to suffering, encouraging us to endure in the face of it.

57

I have to fart.

58

George Bowering: Poetry and humor.

59

I wonder whether we can mention some that we might know in common, and see whether we have differing tapes. I am thinking, or have been thinking, of the book that was my bible when I was a young poet, the Allen anthology (or what was its name/ The New American Poetry 1945-1960?). Who is funny in there? The first poet I think of is Gregory Corso. Poems such as “Hair” and “Marriage” and “Bomb” struck one as impertinent, and funny. Still funny, I think; and no less performative of the time than The Maximus Poems, or Creeley’s “I Know a Man,” which is pretty funny, isn’t it? Why did Creeley, whose voice is so measured and sincere, pick funny to come at us, with say, the three old ladies in a tree?

60

[Quoting Maxine]: “Surface is funny, not depth.” This is the nub of something I have been thinking about for these decades. In the seventies I noticed two things about hip engaged contemporary fiction (I will think later about poetry), call it “postmodern,” “anti-realist” etc. etc.

61

(1) All of it was comedic, humorous, from Samuel Beckett humour to Kurt Vonnegut-busting. The Modernists knew one kind of humor — irony, and you weren’t supposed to laugh.

62

(2) Most of the interesting stuff was happening on the surface. Realism, especially psychological realism, with all its talk about “characters,” paid heed to that protestant given (and taken) that with depth comes complexity and even truth, honest to god. So we knew that some things were “facile” or “superficial,” whereas stuff that goes in deep and spends a long time doing it (such as Freudian analysis or D.H. Lawrence), was way to heck more worthwhile.

A still from George Bowering’s video, Lost in the Library, photo Elvis Prusic, 2006

63

Rachel Loden: George, can you say more about the interesting stuff that was happening on the surface? I think I know what you mean, but can you be specific? And is that interesting stuff still happening?

64

Also, do you include Beckett in the stuff at which we weren’t supposed to laugh? Because Beckett is laugh-out-loud funny, I think — do you disagree?

65

My copy of the Allen anthology is something of a religious relic at this point, held together by a rubber band — a collection of single pages and hunks of ripped spine. “Marriage” is still funny and energetic (although at moments a little dated) and I love the line “all alone in furnished room with pee stains on my underwear.” Which seems almost like something John Wieners might say, but in his poem it wouldn’t be as funny.

66

But the guy I think of in that anthology is Koch. “Fresh Air” is still one of my favorite poems of all time:

67

“Oh to be seventeen years old

Once again,” sang the red-haired man, “and not know that poetry

Is ruled with the sceptre of the dumb, the deaf, and the creepy!”

68

So I guess some things don’t change.

69

George Bowering: Well, see, when I was a kid the realists were all the thing. And psychological realism was the great accomplishment. Stuff that was

70

deep

hidden

under the surface

down in the unconscious

71

was the real truth, was important, was the goal of the investigative fiction writer or psychologist or teacher or lover et al.

72

Thinking otherwise, I got called superficial i.e. a guy on the surface. Dig, they said. All the stuff on the surface is a puzzle you have to figure out, dig deep. The deeper you dig the more significance you’ll find. Remember that? So when it came to writing a novel you were supposed to make your writing surface as smooth as possible, because that was no place to bring attention to. The genius of this was Graham Greene. He had a great transparent style, and there was always something hidden. That was the nature of love. That was the means of growing intelligent.

73

Remember when e.e. cummings was thought to be amusing but really not very “deep”? Remember how the professors said that Vonnegut is really just a teenagers’ novelist? Because his narrating voice was not neutral, and then he started drawing on the page!

74

No, Sam Beckett is the hero of the twentieth century as far as I am concerned. He took the implications of Modernism and pulled them to their limit and gave us what we needed for a post-Modernist read. The Unnameable is the end of the novel’s work, that’s what I thought; it gets rid of character (now, there is something you have to dig deep to understand, eh?), setting, theme, conflict, all that stuff. From now on Beckett would be a voice in your head, and it is your voice, that is all it can be while you are reading, and it is all to be found right there on the page.

75

Rachel Loden: Thanks, George — reminds me of the time when the highest praise for something was that it was “shattering.”

76

Seems kind of quaint now.

77

Gabriel Gudding: Regarding your question, Rachel, about the prevalence of Jews and outsiders in comedy, here’s Isaac Bashevis Singer: “It is a fact that suppressed people show more humor than the people who rule or are at home.”

78

And like Ron I’ve never met those undamaged people. If damage, flaw, hamartia, is a given, I think humor is a means of dealing with damage by appreciating suffering as just another form of change.

79

Humor seems to be a method of equanimity. It seems to be a means of practicing and exercising that kind of equanimity some people call detachment.

80

Seems to me the clown and the saint are really close in having this detachment from their own wounds. (Doesn’t the Yiddish word “zelig,” as in the Woody Allen movie, mean at once holy and silly?) The ability to “be at home” (in re Singer’s quote above) is what we see in Zelig, and it speaks, to my sensibility, to a kind of ability to “be at home” in an existential sense too: if we are all damaged, including the tragic protagonist bound in his “hamartia,” the problem of humor amounts to what we do in the face of that imperfection and damage. If we can be silly in the face of it, we can be holy. Seems to me that blatantly flawed people, whom William James called “sick souls,” have been forced by circumstances to get some distance on life, to appreciate constant change as both a benison and a fact.

81

I mean, a clown is someone who purposefully and theatrically makes a show of debasing herself by showcasing that innate damage: a clown takes on and “owns” her own flaws and wounds — and flaunts them so triumphantly that we, the audience feel on the one hand, superior to the clown and on the other we vicariously appreciate the courage of that clown for being so triumphant and skillful in the face of said flaws (big nose, funny moustache, whathaveyou — yet funny, awkwardly brave, and finally buoyant). In the case of a verbal clown [humorous poet], that “flaw,” that damage, comes in the form of buoyant nonsense, anarchic satire, tawdry rhyming, or incessant non-sequitur:

82

In other words, maybe humor is a triumphant display of detachment toward the inevitability of damage.

