Philip Metres

reviews

d.a.levy & the mimeograph revolution

edited by Larry Smith and Ingrid Swanberg

264 pp. Bottom Dog Press. paper. isbn: 1-933964-07-3

This review is about 7 printed pages long. It is copyright © Philip Metres and Jacket magazine 2007.

1

Ever since I moved to Cleveland six years ago, I’ve been followed by d.a.levy. His poster-sized image — with all the gravitas of those iconic Warhol images of Che Guevara — looks at me every time I walk into Macs Backs Paperbacks, one of the last remaining independent bookstores in town. His voice is uttered in low adoring tones at local poetry readings. Recently, the 60th anniversary of his birth was recognized, and in 2005, Levyfest was held. Was this levy just another iteration of the Famous Local Poet, whose fan base spanned the geography of a postage stamp but whose devotion was outsized, mystical and unquestioning? I worried that he was a third-class Allen Ginsberg, whose poems — unlike Ginsberg’s best works — now emit only the moldering whiff of the Sixties.

levy poster

2

Yes, d.a.levy & the mimeograph revolution, edited by Bottom Dog publisher Larry Smith and Ingrid Swanberg, portrays levy as both Cleveland partisan and descendant of the Beats, but it argues convincingly for his cultural importance as both poet and publisher, and artist and book-designer, as proto-mystic and political scourge. This festschrift/compendium contains poems by and for levy, photographs, a biographical chronology, interviews, reminiscences, scholarly talks, critical essays, full color prints, manifestos, and a full-length DVD, “if i scratch, i write” by Kon Petrochuk. Petrochuk’s film — a haunting collage of interviews, Cleveland footage, and readings of levy poems — is by itself worth the purchase price of the book.

3

Dead at 26 in 1968 (from suicide), levy nonetheless left a mountain of work and a scattering of loyal friends who, like us, could only wonder what he could have done, had he lived longer. Mark Kuhar captures the manic energies, the multiple sides, the irreducible contradictions of levy:

paragraph 4

Since his death in 1968, we are still trying to unravel the mystery of d.a.levy — who he was, how he accomplished so much in so short of a life? Equal parts poet, artist, cultural figure, boo-hoo of the Cleveland, Ohio industrial wastelands, local conscience of the 1960s, psychedelic prophet, beat street hustler & one-man carnival sideshow, cultural entrepreneur, patron of the down-and-out and the young and emerging, performer, gypsy angel, wandering mystic Bodhisattava of the East Side, genius, lover, first amendment martyr, pure dharma consciousness (maybe too pure for this world) (38).

5

I’m not ready to call levy a genius; for every line that vibrates, I see others that are leaden. His poetry, republished by Mike Golden’s edited The Buddhist Third Class Junkmail Oracle: The Art and Poetry of d.a.levy (1999), occasionally languishes on the standardized page. (Part of the thrill of reading levy was the sense that almost no one else — and certainly, no mainstream publisher — had discovered him.) Yet levy’s poetry and art demonstrated enormous energy, raw talent, and great instincts — despite a high school education and living his entire life in the “backwaters” of Cleveland, he seems to have sniffed out the major poetic and artistic experimental movements of the time — beginning with the Beat poets, but extending into the various avant-garde experiments with collage, concrete/visual poetry, and symbolic action.

