with a digression on his aleatory, kinetic and other off-the-page practices

This piece is about 21 printed pages long.

It is copyright © Laurie Duggan and Jacket magazine 2007.

Note: unless specified all page references are to There are words: Collected Poems, Exeter, Shearsman, 2006, 496pp.

paragraph 1

Gael Turnbull’s life took on a circular shape like some of his poems: he was born in Edinburgh in 1928 and returned there on retirement from medical practice in 1989. He grew up in Jarrow and Blackpool, migrating with his parents to Winnipeg at the beginning of the war and subsequently studying in both Britain and the United States. He became a GP and an anaesthetist, working in Ontario, London (UK), Ventura (California), Worcester and Barrow-in-Furness. His first work to appear in book form came out in Trio (1954) and his poems appeared in Cid Corman’s magazine Origin. In 1957 he started Migrant Press, a rare outlet at that time for British poetry of a more adventurous nature, as well as a place for American poets such as Edward Dorn. A first ‘selected poems’, A Trampoline, appeared with Cape Goliard in 1968, followed by Scantlings in 1970. Subsequent selections came out with Anvil (1980) and, in Canada (1992). Individual books had appeared over the years with presses such as Wild Hawthorn, Grosseteste, Pig Press, Five Seasons Press and Etruscan Books. In his later years in Edinburgh much of his work came out through local presses, like Hamish Whyte’s Mariscat.

2

There are words: Collected Poems is by no means a complete works. Turnbull’s oeuvre includes performance pieces, three-dimensional constructs and aleatory works [see BEPC and the images that accompany this essay]. Obviously it is impossible to reproduce work like this in conventional book form, though the purely verbal texts of some pieces are included here. For reasons of space the editors decided to keep Turnbull’s translations aside (a late example, Dividings, came out posthumously with Mariscat Press). These will no doubt be gathered eventually. Despite these omissions this impressive and carefully edited collection does make clear the breadth of Turnbull’s work and its uncommon bridging of perceived gaps between ‘avant’ and ‘popular’. It gives a good sense of the progression of Turnbull’s work, dividing it into the larger publications in which the poems first appeared, while using the latest version of each poem; not the easiest of tasks with a poet whose work often appeared in fugitive forms. Uncollected work is gathered in sections corresponding to the decade of its production (later uncollected pieces like some of the ‘Transmutations’ are clearly separated from published work under the same title). Apart from the preliminary draft of ‘from lazy blue flowers’ one other clearly unfinished piece has been included. This is ‘Sheddings’, the third section of ‘Transits: a Triptych’ [460]. It is printed with the marginal notes Turnbull would have probably removed (not an intrusive practice in this case).

3

Readers of Turnbull’s poems will be aware of his great formal resources. He is an inventor of forms as well as a writer who makes use of what’s to hand. Looking through There are words you notice a number of practises begun in the course of one collection and returned to and developed later. One of the earliest of these is the poem written in long lines that become small indented paragraphs, a practice used by both Whitman and Ginsberg (both indebted to the Old Testament), though here the effects are considerably different. Some examples appear in Bjarni, Spike-Helgi’s Son & other poems (1956), Turnbull’s third book, which consists largely of ‘free interpretations based on existing translations’ of portions of the Saga poems [482]. The use of old tales and histories had been a common practice since the Romantic era; their re-telling in contemporary language best exemplified in Ezra Pound’s reconstruction of Provence. Though not from the Saga sequence itself, ‘An Irish Monk on Lindesfarne, about 650 AD’ illustrates Turnbull’s skill as a tale-bearer:

4

On the road coming, five days travel, a Pict woman (big mouth and

small bones) gave me shelter, and laughed (part scorn, part pity) at

my journey. “What do you hope for, even if you get there, that you

couldn’t have had twice over in Ireland?”

Then I told her of the darkness amongst the barbarians, and of the

great light in the monasteries at home, and she replied, “Will they

thank you for that, you so young and naive, and why should you

go, you out of so many?”

I said that I heard a voice calling, and she said, “So men dream, are

unsatisfied, wear their legs out with walking, and you scarcely a

boy out of school.”