83

It’s a simultaneous owning and detaching from one’s flaws (and the fact that they are inevitably and incessantly incurred) that I think makes an inspired clown useful.

84

Rachel Loden: Yes indeed. And it’s certainly true that there are no undamaged people. The Python in question probably didn’t use the word “damaged” at all. That was my shorthand. I remember him talking about John Cleese (he was not John Cleese) and saying that Cleese had this fantastic anger from his childhood and that for decades he was working it out in comedy. I think we can see that rage in Cleese and it is a lot of what makes him funny. As Gabe says, he debases himself by showcasing that damage, he flaunts it and makes us admire his fearlessness in doing so. I’d add that when he makes us laugh we also fall in love with him. And all of that tumbles into the strange calculation of art.

85

So I know it’s unfashionable to say that people are unequally damaged or that their damage drives them crazy in different ways. But I think it’s also obviously true. The forces that create a Pryor or a Berrigan or a Cleese seem pretty intractable and I’m grateful that they did battle with them and didn’t become pimps or policemen or bankers.

86

Don’t know whether any of you watch The Colbert Report, which debuted on the same day as this list. I was lucky enough to hear Stephen Colbert speak the other day in San Francisco about his work in comedy and the deaths of his father and brother in a plane crash when he was a child. It was clear that this had everything to do with what he became. So he seems very much the picture of what Gabe calls “a triumphant display of detachment toward the inevitability of damage.”

87

George Bowering: [quoting Rachel]: “How do you explain the prevalence of Jews and other outsiders in comedy?” I do not know about that. But in my correspondence with the great Canadian poet and American Biblical scholar and translator, David Rosenberg, I asked him how come God told Moses etc. that there were to be no graven or molded images, and then when it comes to ordering an ark of the covenant, he says there has to be a couple of cherubim with wings. David said that he had told me years ago: God is ironic.

88

Thinking about the suggestion that comedy seems somehow normal to the oppressed or marginalized. But who are the funny African-American poets, outside of Ted Joans and maybe Bob Kaufman? And I was looking through Canadian poetry for humour, and hardly any women poets there/here work with funny, maybe a few.

89

I do recall, down there, Levertov saying “the authentic,” rising from the toilet seat and really wondering whether she might not be being funny.

90

Gabriel Gudding: George — here are some funny African-American poets (tons more but don’t have books in front of me at home here): Crystal Williams, Harryette Mullen, Amiri Baraka, Tony Medina (the almost self-parodic tawdry anger in first part of his “Capitalism is a Brutal Motherfucker” is very funny), Terrence Hayes, Lucille Clifton is very funny sometimes, Jayne Cortez, Sonia Sanchez — this list is really long, especially in re hip-hop generation poets.

91

As regards funny women poets: in addition to present company of course, are folks like

Lara Glenum, Jennifer Knox, Shanna Compton, Barbara Barg, Connie Deanovich, Denise Duhamel, Bernadette Mayer, Alice Notley, Amy Gerstler, Sheila Murphy, Brenda Coultas, Mary Ruefle, Julie Otten, Anne Waldman, Laura Mullen, Mairéad Byrne and lots of others.

92

Ron Silliman: I think that Lyn Hejinian & Rae Armantrout can both be quite funny. Ditto Laura Moriarty, Rachel Blau DuPlessis. But there are some, like Susan Howe (who reminds me a lot of Levertov in this regard) who seem very suspicious of this.

93

George Bowering: I don’t know. I have been reading Amiri Baraka since long before he was Amiri Baraka, and I have heard him read in San Jose, Buffalo, Boston, Victoria and Maine, and have been excited to be sharing the world with him, even being in the Air Force at the same time, but I haven’t noticed his being funny a lot, though once in Buffalo I heard him being pissed off at a Volkswagen that was supposed to pick him up, calling it a “Nazi car.”

94

D. A. Powell: I think Lucille Clifton is a funny African-American poet. Also Ray Durem, Etheridge Knight (his “I Sing of Shine” always makes my students laugh), Tim Seibles, Crystal Williams, John Raven, Thomas Sayers Ellis.

95

Gary Sullivan: A whole realm of humor, satire, and/or wit strikes me as coming out of unease. Maybe more on horror and humor in a bit, but a quick note: horror always strikes me as on some level very funny, but often in a particular way. We laugh at a lot of it I suspect because we’re freaked out about our bodies, and horror exposes, brings to the surface, manipulates, and seems to simultaneously understand and even sympathize with, even as it mocks or exposes, this fear.

Gary Sullivan, photo Nada Gordon

96

When I’ve seen horror films in theaters, people are usually laughing during the most disturbing parts — often much harder than they laugh during comedies. It always strikes me that that laughter — and I’m laughing along with everyone else — comes out of a general unease that these films tap and exploit. It’s often a kind of nervous laughter. Similar maybe to the kind that some of Lenny Bruce’s material makes manifest. (More on that in a bit.)

97

Another major unease that seems to often give rise to laughter is a general one with departures from perceived or desired social norms. Sexist, racist, homophobic, etc. jokes being one obvious manifestation. As are jokes making fun of sexist, racist, homophobic etc. behavior. Both seem to come out of an unease with those not conforming to one’s perception of social norms and/or niceties, and both seem to be a kind of attempt at shaming.

98

It’s been more than a decade since I’ve read any of the “age of reason” or “age of wit” writers, but my memory is that the motivation behind a lot of this writing was an attempt to “reason through” the natural world, including social systems, with the ultimate goal of controlling the social for the ultimate betterment of mankind.

99

My memory of reading Pope, Swift, and especially Addison & Steele, was of an underlying program, generally, to address, shame, and ultimately change aberrant behavior into something conforming to some “healthy” (e.g., Christian-but-informed-by-science-and-philosophy) ideal.

100

It always struck me that Pound thought a lot of his poetry was funny, or at least satirical, to the extent that he meant to expose & even at times shame those whose ideologies (political, social, aesthetic, etc.) he didn’t agree with. Some examples from Blast:

101

Women Before a Shop

The gewgaws of false amber and false turquoise attract them,

Like to like nature. These agglutinous yellows.

