This piece will be appear in December 2007 as a chapter in John Ashbery and You: His Later Books,

by John Emil Vincent, published by the University of Georgia Press.

It is used here with permission. It is about 16 printed pages long.

It is copyright © John Emil Vincent, the University of Georgia Press and Jacket magazine 2007.

1

1

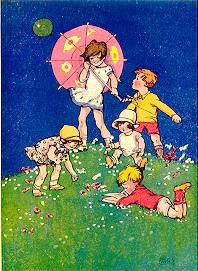

John Ashbery’s 19th book, the 55-page poem, Girls on the run, is less difficult than his recent short lyrics because it is less violent in its syntactic, pronominal and address shifts. This is not to say that it is an easy read. However, the book is literally and figuratively clothed in the lush fabric of the “children’s adventure story.” The cover sports a water color of cartoonish children being blown by a powerful wind, some of them with wings or horns, some carrying what look like huge strawberries, and some being blown clear up and off the panel so that we can just see their bobby socks and shoes. The flap notes that the poem is “loosely based” on the “works of outsider artist Henry Darger, a recluse who toiled for decades on an enormous illustrated novel about the adventures of a plucky band of little girls” called the Vivians. So, before even opening the book, the reader knows that this poem will be in the genre, no matter how tweaked, of the children’s adventure story. Once inside the book, this scaffolding provides a place to lean for the confused reader, even though the narratives, fragmented and skewed, never conglomerate to form a single recognizable example of the genre.

paragraph 2

Critics so far have treated the poem as an exercise in a sort of stream of consciousness, suggesting that the poem doesn’t develop, while it does provide plentiful isolated pleasures. John D’Agata calls the poem: “A toy chest full of options, full of secrets, full of nothing. It’s a diary, a dream, a dump, a dead end” (Boston Rev. Feb/March 2000). D’Agata’s quip echoes, or perhaps borrows from Helen Vendler’s description of Flow Chart, where she calls that book, “...a diary; a monitor screen registering a moving EEG; a thousand and one nights; Penelope’s web unraveling; views from Argus’s hundred eyes; a book of riddles; a ham-radio station; an old trunk full of memories; a rubbish dump....”

3

This tradition of reading Ashbery’s difficult poetry as “toy chest” or as the meandering ponderings of a verbally brilliant poet goes all the way back to the very first critical treatments of his work. He is, according to critics, but in his own words, “a thinker with no final thoughts,” or he is a poet who produces “a steely glitter chasing shadows.” Given this globalizing view of Ashbery’s sense making, that is, that he doesn’t build a poem (or book) with any sense of development but instead follows the thoughts or shadows that take his fancy to the site of their disappearance, one understands why current critics seem much more interested in discussing the relation of this poem to Henry Darger than in discussing the workings of the poem itself.

4

Above and beyond the readerly participation all poems require, “difficult” poems such as Girls on the run require us to construct them as poems. Difficult poetry holds off the desire for epistemic touchdown that contemporary readers and critics often expect, or demand, of poetry. The “sense” that a difficult poem makes can alternate between ur-,super-,meta-,semi-, or non-sense. This oscillation between epistemic registers can have a pleasurable hypnotic effect and it can replace typical narrative or framing devices to create motion or emotion, that is, feelings of departure and arrival, without a story line or sustained ligature of repetition. Simply put, reading Ashbery’s poetry can be like surfing or it can be like drowning, depending. Loathe to either surf or drown, it seems, critics so far have instructed readers to grab whatever might be around that floats and cling to it.

5

And how easy it is to cling to the weird and engrossing figure of Henry Darger. He lived from 1892 to 1972 and in this time never showed his art, the story goes, to anyone; but at his death left a 19 thousand page illustrated epic, entitled “Realms of the Unreal.” Luckily, and in one of those stranger than fiction moments, his landlord was an art dealer and recognized the value of Darger’s work at his death — and so it survived.

6

His writing, according to some, the largest prose narrative ever written, is less interesting, it seems to me, than his painting which depicts panels of what seem to be multiple versions of the Morton Salt, or Coppertone, girl being pursued by battalions of uniformed soldiers, saving naked children from slaughter, hiding from vicious killers in rolled up carpets, &c., and to add to the already riveting imaginative realm of the epic, as it goes along, the girls, often naked, develop tiny penises.