6

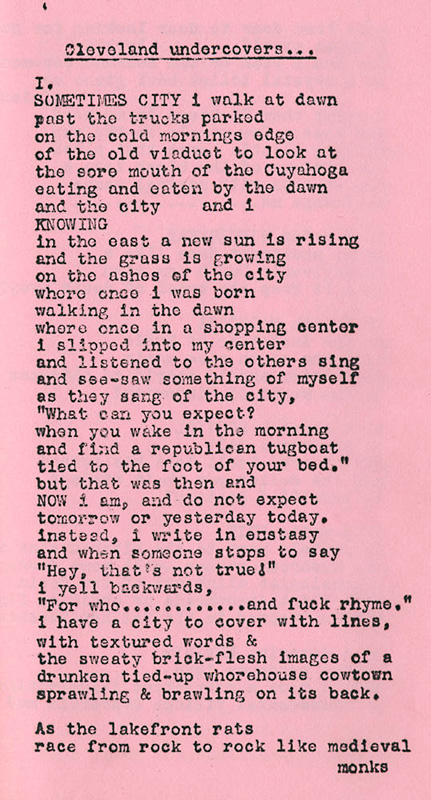

What endeared him to his friends and partisans was not just his underground poetry, but that he did it as a Clevelander, and someone who would never leave. He didn’t want to be a great poet; he wanted Cleveland to be a place where great poetry was made. Arguably his first major work was a book-length long poem called Cleveland undercovers (1966), which attempts what Sandburg did for Chicago and Ginsberg did for New York and Williams for Paterson, New Jersey — to sing the ineffable spirit of a city, even if the city is a “necropolis.” Here’s the opening:

7

The opening shows levy’s inheritance of the Whitmanic trajectory of American poetry — from Sandburg’s rhetorical air (“sprawling & brawling on its back”); to Williams’ antipoetic images of grimy urbanscapes and sense of line (“cold mornings edge/of the old viaduct”); to Ginsberg’s transcendental optimism (“where once in a shopping center/i slipped into my center”). In its samizdat printing, with its half-inked words, the poem captures the relentless desire (even duty) to own the city that has owned him: “I have a city to cover with lines.”

8

Ingrid Swanberg’s critical essay on this poem in d.a.levy & the mimeograph revolution makes claims for levy as a kind of Eliotic poet — suggesting the poem’s various possible allusions to the ancient and modern poets — thus translating Cleveland from an industrial waste land into a “Waste Land” — redeemable because it is finally not simply covered in soot, but “in lines.” levy’s adoption of the authorial initials “d.a.” (always typed in lower case, without spaces) seems to evoke both that British tradition and thumb its nose at said tradition, since a “d.a.” at the time would be understood as a “duck’s ass,” the haircut of choice for 1950s male rebels.

9

In her otherwise grounded and informative introductory essay, “No Last Words,” Swanberg makes the dubious claim that “levy’s greatness lies in that...his commitment to poetry is a complete one. Everything else is secondary for him, and it is this that sets him apart. It sets him apart from the poetic and political movements of his time...that tried to make the poem serve something else” (83). After all, it was levy’s outsized expectations of poetry’s transformative possibilities that contributed to his disillusionments — his desires were grandiose: to make Cleveland literary, to battle the authorities, and finally, perhaps, to end what he called his addiction to the culture.

10

levy’s increasingly poisonous confrontation with the authorities, that began with various exhortations to use drugs (following the lead of Ginsberg and Ed Sanders) and led to his arrest on obscenity charges, caused a crisis in his own poetry that did not always lead to more interesting work. (For the full story of his absurd hounding by the police, read the book.) His “letter to cleveland,” for example, echoes Ginsberg’s polytonal “America,” but without its buoyant (and, arguably, redemptive) sense of humor:

11

cleveland, i gave you

the poems that no one ever

wrote about you

and you gave me

NOTHING...

cleveland i gave you

poems that no one else had time

to write

& you arrested me

AND I DON’T EVEN CARE

(39)

12

The weariness of the voice, the lack of rhetorical force, dramatizes levy’s own inability to surmount what rapidly became an exhausting and ultimately suicidal confrontation with the Cleveland media and police. levy comes to represent, at least in part, one of the Ginsbergian “best minds” who became a casualty of the Sixties — not just the government’s repressions, but also the insatiable desire for freedoms without consequences. Perhaps I am reading in hindsight, knowing that a shotgun blast to the “third eye,” ended levy’s story. His own friends, after all, struggled to support him in ways that in retrospect may have contributed to his outsized hopes for poetry as a transformative (even revolutionary) cultural intervention. Larry Smith recounts the story of Jeanne Sonville giving out “$5, $10 and $20 bills to people at the Wade Park Lagoon, where levy passed out the Oracle, instructing them to give them to levy, who accepted them with amazement” (53).