So she laughed, and I leaned my head on my hands, feeling the

thickness of dust on each palm . . .

[63-64]

5

A further example of this mode from the 1960s differs markedly from the work in Bjarni . . . Here the lines function as a painter’s notes, not as narrative. Opinion and description gain in immediacy through the very lack of explanation. The poem foregrounds Turner’s modernity; the feel of it is very much like Roy Fisher’s description of himself as a ‘1905 Russian modernist’ [Fisher, 1968].

6

A charge was inserted under the foundations and detonated . . .

The sun has disappeared leaving part of itself adherent to several

fragments of vapour. A gold sovereign comes in handy as

replacement.

The sky has been pried loose from the horizon. The blue has taken

the strain by splitting into radial fissures of indigo. Tack it together

somehow with rivets of carmine.

Then go home, have a glass of sherry, and look at it again.

Tomorrow we will begin the reconstruction of heaven. Meanwhile,

this evening, demolition has its attractions.

Accidents, too, can be very useful.

Not to forget the weather. A very proper subject for conversation.

The damp has penetrated more deeply than we might have

supposed. The light itself is warped. Even the clouds are affected

by mildew.

Our text for the occasion being: “. . . to preach deliverance to the

captives and the recovery of sight to the blind, to set at liberty

them that are bruised . . .”

The colours imprisoned in daylight.

[‘Thoughts on the One Hundred and Eighty-Third Birthday of J.M.W. Turner’, 165]

7

The voice in these poems is quite different to the knowing tone of Turnbull’s ‘mainstream’ British contemporaries. In these pieces the ‘sensibility’ presented is neither remote nor to be confused on all occasions with the writer’s own. Things are pared down and shaped as in a documentary, but not used as a kind of authorial alibi. Turnbull’s own take on the house style of the 1950s might be glimpsed in a poem like ‘Now that April’s here’:

8

It’s raining on the Brussels sprouts.

The fire is smoking in the grate.

Macmillan says he has no doubts.

Will Oxford beat the Cambridge eight?

Some bright intervals tomorrow.

Sixpence on a football pool.

Seven percent if you want to borrow.

Charles is settling down at school.

Put the Great back in Great Britain.

Write a letter to The Times.

Lots of fun with Billy Butlin.

It’s a poem if it rhymes.

[88]

9

From the beginning of this volume, and through its formal adventures, certain forms of address persist: the aphorism, the moral tale, paradoxes of the ordinary, though none of these end up being like what you’d get in Larkin. Here are two further examples:

10

Daily they toiled across the dunes of snow,

Northward and northward on that twilit sea,

Knowing before they started that their goal

Was but the day of their own turning back . . .

. . . . .

But they did not know that, as they marched

So strictly north, beneath the ice

The ocean moved them southward, just as fast —

And measured by the stars they had not moved at all.

[‘Nansen and Johansen’, 29]

#

11

Remake the world?

Remake myself?

Troubles enough

rewriting this.

[‘Remake’, 263]

12

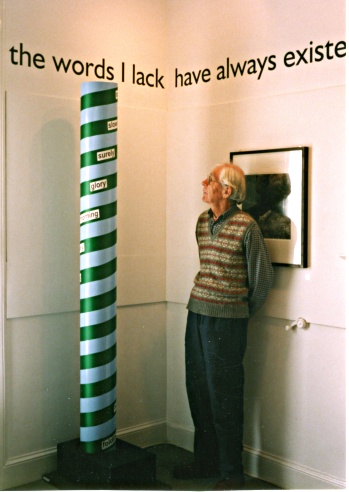

Gael Turnbull with »Morning Glory». Photo by Jill Turnbull.

The modes Turnbull makes use of are both old and new and not necessarily those one would expect of a card-carrying modernist. There are a significant number of works that make use of simple ballad forms alongside the less conventional structures. The forms, in all cases, match their perceived purpose. William Carlos Williams’ prohibition of the sonnet holds good (I can’t find any examples in the book), but Turnbull did try on the villanelle [see ‘You Said I Should’, 71]. This might seem anomalous until we realise that the use of recurring lines might lend itself to the sensibility of someone who would later develop forms of his own that used the devices of repetition, intertwining and circularity.