7

The Darger material is appealing; however, any familiarity with Darger’s work and the text of Girls on the run immediately shows how Ashbery borrows very little material from Darger, mostly the idea of “the Vivians,” the “group of plucky girl adventurers,” but not much else. Darger’s work is fascinating but it is misguided to take it as more than the spur of Ashbery’s poem. In a recent interview, when asked what appealed to him about Darger’s saga of the Vivian girls, he replied that he wasn’t sure, though he suspected that it reminded him of the little girls he played with as a child and also of the illustrated children’s books he loved. But Ashbery makes it quite clear that he doesn’t “really like to think of the more gruesome aspects of [Darger’s] work.” These aspects include graphic mass killings, several water color panels depicting an entire field of naked eviscerated children tied to posts with their intestines showing (in detail), mass beheadings featuring severed spines and protruding spinal cords, and scenes of “insane buggery” and multiple stranglings that include vivid eye popping and tongue swelling. About as close as Ashbery gets to the unseemly side of Darger’s work is a passing acknowledgment that “sometimes they [the girls] were in sordid sexual situations” (13).

8

I think that the title’s strange possible polysemy, “GIRLS ON THR RUN // after Henry Darger” is telling: it could be “Girls on the run” (the poem) after Henry Darger, or odder, using the italics for emphasis rather than de-emphasis, Girls (in the poem), on the run after Henry Darger. Darger’s place as inspiration to this poem is unstable, as is Darger’s place as a character in the poem. Just to underline this instability, once, after reading from his poem, Asbhery joked that he wasn’t even sure whether Darger’s last name had a hard or soft g. Ashbery’s Darger has a spectral aspect, he is described at one point as “infinitely dark and creepy,” and his exit reads: “He sat, eating a cheese sandwich, wondering if it would be his last, / fiddled and sank away.” Darger is in the text but he is barely there, just as I suggest his g and his epic are.

9

So, the two common ways to read this book, as “an extended meditation on Darger’s work” or as “aimless” seem inadequate. I’d like, in this essay, to most address the latter misprision, that the book is aimless; I will make the argument that this poem does have a beginning, middle, and end, and a traceable narrative (though this might better be called a meta-narrative). The aim of the book is, as my title suggests, to escape the future, but the author is not himself attempting to escape, instead the drama (of the meta-narrative) is his attempt to help these literary devices we call characters escape their either endlessly repeated or teleologically deadly narrative fates. In other words, this adventure story is about how adventure heroines might escape the adventure story as genre while maintaining their status as viable imaginary beings.

10

Since this poem is large and messy, I want to provide a sense of how the rest of my essay will go: after tracing some of the theoretical stakes I see in Ashbery’s project, I will read the first section for its representation of action in the poem (how it moves), then I will shift to the middle of the poem, where Ashbery uses rampant and often empty naming to produce a sense of “possibility” or “limitlessness” and to vex linearity. Finally, I will discuss how Ashbery exercises this developed sense of “possibility” to lead his characters out of his poem with a reading of the last section, section 21.

2

11

Any time we talk about characters, or subjects, in literature, we are also speaking, implicitly or explicitly, about subjectivity. And conversely, subjectivity is a narrative matter. One term I find useful in talking about the construction of the subject is proleptic retroactivity. This process is looking to the past from the present and devising a path between them. The past thus becomes a product of the future, but also the future is stabilized, fixed, such that it can serve as an end point. That is, we are always defined in time after the fact, we look backward to find the origins of our present. In a kind of paradox: Results produce causes. The past and present are therefore (when this operation is active) always the products of a notion of futurity. This futurity imposes linearity on the story of a life. And futurity, or duration, is no fun. As Ashbery notes in his poem “fun” is “incommensurate / with, let’s say, the concept of duration, which kills, / surely as a serpent hiding behind a stump” (13-14).

12

Proleptic retroactivity, according to Mikkel Borch-Jacobson, and other Lacanians, produces the ego. But psychoanalytic brand-names aside, I find this operation uniquely troubling and helpful when considering queer childhoods. We live in a culture that while it sometimes tolerates certain adult expressions of queerness, is adamant in refusing to consider the positive nature of the reproduction of queer subjects. Of all the parenting guides you can imagine, and they probably, most of them, have been written, one that hasn’t is entitled “How to bring your kids up gay.” I borrow this from Eve Sedgwick. Queer children are created only after their survival into adulthood. The queer kid is not not an ur-subject but is necessarily a peculiarly inchoate subject in a heteronormative culture. Now, this isn’t absolutely different from any child; but it is different enough to merit theoretical attention. There are mechanisms in place not just not to reproduce queer children, but the even more effective and intricate mechanisms meant to make the imagination of any such a lived position impossible. Sure, Heather has two mommies, but does grown up Heather have a twin stroller full of baby dykes?

