JACKET INTERVIEW

George Bowering

in conversation with

Rachel Loden

This interview was conducted in the Northern Spring and Summer of 2006.

This piece is about 24 printed pages long

1

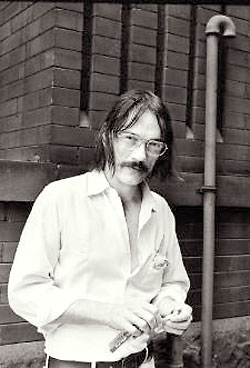

George Bowering, 1970. Photo by Sheldon Grimson; permission: Maryrose Coleman of the Prime Gallery.

paragraph 2

George Bowering: I know that it sort of looks as if it is mimeoed, and maybe it might as well have been, but it was produced by way of the offset system that was fairly new at the time, a primitive (even then) version of it that I had learned with my pals in Vancouver when we were producing Tish, the poetry newsletter. We broke up and went our ways after the spring and summer of 1963, which was also, coincidentally, the time of the great poetry summer school at UBC, where Allen and Peter had just come straight from Japan, and were there on “Faculty” with Olson and Levertov and Creeley and Duncan and Margaret Avison. We Tish guys just took this as oh yes, this is the way we grow in poetry, though there were people at the time who pointed out that all these people had never before been in the same city, never mind the same room. Well, it had been wonderful luck that there we were all at the same time at UBC those years, and there when Warren Tallman had got a job there, and Ellen Tallman was a school friend of people like Lamantia and McClure, and knew Duncan and the crowd well, and then of course, along came the Allen anthology in 1960, though I think that I had seen it in 1959, and the first books of Olson and Creeley and so on, and On the Road was only a couple years old. Very very heady times, and the same thing happening in Canadian publishing at least, with Contact Press etc. back east. I mean, this is how I knew Margaret Randall, because there were magazines exchanging with one another, so we at Tish got a mailing list from LeRoi Jones and Diane DiPrima, their mimeo mag, and later we would get a request for our mailing list from John Sinclair and crew in Detroit, and so it went. There in MexCity was El Corno Emplumado, and so a meeting place for LatinAmerican poetry and Gringo poetry, so that when Angela and I went to Mexico in our Chev in the summer of 1964, it was natural that we stayed at Meg and Sergio’s until they found us a place to live in the neighbourhood, and I started meeting the Latino poets I had been reading, because they came to MexCity too.

George Bowering

3

So when the run of Tish and all that went with it was over for us first-round guys, we all went our ways. Frank Davey went to USC. Fred Wah went to New Mexico. I went to Calgary. Jamie went to San Francisco. Frank and Fred and I all started poetry magazines, and mine was Imago. I was particularly interested in long poems and parts of long poems —hence every third issue was a poem by one person. The shortest segment of a long poem that I ever published was a little bit of Olson’s later Maximus stuff.

4

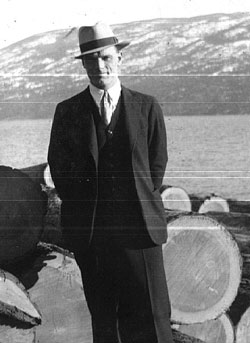

Ewart Harry Bowering. Photo by Pearl Bowering. Permission: George Bowering.

5

Maybe I was being a little dramatic. Maybe.

6

7

Well, yeah. He was missing most of his right index finger, from an accident with a saw. That’s why I, in copying him, learned to type with my middle fingers, and squeeze with my middle finger when firing a .22 rifle etc. Well, I know you didnt mean this sort of thing; but I couldnt resist.

8

Ewart Harry Bowering, 1937. Photo by Pearl Bowering. Permission: George Bowering.

9

I dont know. These arent questions I have exactly asked myself; and even if I do now, I dont know how to make a real answer.