102

Or:

103

The New Cake of Soap

Lo, how it gleams and glistens in the sun

Like the cheek of a Chesterton.

104

Or:

105

L’Art

Green arsenic smeared on an egg-white cloth,

Crushed strawberries! Come let us feast our eyes.

106

And from the Vorticist Manifesto:

107

8. We set Humour at Humour’s throat. Stir up Civil War among peaceful apes.

9. We only want Humour if it has fought like Tragedy.

10. We only want Tragedy if it can clench its side-muscles like hands on its belly, and bring to the surface a laugh like a bomb.

108

... these examples, most obvious in the latter, being part of a general program to “Set up violent structure of adolescent clearness between two extremes.”

109

I hate this period of Pound. I don’t find myself returning to Addison & Steele or Pope much, either, although I still read Swift.

110

Not that they’re all doing the same thing. But this all seems to be coming out of I guess a moral appeal of some kind.

111

I often wonder, with humor/satire — some of my own included — how much of it comes from some level of unease with difference and (often unexamined) need or desire for social conformity — in addition to all of the other impulses, desires, thoughts, beliefs, and so on it all may come out of.

112

I also wonder, given the “outsiders & comedy” thread, how much comedy by socially-perceived “outsiders” plays with this unease over difference, exploits and exposes it. I think immediately of Lenny Bruce’s “How to Relax Your Colored Friends at Parties.” I actually think that that piece is so continually funny and brilliant not because it attacks subtle racism, but because it simply exposes it — which I suspect is not the same thing, quite. It makes the audience more of a participant, if that makes sense. You feel, in yourself, what he’s on about, as opposed to “seeing it” (in others). Ultimately, it’s a far less comfortable position to be in. Which may be why we keep laughing at or with it.

113

D. A. Powell: I used to think only that comedy was tragedy saved from itself — i.e. Harry Greener’s fake heart attacks in Day of the Locust are funny; his real heart attack is not. But the “is” and the “is not” of that example only apply to the context of the lives and perceptions of the other characters. For the reader, the fake heart attacks are the ones that read as pathetic and even tragic; the real one, by comparison, is almost comic relief, especially with the addition of the funeral. In fact, most of the comic moments of West’s novel are comic to the reader but not in any way funny. West (born Weinstein) practiced humor that celebrated the schtoch (“pricking”) and schlock (the “badly made”) elements of characters. The key to “getting” the joke was to know what was being deflated by the schtoch and/or to know what was being made apparent by the schlock.

D.A. Powell in front of Brainard’s Nancy Diptych, Berkeley Art Museum, photo Kevin Killian

114

Berryman’s Dream Songs employ a similar mode of humor. By staging Henry Pussycat’s life in blackface, Berryman is able to draw a comparison between Henry’s suffering and the suffering of African-Americans while at the same time showing that such a comparison is schlock because he has relied upon a faulty, irreverent, unsuitable vehicle at the outset. The schtoch occurs by saying the unsayable, and that’s given a further pathos in that it often occurs in sloshy “drunkspeech” or in minstrel show “dialect.” The humor arises as the reader perceives the deflations and (intentionally) badly made phrases, and also as the reader comprehends how close to tragic the speaker’s words are.

115

Jaws was not a movie that was funny when it premiered. But it’s funny now, because we’re able to look beyond the convincing to the unconvincing — the moments when the shark is so obviously mechanical, the moments when the camera is so willfully moving toward Scheider’s face to register panic. In essence, we’ve learned, through repeated viewings, to see for ourselves the schlock. The only key difference I suppose is that Spielberg didn’t intend for us to view the movie that way; and for me at least, that only adds to the pleasure. An even funnier Spielberg movie — and not for lack of trying — is The Color Purple. How in hell did he manage to get Oprah Winfrey to say “What you tell Harpo to beat me for?” without peeing her panties?

116

I guess, though, this line of inquiry is more about the unintentionally funny.

117

What are some of the great unintentionally funny funny poems? The contemporary McGonagalls?

118

Rachel Loden: Such a great question. This one makes me laugh, especially the ending. Maybe it’s the picture of her banging her parents together like paper dolls. And then the portentous solemnity with which she takes up her burden at the end — when I sense she is actually shivering with self-congratulatory joy.

119

I Go Back to May 1937

I see them standing at the formal gates of their colleges,

I see my father strolling out

under the ochre sandstone arch, the

red tiles glinting like bent

plates of blood behind his head, I

see my mother with a few light books at her hip

standing at the pillar made of tiny bricks with the

wrought-iron gate still open behind her, its

sword-tips black in the May air,

they are about to graduate, they are about to get married,

they are kids, they are dumb, all they know is they are

innocent, they would never hurt anybody.

I want to go up to them and say Stop,

don’t do it — she’s the wrong woman,

he’s the wrong man, you are going to do things

you cannot imagine you would ever do,

you are going to do bad things to children,

you are going to suffer in ways you never heard of,

you are going to want to die. I want to go

up to them there in the late May sunlight and say it,

her hungry pretty blank face turning to me,

her pitiful beautiful untouched body,

his arrogant handsome blind face turning to me,

his pitiful beautiful untouched body,

but I don’t do it. I want to live. I

take them up like the male and female

paper dolls and bang them together

at the hips like chips of flint as if to

strike sparks from them, I say

Do what you are going to do, and I will tell about it.

— Sharon Olds

120

D. A. Powell: It’s the “I want to live” that floors me there.

121

Kevin Prufer turned me on to a perfectly wretched book by someone named Neil Azevedo. His poems are funny not only because of his tin-eared formalism, but also because they’re so full of pomp without any real engagement of their subjects. This one makes me howl:

122

Marco Polo

a game of hide-and-seek

Stunned by the blindfold he is lost

in this front yard suddenly fragrant,

fraught with dark, the bark-hiding moth

deep in alfalfa roiled with gnats,

the hesitations that coil in bats,

his body hedges and prepares for harm

behind the focus of his less familiar eyes,

behind the faithless, fearful and soft cloth,

feckless, haptic, dazzled and still;

he works his way through grass filled

blindly by others’ passing and their pause

and the giggles as he falls

to stupor, to gesture, to the awful rules.

