JACKET INTERVIEW

Bob Arnold

in conversation with

Gerald Hausman

Vermont / Florida, 2007

This piece is about 12 printed pages long. It is copyright © Bob Arnold and Gerald Hausman and Jacket magazine 2007.

Gerald Hausman, left, with Bob Arnold. Photo Hannah Greaux.

Bob Arnold is one of a kind. There is no one quite like him in recent American poetry, and by that I mean poetry being written in the last four decades, during which time I have come to know Bob and his work in a kind of intimate way. I wrote the first overview of Bob’s poetry in the early 80s for The Bloomsbury Review. But that aside, I’ve been an admirer of the way he and his wife Susan have lived: reclusively, naturally, poetically, and I might add, a bit stoically. Bob’s built a very lovely permanent retreat in the woods of Vermont and there he has written finely crafted books for so long that I have come to expect them like the falling golden and red leaves of his October homeland. Having just come from there, having followed the river under the shadow of the mountain, and noting the white-steepled church where Bob and Susan were married in the 70s, and the red covered bridge through which you enter the nadir of Bob Arnold’s dreamworld, a world that is as real, as sap-filled and stone beautiful as any poem he’s written, and come out into the sunshine of his little ledge surrounded by a veritable village of gnome cottages, all built by Bob and his son, or Bob alone, and the little houses standing in the blue glare like poems. Two of these outbuildings are full of books, handpresses, mementoes of many kinds, but all speak of years come and gone, poems built and shaped by hand, stone laid longitudinally straight and correct, spaces between thin as a breath. The stone scribe is at home, standing in the sun with his beautiful wife. Go get his books. Read them. You’ll be better for it.

— Gerald Hausman

paragraph 1

Gerard Hausman: 1. As a kid growing up in the northwest Berkshires of Massachusetts you saw a lot of timber coming and going at your father’s lumber business. How did this affect you, later on, as a poet? Are you still out there in the wilderness felling trees, stacking cords, and writing poems? I imagine these things go together — hand in glove — and that the writing couldn’t have happened the way it did without the wood falling the way it did.

2

Bob Arnold: Hello Gerry! I think it only fair that we let folks know that you are in Florida hidden away along the coast, while I am in the woods of Vermont. And amazingly, we have never met, though we have corresponded for almost four decades. We also have a mutual love and connection to the Berkshire Hills — I was born and raised there, and you had various stages of your life there, including the start of your family. I met your wife Lorry as a kid while I prowled the one lone main street of Lenox, Massachusetts, having hitchhiked south from home and waiting for The Bookstore to open in its old location on the sunny corner. Back then you had a few small collections of poems out, with eye-popping endorsements from Gary Snyder and Philip Whalen, which I coveted and saw as the natural touch of an honest poem. I believe we haven’t met, to keep the anticipation wild, and likewise the correspondence, running on a similar tangent of talking to one another letter to letter. Let’s keep it up.

Bob Arnold, 2007, in Carson’s music store. Photo Susan Arnold.

3

I plan to answer these questions all in one day. I’ll answer one and then go back outdoors and do more work in the gardens and in the woods. I think best on the move. Once I feel good with what sense I hopefully will make in my head, I’ll dip back into the studio and write out another reply. Yep, it’s the studio I built with my young son Carson… windows wide open today and an unusually mild and dry July day is passing through. I’ve had hours of quiet since dawn, so I think I’ll play some scattered tunes, while writing, by Maria de Barros, Roy Harper and this Scottish group my good friend Thomas Clark sent from his home called King Creosote.

4

Okay, to your question. I’m a seventh generation lumberman, if anyone is even counting any longer. My father was a proud historian of the Arnold Lumber history, which was at one time the oldest family lumber business in America. Established in 1788. Elisha Arnold was one of my great-greats, a Revolutionary War soldier and sawmill operator on one of the northern Berkshire water powered brooks, where he set down the roots. He was the son of Thomas Arnold who came to America in 1660 and settled in Watertown, Ma. Elisha was followed by a son of the same name, then his grandson Henry Arnold who was the kingpin of the lumber chronology — fathering two sons who were able sawmill and woodcutting adventurers like their old man, and good with horses, too. Henry manned the mountains in the Berkshire valley leading teams of choppers up Mount Greylock (about the same time Melville, in neighboring Pittsfield, was dedicating his book Pierre, or the Ambiguities to the same mountain). My family was the first to cut a wagon road to the summit of the mountain fetching for timber.

