The essay that follows looks past the earliest Hebraic strand of the Bible, c. 920 B.C.E., to the Sumerian poets who provided the sources for both the Epic of Gilgamesh and the life of Abraham. These Sumerian poems and their strategies of narrative and lament, dream and cosmic theater, are what the ancient biblical poets inherited and turned into characters. Recent poets as diverse as Charles Olson, bpNichol, and Alice Notley have used portions of the Sumerian poems but without digging into their actual authorship or influence on poetry in the West.

That influence comes primarily through the creative portions of the Bible and we can find it in Milton and Blake, in Duncan and Reznikoff, all of whom had serious biblical encounters. But poets today, in their reluctance to engage things biblical, have further repressed the visionary wells at which our first writing poets — and their innovative translators — drank.

What will follow is excerpted from “Contracts,” Chapter Nine of my Abraham: The First Historical Biography (new from Basic Books). It focuses upon Abraham reading to himself in the Epic of Gilgamesh, as he most certainly would have done in the 1700s B.C.E. I’ve contextualized Abraham as an educated scribe and translator in Ur and Harran, as the Bible suggests, and here he is making a copy of the Gilgamesh epic as we, the readers, “look on over his shoulder” and hear his thoughts, specifically on episodes with the man from the wilderness, Enkidu.

So this essay is, in essence, a poet’s reading of not just Gilgamesh or the Bible but the first writing poets we can identify, in ancient Sumer, circa 2700 B.C.E. For these passages about Enkidu were originally parts of Sumerian poems, which were then excerpted almost a thousand years later by the Akkadian poet who translated and condensed them into the shorter Epic of Gilgamesh we think of as a “classic” today. I contend that the earlier Sumerian poems were stronger. But how do I come to assert this?

As a poet translating the Hebrew Bible for many decades now, I am looking at a text codified less than two thousand years ago, and I’m looking through that text to the original sources, actually written down a thousand years before that. No copies of the originals survive, written in an earlier script. They would look to us now, if we can imagine the text we do have from two millenniums ago as today’s English, to be Olde English, long before Chaucer.

So I work to make the later text transparent, with the aid of much linguistic and contextual research, and read through it, down to the original written sources beneath. This isn’t as hard to do as it may sound, because the originals employ the poetics of their times and these are increasingly partial to poetic punning and internal rhyming the farther back they go. Impenetrable as this has seemed to most scholars in their academic straitjackets, it’s rather a joy to a practicing poet who may catch on to the ancient wordplay with relative ease. What seem like contradictory passages to the scholarly mind are often in fact plays on, and with, still earlier tradition by Hebraic authors such as J.

The Book of J (Grove, coauthored with Harold Bloom) described the first great author of the Bible as an educated woman. She is further embodied as a poet-scholar in my The Lost Book of Paradise and now in Abraham, where I fill out J more than ever, finding for her a precursor in Enheduanna, the first great Sumerian writing poet — and also a woman — whose life we know something about. But I’m not simply building a feminist case; instead, in sexualizing the study of authorship, I try to reopen the channels to our earliest conceptions of wildness and, even more significantly, to our devastating loss of it. That hurt starts with the loss of the original Hebraic text — the one I translate by looking through the one we have — and the lost chance of directly apprehending the Sumerian influence.

So the closest thing to this original Hebraic text I’ve been able to literally read is the Dead Sea Scrolls in the Israel Museum, which include copies of books from the Hebrew Bible, written down a few centuries before the Hebrew text we use today was codified by the Masoretes (hence known as the Masoretic text). It’s remarkable to stand in front of these papyrus scrolls under glass and read them as legibly as any book in Hebrew today, and yet we are a long way from the original manuscripts here. It is more like over 800 years to the lost documents of the author of Abraham’s life, J.