He flees a sweat-bee flanking his ear,

and sightlessly searches for all of his choices

until it’s clear; he fumbles the way of their voices.

123

I keep thinking that the moth’s bark is somehow worse than its bite? And I can’t imagine what makes the front yard “suddenly fragrant” unless it’s dog poo. What are “less familiar eyes” if they’re his? And how high is the grass if it has to be worked through?

124

Of course, I also think Bishop is a scream, though she probably wouldn’t have seen her work the way I do. I mean “somebody loves us all” for Christ’s sake? Doesn’t that make you pee your britches?

125

Gabriel Gudding: These poems are hilarious, if read in a certain way.

126

I some time ago guest edited a few magazines. In doing that, I published two poems by someone whose work I thought at first was meant to be funny but later realized was probably serious. Either way, I found/find it interesting.

127

I still find the pieces I published very funny, even hilarious. In fact, I find the humor in one of the two poems to be so “on” as to be ingenious. I only later, after meeting the author and seeing her other work, realized that she in fact did not intend them as comical at all.

128

I took the pieces because I thought she was writing parodically. I think her writing would make a fascinating study of poems with seriously ambiguous emotional valences.

129

It’s mostly because I did not know the general emotional trend of her work that I was unable to assess its emotional content and thereby determine whether or not it was ironic, and, if ironic, whether it was parodic or satiric or what. I made an assumption, that is, about her character, her Ethos, as Aristotle would have it, and her reading of the kairotic considerations of the issue I was guest editing. A fascinating study of hermeneutics replacing authorial intent to such a degree that the work’s genre is called into question.

130

D. A. Powell: Yes, I do detect the same tonal qualities [in the poems Gabe published, not quoted here] that I love in Koch — a kind of histrionic performance meant to show how uninteresting emotion qua emotion really is. But I can’t tell either if she’s meaning to be funny or if she is being funny in spite of herself.

131

Do you know Caroline Knox’s work? Caroline is obviously working through the same modes as Koch and revelling in them. But when she performs her work, she always wears the drag of shock, as if it would never have occurred to her to think of poetry as anything but serious. Of course, this only adds to the enjoyment. I don’t think I’d derive the same pleasure if she were of the “wink, wink/nudge, nudge” school of readers.

132

Rachel Loden: I’m guessing “funny in spite of herself,” especially where olfactory perceptions come into play. Interesting that “this front yard suddenly fragrant” is one of the funniest lines in the Azevedo. Is there something inherently funny about the sense of smell? I bet Gabe has done a study of this.

133

Maxine Chernoff: I guess when we laugh at the unintentionally funny we’re laughing at ineptitude, which in poetry is often tonal or imagistic. Once at a band concert of our daughter’s, a fellow 5th-grader could only elicit monstrous, elephantine noises from her trumpet. She tried and tried again. The adults were trying so hard not to laugh that we almost died. Imagine professional ballerinas who can’t dance (see Vonnegut’s story “Harrison Bergeron”) or slow-witted comics (I guess there are plenty of those) — and an audience suffering through. Isn’t that what’s happening in a seriously bad (aka unintentionally funny) poem? Only we are “viewing” it privately and can decide to stop at any point. It lacks the social pressure of a public viewing of a seriously bad performance, which is maybe why we can respond “better” to it. We’re alone with the engagement and can disengage whenever we wish. Do people feel as inclined toward pleasure at seriously poor poetry readings?

134

Gabriel Gudding: Doug, yes I know Caroline Knox’s work and have enjoyed it, but have never seen her perform. I once read (tho haven’t seen it in any of her books) an “Epic Spam Haiku”: she took the contents of a can of Spam and broke it into 17 syllable haiku — went on for pages.

135

Rachel, no never done a study of smells and humor but I read an essay recently by Ivan Illich about smell, spiritual knowledge and social intimacy: Illich says smell holds a special place as a sense because it’s such a socially intimate one (as opposed to touch’s sexual intimacy). For me, smell is socially horrifying because we often don’t know who’s emitting it — so any questions about it are always dangerous and freighted. Its source isn’t locatable, like a sound say, so there’s a whole lot more tension about smell. Plus “suddenly” doesn’t really go well with smell: it’s a slow-moving thing, a scent, right?, so it implies that Azevedo’s speaker is himself clueless or slow.

136

And Maxine, the thing that I personally find so funny in the poems I published and the Azevedo (and the Olds too but less so) isn’t so much incompetence (tho I see your point) but an emotional expenditure that seems too large, as if it were slow or plodding. The poet is hanging a great deal of gravitas on something that really isn’t worth it, as if they were weeping over something that doesn’t warrant weeping. So, it is a kind of incompetence, I can agree with you there, but it’s, for me, more specifically a matter of emotional tuning — and an outsized emotional expenditure.

137

I really enjoy your question, Maxine, about how public/private inflects our sense of enjoyment (schadenfreude?) over a bad performance.

138

Maxine Chernoff: Gabe: Small point, but I’d say that over-expenditure is a tonal issue.

139

Gary Sullivan: For me, what makes the unintentionally funny most funny is less ineptitude, and more distinctiveness. This maybe goes back to my general belief that difference & our unease or some tension surrounding it is at the root of a lot of our laughter.

140

I say this for two reasons. One is that, most of the poems at http://www.poetry.com, while almost uniformly inept, are not uniformly funny. I was poking around on the site and actually disappointed at how bland most of it was. My response was mostly disinterest. The things that made me laugh out loud were very distinct to this or that person who had posted.

141

The hardest anyone has ever laughed at one of my own readings was when I read “The Selected Blurbs and Prefaces of Robert Creeley.” There was a time when I was doing a lot of reading through various writers and discovering that I was laughing a lot at certain things which were not necessarily “funny” in the “normative” sense. But they were things that would come up again and again in a particular writer’s body of work.