13

In some poems there is a sensibility shared with that other ‘struggler in the wilderness’ of postwar British poetry, Roy Fisher. In an autobiographical piece, Fisher mused on the early 1950s and on his first contact with Turnbull. Gael had been commissioned to make a selection of new British poetry for Cid Corman’s Origin, had seen a poem of Fisher’s in a little magazine and had written to him. Fisher soon found himself introduced to the work of Williams, Bunting, Duncan, Ginsberg, Zukofsky, Creeley, Levertov and Eigner among others [Fisher, 2000, 31-32].

14

An example from Turnbull:

15

They are digging up the street

Where I used to walk

Going for the milk.

They have put up a sign

Warning me to stop

Lest I fall into a pit.

The familiar surface

Of geometric concrete

Has given up its secret . . .

I had not thought,

Going for the bread,

That the daily journey hid

Such a mountain-depth of darkness . . .

[‘Excavation’, 40]

16

And from Fisher:

17

Down Wheeler Street, the lamps

already gone, the windows have

lake stretches of silver

gashed out of tea green shadows,

the after-images of brickwork.

A conscience

builds, late, on the ridge. A realism

tries to record, before they’re gone,

what silver filth these drains have run.

[‘For Realism’, Fisher 2005, 220-221]

18

Both of these poets began more or less in the dark, though Turnbull’s peripatetic existence exposed him at an earlier date to the currents in post-war American poetry. He had come across a magazine called Artisan, edited by Robert Cooper, which included work by Creeley, Duncan, Blackburn, Levertov, Olson and Corman, noting in a journal circa 1953 or 54: ‘Creeley comes very close to having done what I would like to do — one is always conscious of the living man, in activity, in common-place situations — yet the result is never commonplace’ [Turnbull, 1982, 10-11]. He had by then reflected on the work of Pound and Williams, the latter’s example particularly evident in his second book The Knot in the Wood (1955). There is a paring down here, notably in the poem (‘Thanks’) that gives the book its title:

19

Thanks and praise for

the knot in the wood

across the grain

making the carpenter curse

where a branch sprang out

carrying sap to each leaf.

[43]

20

From a relatively early date Turnbull was also making use of forms that would ultimately desert the conventional book page. His use of the column in some of these pieces carries an awareness of the shifts in concentration, the synapses, that permeate our consciousness. This concern would lead him into various formal ruses as well as those ‘words set free’ evidenced in Coelacanth and other multi-dimensional works. An early instance of the columns is ‘Homage à Cythera’:

21

|

How |

|

[183]

22

These columnular works often do more than hint at circularity in that the way words fall out might gradually work its way around to the beginning of a sequence. The phrases or qualifying words might partner themselves differently, the whole coming to seem like a dance in which you eventually meet the one you accompanied to start with. Later pieces in this book such as ‘Edge of air’ and ‘It is there’, both from the 1983 collection A Gathering of Poems continue this mode [257 & 259]. As does this one further example:

23

for us

a brightness

impelled to be uttered

for us

a season

sea-mark sheer

for us

a memory

so they can’t take away

for us

a love

though gripped, set free

for us

a voice

while breath persist

for us

an hour

retrieved from shambles

for us

a joy

to be lifted up

for us

a dream

where no word was

for us

a sleep

and not by thought

for us

a day

brimmed and to spare

for us

a gift

against mere limitation . . .

[‘For us’, 201]

24

This approach to poetry could also be said to revive one of its early usages: as charm and riddle. Turnbull’s work often makes use of ‘games’, though games, as we know, can be deadly serious matters. Even when the premises might suggest it, his aleatory works are never allowed to harden into exercises. ‘Twenty Words, Twenty Days’ from the book of the same name (1966) takes as its mode of operation words chosen randomly each day from the dictionary. These words, capitalised, may appear anywhere in the poem other than as first or last word. They vary from common terms to technical ones. In order of appearance they are: BOOMERANG, SLATTERN, DRAWSTRING, MORULA, INDIVISIBLE, UNDERVALUATION, APPARITION, VALENCY, GARGOYLES, VILLAGE, IRREVERSIBLE, MAIEUTIC, CARCASS, NINCOMPOOP, INTELLECTUALISM, PRECONCERTED, DEMULCENT, LATTICE, FAMILIARITY and POOR. The resulting poem is work of a high order as this section shows:

