This piece is about 10 printed pages long.

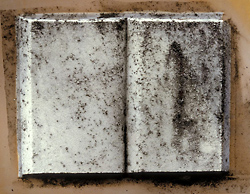

A facsimile of the Traherne book with a reproduction of a page of his handwriting.

1

The Original

In 1967, a passerby yanked a large, leather-bound book of neatly

handwritten pages from a burning rubbish heap in England. In 1982, it was

authoritatively attributed to that wondrously original 17th century

poet Thomas Traherne and identified as his last consuming project. Only

recently has it been restored enough to handle. Unpublished still, smelling

faintly of smoke and rot, part encyclopedia, part poetry, part visionary

exposition, it lies in its own tray in the British Museum not just like a

fossil, but very like Hallucinogenia, one of the strangest,

never-to-be-see-again creatures discovered in the Burgess Shale. The

manuscript’s curious formal structure is the template for the structure of

this essay about it. The full title for the work is:

paragraph 2

COMMENTARIES of Heaven

wherein

The Mysteries of

Felicitie

are opened

and

ALL THINGS

Discovered

to

be

Objects of Happiness.

EVRY BEING

Created &

Increated

being Alphabeticaly Represented

(as it will appear)

In

the Light

of

GLORY

Wherin also

For the Satisfaction of

Atheists, & the Consolation

of Christians, as well as the Assistance

& Encouragement

of Divines: the Transcendent Verities

of the Holy

Scriptures, and the

Highest Objects of the Christian Faith are

in a

Clear Mirror Exhibited to the Ey of Reason: in their Realitie and

Glory

3

Its Nature

What of this long-lost, multi-genre extravaganza can be translated across the centuries? More than I

imagined at first. In fact, if we to look closely at even one poem from

Commentaries of Heaven, we’ll find that Traherne’s

visionary imagination surprisingly anticipates contemporary phenomenological

philosophy, not releasing his work from its 17th century English and

Christian contexts, but preparing a curious place for itself in our own moment.

Which is to say: its implications still resonate.

4

Its Subject

What follows is an exemplary poem that appears between paragraphs

of prose in a section of the manuscript titled “Spiritual Absence,”

under the subheading “The Desolateness of Absence.”

5

That Man is Poor and Desolate whose Lov

None seeks, no man

sollicits, none Doth move,

Whose Brightest Splendors in the Dark do

lie

And all his Great affections are thrown by.

Rust covers his

Resplendent fancy, Dust

Soyls all his Powers, & his Lov doth

rust.

His Wit’s unseen, his Wisdom none admires,

His Souls

unsought, his favor none desires.

None vallues his esteem, his sacred

tears

No ey doth pitty, Fury no man fears.

His Passions are hung

o’er with Cobwebs, and

His greatest virtues idle in Him

stand.

His Courage no where is imployd his zeal

No Beauty doth to any

Ey reveal.

His Excellencies in a Silent Cave

Are hid; his very Body is

his grave.

His faculties are Empty, all his powers

Are Solitary,

Withered, Blasted Bowers.

His Wide & great capacity is laid

Aside,

his precept is by none Obeyd.

His very Worth’s neglected &

Despised,

His very Riches are themselves not prizd.

He is the

poor, forlorn and needy man,

That see, do, Prize, Enjoy, Admire at Nothing

can;

Whose Goodness cant itself comunicat,

Nor Avarice Enjoy

anothers State.

Whose Violent & Endless Lov’s

displeased,

Whose Great Ambition is by no man Easd.

Who no Dominion

hath, Whom no Mans Ey

Doth Prize, Exalt, Rejoyce in, Magnifie.

Who

reigns not always in anothers soul,

Whose Highness nothing can at all

Controul.

Who cannot pleas far more the Worlds! & be

A Bliss to

others like the Deitie.

6

THE DESOLATENESS OF ABSENCE

7

Its Distinction

As it is a religious poem, there is something odd here. For one thing, until the last line, there’s not a single reference to God. Instead, the poem focuses on man’s relationship to other men. More precisely, it zooms-in on the relationship of others to a spiritually desolate man.