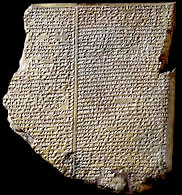

So imagine my amazement when I found myself parsing the actual 4000-plus years-old engraved tablets from the Baghdad museum of the original Sumerian poems of Gilgamesh and Enkidu. It was like a well opened up in the desert Hebrew scrolls and I could actually drink there. I had taught myself to read cuneiform script in only a few weeks of intense study, easier than learning Creole — so long as one has the aid of the online Sumerian and Akkadian dictionaries. Nor did I have to travel to Baghdad: high-contrast photos of the tablets are now accessible online, putting one face-to-face with a text engraved during the original poet’s lifetime, at least in some cases.

Clay tablet

What’s the big deal in reading the first poets to compose their texts in writing? It may be like reading Pound’s The Cantos for the first time and wondering, how did this collage composition evolve out of Browning and Yeats? But more than that, reading The Cantos grows easier for us by the year, inasmuch as collage has become integral to our media. And in the same way, we are becoming more and more familiar with the meaning of wildness and species consciousness as well as species distinctions today. The strangeness of Enkidu, the “wild man” of the forest for the Sumerian poets, was that he represented the pre-civilized higher primate at the same time as he stood for a closer harmony with nature. Already these first writing poets were conscious of the loss of natural history and their own earthly origins.

And that’s what makes Enkidu equally poignant to them as he is to us today. Eventually Enkidu becomes bosom buddy of King Gilgamesh in the translated Epic, a form of classic high comedy, but when we compare the original Sumerian we can see how the original was tragicomic. It would appear that way too, tragicomic, to Abraham reading it a thousand years later in 1720 B.C.E. For at that point he is reading a “classic” of a dead civilization, and his own is further than ever from harmony with wilderness.

Abraham took that estrangement with him as he set out for the presumed wilderness of Canaan, and that is a story that accounts in part for why the Hebrew Bible is the most deeply buried and unapprehended text in any poet’s consciousness today. For today, even if we can get past the uses of religion, ideology and brain-dead courses in “The Bible as Literature,” we can still barely see past the biblical characters. And we need to do that, in order to re-constitute the poetics upon which our current genres, traditional and modern, squat. Squat and cower — estranging us further from our original civilized wildness.

The dramatic essay that follows situates us in ancient Harran, sister-city of classical Sumerian culture in Ur, from which Abraham’s family had migrated with donkeys to breed and sell. It was Abraham’s father’s failed attempt to reach Canaan, after closing up shop in Ur. In fact it had been a workshop for making statues, and Abraham would carry on this family business in Harran for a time. We begin with mention of the city-god common to Ur and Harran, Nanna…

from Harran

This moon-god, who served as guide to journeys, held donkeys — a symbol of trade and freedom of movement — in high regard. The moon-god veneration also contributed to making Ur and Harran a center of writing: Nanna was a conduit of creativity from his father, the creator-god Enlil, and there was a close relationship between Nanna and Nabu, the god of writing. Abraham’s role in his father’s statue workshop would have included engraving the bodies of the statues with writing. The work draws one close to the Sumerian literary texts, which are combed for excerpts. The writing on the statue was an artistic embellishment, a testament to the figure’s authority. Poems like the Gilgamesh epics were choreographed as a reading with actors in the Sumerian king’s palace and also set to music — yet even in this dramatic form their effect was less momentous than the cuneiform writing on clay tablets. Writing was on the way to becoming the definitive stage.

Reading and Theater

The idea that a single person could read “to himself” — that is, to read and hold an entire book-length work in mind — was a Sumerian invention but it had already become a lost art after the destruction of the last dynasty of Ur, several hundred years before Abraham’s birth. Of course, original authors and translators in Akkadian and some scholars continued to imagine entire works, but this kind of reading was now confined to an extremely small circle in Harran. What had been common in Ur was precious in Harran, Abraham discovered.