13

What makes proleptic retroactivity always both central to, and problematic for, any antihomophobic project, is precisely the combination of unimaginability and disarticulatedness that is the hallmark of queer childhood. I will argue that this space of inchoateness, while often dire in its effects on real subjects, is not altogether bad. As Emily Dickinson might say, queer children “dwell in possibility, a finer house than prose.” Queer children have a resistance to tightly clotured subjectivity built-in. But, still, this disarticulated population requires, at least in my account, the operation of proleptic retroactivity to become articulate about its inarticulateness. As you might imagine, becoming articulate, or semi-articulate, about being disarticulated can be a real challenge to mapping a subjectivity in primary colors.

14

Enter John Ashbery. His experiments in Girls on the run, as I will read them, are not only about the relation of adult author to child character, but are also conversely about a hard to conceptualize (except maybe in a difficult poem) attempt to reverse proleptic retroactivity, vexing any futurity to which cause and effect, or clear boundaries of any kind, are axiomatic.

3

15

The first section of the poem begins with the girls already off and running. The initial stanza of the poem seems as if it could be a simple description of a typical panel of a Darger watercolor. “A great plane flew across the sun, / and the girls ran along the ground./ The sun shone on Mr. McPlaster’s face, it was green like an elephant’s”(3). The simple scene and grammar of this stanza are never revisited in the poem. In fact, the second stanza can be read as an attempt of the girls to escape simplicity; here, Judy suggests that the girls ought run because they are about to achieve an audience and that the sort of art of which they are denizens (outsider art) is about to come into fashion. If we read what the girls are running away from in the second stanza as attention which would seek to pin them to a particular aesthetic or fashion, then we can see them as trying to escape stasis.

16

Let’s get out of here, Judy said.

They’re getting closer, I can’t stand it.

But you know, our fashions are in fashion

only briefly, then they go out

and stay that way for a long time. Then they come back in

for a while. Then, in maybe a million years, they go out of fashion

and stay there. (3)

17

Judy is in part making the case that coming into fashion means brief attention followed by anonymity with a momentary return to public favor followed by endless irrelevance. The girls are running from attention, which, Judy suggests, would fix them in a place of honor briefly only to abandon them to desuetude shortly and eternally thereafter. Laure and Tidbit, who are listening to Judy, agree with her but want a tad of optimism thrown into her depressing forecast. They want to add “the proviso that everyone would become fashion / again for a few hours” (3).

18

In the same line as the proviso, Tidbit turns to the author and tells him to “Write it now. . .before they get back.” And Ashbery, presumably, “quivering, took the pen.” The abrupt shift from a simple scene, to a discussion of the vagaries of fashion and its fundamental cruelty, to a command that the author of the present poem write the poem can make sense as a movement. Before attention returns to the Darger paintings in which the Vivian’s have thusfar lived, Tidbit wants the poet to change their venue. If they escape from one type of representation into another they buy time from the impending crisis of being seen. Being seen would freeze the characters in the world where they will be celebrated one day and consigned to a basement drawer the next.

19

As far-fetched as this reading may seem, it is borne out by what follows. The next scene is one of Henry, Henry Darger, being commanded to “drink the beautiful tea” by “the Principal” before Henry “slop[s] sewage over the horizon.” (Henry worked for a long time as a custodian at a school). The Principal is trying to take Henry’s representations of children in hand, as a principal is charged to do with real children. Drinking “the beautiful tea” is offered as an alternative to slopping sewage (presumably grotesqueries and sexual ambivalence) over the horizon of his paintings. The Principal’s distinction between “beauty” and “sewage” suggests that there is a correct and a corrupt way to represent children.

20

Darger’s work stubbornly refuses the beautiful tea outright and his refusal causes, at the end of the second stanza of the poem, the cuteness of “the ice-cream gnomes” to “slurp their last. . . .” A goofy and syrupy sweet fairy tale version of childhood is killed off with the refusal of the tea. The “sewage” or the “sordid sexual situations,” and other unseemliness of lived and imagined childhoods will serve as the stimulant for Henry and Ashbery rather than the predictable and over-prescribed stimulant of beauty-in-innocence. The refusal of both the tea and of the Principal’s principles, lead, in the next stanza, to a build up of energy which is felt only by one character, Dimples. She notes that “something was coming undone.”

