This piece is about 20 printed pages long.

It is copyright © Jonathan Morse and Jacket magazine 2007.

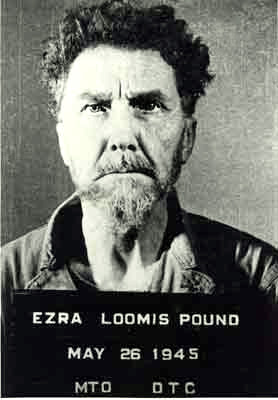

Ezra Pound, 26 May 1945

1

^

On July 11, 1954, eight and a half years into his incarceration in St. Elizabeths Federal Hospital for the Insane, Ezra Pound received a visit from his long-time poetic follower Louis Zukofsky, along with Zukofsky’s wife Celia and son Paul. Paul, not quite eleven years old, was already embarked on his career as a violinist, and at St. Elizabeths he gave a recital for Pound and some of his fellow inmates. The next day, Pound responded with a letter to Louis.

^

That composition displays Pound as he saw himself in relation to the arts: a stern but affectionate preceptor-at-large. The arts approached that teacher humbly, and he returned them to their artists scrutinized and improved. Celia was a composer, for example, and about her music Pound asked, ‘Question of whether C/ jams one LINERARR statement against another, or merely puts in chords?’ Proceeding to Louis’ poetry, Pound then opined, ‘damn if I see what yu wd/ lose by a rewrite making EVERY line comprehensible.’ And about Paul he spoke as one artist and father to another:

^

AND my prophetik soul / foreseeing: every time that brat gits a thousand $ bukks fer playing Weiniawski, Zuk will be beatin’ his breast and crying: why did I beget this cocatrice.

Only practical suggestion is that yu begin distinguishing between infantilism and MUSIC FER ADULTS. (Ahearn 209-10. ‘Weiniawski’ is Henryk Wieniawski, a composer of showy virtuoso pieces for the violin.)

^

Pound was one of the great critics, and in this letter we see him at his best: passionate, wide-ranging in his sympathies and eagerly receptive to the new, yet possessed of a profound sense of value. But before Pound was a critic he was a poet, and he was never satisfied with his own critical language until he had economized it. Within two weeks of writing this letter, for instance, he had reduced its contents to their essentials. ‘Mr. Zukofsky brot his ten year old son to play Mozart on the lawn a fortnight ago,’ Pound wrote to his confidante Olivia Rossetti Agresti. ‘ETC. INDIVIDUALS/ BUT......’ (Tryphonopoulos and Surette 163).

^

In the next sentence, Pound makes his point general and explicit: ‘I shd/ like to arouse ORA’s interest in history/ in biology/ in Luther Burbank, in eugenics/’ But that expository prose about racist theory is only a redundant gloss on the ellipsis following Pound’s ‘INDIVIDUALS/ BUT......’ It is hard to make a conjunction serve as an allusion, but that is what Pound has done here. A more prosaic speaker of English — for instance, Faulkner’s garrulous character Jason Compson IV, in The Sound and the Fury — would have filled in the ellipsis and finished the sentence. ‘I have nothing against jews as an individual,’ Jason explains. ‘It’s just the race’ (120). But when Ezra Pound hit his period key six times rather than write out more words, he was communicating a profound intuition about the silences that fall between feeling and thought, thought and speech. That ellipsis of Pound’s tells us this: some meanings are so deeply embedded in the social structure of language that they actually and literally can go without saying. Pound’s sense of Mozart on the lawn was something actually experienced, as compared with his fantasy of the word ‘Jew.’ But the word ‘Jew’ was a preemptive significance. It filled the cell of Pound’s mind with horror and silenced the echo of the violin.

2

^

More: for Ezra Pound, by the time he had reached St. Elizabeths, the word ‘Jew’ was experienced with a fully developed history of its own. It wasn’t just a defined sound with an immediately understood meaning; it was the trace of a number of meanings, slowly developed over time. In fact, we may learn to read Pound better if we think of that development as a verbal complex generated in response to a new word, and deployed by the same linguistic mechanism that brings forth poetic language itself. Specifically, the pair of phonemes that sound out the word ‘Jew’ may have functioned for Pound as an index, in Charles Sanders Peirce’s sense of the word: ‘A rap on the door is an index. Anything which focusses the attention is an index. Anything which startles us is an index, in so far as it marks the junction between two portions of experience. Thus a tremendous thunderbolt indicates that something considerable happened, though we may not know precisely what the event was. But it may be expected to connect itself with some other experience’ (‘Logic as Semiotic’ 108-09).

^

Pound never read Peirce, so far as I am aware, but the ‘luminous moments’ in The Cantos — those flashes of detail whose part in the poem’s great design is to signal that our sense of the numinous has acquired one more meaning — do function as indices. When he was writing poetry, Ezra Pound seems sometimes to have experienced words directly, without reference to their immediate denotative contexts. That is why some of the most vividly realized images in The Cantos are pure sound effects, like the circular saw in Canto 18 (‘whhsssh, t ttt’) or the loom in Canto 39 with its shuttle moving back and forth and its harnesses moving up and down: ‘thkk, thgk . . . thgk, thkk.’ Such words perform their work of meaning by evoking with a sense impression, not denoting with another word. The context of these evocations isn’t the locality of the sentences or paragraphs in which they are imbedded; it is the whole historical lexicon of language as such, in all its complex harmony. In that harmony the saw’s sound functions as an index, marking one of the moments when Pound’s incantation, ‘Make it new,’ has embedded itself in the sound structure of a new language, the language of economics. (Pound translates the saw’s economic onomatopoeia himself in the next line: ‘Two days’ work in three minutes.’) The sound of the loom in Circe’s palace is an index, too; it is a reminder of Penelope and the home to which Odysseus must return if his wife’s fabric is to be completed and western civilization is to have a written history. In general, it may be useful to consider Pound’s ideogrammic method as a way of moving through poetic space in a saltatory way, from index to index.