5

Back in Adams, son William entered the lumber life at age 14 and was developing an expansive sawmill business, turning out barrel staves and heads for the local lime quarries, plus boxes for area businesses, and of course sawn lumber. By the turn of the century murky photographs of the sawmill look like a sprawling muddy dooryard of high-rollers, logs piled sky high and the men of Adams were put to ample employment. My grandfather Robert was son of millwork genie William and by then he would develop where his father started, taking in the last stages of saw millwork and seeking for more and more sources of supply, mainly from the Great Lakes and Tanawanda regions… and this would expand to the west coast timber giants like Weyerhauser by the time my father, also Robert, stepped in straight out of the infantry of WWII.

6

Little “Bobby”, me, came into the lumber business picture in the 50s–60s when Weyerhauser, western spruce, eastern softwoods were stockpiled in a vast backyard (for a kid) in pretty much the same location as the old sawmill. The logging life was long gone but a few of the characters of that era were still around, none the least being my grandfather, now a banker and lumber magnate, ruling the roost with an earned bald-eagle eye. I’ve seen photographs of him as a young man in the woods on snowshoes. I’m sure I would have liked him then. As an old man he cruised the town in one of his two Cadillacs, but he wasn’t above stepping out into the dusty gravel lumberyard to make one of his spot inspections in fine dark overcoat, top hat, and to see-to how we were piling the lumber back there, gang-planked out of boxcars from the far west coast. He wanted the lumber stacks laid up straight and true on the butt ends. He’d show up and run the palm of his big hand down the face of the pine, spruce and fir boards wanting it all to feel like one. His eyes would let you know.

7

I was ten years old taking this all in. I’d work in that yard and later on carpentry crews around the Berkshires and southern Vermont until age 19, always after school and during the summer months. The labels as magic words still in my head to this day were Bird shingles, Lowe Brothers Paints, Delta power tools, Anderson Windows, Weyerhauser 4-Square Lumber. Those product sales helped raise my father & mother’s family of four kids, putting a few through boarding schools, summer camps, and we all got a deep taste of the lumber business. The other three kids took best to the business side of life. Whereas I took best to the wilderness side, a bit like great great grandpa Henry.

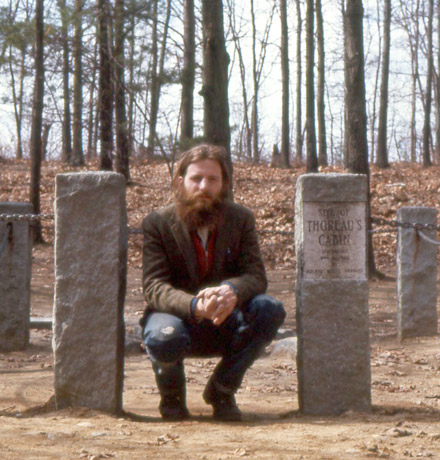

Bob Arnold at Walden Pond, 1975. Photo Susan Arnold.

8

Remember, it was the mid60s when everything crashed landed into one glory fireball of colors, and fortunately for us, no fatalities. I discovered the writings of Thomas Merton and John Steinbeck at age 14 and never looked back. Thoreau quickly followed. Bob Dylan was already in place through my older sister, and Dylan took me to Rimbaud and Pound, never mind Kerouac and all the Beats. To the ultimate Woody Guthrie.

9

It seemed every day a new writer or singer was found. Suddenly the wood I was touching in the lumber yard came from someplace. In this dinky little Berkshire town I was finding tremendous voices from a farther away wilderness, and their poems made sense with lumber smell, pitch pine, darkened knots, light majestical redwoods and cedar: those, of course, were Gary Snyder, Wendell Berry, Jeffers, Patchen and Rexroth. I can recall like yesterday finding William Everson’s The Residual Years with such a reverence on each page that I began to adopt it into my own drudgery jobs at the lumberyard. Suddenly I was old enough to sign up one summer on the carpentry crews which was about as close as I could get to the loggers and workers I read about out west (here in the Berkshires, in the once hotbed of logging and choppers).