21

Again, though the poem doesn’t make this explicit from the very start, it begins to become clear even in this first section, that the girls are running from some unspecified force, perhaps history or fame, but can’t get going without some catastrophe or threat to motor their adventure.

22

Far from the beachfiend’s

howling, their adventure nurses itself back

to something like health. On the fifth day it takes a little blancmange

and stands up, only to fall back into a hammock.

I told you it was coming, cried Dimples, but look out,

Another big one is on the way! (5)

23

While the personified ill adventure is in a state of collapse some new threatening force is on the way to replace it. So again, the girls are set running. It is important to note that whatever is on the way is outside of the Vivian’s adventure story, which lay in a swoon. The unnamed “big one” is chasing them “out” of somewhere. I want to suggest that, considering Tidbit’s command to the poet to “Write it now,” that the Vivians have, in this first section effectively escaped Henry Darger’s art and entered John Ashbery’s. However, this escape, while solving one type of difficulty, launches a whole host of new difficulties.

24

The first section of Girls on the run does quite a bit of work, it gets the Vivian’s out of one representational world into another one. The section starts with a straightforward scene, moves into a discussion of the dangers of being straightforward and attracting attention, shows how the girls’ traditional mode of transport, Darger’s epic adventure story, has failed them, and then shows them escaping their original genre into the unlikely medium of an Ashbery long poem.

25

Once in the Ashbery poem, the question is, what does an adventure character become. This question is in a sense “endlessly deferred” (arguably one feature of fixed meaning in any Ashbery poem) because the group of girls in the poem, this band based on the Vivians, is never exactly defined: Ashbery doesn’t name the members, nor does he suggest how large or small the group is, what constitutes initiation, or their relation to the boys, men, and women in the poem. Interestingly, the nominal elasticity of the eponymous “girls”–we don’t know exactly how many there are — makes them more of a category of character than a group of characters. They are “adventure story heroines” and as such are most of all made up of the will to overcome whatever obstacles they face.

26

In almost every one of the sections of Ashbery’s poem, tapering off at the end, the Vivians run away from some impending disaster: avalanches, floods, explosions, capture, a spill of suds, huge storms, majestic crashes, volcanic eruptions, or, in one particularly egregious case, the lack of a story line. In fact, as heroines in an adventure story, the Vivians can’t exist without impending doom. They are “torn between the impossible alternatives of existing / and saying no to menace” (6). Along these line, the poem asks toward its end “So, what is important, / if the universe decides not to challenge us...?” (42) Crises bring the Vivians to life and make them interesting. And, as with the more typical adventure story, the episodes of difficulty build upon one another into a crescendo, until the greatest crisis, that of not having a crisis, hits in section 18, after which the poem suffers what the last line of this section describes as: “A lull.”

4

27

The poem’s middle sections are quite simply about the difficulty of childhood, both as something to recall and as something to survive. Rarely, something actually happens to the Vivians; most of all, instead, they have the feeling that something is about to happen. They are always about to move out of the episodic (or circular) into the sequential (or linear) but never do. What is childhood, after all, if not the endless cresting of crisis into the quotidian. The child can’t know that if read as a linear narrative, every childhood story ends with the death of a child: Her. No child, that is to say, ever survives childhood.

28

Fairly late in the poem, when the narrative comes to a crisisless standstill, the speaker remarks: “See, they need to have a story line. Sexy. So it appears.” (46). Bereft of drama the Vivians “wait for something coherent to happen” and when it doesn’t “they all [sink] back into relief” (47) Relief, that is, read both as a sense of ease but also as their demotion into a less interesting group, or as I’ve suggested, category.

29

The goal of the adventure hero is to survive (or die trying) and thus her story is one of anticipatory anxiety from the inside and reflexive evasion from the outside. “We aren’t easily intimidated. / And yet we are always frightened, / frightened that this will come to pass / and we all unable to do anything about it, in case it ever does” (9). The “force” that pursues the Vivians is made necessary by their nature as adventure heroines. This force might be understood as adulthood. Their goal in this poem, though they never can know it, is to escape futurity and therefore survive.