3

^

Cantos 18 and 39 date from the 1930s, but the urgencies of history and its language were even more pressing for Pound after World War II, when he slept behind bars in his nation’s capital. Fortunately, he found a tutor there: the same tutor who had been instructing Representative Thomas G. Abernethy of Mississippi. When Representative Abernethy addressed the House on June 7, 1957, the question underlying his remarks was Poundian in its scope: If history is a conspiracy against us, who are the conspirators? Thanks to his tutor, Representative Abernethy had an answer.

^

Representative Abernethy’s immediate concern was with what he called ‘integration and mixology’ (‘Civil Rights’ 8557) — specifically, the pending establishment of the United States Commission on Civil Rights. As he explained, ‘The snooping Federal Commission authorized by this bill, the additional personnel to be assigned to the office of the Attorney General, the voluntary employees of the Commission and all of the others that go along with this all-powerful investigatory establishment — all posing as the protectors of civil rights — will be nothing short of an assemblage of powerful Federal meddlers and spies created for the purpose of tormenting, abusing, and embarrassing southern white people’ (‘Civil Rights’ 8558). Yet that was not the worst. As Representative Abernethy had learned, torment, abuse, and embarrassment were the instrumentalities of a diabolical plan aimed at destroying far more than the regional culture of the South.

^

Abernethy claimed at first not to know where the plan originated.

^

I have noted with profound concern that it will be within the authority of the Commission to investigate allegations that citizens are being deprived of the right to vote by reason of religion. . . . We know that the bill is an appeal to curry favor with bloc voters but we do not know just what religious group it is with which some are undoubtedly attempting to placate and curry favor. (8558)

^

But of course this modest innocence was only rhetoric. Abernethy actually was in possession of exact information, and now he had come to stand before the Republic and name its name.

^

This civil-rights business is all according to a studied and well-defined plan. It may be news to some of you, but the course of the advocates of this legislation was carefully planned and outlined more than 45 years ago. Israel Cohen, a leading Communist in England, in his A Racial Program for the 20th Century, wrote, in 1912, the following:

^

[‘]We must realize that our party’s most powerful weapon is racial tension. By pounding into the consciousness of the dark races that for centuries they have been oppressed by the whites, we can mould them to the program of the Communist Party. In America we will aim for subtle victory. While inflaming the Negro minority against the whites, we will endeavor to instill in the whites a guilt complex for their exploitation of the Negroes. We will aid the Negroes to rise in prominence in every walk of life, in the professions and in the world of sports and entertainment. With this prestige, the Negro will be able to intermarry with the whites and begin a process which will deliver America to our cause.[’]

^

What truer prophecy could there have been 40 years ago of what we now see in America, than that made by Israel Cohen? The plan was outlined to perfection and is being carried out by politicians who have fallen into the trap. Many thousands in America today who are in no sense Communists are helping to carry out the Communist plan laid down by their faithful thinker, Israel Cohen. Truly, vigilance is the price of liberty. (8559)

^

Put into play by The Congressional Record, the Cohen quotation began circulating from newspaper to newspaper through the South. However, The Washington Star, where Abernethy had first read the quote in a letter to the editor, now decided to verify its authenticity, and on February 18, 1958, it published the results of its investigation. These established that (a) no publication called ‘A Racial Program for the 20th Century’ appeared to exist in any library known to the Library of Congress, (b) there was no Communist Party in England in 1912, (c) the only known writer in England named Israel Cohen had published not a word about race, communism, or the United States, and (d) both the quotation and its attribution to ‘Cohen’ appeared to have been fabricated by a former staff member of the Library of Congress, a man named Eustace Mullins. Invited by the Star to rebut these findings, Mullins evaded the request but ‘concluded his letter by inviting the Star to join his church in its crusade against the barbarous Hebrew method of slaughtering meat animals.’ Representative Abraham Multer of New York placed all this in the Record on August 5, 1958, and added:

^

[Mullins] was discharged years ago from his probationary job as a photographic aid at the Library of Congress because of his authorship and circulation of violently anti-Semitic articles. Mullins has, apparently, a marked propensity for phony claims and counterfeit creations. Some of his counterfeits include a speech by a nonexistent Hungarian rabbi, and a Lizzie Stover College fund — the fictitious Lizzie Stover being described as the Negro mother of President Eisenhower. . . . It is unfortunate that fabrications such as these, unless exposed by the truth, are repeated until they are believed. (‘Exposing a Fabrication’ 16268)

^

Half a century after that exposure, Eustace Mullins — still alive as of 2007, though 84 years old and in poor health — continues to exert his power over belief. In the 1990s one of his many self-published anti-Semitic tracts, Secrets of the Federal Reserve, turned out to be one of the plagiarized sources of another work of conspiracy theory, The New World Order, by (or ‘by’) the conservative statesman and educator Pat Robertson (Lind 105). Likewise, according to Ward Harkavy, ‘Mullins . . . once theorized that ‘Have a nice day’ is a code phrase used by Jews to mean ‘Kill the Christians.’’ That belief just must have a life of its own now, if only as an urban legend. Likewise, it seems possible that some of the contemporary candles-and-crystals opposition to vaccination originates with Mullins’ book Murder by Injection, which argues that modern medicine is a Jewish conspiracy.