10

The carpenters were the next best thing and I liked their style — sunburned lean jokers, in boots, with a million stories, showing up like gunslingers in the refined office and store of the lumberyard — and more often than not we’d come to work at the yard at 7:30 only to find the padlocked gate busted open with bolt cutters by the wily carpenters who were there at dawn needing materials and not waiting for us sleepy heads. I went to work with these guys, handsaw efficient pile drivers, always with a book tucked away in my lunch pail… and since I worked hard, the books were overlooked by the master-teasers.

11

I worked in the family business until I was 19 and drafted into the Vietnam War. As a war resister, I earned a conscientious objector status which I could have served out its two year stint in the Berkshires. But I was hungry for my own adventure deeper into the woods, to try my hand solo at building my own household in the trees. I applied to my draft board for a Vermont location and so received, and I’ve been here ever since — building with stone & wood, laying walls, gardening, woodcutting year-round, moving winters on those same snowshoes I saw my grandfather use in that photograph, and the poems abide.

12

2. The love of your life, beyond poetry, really, is your wife Susan. One girl, one poem, one place = Bob Arnold, poet. Why, then, haven’t you written a big book of love poems for Susan? Or have you (we just don’t know about it yet)?

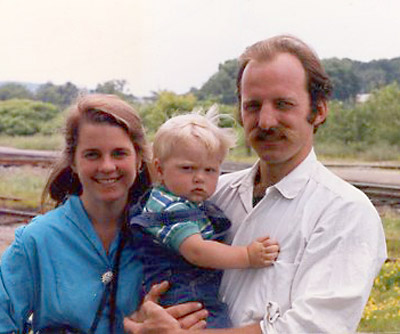

Susan and Bob Arnold, with son Carson, 1986: starting a family.

Photo Peggy Carey.

13

Cid Corman used to tell me over and over that all my poems were love poems. After forty books published all sizes and shapes and chiefly from the small press world — so good luck finding them — I’d say he was probably right. I may be the last person to have an opinion on the subject. Without a doubt before Susan, I was writing poems to some dream girl — this small town boy stuck now in a cabin in the woods at age 20 and no car, never mind no driver’s license, hiking in a couple days each week the 10 miles to the nearest town for work and supplies. Never touching the fashionable weed or alcohol or tobacco, not exactly a party animal, it was a stroke of luck that I ever found Susan. Or did she find me? After 33 years it all has smelted into love, family, son Carson, as daylilies by the hundreds in the yard we have planted and where I see Susan’s sandy hair now moving at this moment. We haven’t been apart one day or night in those 33 years, and I’m just afraid the love affair shows no sign of stopping; so I don’t see a book dedicated to specific love poems to Susan since it’s still on the go. I could write a poem down the road that I would be disappointed didn’t get into this collection you very generously harmonize for me. I guess it could happen, but I’ll wait for someone else to show it to me.

14

3. Readers sometimes see the connection between you, your writing and Robert Frost. You did your poetry with the net down — to use Frost’s metaphor for free verse — but your metrics are as tight as his in many ways. Was Frost an influence on Arnold?

15

Sure. But no more than cummings and certainly Kenneth Patchen who was much more wilder for my taste than Frost. Patchen’s steel mill body background, heavy brow in politics and against injustices, the whole Blakeian aspect of a singular love companion, his drawings and invented worlds. Just glorious. Thoreau was monumental, because we were both boys from the same state and for the first time in my reading, I was finding a writer who built a place and philosophy with his own hands. I was drawn to Wittgenstein first for his headscape of building aspirations, then into his philosophy.