10

In one sense it was neat to have a really smart dad living a kind of ordinary life in a small town. He certainly set an example for me. I get just as pissed off as he did when he confronted bad English usage coming from a source that is supposed to know better. I think I have my daughter doing something like that. It wasnt as if he sat around in our house (most of which he built) reading Horace. There werent a lot of deep books in our house, and this is one area in which I was determined to get past my environment. My mother, who is still alive, is a small town girl, made it through high school and is pretty smart for a small town girl, but she doesnt have much of a clue about what I write, though she has all my books. My father was 9 years older, and smarter, but he was a good friend to her, and she still talks to him 33 years after his death. He played cards with her, played badminton with her, late in life golfed and curled with her. They did gymnastics when I was a kid. They would both be reading all the time. It wasnt highfalutin’ reading, but it was reading, so I got the idea to be reading all the time, and then later I found out that it might be a good idea to read Horace. My kid reads all the time. I remember being happy to see her spend her allowance on a Robert Creeley book when she was a teenager. I have found out since that this is not normal to all teenagers. If my father had managed to live to be old, I might have shown him some books I had written.

Pearl and Ewart Bowering. Photographer unknown. Bowering family collection. Permission: George Bowering.

11

12

13

14

Jeeze, I feel as if I am “in group,” which I managed to avoid during the Fritz Perls era.

15

Well, yes, a Puritan, a version of which [Bowering’s wife] Jean calls me when she calls me “Depression Boy.”

16

I did not manage to go to a Baptist church or Sunday school when I was a kid, because there wasnt one in Oliver, my small town, so I went to the United Church Sunday school. The United Church had been formed when more progressive Presbyterians and Methodists got together way back when. Now it is the most liberal church in Canada, I guess, if you dont count the Unitarians. But though my Grandfather had been, before my lifetime, a Baptist minister, and in fact a converted from CofE [Church of England] Baptist to start with, my parents did not go to church. But my mother certainly kept reminding me of the principles, thrift, humbleness, and my father let me know about honesty, take back the comic books I had lifted from the Rexall Drugstore and apologize, etc. In my second history book, the one about the Canadian prime ministers, I praise the second PM, Alexander Mackenzie, for his honesty and his humility etc. He was the only PM then who refused to be made a “Sir.” And he was, notably, a Scottish Baptist puritan. He was a true democrat, a Christian who saw that a Christianity demands democracy and social planning. I point out that puritanism and democracy are intertwined. This is puritanism, real, not that stuff the haywire US (and some Cdn) churches preach, not that suggestion that one should murder socialist presidents, etc.

17

If a so-called puritan allows moral smugness to creep into his character (a thing people hate about puritanism), then he/she has departed from puritanism.

18

What about poetry? Well, a puritan shouldnt use similes, eh?

19

20

Oh yes. I never believed Blake, I realize now, about excess. I have tried and tried and I can’t make myself like the French symbolistes. I mean, I read a collection of Mallarmé recently, but couldnt really get with it, though I quoted him on the last page of Caprice. Yes, Creeley, and not just in the form of the verse, but also in what he says there. I covet a pair of those new running shoes that everyone else has had over the past 20 years, but I still have running shoes I bought at a sale in Seattle in the eighties, and so they arent worn out yet. So writing. There is very little poetry that I look forward to reading as much as I do Creeley’s. So his last collection is coming out next month, and I wait and wait. Yet I would never write to the publisher for the galleys to review or something. I want that fresh finished book. See. Stone cutter. Yes, not flower strewer. I am very very fond of Ron Padgett’s poetry. The straight ahead, the sunny economy. He saw the plain remarks of O’Hara and Koch and Elmslie, and made his own, the best of all.

21

Ewart Harry Bowering, 1936. Photo by Pearl Bowering. Permission: George Bowering.