^

And in the 1950s Mullins’ teacher and student was Ezra Pound.

^

One trace of their relationship appears in a letter that Marianne Moore wrote to Pound on July 31, 1952, thanking him for his hospitality during a visit to St. Elizabeths. The letter begins with a note of reproof for what must have been a prickly afternoon but ends in the cozy certainty of an old and unbreakable affection, this way:

^

. . . I shudder at false witness against my neighbor and if I do not attack you, then I concur in it.

Profanity and the Jews are other quaky quicksands against which may I warn you? You have seen turtles or armadillos, possibly, when annoyed and I sometimes have to be one of them. . . . I liked the young people. They transported me (conveyed me, should I say) to my Bus Depot, Mr. Del Mar regretting that he was unable to park and offer us tea, which I took it on myself to dispense in the form of Coca-Cola and orange juice, while discussing palmistry with Miss — . (502-03)

^

Miss — the palmist, I would guess, was Pound’s girl pal Sheri Martinelli, a constant presence at St. Elizabeths who had changed her name from Shirley for numerological reasons (Steven Moore). Miss Moore also missed the name of the other young person. Alexander Del Mar (1836-1926) was an economic historian whose name was frequently on Pound’s lips when he ranted about usury, but the obliging young man who helped Marianne Moore catch her bus was almost certainly Eustace Mullins. In 1952 Mullins was 29 years old and Pound was 67, but the relationship between them was reciprocal. In Mullins, Pound not only had a gofer; he had one last student for his Ezuversity. As Mullins told a radio audience in 1994 (truthfully; Pound’s biographies are full of witnesses’ accounts): ‘Oh I visited [Pound] every day for three years. And for three years, every day, he lectured me on world history! So that’s how I found out what I know’ (‘Interview’).

^

So in the year when Mullins drove out through the gates of the great poet’s insane asylum and conveyed another poet of the first rank to a bus station, one of the things he knew saw print. This was A Study of the Federal Reserve, an early version of Secrets of the Federal Reserve which was published (with an introduction by Pound) by two of Pound’s extremist political compeers, John Kasper and David Horton. More of the things Mullins knew were published in 1961 as a book called This Difficult Individual, Ezra Pound — a collection of first-person anecdotes and photographs from the St. Elizabeths years which has a right to be called only the second biography of Pound ever written, as well as a possibly partially true record of Mullins’ work as Pound’s primary contact with everyday Washington. Half a century later, This Difficult Individual and Secrets of the Federal Reserve still matter to academic Poundians and nuts who believe what Pound said. Readers who think of Pound only as a poet will find little to interest them. However, in another of Mullins’ books, a tiny pamphlet from 1951 called His Spirit-Tower, self-printed in an edition of just 99 copies, we can see thunderheads of the startle effect forming around Pound.

^

For His Spirit-Tower is a collection of Eustace Mullins’ poems. Most of its 43 unnumbered pages of text are taken up with lyrics like the one called ‘Devotion,’ which reads, in its entirety:

^

While your dear eyes disclose

their beauty in repose,

I ferment a testament;

Only real love is real,

That is all I can feel.

^

About which the only thing to say, probably, is that by 1951 the poor guy was old enough to know better. But elsewhere in the book a more interesting language regime prevails.

^

One aspect of the interest is that Mullins himself isn’t always visible in the language. Try to make out some details, for instance, through the haze around Mullins’ introductory ‘Note,’ which begins, ‘I am one of those few familiar with the operation of this democracy who are not Communists (a movement ALWAYS subsidized from the top level), millionaires; or political prisoners held in madhouses. I observe our government? because poets should not be dumber than other people.’ The politics and the paranoia of this note are Mullins’, of course, just like the book’s opening poem about you-know-who (‘Night and day the same dark eyes watch us: / friends, is it not time for some killing?’). But look as hard as you can through the actual words and all you will see are other words — words already cataloged by other writers, for readers of their own. The question mark after Mullins’ ‘government?’ and the ‘not dumber’ construction, with its combination of litotes and a term from the demotic, are imitation Cummings, and Mullins has only done with them what beginners do: borrowed another writer’s iterating equipment and used it to run off what he thinks are words of his own. In such cases, the beginner’s words are buried under a remembered library of the pro’s.

^

However, there are other passages in His Spirit-Tower where the language suddenly begins to take on a shape of its own — a shape that looks like Ezra Pound’s yet remains real on its own terms. This isn’t a visible, readable sign of a poet’s creative presence; Mullins only syncs Pound’s language from behind, the way storytellers used to do from behind the screen in Japanese silent movies. The author of ‘Devotion’ was never perceptible as a writer because his language was semantically indistinguishable from background noise; the penman who has gone semantically invisible and begun to sync poetry in Ezra Pound’s words is no longer exactly a man at all. Certainly he is no longer Eustace Mullins. But when he syncs Pound’s words he belongs, in so far, to the force in Pound that changed a language. At those moments, for a few lines, he becomes a poet, and a poet of a most interesting kind: a poet without a self.

^

Of course it is risky for a weak poet to attempt to assimilate a strong one. Another poem in His Spirit-Tower, ‘For Ezra Pound,’ successfully evades the danger for five creditable pages on the theme of the poet as prophet, only to end in disaster when Mullins tries to make the prophet speak poetry.