16

To say Robert Frost in New England was as good as saying “Jack Frost”, the ice on our morning windows. Every walk of life knew Frost. He was about ruined for me by schooling that sing-songed his achievements. It was only as an older teenager I began to investigate his hardships of family and living. I took a drunken boat all of its own with his poem “Home Burial” and began to notice his well bit down lines from his poems to birches and mud-time that were as real as anything I had lived in. I went and found a copy of his second book North of Boston and after a few years of my own in a cabin with lamplight, I set it right down next to Lew Welch’s Ring of Bone. As much as I was drawn like a moth to the Frost lamp, never mind Welch, Robert Sund, James Koller, Lorine Niedecker and other backcountry surfers, I adored the experimenters and likewise urban types like Kerouac, Frank O’Hara, Paul Blackburn. Barbara Guest, James Schuyler, all the French and Spanish and finally into Asia… where I’ll never leave.

17

4. Are your themes quintessential Vermont? Do you see yourself as a Vermont poet? Or could you be just as happy writing poems in northern New Mexico? Can you take the kid out of the Vermont woodlot and keep him happy?

18

Oh yeah. When Susan put her eyes on me she thought I was out and out from California; or was this California girl just seeing things? She swears to this day and upholds this story. From 1965–70 I was so steeped in California poets and music I could recite for hours on end a litany of examples and places and people that certainly would convince anyone I must have at least visited the state for awhile and knew some of the digs? Not so. I wouldn’t get there until 1984. Susan and I took our first train voyages, of many, in 1979 to the Pacific Northwest and somehow missed going to the golden state. Don’t ask us why. It may have been our two decades long attraction to traveling always northward, often up into Canada anywhere, and the Maritimes. I believe the ’79 Northwest passage was an abbreviated version that originally included a jaunt to Prince Rupert. We made it to Jasper and maybe there wasn’t a train going in that further direction?

19

So far we haven’t been able to take the kid out of the Vermont woodlot for more than a few weeks… but those few weeks gone astray have been powerhouses writing poems, yes, from New Mexico and California. See my Go West and American Train Letters for two of the travel books. By the way, I love turtles, as does Susan (and I know you do too); so, you know, the house on the back.

20

5. You love trains and train travel and have written a book about your train adventuring, not to mention your travels north, south, east and west. Do you ever think of yourself as a travel writer … even in your own back woodlot, noticing the hawk trapped in the tree, the woodcutter’s shirt left on a branch?

21

Others have said I’m part travel writer, and I’m quite happy at their claim. Travel is a tremendous rush for me, even to this day. I traveled little as a boy, and I’m always reluctant to leave home. I can find paradise on a park bench, definitely in the woodlot — look up and see the redtail glide in that patch of blue and then it’s back to the green canopy of trees overhead. Like a streak of the old New England puritan work ethic in my poems, I like to earn my travels, save up passage, dream each inch out and map it with Susan in our heads, talk for weeks about it. We once climbed almost every range in western Massachusetts while preparing for a big trip out west… we’d talk our way up and back down the trails mapping out procedures of travel. After I met Susan it took some deepening years to expand our little clearing and cabin in the woods so our travels were throughout New England and the Maritimes. All in VW bugs, cheap to go.

22

Then the trains became an option and for the next twenty years, and mostso after Carson was born, we wanted to take him everywhere and see everywhere often for the first or second time with him. We packed him like one more duffel bag at age 4 with us to New Mexico, a night train we caught out of the Berkshires. We took at least another half dozen big-style journeys with Carson after that, often including car rentals from any old place, a bus, smaller trains, and pitching us like magnets always to the southwest and California, and then we’d compass away from some power spot where we’d easily catch our bearings. Heading from Taos to the Olympic Peninsula was one. Carson was always pulled out of school for these journeys Spring or Fall. We never strayed far in the summer due to outdoor jobs, and winter we always hunkered down beside the Vermont hearth.

23

After one winter we took a spring train ride to Washington DC to show Carson the old formed structures of democracy and art, then another train down through John Brown territory that swirled us to South Carolina and a reasonable rate automobile that zoomed us straight across to Santa Fe (power spot), picked up a new car, onward to Santa Barbara, Susan’s old home. Carson in the back seat sitting bemused, bewildered or beaming.