30

The poet abets the Vivians in their evasions of adulthood, or of any subjectivity whatever, by introducing new characters constantly without providing them any depth. The poem has far more names than pages. Some recur, others don’t. Most simply exist as the subject of a preposition, or “nervous predicates,” as they are called early on (4). Characters rarely appear more than twice, and never quite long enough for the reader to get a bead on them. Shuffle, Dimples, Laure, Pliable, Tidbit, and Trevor (the dog) are the staple characters, although they never take on much personality beyond that bestowed by their monikers — monikers which make only the slightest gesture to a collective past. Shuffle never seems to shuffle, Dimples is never described as dimply, nor Pliable as pliable, and Tidbit isn’t portrayed as metaphorically bite-sized. Regardless of their vacancy, any scene these staples favor provides the reader simple comfort. Their presence is a sign of the most basic continuity.

31

Some characters, like Persnickity Peggy, are nouns lucky enough to have adjectives, while others like Hopeful or Talkative (with Pliable, borrowed from Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress) are nothing but adjectives cresting into nouns. Some are named after their job, like the seer, the explorer, “Jane’s warlock,” or the witch. Several are on leave from other works of art: along with the above-mentioned Pliable, Hopeful and Talkative, Proust’s Swann has a cameo and Musil’s Young Törless makes an appearance as “Young Topless.” There is a band of “uncles” such as Uncle Margaret, and Uncles Philip, Wilmer and Burt. Finally, however, the most fleshed out characters are complicated by their relation to the text’s production: Ashbery and Darger. Ashbery is present from the first page and becomes an increasingly discrete presence, by the end seeming to be the only living person around in the landscape of his poem. Henry, alternately, after his appearance on the second page steadily evaporates . Several pages into the poem he “fiddle[s] and [sinks] away” (8). Then, near the end of the poem, “He complicate[s] everything by dying” (47).

32

The instability of names in Girls on the run resists the reader’s desire to make the poem into a linear narrative. New people keep popping up. Intriguing inventions, such as Larry Sue, grace but a single passage. The proliferation of names, concurrent with its alienation effect, sponsors, conversely, a comfortable sense of infinite imaginative resources. The poem is large and contains multitudes. One can relax into the fact that there will always be more. There are always crises and always new people to have them, witness them, or cause them. This proliferation is not accidental . At one point the speaker proclaims: “Oh my there were a lot of them / then, some as had names, and these were brought to the front of the group...” (44). At the front of the group as I’ve suggested are Shuffles, Dimples, Pliable, Laure and Tidbit.

33

The poet, at the introduction of the final names in the poem, asks who all these people in his poem are; are they figments of his imagination, figures from his childhood, or some combination of both. Here, he suggests in a kind of dialogue with himself that he has been using excessive naming as a device but finally himself wants to know who all these phantom proper and barely proper nouns really are. “O who were they? / Mary Ann, and Jimmy — no, but who were they?” (54) The repetition of the question cuts through the wistfulness and heightened poetic diction, and grounds the poem in a here and now. These names each might just stand for somebody, but the author himself doesn’t know for whom. Regardless, he wants to make sure that he doesn’t get in the way of the construction and maintenance of a fictional world in which childhood never has to end, to the point of ducking out of the picture. At one point, the poet is scolded by one of his creations: “Don’t stand, I might see you there, she said. Helpless but doomed, // he countered good-humoredly. And these are our intuitions!” (Ibid.)

34

The characters of Girls on the run are the poet’s intuitions and in order to foster their development, he must keep out of their way and even out of their sight. Though they always know he is there, hiding. Interestingly, this offers the fictions agency that trumps the poet’s agency. His wistful final exclamation–and these are our intuitions! — drives home the ambivalence and tenderness of his abdication of authority to his creations.

35

The authorial ability to bring intuitions, hyphotheses, or simply figures to life is ceded to Ashbery’s fictional characters. Fred, the oxymoronically kind and helpful truant officer, who appears suddenly in the fourteenth section, begins to tell the kiddies a fable.

36

Fred chimed in, here’s a diver,

let’s call her Josephine, who dives and dives, further and downward,

all our lives’ span, to the basis of that bridge.

Does that make her any more coquettish than we are? More sure-footed?