22

No, not the sportswriting. I taught myself sportswriting by copying what the famous sportswriters did, and that amounted, for one thing, but a big one, in saying things in some other elegance. Like if you have mentioned a home run, you have to find another way of saying it: “The lanky Oklahoman unleashed the power built into those huge arms over the years on the ranch, and stroked a Ruthian clout over the left field barrier.” Nope. If there is pith or pithiness (“oh look, ma, Billy just pithed on my poem!”) it comes from William Carlos Williams and the Imagists and maybe Creeley and maybe Cid Corman. Or if it is Creeley, of course it is puritanism anyway. Or maybe it comes from reading hundreds of westerns when I was a boy, in which refusing to be ornate in language was a virtue, what separated one from them easterners or rich folks or crooks.

23

24

25

26

I did write an essay on Avison regarding her take on Jesus the artist. But really, I don’t think that I take him as a model regarding poetry, art, creativity or whatever that is, though when you use that word, it gets tempting. But I have always tried to avoid that word, saying that artists are more like arrangers than creators, which can be seen easily in sculpture, and in the other arts. I used to say no no, only the God proposed in our religions can be the creator. I was an arrogant puss, but just the same. . . . As to Christ or rather Jesus as a model for being a human person, there was a lot of that, especially in the early days. When I was about 5 I thought there was a chance that I was Jesus come back. But around then I also thought I might be the first human to live forever on earth. I also thought I might have a super power or two. Well. Until I was 21, with declining hope, I used to pray. Not after that, except once, when I was driving home after taking Angela for one of her big cancer operations.

27

But in general I like the idea of Jesus a lot. I hate what the US right wing pro-ignorance fundamentalist preachers and believers have made of him. I mean Jesus was a natural lead-in to socialism, and down there they connect him with capitalism. Well, they do that in US-oriented churches in Alberta etc. too. I thought that Jesus was a kind of reform or correction of the old testament prophets and kings, that he was for tolerance and self-forgetting decency and all that. He hung out with 12 men and a prostitute. Chances are he was living a Gay life-style, though they didnt have lifestyles back then; and those redneck churches hate homosexuals. I still call myself a Christian, though I don’t go for the rules, everlasting life as a result of the choice to believe, etc. I mean it in a confrontational way, usually, to distinguish me from George Bush, for example. The life of Jesus as a metaphor, as an example. My Jesus, when I was a kid, was pretty Buddhistic.

28

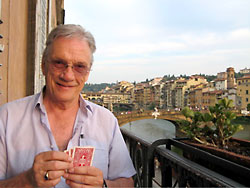

I dont go to church, except when I am visiting Italy or some such place. I go to churches, art galleries and palaces. I am sometimes there when a mass is being celebrated.

Bowering by the Arno, on his honeymoon with Jean. Photo: Jean Baird. Permission: Jean Baird.

29

30

Well, thank you for saying so.

31

32

If I did some deep research in all my papers etc. I might find some exact dates and so on. But Jeeze, Rachel. . .

33

But there are some things to be said maybe about Rilke. It turned out a couple decades back that there were a lot of Rilke freaks in Vancouver, including the woman who was his translator into English, well, one of them, maybe the official one. Was she also biographer? Oh, I’ll be vague. There was Karl Siegler, now publisher of Talonbooks, who is a genuine Kraut, did a translation and book of Rilke’s Sonnets, had the launch party at giant Bowerings’ house, with photo montage made of the event by Roy Kiyooka, now where did that go? Blaser was talking about him. Etc. etc. etc. So when I went to Trieste in late 1977 to start writing a novel, I went to Duino, but you couldnt get in because some manufacturer millionaire owned the place and kept the gate closed. But you could walk along edge of cliff overlooking the Adriatic and Duino Castle, and so I did, knowing that Rilke must have walked it, and it was a path made of limestone stones, so I brought 11 of these home to Vancouver, and distributed them.

34

Also, of course, I had been to the lectures that Jack Spicer gave at Warren Tallman’s house in 1965, a house that was 2 doors from where I would later live, see above, and of course Jack was on about dictated verse, with main models being Rilke and Yeats. So a lot of Rilke in the air. And of course I believe in the idea of verse as given by an inspirer, muse or ghost or whatever, but not subconscious, though I can see how that would do it for some people.