24

6. Of the New England poets who seem to wear the Frostian mantle is there one, in particular, whom you admire?

25

I’ve known many New England placed poets, and while I wouldn’t want to crouch a label onto them as “Frostian”, others have. They may reject the title. The one I like to think of as the closest example of Frost is Lyle Glazier. He’s little known and of course this all makes his poetry more appealing to me. He also knew Frost, or at least met him, and could recite his poetry (or Shelley’s) on request. His own poems were hard won nuggets off the farm life he knew in the Connecticut River Valley of Massachusetts. Both his parents were suicides when he was a boy, so he was virtually abandoned to his other brothers and some shady perversity and genuine country life with his elders.

26

Hayden Carruth had the expertise as a judge one year to pluck out of the rum of manuscripts for the Vermont Council for the Arts Lyle’s best book of poems, Two Continents, showing this Frostian glean. This is the Frost before the fancy years of fame. There are other poets in New England I could with no hesitation nod to as the descendant of the fuller Robert Frost. However, for the Frost of those lean, stone well water tasting poems, the real algae and mucky muck, the lyrical genius, I say Lyle. The other one would be Robert Francis, but everyone had better already know that.

27

7. Were you thinking of Frost’s “Out, Out — “ and the boy who bleeds to death in a chainsaw accident when you wrote your poem about the boy who is struck by lightning?

28

No, I wasn’t. At least not at all consciously. It’s been brought up by others who have read my poem, or taught the poem, as a direct kin to the Frost example. My poem is a true story with a little embellishment for the lighting power thrown in. A poet gets excited when telling a true story. I imagine Frost’s poem is pretty true, too. These things happen in rural life. Mine came from Colrain, Massachusetts when I heard the news about a local boy who had been struck out in the farmyard during a thunderstorm from the day before. I was down at the local sawmill along the river where I live, when such was still in business, picking through new sawn lumber and talking it up with the sawyer who I was friends with. He told me some of this story.

29

The part about the lightning striking the boy, came to me while I was writing the poem, from a summer camp experience as a youngster in the Berkshire hills when I literally saw lighting strike a tall, white pine tree and split it down the center. I was then living in a small, creosote-stained log hut with eight other campers as far away from the camp center as possible. No electricity, open shutters without windows or screens, bats flying in and out of the hovel all night long. You got out your flashlight to go outdoors to take a leak and that’s when I saw the lightning strike right in front of me. Holy shit. Years later, it came to me for the poem. Naturally I’ve seen this farm boy all my life, and the farm dog, and the maple syrup and the old timer and the kid helpers were much like me at the time with my neighbors when I lent a hand with their chores.

30

8. Do you consider yourself a patient person? Your poetry has a deep-seated sense of patience, like you would out-wait a thousand snows to see the brook bubble once in spring… is this really in your nature or just in your verse?

31

I can’t believe the patience isn’t in me if it’s reached the poems. I am only drawn to poets who to my sense of things have earned their way line by line. In other words, I am terribly disappointed if the poem and the poet don’t match up. I don’t look at poetry as something that is supposed to be written, nor is it a job, or some business. I find most of that poetry unreadable and actually unheard of. If there is a patience recognized, or an anger, it has to be a stripe down the hide of the author.

32

But then again, you ask me a question I can’t possibly answer because I have seen myself wait a decade to finish certain poems, wait days on end for the right word to place into a line, no hurry in the least to produce a finished book. I practice stencilling and have decorated about every room in our house that I slowly rebuilt from a 17th century farmhouse original. I’m happy as a clam for years on end wearing the same clothes and boots and kissing the same lips. Building and building those plodding tracks of stone walls. But I wouldn’t say I have dowser wisdom patience. I still have alot of kid left in me. I’m no fan of waiting too long in lines or behind stop lights; though that may be more about modern life.

33

9. Comment, if you will, on your second generation Irish background. Is that a factor in your being a poet?

34

I haven’t unearthed any poets per se in my mother’s side of my Irish background, but they are all, each one, a cast of characters. They have all been a life long influence on every part of my being, whether poetry as song, dance and celebration which this bunch is prone to be. I’m speaking about my mother and her siblings and parents, rather than my generation. The elders were carpenters and bakers and cops and mothers with large families, and I can never remember a sticky point, even when I turned up with long hair and long beard as a youngster and dicey politics to share with a crew that launched from Belfast together after WWII for the open ground sweep of America. Maybe they saw in me someone who loved this country all the same, the truest roots.