^

On the green sea the squirrel romps

to Gramps’ hand and the held peanut,

and the bluejay’s jealousy interrupts

the quiet conversation: the anarchist

pauses his recall of the whirled chaos,

sighs, ‘When Wilson sold this country out

we thought him our worst traitor;

But Roosevelt, the dirty swine,

has proved himself the greater.[‘]

^

This Difficult Character and the other biographies can fill in the sad exegetic details about Ezra Pound on visiting days at St. Elizabeths, fishing the lawn for squirrels with a peanut tied to a string while being merrily addressed as ‘Grampaw’ by the professional anti-Semite Eustace Mullins and the professional segregationist John Kasper and the economic crank David Horton and the Chinese-American white supremacist David Wang, who was shortly to commit suicide, and Sheri Martinelli, who was sometimes mistaken by visitors for another of the asylum’s inmates. Ernest Hemingway called them ‘dangerous fawning jerks’ (Carpenter 828). As we acquire the information, we will probably find ourselves getting depressed and embarrassed. But when we open His Spirit-Tower and catch Mullins trying to put rhymes in Pound’s mouth, we may think we have been offered a way out of our distress. Surely, we dare to hope, this entire episode in the life of language must be fiction. After all, the greatest master of English rhythm since Milton did know how to match metrical stress with logical stress. No, an iambic line by Ezra Pound really wouldn’t sound like we thought HIM OURworst TRAItor — and maybe Kasper and Horton and Mullins were fictions likewise. Comforted, we discount the actual historical truth about what was spoken on the lawn.

^

But then, reading on in His Spirit-Tower, we come to an altogether different kind of speech: Mullins’ four ‘Cantos after Pound.’ Here, startlingly, we seem to be in the domain of a poet rather like Ezra Pound himself — but a Washington-specific Ezra Pound, meditating on the Hay-Adams Hotel. Across Lafayette Park from the White House, that lodge for the powerful had been built within Pound’s lifetime on the site of Henry Adams’ mansion, and Pound had learned about historical dynamics from Adams. Possibly he taught Mullins the theory as well; at any rate, Mullins now signed his own name to a Poundian update on the young Adams’ Democracy and the old Adams’ Education of Henry Adams.

^

Henry Adams said I give it two more

generations

(humanity)

Two more generations

After 1900.

his house wrecked down

to make a salesman lobby whore hotel,

house that looked across green lawn

to the White House, where fools lived

(the crooks came later)

^

Yes, the prosody is simpler than anything Pound was writing in 1951. Yes, the District of Columbia geography is probably Mullins’ contribution. And no, Pound wouldn’t have written the catachrestic ‘wrecked down’ or the unvisualizable ‘salesman lobby whore.’ But the adonic meter of ’house that looked across green lawn’ has some of the power of Pound’s rhythm, and the parenthesis ‘(humanity),’ poised between empty spaces like brave little humanity itself, works. Suddenly, crazy prose has taken on the orderliness and dignity of a poem.

^

Of course there’s no need to explain Mullins’ luminous parenthesis as a miracle. Pound, who always wanted to be a professor, probably just helped Mullins with his writing. Almost sixty years later, however, the reciprocity of that educational transaction in the Ezuversity remains startling. We are to imagine Ezra Pound and Eustace Mullins, heads together, laboring over a manuscript: Pound teaching Mullins the ancient discipline of prosody, Mullins murmuring into Pound’s ear the creative lies he would later tell Representative Abernethy.

4

^

As to Representative Abernethy: a quiet back-bencher with a specialty in farm policy and a subspecialty in cotton, he represented Mississippi’s fourth and first congressional districts from 1943 to 1973 (‘Biographical Note’). In his long career, the only moments of political drama occurred during the Democratic primary of 1952, when he defeated the altogether more colorful Representative John E. Rankin, a flamboyant racist and anti-Semite who once physically attacked another member on the House floor (‘John Rankin’; ‘Battle of Washington’s Birthday’). After a quarter-century of peaceful retirement, Abernethy died in 1998, aged 95. Nobody now remembers the speech in which he channeled Eustace Mullins.

^

As to Eustace Mullins: by 2005 he was sharing a website with a man who believed that Hitler commanded a fleet of interplanetary flying saucers during World War II (‘German UFO Chatter,’ under ‘Sodomic Mind Control’).

^

Those updates are probably unremarkable. The culture of the American South has demonstrably changed for the better since the 1950s, and most of us will probably be immodest enough to say ‘I saw that coming’ about Eustace Mullins and the flying saucers. But as to Ezra Pound, who probably is going to be remembered centuries from now —

^

Almost immediately after Pound’s capture by American forces at the end of World War II and his aborted trial for treason, his family and a group of sympathetic scholars mounted a disinformation campaign aimed at winning his freedom and minimizing the damage to his reputation. By suppressing some texts from Pound’s oeuvre (such as, in the early days, the explicitly Fascist Cantos 72 and 73) and promoting others (such as, in the early days, a carefully expurgated collection of Pound’s wartime radio speeches from Rome), the campaign shaped a critical consensus which dominated the Pound canon for the next half-century.