35

But I didnt like Rilke all that much, partly because he mooched off rich women, but mainly because he is namby pamby or is it airy fairy, well, gushy and all that European lack of restraint. But there I was.

36

I decided to do a translation of Duino Elegies, partly because Trieste (which Rilke didnt like) was my signature city, partly because of the dictated verse idea. I was starting off on a strange tour, aegis of the Canadian External Affairs dept., so I was seeing some Canadian consulates etc., but I did readings and talks in Dallas, Santa Fe, Phoenix, LA, San Diego, Mexico City, stops in Albuquerque, Tucson, etc. I decided to write, while on this trip, the beginning of a translation of Duino Elegies into English (not sure when the Kerrisdale idea came), and do it that way, you know, with a language you don’t really know, but you take guesses, and come up with some kind of creative translation.

37

So I started on the plane trip from Vancouver to Dallas, and continued after a day at Dallas, during which a former Dallas Cowboys Cheerleader kicked me in the ankle at the Cdn consulate, because I said I didnt like either the Cowboys or football. There in Dallas they thought I would like to see the house where that famous TV show was filmed, about who killed ER or whatever, Ewing, but I had never seen the show. I asked to see the site of the Kennedy killing; they couldnt understand why I might want to see that. Anyway, next day I was flying to Albuquerque, and decided to scratch out whatever I had written and didnt like. When I got to New Mexico, I had scratched out the whole page, every word.

38

Well, of course I had my copy of the Elegies in German with me, and I was sitting in a little student kind of coffee place in Santa Fe, reading them, and at the next table there was a young man sitting there reading Rilke’s Sonnets to Orpheus. So I knew I wasnt supposed to quit. So I dropped the idea of the guesswork translation, and started translating with the help of a number of English translations, and kept my mind clean by reading French poetry as I went along.

39

After the first run of ten, took about 6 months, I had notebooks with my version in long long lines, like Rilke’s. It didnt sound enough like the way I hear poems, and I realized that translation had to be more than finding English words for German words; it had to include finding my 1980s poetics, notation, to translate from his long rimed lines. So I worked them over, and wound up with a book I felt most mine of all, serious, musical.

Kerrisdale Elegies, 1984

40

41

42

Funny you should ask. At the moment I am looking at my diary for the period of the Summer 1963 poetry fest at University of British Columbia, Olson, Duncan, Creeley, Ginsberg etc., with a view to publishing it somewhere. It isnt all that interesting, but there you go. Also, I am writing a chapbook poem gathered from the long on the fly travel book I wrote in Europe, 1966. Such digging. But to answer the main question: no, yr not likely to see the diaries en toto. In fact, they will go to the National Library of Canada after my reluctant departure, but I dont predict their publication after that—though who knows? I mean if Charles Bukowski could get his poetry published, I guess anything could get published. The only surprise I can imagine arising from my diaries would be in the discovery of their dullness for the most part. I mean, come on, this guy entered his bowling scores!

43

44

I have done quite a bit of that, what with details re my birth and a few titles of books and so on. I don’t want closure, you see.

45

46

47

48

49

Well, the puritan bit was certainly there, and I think that it was mixed with a fear that time wasnt long enough. But I have also always been lazy, I think. I often tell people that I publish more than I write. Though I do have a number of unpublished books, such as the travel book 1966 I am reading now—we are in Istanbul. I seem to be avoiding this question. Well, laziness. I do get up late, and I do tend to not want to write and work, though I also have each morning a delicious feeling that there is writing to be done—too many jobs at the moment. But the main thing is this double feeling (I have double feelings about a lot of things)—that I am both lazy and hard-working. I have learned to say no to some requests for writing, even when offered 400 bucks for a poem as I was recently! Anyway, getting back to that CW course—I was, I guess, a desultory writer before then. Then I had an assignment every 10 days, so there was no way to sluff off.

50

51

Oh, it’s that I have a big book of poems coming out in Sept., and have been writing no poetry except these 12 chapbooks I am writing this year, a page a day.