35

It was my grandfather Scott, the baker and policeman from Belfast, who introduced me to the woods. None of my lumbermen Arnold family knew a thing about the woodlands by the time I showed up hungry to dip into Eden. They were businessmen, contractors, bankers, eventually realtors. A tree was a tree was a tree to them. Old logger Henry Arnold would have shuddered right alongside me listening to this bunch. It was the Irish sports, even though middleclass in America and in their suburban nooks, who had the gift for adventure. My uncle Brian, as a teenager, built a treehouse to beat all treehouses at the time in our area — forty or maybe it was fifty feet up a wide pine tree. You got up there, if you had the skill, by climbing a rope. I was easily pulled into his James Dean lifestyle, including roaring around as his companion on his motorcycle all the small town neighborhoods.

36

His older brother David became my first class ticket to what a carpenter was — lean, playful, driven and accomplished. My grandfather worked in factories, later as a janitor in a bank, and when my grandmother passed away he moved into a trailer park without nary a complaint. Spread honey every morning on his toast. Rode his simple bicycle, as he often did on his bakery route in Ireland, up to 25 miles in a day. Naturally, in my eyes, my mother and my aunts were all beauties. If not in looks then in humor and turning their eyes. My grandmother, poor soul, died at a younger age than all of them and probably because of them! It ain’t easy keeping a circus in check. In the right company they all love to talk, laugh, and sometimes real nonsense; me too.

37

10. What makes you angry? And do you ever express that anger in your verse?

38

We’re in the homestetch, Gerry. Instead of taking a break after each question and going out to work and returning for a next question from you… I’ve plowed ahead in conversation with you during questions 1 to 9. I thought to play music but ended up playing, so far, only King Creosote (what a name for anyone who lives by woodfires!) and then forgetting all music entirely. I was with you. My stonemason’s back started to act up after typing/talking for three straight hours. Susan offered to give me a back rub. Did I refuse? Are you kidding!

Susan and Bob Arnold, 2007. Photo Hannah Greaux.

39

I asked her about this anger question and she couldn’t come up with any answer for me (the only one I asked her about) except some classic worker relationships between tools and man. You know, chain saw not starting; lawnmower stalled in high hot grass; whacked in the face with brash unwieldy brush. Blow my top? Yes, now and then; much more when younger. I took it personally when a chain saw I was close friends with abandoned me way up in the snowy woods and refused to start. I kicked the chain saw all the way back down the trail with the side of my boot until we both stumbled into the dooryard no better and a little more sore. It was proving a point, I believe.

40

I guess socially and politically what makes me angry is the big bad old world called injustice. I grew to detest Nixon, Reagan, Cheney and that Punk I refuse to qualify with a name. Is that angry enough? Others, like the Clintons, just make me a little sick. I believe I’ve only written two angry poems and both were political and both dealt with the same crud of the earth — Kissinger and Pinochet — who were responsible for the death of body or spirit of two of my Chilean heroes Victor Jara and Pablo Neruda. Those poems are “Faraway, Like the Deer’s Eye” and “Face of a Dictator”. Walter Lowenfels took one for his anthology For Neruda/For Chile. And then, unfortunately, Walter passed away, and I couldn’t send him the other one.

41

11. You’ve spent a good measure of your life alone in the woods; well, alone with your wife Susan. Are you entirely self-sufficient like Helen and Scott Nearing, the back-to-the-earth gurus of the Sixties?

42

I never met the Nearings — very early influences on my life for outdoor life and work — though not so much their social habits. Helen Nearing and I did exchange our stonework books after Scott passed away and I’ve read everything she has ever written and a good bulk of Scott’s work.

43

No, I have no interest in being entirely self-sufficient in the Nearing model, which of course is filled with loopholes and discrepancies of the story. Marriage infidelities by Scott Nearing were common. His ruling, some, with an iron hand was another complaint. They also had a trust fund of some sort which makes living and bossing a principle, so I’m told, quite a bit more easier to manifest. There is no doubting their focus and tremendous accomplishments, but I’m not certain what sort of “good life” it was. No such trust fund is in the Arnold household.

Bob Arnold working with stone, 2007. Photo Susan Arnold.

