Five poems:

The Sun Rises

The Saints

After Rodin’s The Muse (1896)

At The Library

Troupe

This piece is about 4 printed pages long.

It is copyright © Michael Harris: Five poems and Jacket magazine 2007.

The Sun Rises

Sour-breathed, too sleepy

for any appropriate touch,

they fondle each other awkwardly

too early in the morning, awakened at five

by the salt-air and light flowing in

through the broad motel windows

they were too drunk to shut the previous night.

Lie there, unsettled, ten yards from the sea’s

seemingly natural turns drawing curtain after curtain

on its own endless wash of applause, in artless rehearsal

that mimes the final play itself.

Above the motel, the sun rises steady as a spot

shining on the ocean’s virtuoso performance,

on all that’s effortless

and good at it.

The Saints

We have confined them to small rooms

and narrow beds. They have to live in silence, but with

mice breeding hourly in their walls. Though our furnaces

steam fullbore through the night, we keep

the rooms of the saints very cold.

For solace, they look through the cellar keyhole

at the lost souls roaring at the light

which plasters them helplessly to the ceiling.

Their beds are also much too short.

Their legs are numb to the ankles,

and cold to the knees: they hang bulbous

off the bed between severe iron railings,

paling in the cold like winter squash

hung over the parkinglot fence

in the last farmers’ market of the year.

For their despair, the saints endure hopelessly

thin electric heaters popping their vertebrae

on the long rack of winter. For comfort, they listen

to the ineffable voices of water ascending, then

descending screaming into the dark gargle of pipes.

When the cold’s at their thighs,

they no longer reproduce. Soon, they can’t eat.

Their hearts, like those of jilted lovers, begin by degrees

slowly to cool, as when the first flush of lava

enters finally the open body of the sea.

Their eyes take on the granite look

common to all the saints. Even the hair becomes numb.

But they are different than we are:

we thought they were dead, but they were sleeping,

only sleeping. When they wake, they tell us

what they saw in their fevers. We see mostly how

all their extremities wiggle, and return to pink.

After Rodin’s The Muse (1896)

He caught her just in time, falling–

as clearly she was–slowly asunder.

And quickly cast her several remaining parts

in a body he arrested in the process

of dispersal, so that half her knee is lost,

her arms fallen completely off; but her belly

and full trunk still manage the life

that life wants further to remove from her.

Even the stone seems to want her

to sink down into it, beyond whatever

miracle could stop it. So now he has her

pulled relentlessly down, left alone

to incline her solitary ear

to earth, to listen to whatever will prevent

the unthinkable from happening.

At The Library

I’d grabbed The Dictionary to look

something up and out popped

a grasshopper. A dead grasshopper,

perfectly preserved but for a slight

tilt of the head, such as one might exhibit oneself

if one were browsing through the Ms and came across

a smear of desiccated bug goo scumbling the page; and one

maverick eyeball pressed into the shape of an asterisk

right next to the word “manifest” — which, says The Dictionary,

means: plainly apparent to sight or understanding; to reveal;

to prove. Also: an itemized account of a ship’s cargo; the roster

of passengers for an airplane flight; a detailed list of

the cars of a train; and, last: a fast freight train.

The sum of such a list may indeed say something

about the development of human consciousness

historico-linguistically-speaking, as all of these definitions

derive directly from the one Latin word manifestus, meaning,

literally, “struck by the hand”, which is remarkably similar

to what appears to have happened to that grasshopper. Perhaps

he’d been stuck on some word on that page in the space between

“Mancunian”, that is, a native of Manchester, England, and

“maniple”, an ecclesiastical word meaning

a band worn on the left arm as a eucharistic vestment;

“Maniple” is also, of course, a non-ecclesiastical word

describing a subdivision of a Roman Legion containing either 60

or 120 men. Such a discrepancy of number would certainly have given

the grasshopper pause: and “Mancunian” defies all English logic, even if

its etymological provenance is the Medieval Latin,

that most sensible of tongues. True, his investigations

would scarcely have been in the league of inquiry

that deals with the Nature of Good and Evil, say; or whether

God is “that than which nothing greater can be thought.”

Neither would he have known that a bunch of Roman maniples

were once stationed in Mancunium; that Mancunium became

Manchester; and that Manchester was home to a cluster of priests

with armbands. Still, how to distinguish one maniple from another

would have taken that insect-brain well into the night. Sad to relate,

but when whatever Hand of Fate struck that starcrossed head,

that bug’d’ve found himself transported, teleologically-speaking,

a country mile beyond any ability to be inquisitive — or astonished,

or anything! The Librarian, turning the lights off and clearing the desks,

would have shut the book up, and squished it back up on its shelf —

unwittingly contributing evidentiary proof that “manifest”

was indeed that particular orthopteroid’s destiny,

closing in upon him as it did, like the fast freight train it is.

Troupe

Folded into its trucks,

the circus dreams of houses.

Wherever the road led,

there we took the animals

for a week in a farmer’s field.

Our hummingbird blur

at the mouth of the town.

Where the wind howled, there we pitched our tent.

Half-naked, the pony-girls shivering for the seamstress

in their slips of silk, the acrobats and roustabouts

losing their footing in a collapsed architecture of mud.

We light the lamps at nightfall

and creep through the streets of the town,

posting news of the circus: a broadsheet of the girls

borne on the gliding backs of horses

or held like trophies aloft by one foot.

All manner of beasts prowling

the imaginary jungle of the ring.

Down from the parish of their houses

to our temple of canvas and straw,

the villagers make their visit.

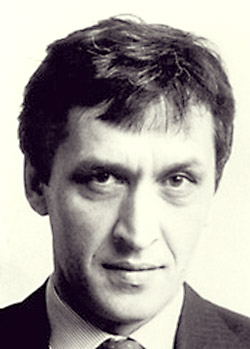

Michael Harris

Michael Harris was born in Glasgow, Scotland, in 1944. He has taught in the English and Creative Writing Departments of McGill and Concordia Universities, and at Dawson College in Montreal. For over twenty years he was Poetry Editor of the Signal Editions imprint of Véhicule Press in Montreal. His collections include In Transit (1985) and New and Selected Poems (1992).

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/34/c-harris.shtml