^

In 1996, however, Pound’s companion Olga Rudge died at the age of 101, and then, finally, some uncomfortable old primary documents began making first appearances in print. In 1998, from Pound’s newly published letters to his friend Olivia Rossetti Agresti, we readers learned that Pound regarded Hitler as a tragic hero brought low by the fatal advice of his Jewish counselors (Tryphonopoulos and Surette). In 1999, from the newly published correspondence Pound exchanged with his wife after his capture, we learned that Pound was not only anti-Jewish but anti-Christian in the most credulously literal way, to the extent of saying his prayers to Apollo (Omar Pound and Spoo). Belatedly, we began realizing that the noble palinode in the Pisan Canto 81 (‘Pull down thy vanity’) may not depict Pound counseling himself but Pound denouncing somebody else, such as Winston Churchill. And then we began understanding the significance of what the St. Elizabeths psychiatrist Jerome Kavka had told us in 1991: a single magic word, Roosevelt, possessed the power to transform Ezra Pound from a lord of language to a gibbering, shrieking lunatic who couldn’t stop raving until he jammed his thumb into his mouth and bit down hard.

^

That too is startling. But we may now be ready to understand the two ways in which the startle reflex operates.

5

^

The first way is what underlies John Aubrey’s well known anecdote about Thomas Hobbes discovering the Pythagorean Theorem.

^

He was 40 yeares old before he looked on Geometry; which happened accidentally. Being in a Gentleman’s Library, Euclid’s Elements lay open, and ‘twas the 47 El. libri 1. He read the Proposition. By G — , sayd he (he would now and then sweare an emphaticall Oath by way of emphasis) this is impossible! So he reads the Demonstration of it, which referred him back to such a Proposition; which proposition he read. That referred him back to another, which he also read. Et sic deinceps [and so on] that at last he was demonstratively convinced of that trueth. This made him in love with Geometry. (Aubrey 150)

^

That love is the emotion that drives Keats’s ‘On First Looking Into Chapman’s Homer’ and Donne’s ‘To His Mistress Going to Bed’: the ever-renewing impulse toward discovery, which literally means an uncovering or revelation, and which bears in itself the desire to keep uncovering and revealing more and more, without end. True revelation ends only at the opened border to another world, such as the wide expanse that deep-brow’d Homer rules as his demesne or the eternal Platonic law governing the relationship among the sides of a triangle. It is an unconcealing of what Dante calls the love that moves the sun and the other stars.

^

When Malcolm Cowley saw the way Pound explored, however, he experienced nothing like Hobbes’s or Keats’s or Donne’s euphoria. Instead, he found himself watching Pound perform for himself on a stage partially concealed from his audience. Then, when the time came for Cowley to applaud, he found that he himself could no longer perform well. He had not been invited to become one of stout Cortez’s men, looking at each other with a wild surmise; he had merely been shut out.

^

Pound was then [summer 1923] living in the pavillon, or summer house, that stood in the courtyard of 70bis, rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs, near the Luxembourg Gardens. . . .

‘I’ve found the lowdown on the Elizabethan drama,’ he said as he vanished beard-first into the rear of the pavilion; he was always finding the lowdown, the inside story and the simple reason why. A moment later he returned with a worm-eaten leather-bound folio. ‘It’s all here,’ he said, tapping the volume. ‘The whole business is cribbed from these Italian state papers.’

The remark seemed so disproportionate that I let it go unchallenged, out of politeness. ‘What about your own work?’ I asked. (120-21)

^

This claustrophobic episode comes from the 1951 edition of Cowley’s memoir Exile’s Return — a thorough revision of a text first published in 1934, before Cowley’s question ‘What about your own work?’ acquired its inflection of historical irony. In 1951, with the controversy following Pound’s Bollingen Prize just three years in the past, readers would have understood Cowley to be writing sorrowfully about a poet who failed to understand what his work should have been. But in 1934, Louis Zukofsky was placed in the uncomfortable position of confirming Cowley’s perception before it was time to do so.

^

In the desperate early days of the Great Depression, a number of Fascist organizations sprang up in the United States, some of them organized along paramilitary lines. One of those, the Silver Shirt Legion, was founded by a commercial writer, William Dudley Pelley, who promoted his ideas in a journal called Liberation. In the spring of 1934 Zukofsky seems to have sent Pound a copy, perhaps with an ironic cover note about Pelley’s conspiracy-theory anti-Semitism. Pound’s reply was disconcerting. On May 6, 1934, he wrote, ‘I spose Mr. Pelley will be annoyed wiff me fer askin if all bankers iz jooz? just like Moike iz. but still.’ ‘Moike,’ the editor’s note tells us, was Michael Gold, the popular author of a 1930 novel about New York’s lower east side ghetto called Jews Without Money. To Pelley the terms ‘Jew’ and ‘banker’ were evidently synonymous, and the part of Pound’s reaction up to ‘but still’ seems to signal that Pound understood Zukofsky to be a Jew without money himself. As of May 6, 1934, that is, Pound was capable of seeing Louis Zukofsky as an individual, having a history which meekly asked to be read without preconception.

^

But the next day, in the same letter, Pound was not speaking to Zukofsky but performing for himself in Zukofsky’s vicinity. The drama was a reenactment of some fragmentary scenes from Pound’s memory, such as the scene of his dismissal from the Ph.D. program at Penn 27 years earlier. Reenactment, after all, had been his business from the beginning of his career, as a teenaged imitator of Browning’s dramatic monologues. By 1935 he would be able to condense his life’s work into a definition and plan: ‘An epic is a poem including history’ (Social Credit 5). What that entailed for poetry, and for Louis Zukofsky too, was this: the enterprise of Ezra Pound was to reimagine external realities, then subjugate them to the control of prosody.

^

Seriously, yew hebes better wake up to econ/ / /why don’t the rabinical college start delousing the Am/ Univ. system the suppression of history etc.

Speakin to you aza anti-semite??