8

Absence and Advent

By postponing until the ultimate line any mention of “the Deity,” the poem acts

out its desolation. The word God is missing from all sentences but the last

because God is missing from the subject’s soul.

9

The desolate

man is conscious only of a world of negatives elaborated in twenty two instances

of none, no, nothing, not, and the prefix un. His is a living

hell. All “His faculties are empty” and his “great capacity

is laid/ Aside”.

10

But the poem implies that even at the final

moment of his life, the man might alter his condition. The words

“bliss” and “Deity” in the ultimate line clarify

Traherne’s faith in the potential for redemption. Finally, in a wonderful

bouleversement, all those grammatical and lexical negatives serve to point

dramatically toward their opposites.

11

It is then, categorically, a

poem of Advent. God’s absence drains man’s being of its fullness;

without God, he cannot “be/ a bliss”. With the Advent of God,

Traherne suggests, man’s desolate consciousness will be transformed.

Weirdly enough, the initial experience of desolation may make salvation all the

sweeter, for as Traherne notes in the “Instructions” on Absence that

follow the poem, “The presence of God is more amiable to us, than it was

before the fall. For the consideration of his love in our restitution is an

infinite enjoyment: and perhaps truly greater than all the

former.”[1]

Photography by Denny Moers

12

Three centuries after Traherne writes “The Desolateness

of Absence,” the phenomenological philosopher Emmanuel Levinas writes

that it is “destitution...of absence that constitutes the proximity

of God”[2]. For Levinas, too,

absence prefigures advent, and “The negation that claims to deny being is

still, in its opposition,” involved with being. He iterates, with

crescendo: “Negation carries with it the dust of being that it

rejects.”[3] For Levinas, as

for Traherne, absence and negation presuppose presence and

signification.

13

Torn Awake by the Infinite

Traherne’s poem

describes a man asleep, his qualities all subtracted from their potentialities.

His affections are “thrown by”, cobwebs hang over his passions, his

virtues are idle and his splendors “in the dark do lie.” Only

God’s love can re-awaken what Traherne, in another poem, calls his

“infant-eye” so that he might contemplate

“infinity.”[4]

14

On a lovely parallel path that also links the infinite to the

“infant-eye” of newly awakened vision, Levinas suggests that the

idea of the Infinite―the Infinite in us―rouses a consciousness that

is not sufficiently awake.[5] He

explains, “Love is only possible through the idea of the Infinite, through

the Infinite placed in me by the ‘more’ that ravages and wakes up

the ‘less.’”[6]

Such proposals find ample affinities in Traherne’s “The Desolateness

of Absence” which specifically chronicles the ways in which a man is

less than what he might be were he awakened by the more of God.

15

Being

For Levinas, the thinking of human being and the thinking

of God’s being are complicated by the potential for God to signify a

“beyond of being, or

transcendence”.[7] This leads

him to reconsider the traditional opposition between ontology and faith and to

question whether “being is only a modality of

perception”.[8] Traherne,

equally concerned with God and with what it means to humanly be, gathers

together these core terms in his poem’s last lines. The final rhyme

between “be” and “Diety” not only brings the human and

Godly into relationship, resolving the poem’s negative skew, but it models

that relationship prosodically. The rhyme is, itself, the bliss of the human

tuned to the Diety tuned to the human.

16

Primary Consciousness and Merleau-Ponty

Traherne’s emphatically childlike outlook on

“EVRY BEING” in the extraordinary project of his Commentaries of

Heaven resonates and finds philosophical rapport in the theories not only of

Emmanuel Levinas, but of other 20th century

philosophers.

17

It takes just a small step to connect the Advent of

Christ to being, in Traherne’s terms, to “the advent of being to

consciousness”[9] which is how

Maurice Merleau-Ponty defines the concern of phenomenology. Both writers

advocate sweeping transformations of our normative modes of perceptual

awareness.