No but and here’s what I was going to say

all along, must we recast ourselves in the image of the ocean floor:

To wit, are we not shipshape entities? (35)

37

And the answer to Fred’s quasi-rhetorical question comes a page later when Trevor (Fred’s dog) is complaining that “What I said / no one now remembers,” and the response comes, “Oh, but I do, Josephine said brightly.” Simply, the figure, “The diver named Josephine” Fred invented to explain how pursuing accurate memories of childhood doesn’t necessarily make characters (or authors) any more figuratively or figurally “deep” has come to life in the poem and is now a member of the group. The characters in the poem are as free as their author to invent further characters in order to embody their own “intuitions.” These names are barely peopled, but in this poem, are entitled to introduce further names.

38

In fact, all the characters from the first seventeen sections including the “some who had names” and the “shipshape entities,” deflate into pronouns come the eighteenth section. There is nearly a fifth of the book left when the children are left in “a lull” “waiting for something coherent to happen.” This is where the speaker notes that the characters need the sexiness of a storyline, that they “all sank into relief” and that “everywhere we go is something to eat / and fat disappointment”(47).

5

39

The 19th section, then, begins with the death of Henry and the subsequent abandonment of or stripping of agency from his band of characters. “He complicated everything by dying” the section begins. “Aphasia leaked, / a sprinkle of diamond confetti, over confused lands and places.” The speaker then begins to address a single missing other (presumably Henry) whom he tells: “in your time the fiction we would otherwise be without / stays and stays and finally comes to seem permanent, / all along” (48). At the very end of this section, after Henry’s death, from nowhere, comes the announcement, “the streets absorbed the laughter and lust that had been the morning / as Pamela was at last captured.” Interestingly this is Pamela’s own first and last appearance .

40

The capture itself is only vaguely alluded to in the next, and penultimate, section where, following “a virtual rout,” keeping the word virtual active in both of its registers, the situation is fixed:

41

When it was all over, a sheep emerged from inside the house.

A cheer went up, for it was recognized that these are lousy times

to be living in, yet we do live in them:

We are the case.

And seven times seven ages later it would still be the truth in appearances

festive, eternal, misconstrued. Does anyone still want to play? (49)

42

While this is a complicated passage, it marks the end of activity for the heroines and diminishes their full-fledged albeit solely nominal presence to a single, even if the only, and even if Wittgensteinian — “the world is that which is the case” — case. “We are the case.” This quotation also shows the speaker projecting the truth of the children’s experience into the far off future (where they will still presumably be children) and his own desire to still play which sounds plaintive, as if his own inventions have become serious and no longer want to play kids’ games with him. Instead of playing, the unnamed, unnumbered group of children “danced, and became meaningful to each other. It was cosmic time, / tasting of grit. / If this is a mutual admiration society, / why not?” (49)

43

The children are forthwith taken up in linear time, but then just as abruptly snatched from it.

44

...Time grabs us

again, it’s terrible, for a little while. And then it becomes

more and more like this

in its way. Then time broke off

discussions, they [the girls] were shunted to Sheboygan

[and] some mystery wolf came to the appointment

instead... . (50)

45

Left alone, without the girls, the speaker feels hopeless, in fact, he says, “that’s what ‘hopeless’ / is all about” and he wonders “Who am I to be horsing around?” only to have some other voice counter: “You are someone,” and then the speaker to despair: “Rats.” The conversation here both indicates a desire to become like the children in their subjectless agency and disappointment at being someone, a subject locked in time. An adult separated from his childhood, feeling the verve of childhood perception pass from him and finding his own place in the world fine but uninspiring. “It was just dandy where you were standing. / It was like everywhere. It was just average” (51).

6

46

This brings us to the final section of the poem, section 21, where the meditations on “horsing around” and the meditation on “hopelessness” come to roost. This section starts with a discussion between two characters borrowed from Bunyan: “Hopeful” and “Talkative.” In The Pilgrim’s Progress these two never meet; Ashbery’s characters bear no resemblance to their allegorical predecessors.

47

This section more than any other dwells on the action of memory, what it is, how it works, and how it might serve or desert us. “What is it to imagine something you had forgotten once, is it / inventing, or more of a restoration from ancient mounds that were probably there?” the speaker wonders as if contextualizing this poem’s foray into the children’s adventure story and trying to figure out whether the imagined world he has created is more salvaged or invented — and what is at stake in the difference.