142

With Creeley, it was his voice, which is so unique. It required a little manipulation on my part: I categorized blurbs or preface excerpts into one of five categories: the obvious, hyperbole, the enigmatic, emphasis, and logorrhea. I didn’t rewrite anything; I just quoted. And people —most of whom I assume love Creeley as much as I do — were rolling on the floor with laughter.

143

Here are two examples of poems from http://www.poetry.com, both responses to 9/11, and housed in a special area of the Web site devoted to these kinds of poems (of which there are currently more than 50,000):

144

Towers

As the towers collapsed

and the crowds dispersed,

a rumble was heard

as a nation was cursed.

Death by the thousands

those cowards they hide,

We’ll search the world over

both far and wide.

Then justice is served

as we watch them cry,

for God is the judge

his wrath be nigh.

145

The Puddles Inside Me

Opening myself is easy

When i do, there is a fragment of each word i hold back

For i do not want to get trapped in that very same trap i was once in

The trap i just crawled out of, the one where time has past without the bait by my side

In that hole months past and you were there for the best of times and of course the worst

Now that i have crawled out, i’m free again from the same trap until...

another bait comes by

I sense that trap near me, should i go for the bait anyways?

Sitting here caught between night and morning

While every second goes by. a tear drops not from my eye, but from the inside

Where the puddles hides from all their eyes but yours

Inside those puddles are hate, love joy and something is missing...

Its locked from even me, someone has the key...

I’m now caught in this trap again

Remembering every moment with yu makes me want to go again

Then why am i so relentless

The puddles inside are going to flood, where will they go

Only one will know

146

There’s nothing funny about the first poem, which is, we will all probably recognize, not a very good poem. But the second poem is, to me, completely, outrageously, hilarious.

147

Now, one could argue that the second is funnier in part because it’s more inept: the first person at least can rhyme and break stuff up into stanzas of equal line-length, focuses attention on the event and her reactions to it, and doesn’t misspell a lot of words.

148

And I’d agree with that. But, too, the first one is much more an attempt to write a conventional poem, whereas the second is more a poem meant to be one’s own response; it hasn’t been shaped into that-which-is-socially-recognizable-as-a-poem. And it doesn’t directly reference the events. It’s more of this particular person than the first one.

149

Much funnier in the second one than any of the misspellings is the particular way in which the writer is obsessed. All that stuff about crawling out of the hole and then being “baited.” It’s so unique to this person, to this instance of expression.

150

So I would say that, in addition to a good level of “ineptitude,” what makes something unintended to be funny funny has a lot to do with how much it can be read as a distinct instance, or of a distinct person, or mind. There’s nothing distinguishing about the first poem: anyone could have written it. “Ineptness” is, in fact, a kind of marker of the individual.

151

There’s nothing “inept,” in other words, about conforming. So “ineptitude” might be seen as, generally, a mark of difference.

152

Ange Mlinko: I’m not really sure why we’re placing so much emphasis on unintentionally funny (inept) poems. It seems to me a case of condescension. Because what we’re really doing is laughing at someone’s stupidity. When that stupidity is enshrined by the powers that be, it enrages me. I remember back in the early 90s an essay in the Hudson Review or some such place gently criticizing a Mary Oliver poem for saying something patently nonsensical; the poem was “about” the “cruelty of nature” in context of a two-headed kitten. Yeah, you can laugh now, but this is a Pulitzer Prize winner, this Mary Oliver. So, I mean, mastery of basic logic is not required to win a prize in poetry, we know this.

153

Well, Gary, you don’t convince me of the humor of ineptitude. I will second you about the utter genius of your parodies of Creeley, Silliman, and Corbett. I think you should republish them; they’re just as funny and relevant now.

154

On Jordan Davis’s blog a few months ago I took note of this:

155

I’d forgotten Palmer’s sense of humor: “The rats outnumber the roses in our garden. That’s why we’ve named it The Rat Garden.” I suppose not everybody needs some kind of acknowledgement from the poet of our shared experience — a hostile critic could describe humor in poetry as a kind of sentimental contract with the reader — but isn’t that one of the great undecided literary battles of the last century?

156

I just loved that “a hostile critic could describe humor ... as a kind of sentimental contract with the reader.” I mulled that over for a long time, because it seemed to encapsulate the ways in which a poet’s stance toward humor encapsulates their stance toward humanism; and in a time where humanism is deeply suspect, it makes sense that only very aggressive humor is allowable in the avant-garde. There is a kind of humor that dehumanizes, after all. A gentle humor; a mere wittiness or lightness; an acknowledgement of the “contract”; these are humanizing and humanistic things. So, already, retrogressive, yes?

157

George Bowering: [quoting Ange]: “I’m not really sure why we’re placing so much emphasis on unintentionally funny (inept) poems. It seems to me a case of condescension. Because what we’re really doing is laughing at someone’s stupidity. When that stupidity is enshrined by the powers that be, it enrages me.”

158

I don’t understand the point here. When is stupidity enshrined by the powers that be? I mean outside the White House.

Ange Mlinko and her son, photo Steven McNamara

159

Ange Mlinko: I return triumphantly to give you the Mary Oliver poem. I don’t recall the exact nature of the reviewer’s criticism of it; I think, though, that we can discover it on our own.

160

The Kitten

More amazed than anything

I took the perfectly black

stillborn kitten

with the one large eye

in the center of its small forehead

from the house cat’s bed

and buried it in a field

behind the house.

I suppose I could have given it

to a museum,

I could have called the local

newspaper.

But instead I took it out into the field

and opened the earth

and put it back

saying, it was real,

saying, life is infinitely inventive,

saying what other amazements

lie in the dark seed of the earth, yes,

I think I did right to go out alone

and give it back peacefully, and covered the place

with the reckless blossoms of weeds.

161

D. A. Powell: And then she covered the whole scene with reckless writing.

162

K. Silem Mohammad: OK, shoot me, but I think this is really sad and touching. I could have done without the “reckless blossoms,” but ... no, that’s the point, isn’t it, that the kitten too is one of the reckless blossoms.