44

We have what we make, and where we have been gifted with resources by friends in the workplace (tools, jobs etc) or in the poetry trades (bookselling and publishing) it’s been a mutual benefit of receiving and giving forth in return. I worked many years at bartering with those who still knew that talent. We keep a modest garden, burn chiefly all firewood, and for decades even heated all our water and prepared each meal by wood cookstove. We supplement now with gas and wood, and finally put in a shower after 30 years of hauling hot water buckets to the tub. And for years before that water drawn by bucket right out of the river. We drive used vehicles and rarely use them, staying close to home and finding work at a bicycle or walking distance.

45

Plus we run the bookshop and publishing outlet Longhouse all from home. It took a computer to put us in better touch with that world, and so be it. We don’t fight practicalities. We adore the word used, as in books, clothes, music, lumber, tools, hardware, furniture — and what we can build, sew, weave, bake or draw by hand, we do.

46

12. How do you view yourself as related to the American scene? Poet- dropout- woodsman- stoneworker- editor- publisher- bookseller? None of these?

47

I agree to all the above except the word “dropout”. I’d fuss at that word. If anything, I believe in activism, community, relating and the importance of response. I see a poetry world becoming larger in its context with all the world, but shrinking in their shared bad habits of bonding as a clique, schools, or fixed business — poetry must stay freer. So yes, I guess the get-up is a woodsman from family heritage, working the trades of wood and stone. The editing of Longhouse for over 35 years now, designing and printing small handmade booklets of poets from around the world. The bookseller arrived out of my voracious appetite and love for books and supplementing our lifestyle of working class. And my poems and other writings, after all of this, come what may.

48

13. Comment on blackbirds.

49

I knew one. A long, long time ago. I was building a stone wall and doing treework for a couple in the village two miles up river from where we live. We were a newly married couple and had just gotten married in the old and rarely used church in the village, more like a large white chapel. The grass had grown knee high and the windows were dingy. We found out we could have a ceremony in there since my friend who hired me as a CO for his Episcopal church as sexton, was also our landlord in the cabin we lived in for free, bartering our labors on his land at stone walls and carpentry upkeep. A few years later we’d be offered his house and this cabin and the whole ball of wax, so not a lick of our work was ever wasted… it all pointed ahead.

50

Our friend was more than happy to marry us in this church. We took up our scythes and mowers and soap buckets and spruced the place up, and two days later at 7 in the morning we were married. The family lumbermen and Irish and military all came. The couple in the village were old inhabitants and trustees of this church, and they liked everything they saw and gave me a job, building stone walls on their property, repairing those under their barns, felling particular trees. It was very good work for a newlywed, and once upon a time communities really welcomed newlyweds who looked like they might stick.

51

Midway through these jobs, this couple also offered us a puppy, a large floppy-eared lab by the name of Spooky. Spooky wasn’t making it where these people also had a home in town and they wondered if we would like her. In our minds we saw: big dog already, small cabin, the two of us, but we both loved dogs so why not give it a try. We took Spooky home after that day’s work. Our emotional lives were pretty much as young as the dog, and in quick fashion she wasn’t settling in at all with ours, so after supper we thought we should take the dog back to her former owners and call it a good try. I was then driving an illegal 1950 Dodge black pickup truck on only the back roads. A friend had driven it up from Rhode Island as a gift and the registration ran out within the week, and I wasn’t legal driving anyway and whatever, so why bother legalizing the truck. We all loaded into the old coot, pulled the choke, got it to turn over and oh it purred so nicely when finally running. Out of our glade and onto the dirt road along the river we went back up to the village, a most gorgeous drive at the end of the summer in the evening hours. 20 mph. We don’t want to take little Spooky back really, and she’s now kind of wondering what all the fuss is about, and so halfway up laying between us she decides to conk her big head down into my lap and turn her one eye up to me. Susan now found her irresistible, and so did I. We turned around in Don Squires battered dooryard, our nearest neighbor, and headed the truck back home, both of us now stroking this immensely gentle black dog between us. Not at all “Spooky” to us in appearance. She was now “Blackbird.”

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/34/hausman-iv-arnold.shtml