48

Also here the “horsing around” turns into, excuse the pun, a carousel:

49

A horse wanders away

and is abruptly inducted into the carousel,

eyes flying, mane askew. There is no end to the dance,

even death pales in comparison, and at the same time we are forced to

take into account the likelihood of the moment’s behaving badly,

the eventual cost

to our side in terms of dignity, compromised integrity. (52)

50

The horse in all its majesty is “inducted” into the fixity and circularity of the carousel, and sure it is “fun” looking but it is also unending sameness and therefore worse than death. On the other hand, the speaker muses, without fixity, we are forced to the mercy of the passage of moments, moments that might behave badly, ruining us, leaving us in bad shape, maybe even dead. It isn’t clear that linearity with its vagaries from moment to moment would treat us, Ashbery, or the Vivians, any better than the merry go round of episodicity.

51

Linearity, staying off the carousel, offers moments opportunities to do us wrong as well as setting the stage for the infinite deferral of gratification. “So we faced the new day, / like a pilgrim who sees the end of his journey deferred forever. / Who could predict where we would be led, to what / extremes of aloneness?” (53) So a fate worse than death, infinite repetition, or aloneness at its most extreme, at least as bad as death, is the choice. The poet, in this final section, is deciding how to leave his creations, how to be responsible as an inventor of agents that narrative has it out for, one way or another. He does decide finally, as we will see, and his decision is to stay in the landscape but lose sight of his creations. That is, out of sight, they are out of time.

52

The final lines of the poem offer a “somewhere” where narrative interest is always present and therefore characters don’t suffer lulls or evaporate.

53

...then it’s bright in the defining pallor of their day.

Does this clinch anything? We were cautioned once, told not to venture out —

yet I’d offer this much, this leaf, to thee.

Somewhere, darkness churns and answers are riveting,

taking on a fresh look, a twist. A carousel is burning.

The wide avenue smiles. (54-5)

54

There is always freshness and newness to interest the denizens of this new place. And the carousel, or circular time, has been abandoned, in fact, burnt, while linearity, the avenue, is maintained - -but only in its smiling form. And what would it mean for an avenue to smile? Finally, and this is where I will leave the poem entirely, it means, in I think the strongest reading, to curve away out of sight.

55

The road leads further ahead but the author can’t see where, to a darkness that churns with new possibilities. Thus the children don’t have to die with the end of their narrative because their narrative has spawned a landscape, but in order to live in it, they have to be out of sight of their creator whose linguistic production gives them only the either/or of repetition or eventual death. Here, the smile is also the trace of the author who has become, in a reversal of the status of his creations, a subject but not an agent.

56

The way to escape the future is to live unobserved. Like Henry Darger did in a way. To people the part of the imagination that is out of time and then trust, bringing together hopeful and talkative, that language is a “riveting,” “churning,” space, where, creator missing, his limits, time and mortality, are irrelevant. Interest, being riveted, is the point, and not just for a reader, but for the very possibility that there can be a place where fascination never flags. A place where inchoateness doesn’t require a future clarity. In a sense, this poem is itself a machine to produce just such a landscape. A landscape where queer childhood might maintain its integrity as experience but reject narrative.

57

Except only our constructions can live there, we (read, subjects) can’t; in fact, we have to leave for them to live. But leaving them, separating what memory or invention we have of our childhood, changes us as well. For a subject without its “nervous predicates” is neither active nor interactive, and such a subject stretches the very idea of subjectivity which is predicated upon predicates. Can a subject be a subject with no agency? Or can an adult become an adult without having killed a child? Proleptic retroactivity that is refused linear futurity, yet lets the present take hold in the past, seems, like a mirror facing a mirror, to create a mis-en-abyme, an abyss. A place where inchoateness escapes teleology, a place for endless reflection. A place something like this poem.

58

Girls on the run may be a toy chest, in some metaphoric, cosmic sense. But it’s no dream, diary, or dump. And, as I hope I’ve shown in this essay, it is anything but “a dead end.”

Works Cited

Ashbery, John. Girls on the run: a poem. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1999.

D’Agata, John. “Review of Girls on the run: a poem,” Boston Review (February/March 2000), <www.bostonreview.mit.edu>.

Vendler, Helen. Soul Says: On Recent Poetry. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1995.

John Emil Vincent

John Emil Vincent lives in Northampton, MA. He has published poems in Spork, Beloit Poetry Journal, Sonora Review and elsewhere. His critical work includes John Ashbery and You: His Later Books (the University of Georgia Press, 2007) and Queer Lyrics: Difficulty and Closure in American Poetry. He serves as an Associate Editor for The Massachusetts Review.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/34/vincent-girls-ashbery.shtml