If you don’t want to be confused with yr/ ancestral race and pogromd . . . it wd/ be well to modernize / cease the interuterine mode of life/ come forth by day etc. (Ahearn 157-58)

^

In the imperial system of Pound’s language, Zukofsky’s function while he is under the command of this rescript is to be absorbed by the newly expanded grammar of the second-person pronoun. On May 6, Zukofsky is ‘you’ in the singular, but by May 7 he is addressed in the ‘you people’ plural of anthropological inquiry. (As in, ‘No, but really: why did you people kill Christ?’) But the rules of the grammar applied to Pound as well. On May 6, they permitted him to realize that Zukofsky wasn’t a banker; by May 7, they prevented him from realizing that Zukofsky wasn’t a rabbi. Pound’s passage from his ‘but still’ to his ‘etc.’ shows us the second stage of the startle reflex: the retreat from the new into preexisting modes of perception.

^

The drive in that stage is toward a reestablishment of emotional homeostasis, and it typically operates by assimilating the new phenomenon to a category, as if it could be understood as an instance of something already known. The term ‘etc.’ subsumes Louis Zukofsky, minor young poet not much respected by Pound, into the magisterial generalization of canto 35, also published in 1934:

^

this is Mitteleuropa

and Tsievitz

has explained to me the warmth of affections,

the intramural, the almost intravaginal warmth of

hebrew affections, in the family, and nearly everything else....

^

Tsievitz, says Terrell’s Companion to ‘The Cantos’ of Ezra Pound, has not been identified, but the missing attribution doesn’t matter here, for Tsievitz or for Zukofsky. What does matter is that Pound feels himself to be in possession of an authoritative formulation capable of explaining Zukofsky to Zukofsky. Thanks to that, Zukofsky is no longer startling. He is no longer what Peirce would call an index; he has been bound into a folio of the history from which new indexical functions, such as The Cantos, are charged with startling us.

6

^

The end of Ezra Pound’s imprisonment was quiet and anticlimactic. On April 18, 1958, the same judge who had committed him to St. Elizabeths twelve years earlier ruled that Pound was incurably insane but not a danger to himself or others, and released him accordingly to the custody of his wife. However, Pound stayed on at the asylum until May 7. It took him some time to pack, and he wanted to see St. Elizabeths’ dentist and optometrist before he left.

^

During that time, and until he left Washington on June 27, Pound spent most of his nights at the home of a faithful visitor from the St. Elizabeths days, Professor Craig LaDrière of the Catholic University of America (Wilhelm 311-16). Seven years earlier, LaDrière had speculated for The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism about the power of poetry to change the world, and the negative conclusion he drew then wouldn’t have pleased Pound. As LaDrière pointed out, Aristotle claims in the Poetics that ‘There is not the same norm of correctness in the art of poetry as in the art of politics or in any other art.’ However, said LaDrière, ‘Plato never arrived at this distinction; so he remains our greatest example of the constantly recurring fact that often those who begin by valuing art because of its assumed power of revealing reality and truth are forced to dismiss it in the end because upon examination they see that its capacity for such revelation is in fact so limited, and its value when judged by such a standard so disappointingly slight’ (33-34). Pound, now certified harmless, couldn’t have liked thinking about that.

^

After all, memory had already betrayed him to the dark forces of a history which remained outside the laws of art. On January 23, 1946, in St. Elizabeths, the psychiatric resident Dr. Kavka had questioned Pound about things not conventionally spoken of, and this was how the conversation ended.

^

JK: Can you tell me something of your sexual history? Have you ever had a venereal disease?

EP: I never had gonorrhea or syphilis. I was married in 1914 to Dorothy Shakespear. She was the daughter of a most respectable solicitor . . . an Anglo-Indian family. My son is Dorothy’s son. Mary Rudge . . . [obviously upset and reluctant to go on]. Homosexuals — you scare ‘em. They can fuck. . . . The trouble with Jews is their basic works. The Talmud and the Bible are anthologies. Moses was the last program. My Zionist program — Zion shall be redeemed with justice. [Communication having deteriorated, I concluded the interview.] (Kavka 159)

^

Pound, of course, was the poet who opened The Cantos (‘a poem including history’) with a historiographic demonstration, rendering the prophetic episode from The Odyssey in a Modern English adaptation of Old English alliterative verse. When he chanted his poems for the microphones that would send his voice down the ages to posterity, he drew out his vowels and trilled his r’s like the vatic mythmaker William Butler Yeats, one of whose mistresses had been Dorothy Shakespear’s mother. During the four winters Pound spent with Yeats, 1913-1916, the future history of poetry in English had been changed forever (Longenbach). But now, in 1946, in a room with bars on the windows, the history Pound tried to speak wasn’t working, because a part of what he had to say had to be wordless.

^

Pound’s daughter Mary Rudge was the daughter of Olga Rudge, to whom Pound was not married. The child was reared in semi-secrecy by foster parents. Omar Pound, Dorothy Shakespear Pound’s son, was reared in England by his maternal grandparents, and Humphrey Carpenter states flatly that Pound knew he wasn’t Omar’s father (451). An unhappy and unwritable chronicle underlay the poet’s speech to Dr. Kavka. But when Pound was writing, he seems to have thought of himself and the history of language as more or less the same thing, so in Dr. Kavka’s office he described his sexual history by quoting from a poem he had inscribed for eternity in his tent in the prison camp at Pisa. There he had a Bible to read (Terrell 361), and what it taught him was that he was the suffering servant of scriptural prophecy. He promptly took control of the advent with an archaic participle and an archaic compound preposition out of the King James Version.