13

Despite his relative isolation in Cleveland, levy’s work at his renegade press led him to literary and personal correspondence with underground poets throughout North America — Levy’s many literary correspondents included Ted Berrigan, Charles Bukowski, Allen Ginsberg, and Ed Sanders, among many others. His publications (both of his own poems and those by other poets, not to mention the numerous magazines he created) make him a key figure in the mimeograph revolution and in book arts as well. Karl Young, in “At the Corner of Euclid Ave and Blvd St German” writes that “levy was almost completely alone in making mimeo an art form in its own right, and he certainly was better at it than anyone else” (163).

14

Joel Lipman’s informative essay, “d.a. levy & the Book Arts” argues that we should read levy’s contribution as an extension of Charles Olson’s notion of the page as a field of composition: “it’s in his understanding and exploration of the page as completely usable material where he exhibits important understandings and practices shared with artists of the book” (169). levy’s books have a homemade feel, occasionally sloppily so, yet they are also so frequently inventive in their use and re-use of materials. Just as he refused copyright, so too did levy refuse the standardization that comes with mainstream book publication.

15

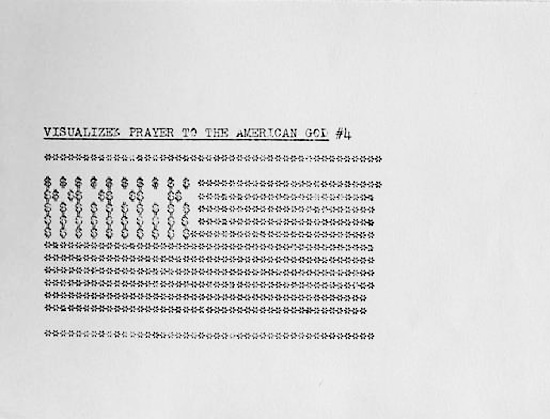

One of the turns of levy’s poetics comes when he reaches into concrete poetry, a mode that brings a visual and material sensibility to poetry, as a way of confronting the exhaustion of traditional poetic language. His Visualized Prayers & Hymn for the American $God$ (renegade press 1966) was dedicated “to americans fighting in foreign countries when there are battles to be fought in america.” Levy’s turn toward concrete poetry and collage had everything to do with the exhaustion of language that would turn the poets who are now called “language poets” toward a material poetics. In his introduction to his concrete poetry, he writes,

16

What DOES CONCRTE POETRY MEAN? People ask me! As close as i can get to it its meaning (for myself anyway) is after eons of time & boxes of poets writing singing chanting & shrieking love poems; people still prefer to kill each other. The PEACE poets arent getting their message across...so fuck it (234).

17

As Michael Basinski writes, in his reflection on levy and concrete poetry, “words had failed him, us, the world” (234). In “Visualized Prayer to the American God #4,” for example, we see a conscious melding of concrete poetry techniques to political and economic critique of the American dream — that the flag itself is built from dollar signs and asterisks is an unmistakeable image of a society driven by wealth-accumulation — everything else is asterisks:

18

Poets interested in writing for peace and against war have in levy a sobering reminder of the limits of words as such. If only levy had lived long enough to find that poetry — if not the society — was turning his way.

19

Yet levy was no lax peacenik. He was a provocateur of the first order, even though he had pretensions toward Buddhism and mysticism. For example, his “Cleveland Prints,” reprinted in the book, were abstract prints that were made by dipping condoms in ink. With titles like “Edgewater Park” (a beach in Cleveland), and “George Washingrom visits the Cleveland zoo” (where the first President is made of the condom imprint), “Cleveland Prints” collides sexual freedom against geographical and historical icons in ways that must have made polite society cringe.

20

There is an irresolveable contradiction at the heart of levy’s poetics, between the earnest longing for spiritual transcendence and the adolescent urge to tell the authorities to fuck off. Karl Young argues generously, for example, that “levy’s mysticism isn’t for everybody; but his expression of it should be an essential part of everyone’s understanding of what American poetry, including visual poetry and book art, has been and can still be” (151). At the time, one could see these two impulses (mysticism and rebellion) as intertwined. Certainly, Ginsberg made his name by making a poetry that both seeks spiritual union and challenges established orders. Yet in levy, the longing for transcendence — at least as it is registered in his poetry and art — feels like part of the strategy of the great “no” against his society.