25

“I’m sure I can find

a thing of some kind,

a good kind of thing

to do with my string”

the forward path of the poet into the labyrinth —

not a poet, be it

noted, but the poet, that flourish —

but Theseus used his to find his

way back —

an INTELLECTUALISM —

as a prism to spread the light

for its parts (but looked through one sees only a jumble) —

a great

fankle, sometimes, to be unravelled —

or a spider, hanging its web for

what might be snared, arrogant in patience, and sticky —

or a child,

collecting bits of twine, knotting them end to end —

(how big will it

get)?

“with a big ball of string

I could do anything!”

[XV, 147]

26

Within the space of this section Turnbull makes use of a fragment of popular children’s verse, a myth, items of daily life, a slice of the theory of perception, and an unusual word: ‘fankle’ — a Scots term of Gaelic origin meaning ‘to tangle’. ‘Fang’ meant ‘sheepfold’, so the word relates to ‘fangle’ as well (looking it up in an online Scots dictionary [rampantscotland] I noticed another page advertising ‘Fankle wools and needlecraft’, a shop in Ayrshire).

27

Although he did not ignore the lyric Turnbull chose often to work in very short and in extended forms. In Briefly (1967) there is an early example of a form he invented, a two line poem with a larger than usual space between the lines:

28

The ever-presence

of your absence.

[‘The ever-presence’, 155]

29

He later called poems using this device ‘Spaces’, and noted of these ‘The visual “space” is, of course, merely a typographical indicator of what is more strictly a pause or hesitation, even a temporary dislocation of attention’ [483]. Here are some later examples:

30

They wanted for what they wanted

and were got by what they got

[‘A Marriage’, 310]

#

31

If I know you

tell me who I am.

[‘Beginnings’, 306]

#

32

The merely unspoken

now beyond utterance

[‘A Last Poem’, 313]

33

Within the space of each ‘pause or hesitation’ change occurs as a kind of synaptic leap. What was to be said, or what is to be said is said in exchange for something not said. These poems have a permanence about them that belies their fragility. Some of them even approach that supposed impossibility: the tautology that contains knowledge.

«A Perception of Ferns». Photo by Jill Turnbull.

34

Turnbull’s poems often contain or address argument, presuming two or more voices (or perhaps two aspects of the same ‘voice’), resulting in a form that could be characterised as antiphonic, a mode like a church ‘call and response’ in which each voice or half is of equal strength. As an example of work where the ‘voices’ are aspects of the one voice and statement is followed by modification or expansion is this piece from To You I Write (1963):

35

I would speak of him who could not speak —

in that soft distance full of milky light where residues of long since

flamed and sunken coal now float as minute fluffs of carbon in a depth

of air —

who could not speak of what concerned him most —

curdled by fumes from the barred chimney stacks of chemical works

that rise like masts above the seal-skin slates of droplet burdened roofs —

who was concerned instead with his allotment —

out of the fog that crawls upon the ochre bricks of caterpillar housing

rows and spreads like grease upon the iron furrows of a railway yard —

his piece of ground he worked, a garden there —

and in the alleys where the children’s footsteps sound like kettle-

drums whose beat is lost into the cracks between the paving

stones —

who was proud of his garden and spoke of it.

[‘I would speak of him’, 114]

36

The antiphonal poems would develop into another characteristic form in Turnbull’s later work, notably in the two long poems ‘Residues’, in the book of the same name (1976), and ‘Impellings’ (known in an earlier form as ‘As from a fleece . . .’) in For Whose Delight (1996) where the many voices of unnamed individuals or the multiple ‘voices’ of one individual intertwine in the text.