Nothing had been more common than the scribal dictionary in the temple edubbas [schools]. Although their function was to provide the meaning of the Akkadian vocabulary, each page and each line began with the Sumerian word. Only a scribe could imagine what was lost in the literal translation; a dictionary could not do it by itself. It took a creative work of art to identify and dramatize the loss of Sumer. This is what Abraham now learned about the Akkadian rendition of the Epic of Gilgamesh. The older Sumerian version of the epic, originally a much larger collection of poems, resembled a Sumerian Bible, the written embodiment of the culture that was now both behind and within him. Abraham’s Semitic ancestors from Akkad, who had conquered and assimilated Ur, had preserved the Sumerian originals as sacred works. (In the same manner, the works of ancient Greece were preserved by the later Romans, and although they were translated into Latin they were still venerated and read in their original Greek.) Now reading to himself in the palace library, the loss left Abraham dumbstruck: only these ancient tablets remained, small tombstones to the liveliness of the cosmic theater of Sumer.

In the absence of the living breath of the Sumerian theater, the gist of Abraham’s recognition of this can be grasped. It’s one thing to put on a play and another to create a theater that one lives with, day by day, as if in eternity. As we have seen, the makers would cease to know the god-statues they made and then watch them as others in the audience could, with a suspension of disbelief. This transition to becoming part of the audience required theatrical rituals of its own, as the sculptors in essence denied their knowledge of being creators of the statues. An imaginary cutting off of the maker’s hands was one of these rituals.

And it was not only participation in this theater that was becoming lost to Abraham in Harran, but also the questions about boundaries that the theatrical rituals dramatized: Is the work believable? Will the audience believe that this statue is something a god would want to inhabit? Although these statues have a life of their own, it’s not what the gods knew as life. All that humans can do with the social and psychological sciences, the Sumerians accomplished by creating a setting for the imagined forces of the gods, in which to watch and study. Yet one problem remains, and that is the problem of the stage. A stage requires our willing suspension of disbelief, and so immense attention was paid to the verisimilitude of the “life” of the gods. The Sumerians were a culture at play with this experience, able to hold illusion and disillusion in mind at the same time. This also supported the quality of their written works — and the necessity of an expansive imagination in the individual reader.

The great cosmic drama of Sumer revealed that a human being is not perfectly seamless clay like the statue, but has faults in it, holes in it, mortal holes. The holes of ingestion and excrement were obvious, likewise those of tears, sound, breath, and the hole of birth. But the biggest hole was unseen, the hole of death. The statues, which have none of these holes beneath their exquisitely painted surfaces, are not perfection but rather a means to connecting inner feelings with outer reality.

Yet the secret that the statues were not really alive did not require enforcement; everybody knew the secret of the solid core of wood and stone to the statues, in the same way that the priests and priestesses who spooned out the meal to the statues understood that it was theater and that they themselves were an important element of the theater when they ate the food that had been set before the gods. So how would this knowledge be transferred to a solitary reader, seated before a text written in clay?

Clay tablet

For one thing, the edges of the cuneiform letters could be physically felt, like miniature sculpture. Everything could be inscribed into the clay and held there, just as in the statues. One did not have to know it all, keep it in mind; and since nothing in the writing would be forgotten, the reader could imagine himself an observer of a literary theater. It was always there in the library, as it was in the cosmic theater of the temple. And thus the library was also a Sumerian invention.

But in Abraham’s circumstances in Harran, the time was already lost when a civilization’s imagination and sympathy were big enough to hold every dream, every thought, and put it all on stage, constantly before themselves, whether each person was a daily witness to it or not (if not, the votive statues would stand in for them). This was the human creation whose loss, felt by Abraham in Harran, may have driven him forward on his journey.

While living for many years in Harran, Abraham worked with his father in the donkey business, drawing up contracts, handling correspondence from as far as Egypt and Canaan. But he could still occasionally find himself at the palace library with permission to make a copy — of the Gilgamesh epic, for instance. For a trained scribe like Abraham, a tradition had long existed that allowed him to copy a classic for his personal library. For him it was now a private matter: to read to himself and remain in touch with the Sumerian civilizing spirit.

Abraham Reading to Himself

Enkidu made for Gilgamesh a House of the Dream God,

He fixed a door in its doorway to keep out the weather.