18

For Traherne, the Biblical injunction to “be born

again and become a little

child”[10] invigorates his

efforts to regain the “wonder” and “amazement” he felt

as a child, to cultivate childhood “bliss” into a mature state of

awe. Anyone who does so, he believes, will perceive the world to be a paradise,

since “Adam in Paradise had not more sweet and curious apprehensions of

the world, than I when I was a

child.”[11] Traherne advocates

an “original

simplicity,”[12] a condition

of awareness that might exist before linguistic and cultural influences

“Could breathe into me their infected

mind”.[13] Consequently, he

observes that “My very ignorance was

advantageous.”[14]

19

Maurice

Merleau-Ponty scarcely could have agreed more. He likewise blasted rational

thought for its tautologies, arguing that “Intellectualism and empiricism

do not give us any account of the human experience of the

world....”[15] Like Traherne,

he was obsessed with “attentiveness and

wonder,”[16] going so far as

to claim that the best formulation of the phenomenological

reduction[17] was articulated by

Husserl’s assistant “when he spoke of ‘wonder’ in the

face of the world.”[18] When

Merleau-Ponty makes his own case for a primary consciousness, he imagines

a state akin to Traherne’s “original simplicity”, a

pre-reflective awareness that reveals the “coexistence” or

“coincidence” of an embodied subject with the world. It is the

world, more specifically the body in the world, that structures perception,

Merleau-Ponty insists, and he quotes Cezanne’s boast that the landscape

thought itself inside him and that he was its

consciousness.[19] Traherne makes a

declaration just as bold and intuitive when he writes, “The world was more

in me than I in it.”[20]

Detail from Poetry Bridge by Diane Samuels

20

Flesh and Communion

For both

Traherne and Merleau-Ponty, the awakened consciousness makes evident a profound,

extensive interpenetration of all beings and things and a consequent breakdown

in the distinction between subjectivity and world. What Merleau-Ponty comes to

call “the flesh of the

world”,[21] Traherne has

already described as “An universe enclos’d in

skin.”[22] Playing on the

homonyms holy and wholly, Traherne avers “That all my mind

was wholly everywhere,/ Whate’er it saw, ‘twas ever wholly

there.”[23] A few hundred

years later, Merleau-Ponty initiates a kind of corollary assertion. He writes,

“existence can have no external or contingent attribute. It cannot be

anything―spatial, sexual, temporal―without being so in its entirety,

without taking up and carrying forward its ‘attributes’ and making

them into so many dimensions of its being, with the result that an analysis of

any one of them that is at all searching really touches upon subjectivity

itself”.[24]

21

For

Traherne, of course, primal vision, what he calls “primitive and innocent

clarity,”[25] reveals the

glory of God. Although Merleau-Ponty concludes that “the subjectivity

that we have run up against does not admit of being called

God,”[26] his own notably

poetic and sometimes overtly religious language―for instance, he speaks of

a communion of perception with the perceived and a primary faith

that binds us to the world―draws his work ever closer to Thomas

Traherne’s.

22

Intersubjectivity

Perhaps the most

remarkable characteristic of “The Desolateness of Absence” is its

focus on the social fabric. The subject’s desolation is measured

primarily in terms of his relations to other men and women. He is poor because

no one else seeks his love. No one values his wit, his wisdom, his tears, his

fury, his worth or riches. No one else’s eye prizes, exalts, rejoices in,

or magnifies him. His soul has been cut loose from the bonds that would connect

it to other human souls. Indeed, he has a subjectivity, but no

intersubjectivity. Unrelated, he stands apart.

23

Yet the

poem’s rhymed couplets insist upon relationship, the union of words. If

the man’s powers “Are solitary”, the poem’s power to

make pairs is not. Bandying sounds back and forth, the rhymes instantiate an

attunement, flashes of recognition and affiliation. Even the man’s

desolation is structured in terms of relationship. Each of his attributes is

matched with its eclipse. The wash of negatives all modify qualities that DO

exist. The man has a goodness (even if he can’t communicate it).

He has riches, worth, great ambition, and a wide and great capacity, even

if they’re frustrated or neglected. His defining characteristics are not

essential, but stand in relation to what they might otherwise be.