37

In an earlier prose piece ‘A Case’ [171], Turnbull had made use of a ‘moment’ of memoir, the observation of a patient under anaesthetic. ‘Seven snapshots, Northern Ontario’ [195] accumulates several of these ‘moments’ in fragmentary form. In ‘Residues: Down the Sluice of Time’ [222] and ‘Residues: Thronging The Heart’ [242], the fragments shift from gestures toward the randomness of the everyday to the sense of a shapely universe. Turnbull notes of these poems that the word ‘residues’

38

[is] to be understood in the sense both of ‘the left overs’ and ‘what survives’. ‘Down the sluice of time’: no overall formal verbal structure. ‘Thronging the heart’: though the effect may be subliminal, constructed on a system of pairs of words or phrases, recurring at alternating intervals of 3 and 5, back and forth between each ‘side’ or ‘strand’ and the other, and linking back on itself in a continuous band.

[483]

39

In the first of these poems (and in the later ‘Impellings’) the formal example of Basil Bunting’s ‘Briggflatts’ as well as its theme (memory, here in particular the memory of a youthful sexual encounter) is close to the surface:

40

glitter of what’s far off,

flash of the unseen

casting back the light

pulse of the stars — and the dark

consumes our sight — in a shuttered room

a candle flickers — and her eyes ignite

to rekindle

at source

the first fire —

need, need

against need,

the need fire —

to consume

with a need,

to blaze forth —

to ignite

the last void,

to flare silent

and a girl walks away down the street — her

hair hangs in a braid down her back — as

she walks, she moves, that braid moves,

my heart moves — desire moving, shaking

the heart

by the heart, taken . . .

[222]

41

These epiphanies are balanced by passages that reflect a longer duration as the warp of history shuttles through the woof of the text:

42

and once when a child, I saw in the British

Museum, a man from three thousand years ago,

preserved largely by accident and the drying

action of the sand, lying on his side in a

slightly huddled position, in exactly that

position in which I sleep myself

[223]

43

The poem weaves together childhood memoir, sexual history, episodes of medical practice, the matter of Scotland, Norse tales, John Bunyan, Mayakovsky and other characters and events. The shorter ‘Thronging The Heart’, is less digressive, knit perhaps with tighter thread, the counterpoint closer to the surface:

44

wrapt in a void

where we are bourne by chance of tide,

to make our home, who have

none other

stumbling to rest,

not needing further

while doing something else perhaps,

breaking kindling, buying bread,

tying a shoelace even, realizing

thrust of what must

with a great pain flooding over

us at the sight of so much beauty,

that country called Arcadia, where

we’d stumbled

helplessly thronged

to need each other

with gaps in the haze, in the

dawnlight glimpsed, one sight

plume of the breakers,

shoreward

thronging the heart

[244-245]

45

Part of the power of these poems, of ‘Impellings’ too, comes from the narrow path they take between exhilaration and despair. The contemplation of time carries within it an awareness of death, yet we can also become immured in ‘the comfortable / onrush of the universe’ at times broken only by the comic interlude or interruption that returns us to ourselves, our senses. This might be provided by possibly innocent commentators, like the poet-interjector at the reading with his ‘Speak up. Can’t make out / a word you’re saying’ [‘In Memorium Norman MacCaig’, 388].

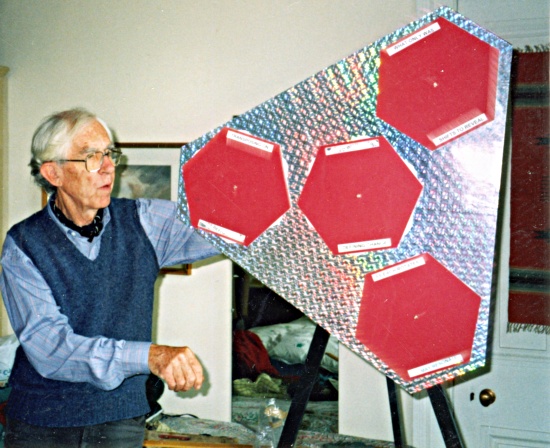

Gael Turnbull and the Kalexatron. Photo by Jill Turnbull.

46

‘Impellings’ is one of the great long poems of the twentieth century. It is structured more formally than the ‘Residues’ poems. Pairs of nine-line stanzas are separated by italicised phrases that connect as a long multivalent sentence themselves (‘As from a fleece, twisting together // according to the interval, according to the context // take hold anywhere and all shall follow // one gulp of air is all we have // impelled by riches, not poverty // articulate beyond mere sequence // in frequencies beyond prediction // granting momentum to each particular . . .’). These phrases act as an indirect commentary on the contained texts, weaving them together in their disparity.