In the circle he had drawn he made him lie down

And falling flat like a net lay himself in the doorway.

Did a god not pass by? Why is my flesh

frozen numb?

My friend, I have had the first dream!

I have had this dream, Abraham said to himself, of encountering a god but not seeing it. The dream is like a stage shrunk to its essence, a theater of two, or of three. And I sit here as with two others: myself, copying, and the author who wrote. He has created this place for us, and it is also of what he writes: “Enkidu made for Gilgamesh a house.” It is a strange intimacy, what Enkidu has done, as the dream that Gilgamesh has is shared. In the same way, the author has shared with me a presence that neither of us has seen — but I have felt the same feeling of it as he, so long ago. It could only have happened in this place, in this dream house that I am copying, on these tablets.

The one born in the wild knew how to give counsel,

Enkidu spoke to his friend, gave his dream meaning:

My friend, your dream is a good omen,

The dream is precious and bodes us well.

So the dream is named, precious, but only as Enkidu has listened, the wild man who is at home anywhere in the world, and with the wildness of dreams.

My second dream surpasses the first.

In my dream, my friend, a mountain rumbled

And then threw me down, it held me by my feet.

The brightness grew more intense. A man appeared,

The comeliest in the land, his beauty astounding

From beneath the mountain he pulled me out and

He gave me water to drink and my heart grew calm.

On the ground he set my feet.

The mountain is like a god, it buried Gilgamesh, and to me it feels like the mountain of words I am reading. “A man appeared” — and that is me as I read and give life back to the text. But it is Enkidu, too, who interprets the dream of Gilgamesh:

Enkidu spoke to him, saying to Gilgamesh:

My friend, we shall overcome, he is different altogether.

Humbaba is not the mountain.

He is different altogether.

Come, cast aside your fear.

Enkidu tells his friend that Humbaba is not as frightful as a mountain, not to be so feared as a wild mountain. This, Enkidu the wild man, knows. He is here the wise man, King Gilgamesh the fearful child.

In this manner, the author of these tablets has turned me into his interpreter, I am the man alive with a mind still wild — yet he, the author, long since dead, he can live only by the breath of a comrade still alive, a friendly reader.

Locking horns like a bull you will batter him,

And force his head down with your strength.

The old man you saw is your powerful god,

The one who begot you, divine Lugalbanda.

His friend Enkidu reduces the mountain to Gilgamesh’s size, someone to lock horns with. And who is this mountain but the one who stands in for the father of Gilgamesh? This is what Enkidu interprets for his friend, who has failed to recognize how the creator god has turned into his personal god in the dream. But a wordless god in this dream — until Enkidu supplants the god with his own words.

And I had thought, from seeing the dramatizations in Ur, that Enkidu was no more than a wild man. As I read the tablets, now, I see that that he understands the drama of the gods in his wildness, as King Gilgamesh could not. It is as if the gods are wild too and the natural man in his wild element, Enkidu, is close to them. This makes the gods come closer to my mind, and I think how the fear of them and the love is mixed together, as with a father.

You loved the speckled allallu-bird

But struck him down and broke his wing:

Now he stands in the woods crying “My wing!”

It is easier to see the details now; I had not thought much of these words before. Why did Innana harm what she loved? It is because she is divided against the bird in the wild, her anger cares not. But what of the poet who writes these words? His love for the allallu-bird is stronger, for he interprets the song of the bird to mean — and to sound like — “My wing!”

In your presence I will pray to An, father of the gods,

May great counselor Enlil hear my prayer in your presence,

May my entreaty find favour with Ea!

I will fashion your statue in gold without limit.

Though he prays to the gods and promises statues of gold if they will spare Enkidu, King Gilgamesh would be ruining his intimacy with his friend by giving it a price. He disfigures the value of the statues of Sumer by reducing them to a matter of gold — he has turned spirit into gold. And it is gold I too pursue, the price of creating my own stage in life: I write contracts and not poetry. It makes me sad to read this.

May the high peaks of hills and mountains mourn you,

May the pastures lament like your mother!