163

Can you tell I’ve been teaching too many student workshops? An unseemly tolerance swells within me.

K. Silem Mohammad, photo Anne Boyer

164

George Bowering: Okay, I have to admit that I had never heard of this Mary Oliver person; but if that is an example of her poetry, I have to say that it is just really so far from an able poem as to be not funny but just pathetic. Was she trying to be funny, do you think? If so, she should have made some smart mistakes.

165

D. A. Powell: She’s apparently very good friends with John Waters. Perhaps she’s being

intentionally bad in the way that Waters’ early films (Desperate Living, Mondo Trasho, Pink Flamingos, et. al.) were intentionally bad.

166

I spent a couple of years writing intentionally bad poems, and I know that Dorothy Allison has been doing this recently as well. It’s liberating to sit down and willfully make a poem as awful as possible. And the results can sometimes be funny.

167

Ange Mlinko: I guess I only posted that Oliver poem to indicate that such a poetry, a poetry of ineptitude if you will, lies at the heart of official verse culture, and is not an anomaly. A confused metaphysics (“life is infinitely inventive” but, uh, it was stillborn?) combines with a hushed reverence in the face of nature (awe is beyond critique!) to give us decadent transcendentalism.

168

Or, I posted it to give you a good laugh. (Kasey, you are perverse.)

169

Gabriel Gudding: I’m also uncomfortable with the poetry of ineptitude label — there is a side to laughter that’s denigrative, that’s about the put-down. Thomas Hobbes called it a feeling of “sudden glory.” And he said (this is in Leviathan) that those who feel their own incapacity the most will also laugh the hardest at others. I think in some ways that’s true, but Hobbes was mistrustful of all laughter, it seems like. So, not sure Hobbes captures entirely why we laugh at someone else’s incapacity or their being brought low; I also think we laugh when a poet attempts a mood of sermonizing gravity and solemnity and they go overboard, like Oliver, Olds, or [the pieces I published] — and for me it’s like I’m laughing at outsized expenditure, like watching someone bid on a hamburger while wearing sunglasses and a cape.

170

Would just add another reason I’m uncomfortable with labeling the above inept: in official verse culture ineptitude implies something like “failure of craft,” as if ineptitude were merely an issue of technical insufficiencies (like an imbalance in metonymic logic or heavy-handed sonic counterpoint, etc.) — and not this issue of balanced emotion. I wonder if that’s the reason Kasey thinks the Oliver poem is okay: its movements and pacing and figurative aspects are okey dokey but it’s just out of proportion emotionally? Wait, Kasey said he felt its sadness. A cyclops kitten is kind of funny and sad. For me tho a lot of solemn hay is being made on its little eye.

171

The thing [about] Oliver’s poem or any poem that tries to froth into solemnity: at a certain point that solemnity can become an emotional grandstanding, an emotional monolog, a kind of pose whose purpose is the aggrandizement of the speaker/writer. It’s always, for me, at base an emotional lack of proportion (proper emotional geometry) — and comes down to something quite simple and felt with very real communal effects.

172

There is a kind of satire called menippean satire, or anarchic satire, in which you can’t tell what’s not being satirized, as if the very way a society thinks or is as a culture is being satirized — like in Erasmus’s Praise of Folly — but there’s always, too, a sense of the author loving some aspect of the society s/he’s dissing. Like in Erasmus there is a sense of deep appreciation for the energy behind everybody’s foolishness.

173

Ange Mlinko: Gabe, I just want to say I think you’re right on about emotional geometry, but I do think it’s a matter of craft too. I don’t think they can be separated. I think the poet’s job is to get certain intangibles right, like tone, register and emotional scaling.

174

K. Silem Mohammad: As far as the distinction between aggressive/belittling modes of humor and gentler/kinder modes, I don’t think there’s any satisfactory answer to this problem. What’s funny about “bad” poetry definitely has something to do with the fact that it’s “wrong” in some way to laugh at the poet (that it might hurt their feelings, that it betrays a perhaps unwarranted sense of superiority, etc.). It’s funny because you’re not supposed to laugh at it, for whatever reason. Does this relate to ideology? Sure, everything does. But I don’t think inappropriate humor is any more or less ideological than anything else, or that it is ideological in some specially coded political way (a way that is categorically different from the way ideology informs, say, nature poetry or war poetry or impeachment poetry or whatever).

175

By somewhat the same token, although Ange thinks I’m being “perverse” by finding the dead one-eyed kitten poem moving, I really don’t feel that I am: you either think poems about dead one-eyed kittens are sad or you don’t. Craft has something to do with it, but not that much; try, for example, to imagine a poem about a dead one-eyed kitten that would “succeed” in a way that would satisfy most detractors of Oliver’s poem. Those detractors may claim that the problem with the poem is that she is “inept,” whatever that might mean, but really I’m willing to bet that most of the time their problem is that she wrote a poem about such a subject in the first place. We mustn’t have sad poetic feelings about dead kittens. It’s “melodramatic” (see David Larsen’s excellent piece on melodrama as a vehicle for social shaming in his The Thorn (Faux Press 2005).

176

The line about nature’s infinite inventiveness, by the way, strikes me as ironic, as does the idea that the dark earth might hold other such “wonders.” Maybe Oliver was being “straight” with those lines, in which case she’s definitely very confused. But either way, it triggered a response to perceived irony on my part that constituted the most moving part of the poem. I have to say, I have no idea what the anti-ironists out there are talking about when they say that irony is some kind of escape from feeling feelings. Some of the deepest feelings find their most poignant expression through irony. And that seems pertinent to the question of humor as well. Even if Oliver’s poem makes us laugh (and I confess, I did laugh when I first read it), that laughter is an index of some tension, some discomfort, and as such is an important signifier in and of itself. As is its “appropriateness” or lack thereof.