47

The epiphany at the beginning of ‘Impellings’ has a Wordsworthian ring to it:

48

where imperatives of wind disperse

the fall of leaves — and more

than half a century of rings are since

inscribed within those trees that shroud

stone lions sentinel above a roar

of cars — only grass renews unchanged

amid the litter by the railed off sundial

‘silken as a dove’s wing, time’

where first steps lifted forward

near that remembered haven, walled

and sunlit garden of my grandparents,

a sea mark shrouded far astern until,

at random past that door, found open,

with young couple and their infant son

just moving in, had sight again

down passage to that same unchanged

held place, made present and thus shed

to him and those unknown, come after me

[366]

49

Childhood and youth when memorized turn themselves into something akin to legend. Past events grow luminous and shed their light on the present:

50

and dust, soon harvest, hum of a car,

long roads through Périgord to Ribérac

where as a boy I had always longed to go,

then to laze in the square, amazed,

drinking a ‘citron’, scent and savour,

to be where he was born who made his songs

in an older tongue less spoken now,

transmuted yet by others, lingering

on other tongues, paced syllables

[368]

#

51

and by the shore of an open bay

watching the crests of the long rollers

from the full reach of the Atlantic

as they move in from over the horizon

in unwearied sequence to some rhythm

familiar beyond definition, to remember

the eyes of a man by the road somewhere

in the southern bush who said, when asked

how many years he’d lived, just ‘much’

[375]

52

The question of memory as identity comes up when the poem addresses one, who

53

. . . marvelled at this propensity

to suppose ourselves possessed of distinct

and uninterrupted existence throughout

the course of our lives where memory

alone acquaints us with the continuance

of the succession of our perceptions

and is the source of this notion

of personal identity which it does not

so much produce as discover to us

and confessed that he allowed others

might be different in this particular

of their being but for his part, when

he entered intimately into what is called

himself, always stumbled upon some perception,

never caught himself without a perception,

never could observe anything but

each perception and were all removed

should have been entirely annihilated

[377-378]

54

‘Impellings’ is dense with association though it is not necessary for the reader to know all the persons and events alluded to. The poem carries its own sense of time, of things repeated and things unrepeatable, through its immediacy:

55

by shipyards and that venerable well

where history was compiled and I

first walked to school then later came

to stay with friends, midwinter festival,

by chance and choice, to call on one

whose resonance of words I knew,

thought dead or exiled, telling there

of his oldest friend, I never met, whose son

in time I did, to become thus mine

in the south where — at summer gathering

by resting place of one who shaped

from another tongue, fresh cadences — I met

the mother of that son, exiled, estranged,

from a former age who wrote of hills

where by vagrancies of time I came to walk

by another also venerated well

‘found cold spring water . . . bathed my eyes . . .

had quite forgotten how far one might see’

[366-367]

56

It would be a mistake to read the poem as a completely decipherable codex: nonetheless it is underpinned by the specificity of its references. In this particular passage I haven’t unpicked all the clues but I can detect allusions to Jarrow, where Turnbull did go to school and where the well associated with the Venerable Bede is situated; to Throckley up the Tyne valley from Newcastle and Basil Bunting (the one thought dead or in exile) whom Turnbull visited in the winter of 1956; to Bunting’s ‘oldest friend’ Ezra Pound, Pound’s son Omar, and Omar’s mother, Dorothy (Shakespear) Pound; and to the hills ‘where by vagrancies of time I came to walk’, which are most likely those of Provence (alluded to again later in the poem). Turnbull could have signposted all of this as I have done here, but unpacked references would have slowed the poem down.