24

Both the interactive structure of the poem, its polarities

and rhymes, and the content, its descriptive failures of a man set apart

from others, would imply that identity must be relational, developing out of a

collaborative involvement with others, world, and God. In the parlance of

contemporary phenomenologists, such a position is intersubjective.

Traherne’s desolate man refuses to recognize the structure that binds him

to others and to the world itself. As a solitary individual, he is

impoverished, isolated from relationships that give rise to meaning, value, and

selfhood. He has become, finally, unrecognizable. If Traherne again seems to

have anticipated a phenomenological stance, the ongoing reciprocity called

intersubjectivity, he finds precedence in the Bible where Paul preaches

to the Romans that we are “members one of

another.”[27]

25

Paul

Ricoeur, whose philosophical thought also develops out of phenomenological

inquiry, elaborates upon that membership extensively. He notes that “the

world has no meaning before the constitution of a common

nature.”[28] It is the other,

he writes, who “helps me to gather myself together, strengthen myself, and

maintain myself in my

identity.”[29] In the prose

passage prior to “The Desolateness of Absence,” Traherne declares

that “A man is not desolate when his body is alone, but when his mind is

so too.” It is due to solipsism that the desolate man finds “his

powers/ Are solitary” and his “great

capacity is laid/ Aside”. Using words

very similar to Traherne’s, Ricoeur observes that “It is in

connection with the notions of capacity and realization―that

is, finally of power and act―that a place is made for

lack and, through the mediation of lack, for

others.”[30] Toward the end

of his investigations in Oneself as Another, Ricoeur draws a conclusion

that finds its ideological rhyme in Traherne’s poem. Otherness, he

recapitulates, is necessarily “enjoined in the structure of

selfhood.”[31] We find our

riches, in other words, when we learn to “be/ A bliss to

others....”

26

Intentionality

The great leap into

phenomenology comes (through Brentano) with Husserl’s insight that

consciousness is always conscious of something; it is object directed. Our

relationship with objects is not something inserted between consciousness and

the objects. That relationship is consciousness itself. Traherne, once again,

seems to have prepared the way. In a subsection from “Spiritual

Absence,” Traherne boldly assures his readers that “Spiritual

absence.... is an absence of our thoughts from any object

whatsoever.”[32] He develops

this idea further, claiming that “All objects are sacred treasures, freely

given us of God, who loving us infinitely, delighteth that we should be happy.

Willingly therefore to be absent from them, implieth the greatest guilt of which

nature is capable: ingratitude.... For nothing is more natural, than the union

of faculties, which God hath designed to be joined, to their

objects.”[33]

Traherne’s understanding extends, of course, from his assumption that God

is the constant and default object of man’s eye and that every worldly

object is revelatory, but his very intuition of intentionality uncannily

foreshadows the phenomenologists.

27

Time

Uncanny too are the

affinities between Traherne’s mystical and Merleau-Ponty’s

phenomenological senses of time. Merleau-Ponty is tapping Henri Bergson’s

thought, but Traherne is tapping his own ecstatic vein. The soul, Traherne

explains, “for being transcendent to time and place is measured by

neither.”[34] In another

section of Commentaries of Heaven, he asserts that all time exists in the

present. The soul, he writes, can experience every historical and Biblical

moment “as if all these were this moment in

acting.”[35] Merleau-Ponty

says virtually the same thing. “What is past or future for me is present

in the world,” he writes. And “Past and future exist only too

unmistakeably in the world, they exist in the

present.”[36] Is it

Merleau-Ponty or Traherne who declares “Objective presence is real

presence and the best

imaginable”[37]? That’s

Traherne. And which of them, do you suppose, writes, “Everything,

therefore, causes me to revert to the field of presence as the primary

experience in which time and its dimensions make their appearance unalloyed,

with no intervening distance and with absolute

self-evidence”[38]?

28

End Time

Here, where Traherne demolishes time and his work pops

out of its century just in time to be plucked from a burning heap of rubbish;

here where we find it has something to offer to a 21st century

philosophical dialogue; here in the clear mirror that he holds to the light of

glory, it’s time to consider how Traherne’s presence, knotted into

the lyric miracle of his writing, might be threaded to our own urgencies. Nor

has Traherne stopped writing his way beyond us and into a future that, though it

measures nothing, translates everything and so will no doubt find a place for

him.