52

53

Hey, in 4 days the job will be half done. Don’t worry, some revision, trimming, buffing, happens. Today, for example I did the slightly new version of three pages of the April poem, which is called “U.S. Sonnets.”

54

55

Some people could have said ah hell, and manufactured a poem or two. I thought of it, later. But no, eh?

56

57

58

59

Oh, no, I did.

60

61

Yeah, I guess so, but we have already had to get used to referring to “Ezra Kilogram,” and Frost’s line “Kilometers to go before I sleep,” and Housman’s Half-litres and litres of Ludlow Beer.”

62

63

I don’t think that I can give an overall general answer, especially now that I have written a 30pp (perfect for chapbook) poem called “U.S. Sonnets.”

64

So I will chip away.

65

I remember a few days how many years ago, spending several days in Buffalo, and then flying to Toronto. Why fly across the lake to Toronto? Well, that was the way someone set it up. In Buffalo I just talked to everyone I saw, especially in the US bars I love so much, whether they are in Buffalo or Missoula or San Diego. When I got to the Toronto airport, and was waiting for my bag to show up on the conveyor, I said something to the guy in a sports jacket beside me, and he didnt even answer, afraid of what he might be getting into.

66

It does worry me when I think about it, that anyone I talk to in the US might have a pistol in his pocket or her handbag, but I carry on, even when a little nervous. I remember walking late late at night all alone in the Alphabets streets in NYC, and in Harlem, and I guess I got left alone because I was wearing a toque, an English policeman’s cape, logging boots, electrician gloves and red trousers. But recently, walking in a strange beat look-out section of Tucson, there I was, an old guy, and I had to walk under an underpass, where four teenage black kids were smoking dope, and I said “smells good,” as I went by, and I made it.

67

I can list a lot of things I don’t like, but not here.

Bowering at the ballpark. Photo: Jean Baird. Permission: Jean Baird.

68

When I am at a baseball game, I know that a lot of the people in the stands know baseball. That aint true in the stands at the ballpark here. I dont know how that connects with what I said above, but it does. Last night I went to the jazz festival here, and first we heard a quintet of Europeans and Canadians who live in Paris playing for an hour, and it was okay. But then after the intermission on came McCoy Tyner and two other old black American men and they played loud and just tear ahead perfect American music, and I was lifted in my heart, the way I hadnt been since hearing Oliver Lake play a year ago.

69

Baseball

Jazz

Mexican food

The literary presses

70

Sitting down in a bar and grill somewhere in Wisconsin and betting the big stranger in a flannel shirt that he can’t eat four plates of ribs.

71

And paying off the bet with that funny-looking US money.

72

73

74

Well, there I was, growing up, a boy eager for print and radio talk, a few miles from the border of the great democracy that was always congratulating itself in comic books, radio shows, movies etc. And a long way from Toronto, our media centre, and even quite a way from Vancouver, the provincial big smoke. So I was thoroughly brainwashed, even without having to place a little hand over my nipple and recite a standard oath of allegiance or else. So I wanted to grow up and take out US citizenship. I mean it was a great democracy, and we had remnants of British rule, symbols only, but still, I thought that if Canadians older than I were okay with Queen stamps and so on, I wanted out. So in school I led a futile campaign against the English crown, putting notes inside library books, etc. When someone played “God Save the Queen” after a school dance, I ostentatiously went and took a drink of water out of the fountain.

Bowering at 19 with his mother, Pearl, and his two younger brothers, Jim and Roger. Photo: Sally Brown. Permission: Sally Brown.

75

76

On paper it might look worse than that. In becoming Canada’s first Parliamentary Poet Laureate I might have been seen as the Governor-General’s versifier, and thus the Queen’s toady. Well, the PL in England is maybe connected with the monarch. In Canada it is carefully called the Parliamentary PL, so he/she is associated with the Parliamentary Library. I did get one request from the GG, and I didnt do it. I did, however, fulfill a request from the Canadian Little League organization, to write a poem for the program of their annual tournament.