177

Rachel Loden: [quoting Kasey]: “We mustn’t have sad poetic feelings about dead kittens. It’s ‘melodramatic.’” Unless of course those sad poetic feelings are blown sideways as in Ashbery’s “Our Youth,” a very poignant and romantic poem (“The dead puppies turn us back on love”). So it’s not the dead kittens per se, is it? It’s the preciousness of Oliver’s speaker, her self-dramatizing pleasure in what she wants to bury.

178

So I agree with Kasey that “Some of the deepest feelings find their most poignant expression through irony.” In the hands of someone like Ashbery irony is exactly the lance that drains the boil of sentiment and, paradoxically, lets the poignance through. But I think so many of Ashbery’s children don’t understand this and so their poems can seem arch and posturing. And (reading them) the knock on irony as a horror of feeling is easier to understand.

179

Gabe, you said something ten days ago that puzzled me: “The emotional context of a poignant work can just as easily be cut adrift of audience expectations as a comic work.” The comic predicaments in your own poems are endlessly poignant, so I can’t imagine that you want to oppose humor and feeling. Say more?

180

Gabriel Gudding: Thanks, Rachel. That was in response to the idea Ron (seemingly) furthered (in the “wink” piece) that there was/is something inherent to comedy that causes it to age faster (lose its cultural context faster) than other — heavier — modes. That strikes me as incorrect. I think immediately of Commedia dell’arte performance troupes: they flourished across Europe from the 16th to 18th Centuries — and we see the same plays still acted, the same scenes, the same characters. In fact, Saturday Night Live is basically Commedia dell’arte. What’s more, these plays stretch back into Rome and Greece, Plautus, Menander, Aristophanes: the same characters, concerns, complexities and problems inhering then as now. Same/Same.

181

And I am, yes, really suspicious of those who declare the more bourgeois modes of high seriousness and tawdry suffering are longer lasting and more culturally relevant than more comic or tragicomic modes — because (1) that assertion defies the facts of literary history (it just ain’t so), and (2) it furthers the ancient suspicion held by Official Culture against the comic mode — and belittles it into the bargain.

182

So my point was that, if we are going to cut the two modes apart and play them against each other, the relevance of laughter and detachment is in fact, historically, probably much stronger than the relevance of weeping and solemnity — given (1) that its need is stronger (that the comic mode is a “healthier” mode, spiritually speaking), and (2) that we can still laugh at The Lady’s Not for Burning or Much Ado or The Clouds or Lysistrata but I don’t find myself getting really teary or enraged or anxious at Hamlet, Macbeth, or even Patton. And I’m not much moved by Milton’s epics either. I think: hey, great language. But I’m not that moved. Whereas if I read Hero and Leander I will in fact find it both funny in places, and deeply sorrowful. Or Don Juan. And I am much more invested in the sadnesses inherent in those comic situations. (And by the way, I think Flarf is essentially the dramatic mode known as “farce” but relayed into a lyric structure.)

183

The point is — and this goes to your question more thoroughly: there seems to be more emotional range inherent to comic works, whether it’s recent dead or old white guys, the comedy and sadnesses in Ted Berrigan or in John Berryman as opposed to, say, the ever-dour and “dignified” Richard Wilbur or Robert Lowell (which seem ever to play on the same two notes: suffering and the elegiac). (But there’s also a class issue: high seriousness is about, often, money and prestige — and who gets to emote, who gets the privilege of wailing.)

184

The more thoroughly something stands in the comic mode, the more thorough the mix of laughter and sadness. You don’t get that mix in “heavier” modes — and that’s why, I feel, those modes are ultimately less relevant and more ephemeral.

185

Gary Sullivan: [quoting Rachel]: “Question for anyone: will it actually be harder to get the jokes than any of the other references?” If I remember correctly, one of Ron’s examples about the wink had to do with an ironic statement made by Stein at one point, and his concern that the irony did not carry across time. Another example was a poem by Walter Arensberg, “To Hasekawa”:

186

Perhaps it is no matter that you died.

Life’s an incognito which you saw through:

You never told on life — you had your pride;

But life has told on you.

187

...and suggesting that, the reference having been lost to history, the poem itself is flat. I actually agree with that. It reminds me of the Pound stuff I posted, but the Pound is much better written — even though I don’t like that kind of humor so much, I appreciate, say, the thing about Chesterton more than the above. (And, while I was reading a lot of Chesterton & his contemporaries at one point, and I get the reference, I think what appreciation I do have of Pound’s poem has more to do with the level of writing, which is just much stronger, more torqued, more happening, even though it’s half as long.)

188

But one thing that is missing from Ron’s critique is an acknowledgement that poetry lovers — at least a good subset of them — have never had a problem with arcana; in fact, that seems to be a part of the draw for some. Maybe even many. There are plenty of people who may read Stein’s ironic statement and be freaked out, but if they’re really poetry lovers — the kind I’m thinking of, anyway — they’ll probably dig around and ultimately come to some understanding of the situation in which she wrote it, and how it was originally meant.

189

I always liked Maya Deren’s statement about poetics: it’s a vertical, as opposed to horizontal, art. She meant, largely, emotional as opposed to narrative, but I think it goes further than that. In poetry, multiple time periods, cultures, geographies can seep into a single work. Much Chinese poetry written across the ages relies on a reader’s knowledge of, or willingness to accept, writing in the present that reaches down vertically into history.

190

Think, too, of the Spicer/Duncan gang. How much of that work is steeped in arcana. I spent several years reading almost nothing poetry-wise but Gerald Burns (not to be confused with Bruns), whose writing was steeped in — of all things — long-forgotten lit crit from the 18th & 19th century, as well as a lot of philosophy, art history, blah blah blah & so on. But a lot of stuff that had been forgotten, in addition to some stuff that is still read. I loved reading him. I still love reading him, although I’m no longer dutiful about checking many of the references.

191

Why do readers in the U.S. love Sei Shonagan so much? I think because it is so steeped in its period and place — you almost can’t get more self-contained than 10th century Japan — it makes that world come alive, at least in our imagination, even if we haven’t a clue as to all of the various social facts that are being referenced & navigated in it. And that’s largely what that book is about. Navigating that particular — to us, totally foreign — social sphere.