Essay first published in Jubilat (United States)

[1] Thomas Traherne, in COMMENTARIES of Heaven, “Instructions” under subtitle “Absence” (British Museum).

[2] Emmanuel Levinas, On Thinking-of-the-Other: Entre Nous, trans. Michael Smith and Barbara Harshav (New York: Columbia University Press, 1998), 57.

[3] Emmanuel Levinas, Of God Who Comes to Mind, trans. Bettina Bergo, (Palo Altol, CA: Stanford University Press, 1998), 113.

[4] Thomas Traherne, “Sight,” in Selected Poems and Prose, ed. Alan Bradford (New York: Penguin Books, 1991), 132.

[5] Levinas, Of God Who Comes to Mind, 65

[6] Ibid., 67

[7] Ibid., 56

[8] Levinas, On Thinking-of-the-Other: Entre Nous, 68.

[9] Maurice Merleau-Ponty, The Phenomenology of Perception, trans. Colin Smith (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, Ltd., 1962), 61.

[10] Traherne, Selected Poems and Prose, “Centuries of Meditations 3.5,” 228.

[11] Traherne, “Third Century, I,” in Selected Poems and Prose, 226.

[12] Traherne, “Eden,” in Ibid., 7.

[13] Traherne, “Dumbness,” in Ibid., 21.

[14] Traherne, “Eden,” in Ibid., 7.

[15] Merleau-Ponty, The Phenomenology of Perception, 255.

[16] Ibid., xxi.

[17] Husserl’s premise is that it is necessary to bracket off the world in order to study its effects.

[18] Merleau-Ponty, The Phenomenology of Perception, xii.

[19] Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Sense and Nonsense, trans. Hubert L. Dreyfus and Patricia Allen Dreyfus (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1964), 17.

[20] Traherne, “Silence,” in Selected Poems and Prose, 25.

[21] Maurice Merleau-Ponty, The Visible and the Invisible, ed. Claude Lefort, trans. Alphonso Lingis (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1968), 146.

[22] Traherne, “Fullness,” in Selected Poems and Prose, 29.

[23] Traherne, “My Spirit,” in Ibid., 27.

[24] Merleau-Ponty, The Phenomenology of Perception, 410.

[25] Traherne, “Centuries 3.7,” in Selected Poems and Prose, 229.

[26] Merleau-Ponty, The Phenomenology of Perception, 410.

[27] King James Bible, Romans.

[28] Paul Ricoeur, Oneself as Another, trans. Kathleen Barney (Chicago: University of Chicago Press), 332.

[29] Ibid., 332.

[30] Ibid., 182.

[31] Ibid., 354.

[32] Traherne, “Its Nature” under heading “Spiritual Absence,” in COMMENTARIES of Heaven.

[33] Traherne, “The Evil of it” under heading “Spiritual Absence,” in Ibid.

[34] Traherne, “A Conviction” under heading “Spiritual Absence,” in Ibid.

[35] Traherne, “Its Objects in Particular” under heading “Agents,” in Ibid.

[36] Merleau-Ponty, The Phenomenology of Perception, 412.

[37] Traherne, “A Conviction” under heading “Spiritual Absence,” in COMMENTARIES of Heaven.

[38] Merelau-Ponty, The Phenomenology of Perception, 416.

Forrest Gander by Tad Richards

Forrest Gander’s recent books include Eye Against Eye (poems, New Directions) and A Faithful Existence: Reading, Memory, and Transcendence (essays, Shoemaker and Hoard). Among his translations are No Shelter: Selected Poems of Pura Lopez Colome, and (with Kent Johnson) two books of poetry by Jaime Saenz, most recently The Night (Princeton University Press, 2007). Gander’s translations of Coral Bracho’s selected poems, Firefly Under the Tongue, are forthcoming from New Directions in 2008.

More about this writer: the Jacket

Author Page offers links

to writing by or about this writer elsewhere in Jacket magazine.