77

Yeah, I am aware of the irony you suggest. Somewhere, in Autobiology or somewhere, I wrote about the shift. I make a point of buying the postage stamps that do not have the Queen on them, etc. But as I grew up I saw that there were worse things to be than some kind of ceremonial extension of the former British empire, and one of those is to be a colonial in the U.S. empire. There are those in Ontario especially who say that Canada’s connection to Britain was what saved us from being gobbled up by the U.S., as Jefferson and Whitman assumed we would be. I don’t know. That may be true. But I do know this: that I prefer the Parliamentary system to the US system, in which the dogcatchers are elected and the president’s cabinet is appointed by the president. We do it the other way round.

78

I wish Canada were better than it is, of course. But I think that not being the USA is a good first step. I am so glad that we have survived four invasions from the south.

79

80

Oh no. I still support my anti-British stance of my 15th year. But I no longer believe in Steve Canyon and Captain America.

81

82

I get it. There is a term used mainly in Ontario. “Red Conservative,” meaning a member of the former Progressive Conservative Party who is socially and maybe even fiscally progressive. That party has pretty well been destroyed by more recent pols such as the current prime minister, who is from Alberta, who is not progressive, and has in fact removed that word from the party’s name. They are more like bible belt redneck Bushites. I like Peggy’s term. It is a bit of in-your-facism but also pretty accurate. I am sure that she is a royalist because she figures that the current ceremonial royalism is preferable to what has happened with being a republic.

83

As you know, some of my best friends and favourite authors are USAmericans. But here is a little factoid. Recently a friend of mine in Toronto went to her 50th highschool graduation anniversary in a suburb of Buffalo. Lynn moved to Canada in the sixties. At the reunion, she was one of the 2 white-haired people who did not swear allegiance to the flag etc.! Living up here I can’t even imagine having the notion of having such an event at a highschool reunion!

84

85

86

Yep, my mother’s father’s family was from the Ozarks, where Missouri, Arkansas and Tennessee come together, I guess, and her mother was a Mennonite from an Oregon community. (I just found out this year that her family had been in Ontario before going to the US, Michigan, etc.) My father’s father did his Baptist preacher training in Minnesota, and had been begged by a small town in Idaho to come and be their preacher, but then the church ordered him to Alberta, because in an area south of Edmonton the Lutherans were nabbing all the young men.

87

88

89

I liked it and sometimes I miss it. I am now often introduced as Canada’s first poet laureate, and sometimes they even leave “first” out.

90

91

I did like hobnobbing in the rooms of the Canadian Parliamentary buildings. And I liked talking to journalists, those folk who had not till that time shown any interest in poetry. I even liked doing interviews with the Quebec press and radio, though my French is very very slim.

92

93

Don’t miss it one bit. In fact I am reading a thesis right now, and wishing I didnt have to, but it is by an Italian woman who says she came here after hearing me do a reading in Bologna.

94

95

I liked being writer in residence at the Oliver rodeo, and at the Grand Forks International Baseball Tournament.

96

97

Oh, that is really impossible to answer. I know that in the early to mid sixties, when I was starting to publish a lot of poems, there were as many if not more in US magazines than in Canadian (and some elsewhere). Then after a while I seemed to stop publishing so much in the US, I don’t know, didnt carry out the effort. Maybe the postage got to be too expensive.

98

If there’d been no border I would probably be more resolutely a small press author, whereas in Canada I have managed to be a small press author who commits novels and nonfiction to Penguin Books etc. I was, early on, a big press poet for about 5 books, but then gave myself an admonition, and took my poems away from McClelland & Stewart and gave them to Coach House and Talon, etc.

99

100

101

102

Jouissance?

103

Yes. It is difficult to describe. Like right at this instant I am feeling a stir that will lead to inscribing the 18th section of my July chapbook manuscript. I do, like others, lots of evasions, or things you have to take care of before getting down to it. But I do like writing, even when I dont feel like it. The different forms offer somewhat different good feelings. I like the dance of syllables when poetry is the thing. I squirm in my chair. I like the daily advance of the story or novel or essay. Writing an essay is a lot like writing a story. The sentence is what you want, the sentence that is very clear but mysterious at the same time.