May boxwood, cypress and cedar mourn you,

Through whose midst we crept in our fury!

May the bear mourn you, the hyena, the panther, the cheetah, the stag and the jackal,

The lion, the wild bull, the deer, the ibex, all the beasts of the wild!

May the sacred river Ulay mourn you,

Along whose banks we walked in our vigour!

May the pure Euphrates mourn you,

Whose water we poured in libation from skins!

What a grand list, a list like the lives of kings, these plants and animals of the wild, and the grass of pastures and the wild rivers. As if the gods are not necessary, as if the wild things form the great stage — here Gilgamesh invokes them like personal gods, intercessors to the high god. Gilgamesh speaks it. The poet writes it. Sumer enacts it: it creates the same place for these words as for the living things. A place where the loved comrade cannot be forgotten.

O my friend, wild ass on the run, donkey of the uplands, panther of the wild…

Now what is this sleep that has seized you?

You’ve become unconscious, you do not hear me!

But he, he lifted not his head.

He felt his heart, but it beat no longer.

He covered, like a bride, the face of his friend,

Like an eagle he circled around him.

Like a lioness deprived of her cubs,

He paced to and fro, this way and that.

It is no dream, this loss of a comrade — of a love as dear as a personal god. Like a personal god, the memory must be fixed for all time, an immortality, for what was life without it, or what could life be had he not lived? And here it is, before me, an immortality fashioned in clay, in this artful clay a mind may caress in the future.

At the very first glimmer of brightening dawn,

Gilgamesh sent forth a call to the land:

O Sculptor! Lapidary! Coppersmith! Goldsmith! Jeweller!

fashion my friend… !

Your eyebrows shall be of lapis lazuli, your chest of gold, your body shall be of…

I shall lay you out on a magnificent bed,

I shall lay you out on a bed of honour.

I shall place you on my left, on a seat of repose;

The rulers of the underworld will all kiss your feet.

The people of Uruk I shall have mourn and lament you,

The thriving people I shall fill full of woe for you.

After you are gone my hair will be matted in mourning,

Clad in the skin of a lion I shall wander the wild.

It is as if I am being called, the sculptor, to make the friend’s statue, and all the occupations of the temple are on display, the jeweler who fits the turquoise of the eye, the lapis lazuli of the eyebrow. But it cannot have a mouth opening ceremony, Enkidu is not a god, and the king knows this, his hair torn. “In the skin of a lion” he returns to the home of Enkidu, the wild — but it is only a skin, a costume.

And it is as if the poet has lost Sumer, lost the enlivening of the statues, and it is me — I, too, have lost the great drama! But King Gilgamesh tries to impress Enkidu everywhere, on Uruk and even on the underworld, this is the depth of impression that the loss of Enkidu has left.

Further, it is as if he is founding a new culture, a burst of creative arts dedicated to Enkidu, and yet I feel it is futile, it is all lost, Enkidu is dead and Gilgamesh knows it. And the poet? The poet who makes me weep for the loss of Sumer, the loss of the spirit of the poem, the author is as myself. It is lost, but it may be remade in words, in the voices that words evoke, in those who are still to be born, in the promise of a future.

For his friend Enkidu, Gilgamesh

Did bitterly weep as he wandered the wild;

I shall die, and shall I not then be as Enkidu?

Sorrow has entered my heart!

Gilgamesh “wandered the wild” but he has lost it, he cannot even see it, it is a civilized sorrow that allows him to see only his own death. Death shows that everyone will be lost, even Gilgamesh himself. That is why he finds a new attachment to Enkidu in death — “shall I not then be as Enkidu?” But it is an attachment frozen in time; it does not admit how it is inevitable in every affection that it lead to death and separation. Gilgamesh is a king, and so it was hard for him to believe in his own death. What comes after? He does not know yet, but the poet knows. It is the making of memory. But Gilgamesh does not know this yet, and must repeat himself until he can discover what to do.

My friend, whom I loved so dear,

Who with me went through every danger,

The doom of mortals overtook him

Six days I wept for him and seven nights.