21

Representing the levy partisans, Gary Snyder makes an argument for levy as a poet of place, whose commitment to Cleveland has an undeniably spiritual dimension. Snyder wrote: “I feel brother to levy not only as poet, but as fellow-worker in the Buddha-fields....Like the Sioux warriors who tied themselves to a spear and stuck it in the ground, never to retreat. Why? An almost irrational act of love — to give a measure of self-awareness to the people of Cleveland through poesy” (151).

22

In contrast, Ginsberg, interviewed for the Petrochuk documentary, saw levy’s Buddhism and other Asian religious allusions as facile, as political provocations of a society at war in Vietnam and against the East:

23

He had the books. He had the imagination. He had the poetic imagination. He had the humor. But he didn’t have the grounding in actual sitting for the symbols that he was talking about. He was talking about the Tibetan Oracle Stroboscope, Book of the Dead, Six Yogas, Super-Doctrines, Mahamudras. But that was all based on ordinary mind, sitting quietly watching your own anger; being aware of your own anger and not letting the anger of the cops, and not letting the anger of the civilization, get you (200).

24

levy’s anger is evident increasingly in his editorials and in his poems; he had every right to be angry at the houndings by police, media, and mainstream America. Yet his suicide almost feels like a capitulation to the very forces he fought to oppose.

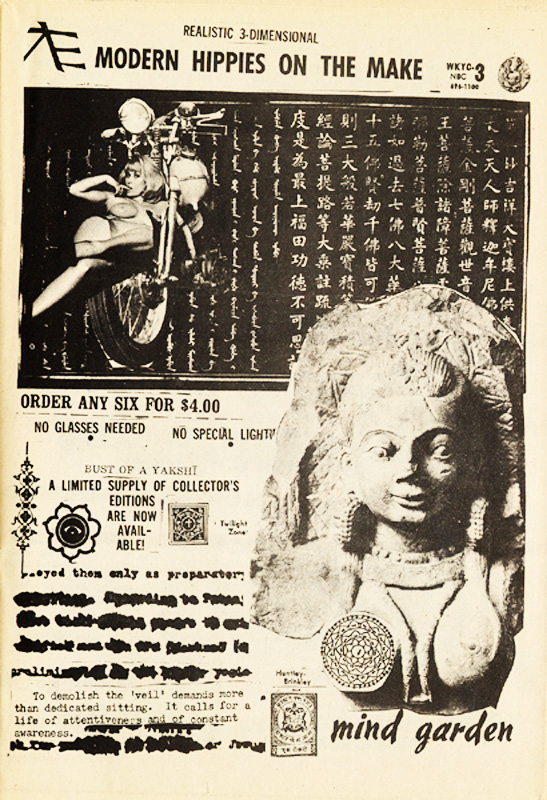

25

levy became a casualty of the times. Sometimes, his work feels very much like artifacts of that earlier age, particularly its heterosexism — which levy no doubt saw as part of a vision of sexual liberation, as others had at the time. Douglas Manson’s essay critiques levy’s collages, I think rightly, as “appropriations that exoticize more than they inform” (200).

26

Are we to read, for example, “Modern Hippies on the Make,” as a commentary on American society’s commodification of female sexuality, as an act of collage-rhyme between the naked woman from a skin magazine and an Asian sculpture, as a sacralization of nudity, as a condemnation of patriarchal religion, as a culture-jamming vision of globalization, as a sex-distracted advertisement for Buddhism, or something else entirely?