192

I think the problem with Ron’s [blog] statement might ultimately be that his emphasis is on the problem of reference and time (or culture), which is not really a problem for any poetry lovers I know of, or have read about in history. The real problem, with the Arensberg, is just that it’s not well written. It doesn’t matter if it was meant to be funny or poignant or scary or sad or whatever. It’s just flat writing, period.

193

Too, Ron emphasized cultural shifts in how things — or in the kinds of things that — preoccupy us. He talks about the anthology that the Arensberg poem was printed in, and mentions that it doesn’t include Loy or Stein or the Baroness or others we may appreciate today. Those lacks may have been simple literary or interpersonal politics and/or a conservative take on poetry, I don’t really know.

194

Ron does say too few people today don’t understand that, Ginsberg, say, was essentially a kind of satirist, but here I think that’s more a question — I mean, maybe the readers he’s thinking of are too young and/or not well read enough at this point to fully appreciate, or maybe just aren’t smart enough, period, to ever get it. I don’t know. I don’t agree, though, that Ginsberg at this point is being read much differently than he was in the 60s.

195

Of course time definitely does change how we read anything. Still, we all seem to laugh with Aristophanes centuries later, and while our first reading of Swift’s Modest Proposal might freak us out, most of us figure it out.

***

196

Rachel Loden: I noticed that no one answered the question “Why are you funny?” So let me try to rephrase it a bit more delicately and hope that everyone will take some sort of crack at it.

197

How did comic elements enter your work, if they did, or were they always present? How does humor function in your writing? What work does it do? Were you surprised by the entrance of the comic and why do you think it turned up in your work at that time and in that way?

198

Ange Mlinko: Well, after a very conservative college education, my re-education in my early 20s, catching up on contemporary poetry, led me to a milieu where Robert Duncan and Jacks Spicer & Kerouac were worshipped; where U Buffalo had great currency; etc. So it took me a while to find Bernadette Mayer, and that’s when I wanted to be funny — to be like her. I wanted to write a hundred “The End of Human Reign on Bashan Hill”s.

199

I still do, in fact. When I fail to, it’s because I find it’s getting harder and harder (as I grow older) to achieve that sublime silliness. I miss it.

200

Sometimes I still wish I could write Ashbery’s “Daffy Duck in Hollywood” or his Popeye sestina, but what Mayer’s work did was show me that you could write directly and personally and still have sprezzatura, still make language central.

201

Maxine Chernoff: On being funny: There’s something about my brain (pre-frontal lobe?) that predisposes me. I’ve noticed around other more somber people that it’s an existing characteristic, as basic as having black hair or hazel eyes. So naturally when I chose to write, my tonal register (emotional thermostat?) was already set. In short, I can’t help it, though I’ve expressed it differently in various forms and genres and sometimes argued with it in my later work.

Maxine Chernoff, photo Paul Hoover

202

Gary Sullivan: It’s probably impossible to separate “the comic” out from my work and look at it as a separate element. Even when I was in grammar school I was always drawing cartoons and getting groups of kids together to perform comic plays I had written. I was nearly kicked out of high school for publishing an underground humor magazine, Retch. At the time I was reading a lot of the National Lampoon, Lenny Bruce, Robert Benchley, Woody Allen, James Thurber, Terry Southern, Richard Brautigan, and listening to Nipsey Russell and Firesign Theater. I gravitated towards this stuff even when I wasn’t getting the jokes: I think it was a recognition of similar world-view.

203

I studied music composition in college, but would spend a lot of time playing 33-1/3 LPs at 45 or 78 or playing, say, Beethoven’s 9th Symphony simultaneously with some pop record, and doing other fairly silly things to “subvert” what often struck me as relentlessly serious work, and the often oppressive art-historical narrative that supported it. What few compositions I wrote tended to take the rules we were being force-fed, such as “melody ascends,” and writing a melody that descended.

204

Ultimately, I abandoned music and studied theater writing, concentrating on farce. I basically spent three years studying the history of comedic theater, from Aristophanes, Plautus, and Terence up through Wallace Shawn, Christopher Durang, Tina Howe. But I most liked Beckett and Ionesco. I also studied Pope & Swift et al. around this time.

205

After college, I drew comics for the weekly paper in SF, was in a comedy troupe, and wrote farces and comedic monologues that I and/or my friends, mostly non-poets, would perform.

206

My poet friends at the time, especially George Albon and Dan Davidson, turned me on to poetry by loaning or recommending books they assumed I’d like: Bean Spasms, Circus Nerves, A Nest of Ninnies, The Duplications, Mayer’s Utopia, etc. A lot of New York School stuff and some language writing, too, especially Charles Bernstein. On my own I somehow discovered Philip Whalen, Paul Blackburn, Gertrude Stein (who may have actually been a George recommendation), Jerome Sala, Mina Loy, Ron Silliman (BART was the first, which I loved), etc. I also learned to appreciate, if not fully embrace, poets like Charles Olson, Jack Spicer, etc. I probably started reading pre-twentieth-century poetry around this time, falling most heavily for the Earl of Rochester and Ben Jonson.

207

I studied comedic writers in the same way I studied poets: looking for how lines or sentences were constructed, how images were used, how shifts in tonal register were done, and to what effect, as well as focusing on how various people used assonance & dissonance & rhythm & emphasis & so on. Most illuminating of the non-poets were Terry Southern and the Firesign Theater, from whom I stole dialog or monologue pacing. How they would even use throwaway stuff, like “ums” or “ahs” or whatever, to create more fully torqued writing. (“Ah ... Clem.”)

208

I was never interested in topical humor. I tended to respond to non-sequitur, torque, and juxtaposition on the formal end, and embarrassment, awkwardness, and shame on the social end.

209

A lot of the poems I’ve done lately, generated from misspelled words, for instance, seem to make people laugh, and although I do smile when I’m writing them, I’m not laughing at anyone. My impulse to do those comes from ideas I have about the piano and the printing press — the standardization of scale and spelling — as flattening devices, and my laughter comes from the delight of watching fairly simple, everyday language unflatten.

210