I did not surrender his body for burial

Until a maggot dropped from his nostril.

Then I was afraid that I too would die,

I grew fearful of death, and so wander the wild.

What became of my friend was too much to bear,

So on a far path I wander the wild.

How can I keep silent? How can I stay quiet?

My friend, whom I loved, has turned to clay.

Shall I not be like him, and also lie down,

Never to rise again, through all eternity?

I heard in this now the Lamentation for Ur and for other cities. The city was destroyed, the road of Sumer had come to an end, and only the words remained. Something more than the words, too. The inspiration. The breathing of the words of Gilgamesh even after his death — this the poet knows. We give in to death, acknowledge that it belongs to the gods — no, to the whole creation, to the wild. At the same time we do not give in, we do not mistake the god for the statue, we hold on to the memory, although “what became of my friend was too much to bear.” In the very words, it is borne. If not by Gilgamesh, then by the poet. Each by ourselves bear it alone, reading the clay.

Said Gilgamesh to her, to the tavern-keeper:

Where is the road to Uta-napishti?

If it may be done, I will cross the ocean,

If it may not be done, I will wander the wild!

In place of the wild, it is a journey into the unknown that Gilgamesh finds, “I will cross the ocean.” To visit Uta-napishti, the flood survivor — who would think of that? Out of a lost and desperate way, a journey appears. So we are here, in Harran, and in place of the temple drama I have words and donkeys that travel the greatest distances.

Man is snapped off like a reed in a canebrake!

The comely young man, the pretty young woman —

All too soon in their prime Death abducts them!

No one at all sees Death,

No one at all sees the face of Death,

No one at all hears the voice of Death,

Death so savage, who hacks men down.

What a need is here to make of Death a presence, a statue with a face, a voice, an arm that hacks. The absence of the lost friend is complete disillusion: the comrades were not as one, though they felt it so. It could be true only in spirit, only for a time, and then in death they are separate as they were in life. Without the poet, the terror of death — that it cannot be affected, cannot be stopped — would be too much to bear. The poet has made of Death a presence.

Ur, too, was only for a time, but the poets of the Laments have kept the memory alive. The poet of Gilgamesh has kept all Sumer alive, beyond what powers King Gilgamesh had. As I read I feel the absence of it — of Ur — so keenly that it is present again.

It was only for a time, this is the hard thing, and then it is rendered invisible, even as it still stands. The Ur that is usurped by Hammurapi and Babylon is still visible, but the loss of Sumer becomes an invisible presence. It is only for a time that anything lives. The toy model chariot on its woven palm frond rope, joy of my childhood, made by my father, was only for a time. The rope was never repaired when it frayed; the clay wheels never refinished. And yet never discarded, always on the shelf it remained, even after it was no longer an object of play. Finally left behind when we set out for Canaan, it remains with me as a memory in Harran, an invisible thing.

Not a seed. The invisible might be seen as a seed that falls and replants itself through time. A future from a seed. Here man is a reed only, a mere toy; broken off, there seems no future, but the broken reed is also a writing implement for the poet.

Ever do we build our households,

Ever do we make our nests,

Ever do brothers divide their inheritance

Ever do feuds arise in the land.

Ever the river has risen and brought us the flood,

The mayfly floating on the water.

On the face of the sun its countenance gazes,

Then all of a sudden nothing is there!

The abducted and the dead, how alike is their lot!

But never was drawn the likeness of Death,

Never in the land did the dead greet a man.

Two faces meet, the sun and the mayfly. All other faces are summed up in these faces that we never look into, the sun’s and that of the mayfly. The faces around the hearth, the scribes drawing up the inheritance contracts, the sad faces of the burial — all are just as vulnerable to the flood, all the faces.

But here the poet has revealed what is most strange: the disappearance of the face of the mayfly, for there can be no likeness of what we have not known. How to remember what has not a face? The poet knows our dependence on it, on putting a face on everything to make it present. The face of the sun, the face of death — though “never was drawn the likeness of Death.” What can we know without facing the absence of a face, what is unknown? The poet gives me the face of the tablet to read.