^

He is despised and rejected of men; a man of sorrows, and acquainted with grief: and we hid as it were our faces from him; he was despised, and we esteemed him not. (Isaiah 53.3)

4 giants at the 4 corners

three young men at the door

and they digged a ditch round about me

lest the damp gnaw thru my bones

to redeem Zion with justice

sd/ Isaiah. (Canto 74)

^

The last line of the passage continues, ‘Not out on interest said David rex / the prime s.o.b.,’ and this too found an echo in Dr. Kavka’s office, with Pound’s explicative outburst about the Jews and their works. Not knowing literary history, Dr. Kavka was startled. But Pound was only taming the indices that marked his unhappiness by repeating them, making them into startle-proof, anthologizable quotations of themselves.

^

About language acts like that, Wendy Stallard Flory quotes the psychiatric literature, with its diagnostic categories of delusional disorder, grandiose type (‘the conviction of having some great [but unrecognized] insight’) and persecutory type (‘being conspired against . . . [and] obstructed in the pursuit of long-term goals’) (287). One of the theses of Flory’s essay is that these categories weren’t completely formulated during Pound’s time in St. Elizabeths, so the psychiatrists who thought he might have been feigning his symptoms to escape the gallows lacked the training to be startled in the correct, Pound-specific way. But the example of LaDrière’s Plato seems to indicate that dealing with the Pound startle must always have been impossible, even for Pound.

7

^

For his readers’ guidance, however, Pound has left at least an example of what to expect from the startle reflex. Most of Canto 38 is an accumulation of metrical data points about the international circulation of capital in the years before and after the Great War, when the great steel industries of England, Germany, and France prospered by selling armaments to governments on all the sides in any future war. In Italy, however, says Pound, Mussolini undertook the peaceful, productive labor of draining the Pontine Marshes — an idea that had been talked about since Roman times, but never acted on. And in England at the same instant, Pound tells us, Clifford Douglas discovered the source of war and all its waste in a simple mathematical inequality gnawing at the heart of every capitalist economy. The passage is often quoted as a key to Pound’s economic thinking:

^

A factory

has also another aspect, which we call the financial aspect

It gives people the power to buy (wages, dividends

which are power to buy) but it is also the cause of prices

or values, financial, I mean financial values

It pays workers, and pays for material.

What it pays in wages and dividends

stays fluid, as power to buy, and this power is less,

per forza, damn blast your intellex, is less

than the total payments made by the factory

(as wages, dividends AND payments for raw material

bank charges, etcetera)

and all, that is the whole, that is the total

of these is added into the total of prices

caused by that factory, any damn factory

and there is and must be therefore a clog

and the power of purchase can never

(under the present system) catch up with

prices at large,

and the light became so bright and so blindin’

in this layer of paradise

that the mind of man was bewildered.

^

Prosodically speaking, this passage is remarkable only by contrast. Most of its long first part, says Terrell (158), is a quotation from Douglas’s ‘Credit Power and Democracy,’ and after the canto’s first three pages of fragments and cryptic allusions and inconclusive anecdotes, it shines like a beacon of prose and non-fictional hope from a swamp of poetry and despair. But then come three lines of verse to convey us back to a poet’s mind.

^

The poet is not entirely Ezra Pound, of course. As of 1908, the year when Pound sailed for Europe and lost touch with the changing American idiom, dialect humor in the folk-wisdom style of James Russell Lowell’s Biglow Papers was still popular in the United States, and Pound’s apostrophe’d ‘blindin’’ is a word from the Lowell crackerbarrel register that he was to use in his letters for the rest of his life.[1] During the St. Elizabeths years a detour de haut en bas into that now dead language cost him the friendship of Charles Olson.[2] But in Canto 38 its effect is magical.

^

We will learn one reason when we look up Terrell’s note to the passage and discover the reason for the arrangement of its three lines and its mysterious reference to Paradise. As it turns out, we have been reading Pound’s translation of a tercet from the Paradiso, and its masterful image of blinding radiance comes to us from Dante. But the originality in the English version is all Pound’s, and it consists in the fact that it is a translation. Pound has opened himself up to language and become an organ for the transmission of messages from the dead. When T.S. Eliot discussed that general phenomenon in ‘Tradition and the Individual Talent,’ his riverine metaphor carried him close to the terrain of Pound’s mythic geography: ‘The poet must be very conscious of the main current, which does not at all flow invariably through the most distinguished reputations’ (39). But it was left to Pound to divert the mainstream his way by tagging Dante with the index of a cornball apostrophe, and then riding along into the empyrean on the mighty current of European culture. Perhaps God was startled to see him arrive in Paradise after all, and dressed that way too.

Works Cited

Ahearn, Barry, ed. Pound/Zukofsky: Selected Letters of Ezra Pound and Louis Zukofsky. New York: New Directions, 1987.

Aubrey, John. Aubrey’s Brief Lives. Ed. Oliver Lawson Dick. 1949. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1962.

‘Battle of Washington’s Birthday.’ Time March 5, 1945. <http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,797115,00.html>, accessed July 7, 2007.

‘Biographical Note.’ Finding-Aid for the Thomas G. Abernethy Collection.

<http://www.olemiss.edu/depts/general_library/files/archives/collections/guides/ latesthtml/MUM00001.html>, accessed July 7, 2007.

‘Civil Rights.’ Congressional Record 7 June 1957: 8557-59.

Cowley, Malcolm. Exile’s Return: A Literary Odyssey of the 1920s. New York: Viking, 1951.