57

Late in his life Turnbull continued to work in a variety of forms. The ‘Uncollected Texturalist Poems’ edit down various existing documents from the relatively ‘literary’ (Swift’s ‘Journal to Stella’) to the scientific (an article in The Geographical Journal from 1927) in much the same way as Charles Reznikoff fashioned his book Testimony: the grammar and vocabulary of the original prose texts are largely retained while the mustiness and repetition and those asides that dilute the effect of the whole are removed, the remaining passages broken into lines suggested by their own internal rhythms. ‘Though I Have Met with Hardship’ is adapted from an 1852 ‘letter from New South Wales’:

58

“This is a most beautiful country, all green

to the very tops of the hills, where we arrived

after a good passage but not a quick one.

98 days sailing and then three weeks in quarantine.

Seven persons died on the voyage, two with consumption,

and about 40 of the children, including

I am sorry to relate to you, our youngest lassie, Janet.

Though we had plenty of water and good victuals,

there were too many aboard, 950 emigrants as well as 60 crew,

and a great number took the ship fever . . .

[453]

59

The three groups of poems known as ‘Transmutations’ (from 1997, 2000 and uncollected) share some tactics with Roy Fisher’s ‘Metamorphoses’ [Fisher 2005, 316-318] though they also work like extended versions of the ‘Spaces’ poems. These prose pieces generally divide into two ‘paragraphs’ mostly midway though a sentence. They catch within themselves the frozen moment when something is realised or a paradox becomes apparent. They are miniature scenarios highlighting an element of storytelling that is never far from the surface in Turnbull’s work. The first example is as vertiginous as a parable by Kafka or Calvino, the second could be the breakdown for the mise en scène of a Hitchcock movie:

60

WHILE LOOKING for some missing papers, he comes across the remains of a small notebook. It appears to be the start of a sort of journal but undated and undoubtedly in his handwriting although he cannot recall writing it. He starts to read: “While looking for some missing papers . . . ‘and so on, down to’ . . . although I cannot recall writing it. When I turned the page . . .”

but at that point the writing comes to the bottom of the sheet and he feels his hand begin to tremble as he cannot bring himself to turn that page.

[407]

#

61

A MAN WAKES and hears his wife moving back and forth in the next room. Getting up to join her, he is distracted by the flapping of the curtain by the open window and glances out into the street.

Thanks to the darkness outside and the light in the next room, he sees the outline of her figure reflected in a window opposite. He stares, unable to tear himself from that image, as if it was finally able to clarify what had always made an illusion of their nearness.

[414]

62

I have dealt indirectly with translation considering only one poem in Bjarni, Spike-Helgi’s Son & other poems and some passages within the longer pieces, but I want now, if briefly, to address the work that moves away from the conventionally linear book-text and in some cases off the page altogether. Firstly it should be noted that for Turnbull there were no sharp distinctions between practices. His printed work itself often appeared in pamphlet form printed at home for various friends. As From a Fleece (an earlier version of ‘Impellings’) first appeared in 1990 as a long folded publication where the poem is paralleled by John Christie’s screenprint, much in the manner of Blaise Cendrars’ collaboration with Sonia Delaunay, ‘Prose du Transsibérien’ (a portion of Christie’s work appears on the cover of There are words [see illustration at top of page]).The variable sequence poem Coelacanth consists of a set of hand-lettered loose cards in a plastic envelope. One bordered card contains the initial words ‘That coelacanth / for which we fish’, the others consist of qualifying phrases that may randomly connect with it and each other, such as ‘breaking the surface / of what seems’, ‘as emblem of / both quest / and pilgrimage’, ‘with fins on stumps / or almost legs’ [Turnbull, 1986].

Portals. Photo by Jill Turnbull.

63

Other work of a kinetic nature includes ‘A drift of words’, an object designed to be hung as a word mobile; ‘Portals’, consisting of folding screens with slots to mask and reveal words; ‘Kalexatron’, a set of revolving hexagons attached to the axle of a bicycle wheel upon which words recombine; and ‘Morning glory’ (otherwise known as ‘the dancing drainpipe’), a green ribbon of text wrapped around a pipe that rotates like a barber’s pole [the last four items are illustrated].