Gilgamesh found a pool whose water was cool,

Down he went into it, to bathe in the water.

Of the plant’s fragrance a snake caught scent,

Came up in silence, and bore the plant off.

As it turned away it sloughed its skin.

Then Gilgamesh sat down and wept,

Down his cheeks the tears were coursing.

Here is a scene almost too hard to see, too close to death. It is the plant that holds the gift of immortality Gilgamesh has found at the end of his journey. It is his for only the shortest of time. In a moment, a natural thing, a water snake bears it away. The man loses the secret of immortality to the snake.

It is as if Gilgamesh does not want it, does not smell it as the snake does. The smell of the plant, the desire for it, the man does not possess. What does he lose? His dearest one, Enkidu, he has already lost. The knowledge he too must die — but is this a loss or a gain of knowledge? Something is left in Gilgamesh’s tears; the poet has left a clue. The old skin must be let go, just as the snake sloughed off its skin. In the feel and taste of salt tears on his lips, an old life is leaving.

The king, Gilgamesh, will return to his city and build a new kind of skin of great works and deeds, the doors to Uruk renowned through time, older than Ur. But it as nothing compared to the living man that the poet has captured.

His name lives on, simply a name, the fifth name of the kings of Uruk, included among the hundred kings on the Sumerian King-Lists until the First Dynasty of Babylon and Hammurapi today. It will be the same for Hammurapi, for all the monuments and copies he will commission, only a name on the list of kings. But it will be the next work that I copy for my private collection, the Sumerian King-Lists, a frame of history that holds the passage of time since before the Great Flood.

Men, as many are given names,

Their funerary statues have been fashioned since days of old,

And stationed in chapels in the temples of the gods:

How their names are pronounced will never be forgotten!

Temples have been destroyed, statues broken, but all can be rebuilt. So the temple in Ur, as here in Harran, can stand and the temple life go on, and it is still capable of being lost, the life in them growing stiller the more they are copied, without the poets and the craftsmen alive to Sumer. Here in these tablets I have the living Gilgamesh to weep with, but in Uruk today, already Hammurapi has destroyed the city.

For the life of a scribe in Ur, even today but perhaps not for long, everything has a name. Everything is listed. This is how we learned the words, how to write — from lists. The great Sumerian lists were inspired. A copy only says “Remember” — the spirit to actually remember disappears without the sharp pinch of knowing that Sumer was long ago. The Sumerian King-lists say: This existed, apart from me, and is gone. What does the new Babylonian copy say? We can copy and keep everything for all time, it says, as if there is no loss.

What is the future of Abraham’s copy, my own copy? A pinch of loss when I see the name of Gilgamesh again but the name of the poet is lost. For I have only the name of the scribe who copied it in Ur. He has set his seal, but not remembered the poet.

David Rosenberg

David Rosenberg’s Abraham: The First Historical Biography is due out in paperback in April 2007. His A Literary Bible: A Poet-Scholar’s Collected Biblical Translation, 1973–2007, with Notes On How The Bible Was Written, is to be published in 2008. His newest piece, “The Authentic Poet in the Late Twentieth Century: Berrigan, bpNichol, and Yasusada,” appears online in the current issue of www.Fascicle.com

Additional recent pieces were published in See What You Think: Critical Essays for the Next Avant-Garde (Spuyten Duyvil, 2003). Rosenberg once edited The Ant’s Forefoot from Toronto’s Coach House, where he published the first four of his twenty-odd volumes of poetry, translation and essays, including his bestseller collaboration with Harold Bloom, The Book of J (Grove, 1990). Among his essays that document the current state of poetry, one of the first, “Frank Lima,” is reprinted in his The Necessity of Poetry (Coach House, 1973) and can now be read online at:

www.chbooks.com/archives/online_books/necessity_of_poetry

He lives with his wife, the writer Rhonda Rosenberg, in Florida, near the border of Miami and the Everglades wilderness.