“Modern Hippies on the Make” from the tibetan strobo scope (ayizan press, 1968), image from The Cleveland Memory Project/Cleveland State University Press

27

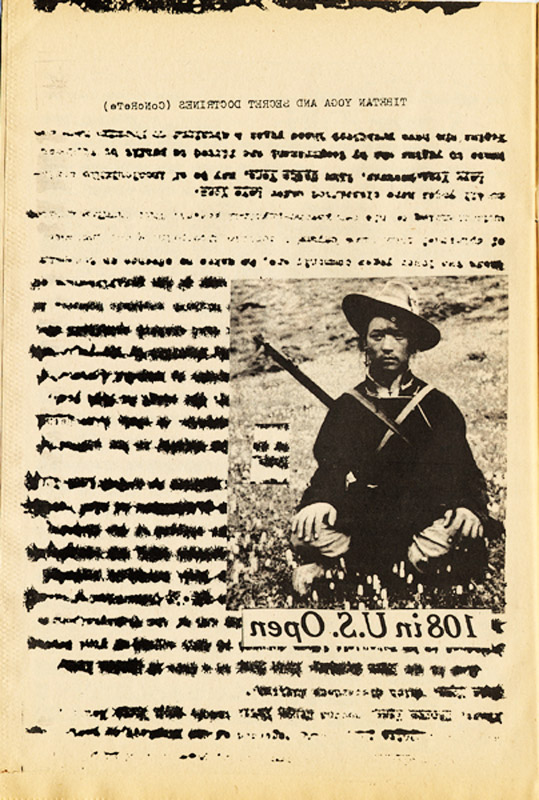

In these deeply contradictory pages of levy’s final project, The Tibetan Stroboscope (1968), published in the year of his death, levy was attempting to exorcise himself of the culture through the culture — even if he is ultimately unable to do so. The collages, then, become a dramatization of his own entrapment in the images from which he cannot free himself, even through language. Stroboscope’s acts of “destructive writing” — in which levy scribbles out or writes over texts — anticipates what is now a standard practice of experimental writing, seen in such works as Phillips’ Humument, Johnson’s Radios, Bervin’s Nets and Ruefle’s A Little White Shadow.

“108 in U.S. Open,” from the tibetan strobo scope (ayizan press, 1968), image from The Cleveland Memory Project/Cleveland State University Press

28

Joel Lipman describes these final poems as “demolished language and blotted textuality...is infused with tantric suggestions and ritualized horniness, comic bubbles and inky smudging suggesting redacted secrets or pages culled from an FBI file reluctantly disclosed” (172) — though it appears to have predated the release of such redacted FOIA files. (In this way, levy renders prophetically what the culture of secrecy would later divulge.)

legalize levy

29

In “108 in U.S. O Pen,” we see again how levy confronts the Vietnam War as the negation of holy texts, and of Asian realities as a kind of inversion of American cultural obsessions; thus the golf scores for the U.S. Open become, in an inverted caption, a kind of prison for an unnamed Asian soldier. The Open becomes a Pen, just as the claims for American-aided freedom for South Vietnam led to tiger cages and secret bombings of neighboring countries.

30

Though the book occasionally seems to suffer from redundancy — materials from the chronology then appear verbatim in essays, for example — such repetitions also dramatize the trauma of levy’s departure to his friends, and now to us, his readers. There are far too few stories of levy, because he was only just beginning when he ended everything. But we have Larry Smith and Ingrid Swanberg to thank for rehearsing what stories there are. Perhaps today — in an age when anyone can see and read levy’s work online at www.clevelandmemory.org/levy — to “legalize levy,” as the indie posters of the time demanded, we only have to read him.

Philip Metres

Philip Metres is a poet, translator, and scholar whose

work has appeared in numerous journals and in Best American Poetry

(2002). His books include Behind the Lines: War Resistance Poetry on the

American Homefront, Since 1941 (University of Iowa Press, 2007), a study of

the interactions between American poets and the peace movement, Instants

(2006), Primer for Non-Native Speakers (2004), Catalogue of Comedic

Novelties: Selected Poems of Lev Rubinstein (2004), A Kindred Orphanhood:

Selected Poems of Sergey Gandlevsky (2003). Forthcoming is a book of poems,

To See the Earth (2008). He is an associate professor of literature and

creative writing at John Carroll University in Cleveland, Ohio, where he lives

with his wife and two daughters. See

http://www.philipmetres.com and

http://www.behindthelinespoetry.blogspot.com

for more information. He can be reached at pmetres[ât]jcu.edu

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/34/metres-levy.shtml