Eliot, T.S. ‘Tradition and the Individual Talent.’ Selected Prose of T.S. Eliot, ed. Frank Kermode (New York: Harcourt, 1975), 37-44.

‘Exposing a Fabrication.’ Congressional Record 5 August 1958: 16267-68.

Faulkner, William. The Sound and the Fury. 1929. New York: Norton, 1994.

Flory, Wendy Stallard. ‘Pound and Antisemitism.’ The Cambridge Companion to Ezra Pound, ed. Ira B. Nadel (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 284-300.

‘German UFO Chatter.’

<http://www.germanufochatter.com/German-Chatter-Main/index.html>, accessed July 2, 2005.

Gold, Michael. Jews Without Money. New York: Liveright, 1930.

Hall, Donald. Their Ancient Glittering Eyes: Remembering Poets and More Poets. New York: Ticknor & Fields, 1992.

Harkavy, Ward. ‘World Alliance Against Jewish Aggressiveness.’ Online posting, May 11, 1999. H-Antisemitism, <http://h-antisemitism@h-net.msu.edu>. Accessed May 11, 1999.

‘An Interview with Eustace Mullins.’ Radio Free America 28 October 1994. <http://livelinks.com/sumeria/politics/eustace.html>. Accessed January 31, 1998.

‘John Rankin.’ <http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/USARankinJ.htm>, accessed July 7, 2007.

Kavka, Jerome. ‘Ezra Pound’s Personal History: A Transcript, 1946.’ Paideuma 30 (1991): 143-85.

LaDrière, Craig. ‘The Problem of Plato’s Ion.’ Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 10 (1951): 26-34.

Lind, Michael. Up from Conservatism: Why the Right is Wrong for America. New York: Free Press, 1996.

Longenbach, James. Stone Cottage: Pound, Yeats, and Modernism. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.

Moore, Marianne. The Selected Letters of Marianne Moore. New York: Knopf, 1997.

Moore, Steven. ‘Sheri Martinelli: A Modernist Muse.’ Gargoyle, no. 41 (1998). <http://www.gargoylemagazine.com/gargoyle/Issues/scanned/issue41/

modern_muse.htm>. Accessed July 3, 1007.

Mullins, Eustace. His Spirit-Tower. [Washington]: Cleaners Press, 1951.

———. Murder by Injection: The Story of the Medical Conspiracy Against America. Staunton, VA: National Council for Medical Research, 1988.

———. Secrets of the Federal Reserve: The London Connection. Staunton, VA: Bankers Research Institute, 1983.

———. A Study of the Federal Reserve. New York: Kasper and Horton, 1951.

———. This Difficult Individual, Ezra Pound. New York: Fleet Publishing Corp., 1961.

Peirce, Charles Sanders. ‘Logic as Semiotic: The Theory of Signs.’ Philosophical Writings of Peirce, ed. Justus Buchler (1940; New York: Dover, 1955), 98-119.

Pound, Ezra. The Cantos. New York: New Directions, 1970.

———. Social Credit: An Impact. London: Stanley Nott, 1935.

———, and Marcella Spann, eds. Confucius to Cummings: An Anthology of Poetry. New York: New Directions, 1964.

Pound, Omar, and Robert Spoo, eds. Ezra and Dorothy Pound: Letters in Captivity, 1945-1946. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Robertson, Pat. The New World Order. Dallas: Word Publishing, 1991.

Seelye, Catherine, ed. Charles Olson & Ezra Pound: An Encounter at St. Elizabeths. New York: Grossman, 1975.

Terrell, Carroll F. A Companion to ‘The Cantos’ of Ezra Pound. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993.

Tryphonopoulos, Demetres, and Leon Surette, eds. ‘I Cease Not to Yowl’: Ezra Pound’s Letters to Olivia Rossetti Agresti. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1998.

Wilhelm, J.J. Ezra Pound: The Tragic Years (1925-1972). University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1994.

Notes

[1] In his verse anthology Confucius to Cummings, compiled between 1957 and 1959 — that is, at the very end of his career — Pound included a dialect poem by a popular bard from the era of 1908, James Whitcomb Riley’s ‘Good-By er Howdy-Do.’ And Donald Hall says of an evening he spent with the aged Pound: ‘That night in Crispi’s [in Rome, in 1960], he spoke of the United States with nostalgia and affection, but he did not speak of a United States I knew at first hand. He spoke of my grandparents’ America. . . . You could hear 1908 in his voice, in that eclectic accent which was Pound’s version of the village eccentric’ (Hall 210).

[2] Recalling his last conversation with Pound, Olson wrote: ‘ . . . we sort of forgot [the guard]. Except when Pound, as always so instantly gracious, was quick to suggest he have a cigarette as I was opening a package to give one to Pound. The guard declined, and with that Pound says, CHAW CUT PLUG. And repeated it, CHAW CUT PLUG. Explaining to the guard he meant that’s the only thing he guessed the guard did. The sudden explosion of Pound’s voice in this phrase was quite total to me. It was the poet making sounds, trying them out to see if they warmed his ear. But it was the fascist, too, as snob, classing the guard. And it was Pound’s old spit at America. Add an ounce of courtesy in it, and you have something like what I mean’ (Seelye 50).

Jonathan Morse, 2007.

Jonathan Morse, Professor of English at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, writes about two kinds of language: modernist literature and the poetry of Emily Dickinson. He is also a photographer whose work can be seen at

http://www.saatchi-gallery.co.uk/photographers/index.php?inc=details&id=22826

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/34/morse-pound.shtml