64

Traces of ‘kinetic’ and other visual work are not entirely absent from this collection. Some pieces are presented in There are words as purely verbal texts, such as ‘from lazy blue flowers’ [459]. This draft of a commissioned piece (incidentally Turnbull’s last poem) was intended as a site-specific work whose lines were to radiate outward across a floor from a flax seed, the whole to be visible from a circular staircase. ‘For André Breton One Hundred Years from his Birth (1896-1996)’ is the text from a three-dimensional work, ‘The Breton Box’. This piece includes phrases adapted from the Surrealist Manifesto:

65

“Je cherche l’or du temps”

that the working of the mind might not just understand itself but in the real expression reveal its workings surely though how can we if only in dreams even derangement when to explain a joke without erasing is impossible and if the most potent is the most fleeting and the most naked is the most powerful where the embrace of poetry like love so long as it last is proof against all evasion upon the misery of the world if all this and the disordered sheets for it happens as in a bed the polarity to engender and if they tell me what’s inscribed on your grave who was never that where else to find words for the gold of each moment where there’s always the marvel of a shovel to the wind in the sands of the dream and always an arrow let loose as a star in the pelt of the night that the working of the mind

[435]

66

Some of Turnbull’s three-dimensional works were shown recently at the British Library in London in an exhibition centred on the productions of Migrant Press. Many of them, along with other kinetic pieces, are to be gathered together in the collection at St Andrews University. Other site-specific works such as ‘A Perception of Ferns’ which had been installed at the Kibble Palace, Glasgow Botanic Gardens are, for the moment, available only in photographic record. That particular piece consists of a sequence of cards with words printed mirror-wise and upside down arranged around the fish pond so that the reflections read as positives. The cards encircle the pond, rejoining at the ‘beginning’ [see illustration]. A slightly different wording appears in the text printed in There are words, the on-the-page version making use of columns:

67

|

from unseen source |

what’s now revealed |

[439]

68

Some of Turnbull’s kinetic works were used in performance pieces at the Edinburgh Festivals and other events. With busking, the work shades into the purely ephemeral, but, by all accounts, Gael thoroughly enjoyed these activities. He was a founder member of the Faithful City Morris dancers in Worcester and subsequently joined ‘sides’ in Stratford and Ulverston, composing and performing poems especially for the dancers. Some of these, such as ‘There’s more’, addressed to the Faithful City Morris Men, [247], survive to appear in There are words. Many others may only have appeared on cards typed for the occasion. The author noted,

69

I have often had the wish that I might have been born into another age and had the fortune to be court poet, maker or skald, to a minor chief or lord, called upon to provide poems for particular occasions, to celebrate, to mourn, even to castigate or to jest, finding voice for public and private experience, in a context which could be defined.

[479]

70

Perhaps poetry as a whole could be considered as a form of silent ‘busking’ with an audience response at times difficult to discern. Turnbull suggests as much in the title poem of his book For Whose Delight [353]:

71

For whose delight

do we perform these feats

under the spangled big-top

of the turning sphere,

thronging the arena

with our dreams and needs,

jumping through flaming hoops,

striding on wires across the air,

spurred by a cracking whip, a sugar lump,

of fear, desire

when we hear no cheers

or laughter from out there

in the banked darkness

where the audience should be?

BEPC (British Electronic Poetry Centre) biographical entry:

www.soton.ac.uk/~bepc/index.htm

Cendrars, Blaise, Complete poems, translated by Rod Padgett, Berkeley, University of California, 1992.

Fisher, Roy, ‘Antebiography’, in Interviews Through Time and Selected Prose, Exeter, Shearsman, 2000, pp9-33.

Fisher, Roy, The Ghost of a Paper Bag: Collected Poems 1968, Fulcrum, 1968.

Fisher, Roy, The Long and the Short of It: Poems 1955-2005, Highgreen, Bloodaxe, 2005.

rampantscotland, http://www.rampantscotland.com/parliamo/blparliamo_verbs.htm

Turnbull, Gael, ‘Charlotte Chapel, the Pittsburgh Draft Board and Some Americans’, PN Review, 28, 1982, pp9-11.

Turnbull, Gael, Coelacanth: a variable sequence poem, Edinburgh, 1986.

Turnbull, Gael, Dividings, Glasgow, Mariscat, 2004.

Turnbull, Gael, There are words: Collected Poems, Exeter, Shearsman, 2006.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/34/duggan-turnbull.shtml