104

Bowering throwing out the first ball at Miller Stadium. Photo: Milwaukee Brewers Ball Club.

105

Well, last year I was invited to do a reading at University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee. I said sure, as long as it could happen while the Milwaukee Brewers were at home. They suggested the date during a game against the Cincinnati Reds. We were on. Then they went a little wild, and as the organizing between them and Jean proceeded, the Milwaukee Brewers and the Miller Beer Company got involved, so that there was a party for local poets and so on at the brewery, and the first pitch at Miller Park.

106

Then I got really sick on a trip out to see Lorine Niedecker’s home, and puked at the library and puked at the museum and could not make it to the brewery party. But did go to the game, feeling really sick, and for the 5 minutes it took to do the pitch I felt okay, so I figured hey this is Milwaukee so I ate a bratwurst, and puked it up. The organizers, Jim Hazard and Susan Firer, were wonderful with me. I also did a reading with Ammiel Alcalay at the best small press and poetry bookstore in the USA. What is it called again? Woodland Pattern.

107

The pitch, by the way, was a strike, waist high on the corner.

108

109

Ah the wedding went just terrifically yesterday, and get this: [just as bride Jean had predicted] I got one tiny speck of red wine on my shirt around 5:00.

George Bowering and Jean Baird at their wedding (at left is Dora FitzGerald, who married them). Photo and permission: Sebastian Roberts.

110

111

I am conscious of Jack Spicer’s nostrum or whatever that you should not work on 2 things at once, but in these days I find myself doing that. One danger is that I will take too long a rest from something & not get back to it. I am, for example 65pp into a YA novel, and havent worked on it for over 2 years. I am 45pp into another novel and havent worked on it since last, I dont know, Fall. But one of the books I am working on is a collection of 48 very short essays about a single word. It gives me hope, because I wrote the first three 10 or more years ago, then a couple 4 years ago, and now a bunch of them. I am 36 words in, or 3/4 done. I am also doing this other project that I am partly reluctant to describe, because people might see it as a sign of ease. I decided in December that in 2006 I would write 12 chapbooks, all different in form and subject, one each month, a poem a day, or rather a poem a month, with a page/section writ each day. Even I have been surprised at how good they are. So far Jan and Feb have publishers. I am working on the 7th of the poems, and know the subjects or methods for August and September.

112

113

That one [the chapbooks] I do know, for sure. Others, no, though I am trying to get a couple more of the words pieces done, so I will fill up a manuscript binder, so I can get to rewriting/typing another month/poem, which, at 31 pp would be too long for the binder, but the binder has to have 50 MSS in it. Hard to explain.

114

So you see. But then, I have written a number of essays this year because anthologies or the like have asked for them.

115

116

Only that I want to return to the latter of those novels, and I seem to be writing a novel disguised as short stories set in 1962.

117

118

Well, a year ago I never would have guessed that I had to write a page/section about my new wife’s body part today . . . .

119

120

Aw, whenever I felt any anxiety I just reached for some oxygen. I have enjoyed the contact, Rachel. You did give me time to catch my breath, and I was happy to have to figure out what I think about all these things. Everyone should get to do that. Thanks for helping me do it.

| |

|

Rachel Loden is the author of Hotel Imperium (University of Georgia Press), winner of the Contemporary Poetry Series Competition. Loden has also published four chapbooks, including The Richard Nixon Snow Globe (Wild Honey Press). Her work has appeared recently in New American Writing, The Hat, Zoland Poetry and Best American Poetry 2005, and she has been interviewed in The Iowa Review and Jacket. Awards include a Pushcart Prize, a Fellowship in Poetry from the California Arts Council, and a 2006 grant from the Fund for Poetry. She maintains a website here: |