This piece is about 30 printed pages long.

It is copyright © Amy Evans, Shamoon Zamir, the Eric Mottram Collection, King’s College London © King’s College London and Duncan texts with the permission of the Jess Trust © the Jess Trust, and Jacket magazine 2007.

^

Eric Mottram was a poet, a teacher and a critic. A figure central to the British poetry revival which began in the late 1960s and a pioneer of American Studies in the United Kingdom, he was an influential editor of The Poetry Review, the journal of the Poetry Society in London, from 1971 to 1977 and wrote widely on British and American literatures and cultures. Mottram’s prolific investigations into innovative poetries and poetics remain ground-breaking; perhaps no-one did more to bring several generations of British readers and students to the excitement of post-World War II American poetry than he did.

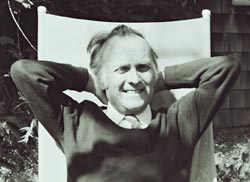

Eric Mottram, Herne Hill, 6 June 1979. Photo © Peterjon Skelt, 1979.

^

Mottram met Robert Duncan in 1968 in London and the two began an intense and wide-ranging correspondence on poetry, politics and the religious in 1971. These letters, along with Mottram’s two substantial essays on Duncan, will appear shortly as The Unruly Garden: Robert Duncan & Eric Mottram, Letters & Essays (Peter Lang: December 2007). While preparing this volume, the present editors uncovered a number of short, unpublished pieces on Duncan in the Eric Mottram Collection at King’s College London. These pieces vary in form, from brief fragments of ‘open field’ compositions to extended notes and lecture outlines.

^

Among the extracts presented here are Mottram’s notes on three unpublished lectures which Duncan presented as ‘Pound, Eliot and HD: The Cult of the Gods in American Poetry’ at Kent State University in 1972. These notes are responses and engagements rather than transcriptions and derived from listening to the lectures on tape. They are followed by two letters to the British poet and painter Allen Fisher which explore the intersections of prophecy and the priestly in poetry — a concern in Duncan’s lectures and a major focus in the Duncan-Mottram correspondence. We have also included excerpts from the letters of both Mottram and Duncan.

^

For Mottram, Duncan was one of the masters of poetry in the twentieth century who stood in the company of Pound and Olson, and the extensive and rich nature of the materials relating to Duncan in the Mottram Collection is a testimony to a remarkable and sustained poetic engagement.[1]

Robert Duncan, San Francisco, 1985, photo john Tranter

^

Square brackets indicate insertions by the editors. Duncan’s practice of moving between square and curved brackets in his letters has been standardized for the present publication and curved brackets used. Some of the originals transcribed here are handwritten. Mottram uses a calligraphic pen and his small script sometimes presents a challenge to the reader. A question mark after a word indicates a cautious decipherment on our part. Obviously unintentional errors in spelling or typing have been silently corrected; some indents at the start of paragraphs have been standardised. The Mottram texts are printed with the permission of the Eric Mottram Collection, King’s College London © King’s College London and Duncan texts with the permission of the Jess Trust © the Jess Trust.

^

Duncan- out of present into eternal presence

to find a language for this via Projective Verse

(necessities of the Maps essay)

poem- “area of composition” -preface to Bending the Bow

sound + rhythm = formation / field

within commune of poetry “the great story he knows will never be completed

(Heidegger)

science - “the universe is faithful to itself” - rationale of composition

“polysemous” parts of the poem–each part is generative of meaning

“mobile” image for “interchange of roles”

“every feature of the poem redistributes” events in time

e.g. The Vietnam war–need to commit the war in person to redeem the

de-natured Americans’ image of the Vietnamese

Uprising

Heraclitus–bios and bow–the same in language

one is life/ one kills

Odysseus–end of Homer- bow/lyre

The Multiversity–pressure of events which cannot be entirely transcended by the

poetic action

“tracing roots and branches” - the monarch butterflies–shared - “almost restore”–

tree of life

Epilogos–desire for transcendence

^

Man’s Fulfillment in Order and Strife — April-November 1968

Caterpillar 8/9 — NY 1969 —

^

Opens with: “ ‘War is both King of all and Father of all’, Heraclitus says.” And then RD claims that different orders of poetry are at war — which is not, of course entirely so.

^

229 — “Every order of poetry finds itself, defines itself, in strife with the other orders. A new order is a contention in the heart or existing orders.” These “involve often incompatible ideas of what world and order are.” “Each of us must be at strife with our own conviction on behalf of the multiplicity of convictions at work in poetry in order to give ourselves over to the art, to come to the idea of what the world of worlds or the order of orders might be. We must go beyond the sincere into the fiction whose authors, Blake tells us, are in Eternity. We must set up in the midst of the truth of What Is, the truth of what we imagine.”

^

— This urge towards a fiction of an eternal universal if itself, therefore, part of the strife for order, for war. War, the OED reports is “hostile contention by means of armed force, carried on between nations, states, or rulers, or between parties in the same nation or state...”. Figuratively, this meaning is carried over into “any kind of active hostility or contention between living beings, or of conflict between opposing forces or principles.” Then there is a further destructiveness: “fighting as a department of eternity”, as a profession, or “as an art”. War is not, then, a quarrel or a dispute: it infers arms which infer death. Why does Duncan believe it to be as permanent and necessary as Heraclitus does? Even used metaphorically, “war” cannot be relieved of its fight-to-the-death-with-killing-weapons inferences. “Laws and definitions” are “replaced”. “The contenders and outlaws” carry “the inner battles of the individual poet’s soul” into “the public field”, and it is a battle to “exterminate the enemy”, the established, which has to “fight...for his life”. This appears to be a vision of the Golden Bow [sic] process, rather than the Bloom process of initiation and variation. Duncan extends “life” to mean here “the very life of our art”. “Disordering” is “creative strife”. A part breaks up, is broken up, “in order to come into alien orders, marches upon a larger order”.

^

The violence [and] militarism of this existential language, (it resembles that of “avant garde” and so forth) is adapted by RD for his own consciously adopted career, a career, which unlike architecture, could never produce the complete. Vitality depended on endless dialectic without rest in a life-order and — forms of process in art which participated in the large process of life, presumably biologically and zoologically defined, without upward with Man as summit.[2] Process is contemporaneous throughout; all survival is without sentimental upward goal. But, too, does not progress or regress in “vitality” — and RD with Pound in The Spirit of Romance: “all ages as contemporaneous”. So that value is not predicated on any one stage as status, or “our contemporary concern with World Order” in “apocalyptic times” is part of “the condition of man”: end is beginning is end ad infinitum. Presumably, nuclear warfare is part of this necessity of process. (Lewis Mumford’s The Condition of Man may be involved here: “To achieve a dynamic equilibrium in every department of life has war become a usual obligation and a test of political sagacity. ...If mankind should succeed in overcoming the forces of disintegration, it will be because millions of men and women, all over the planet, have been at last moved by the tragic experience and the dire prospects, of our time to change their minds and alter their conduct, so as to ensure their regeneration and renewal of our common life” — (p. 81 [sic] — the 1962 edition’s introduction — Secker and Warburg, London]. This hope does not arise from war but “a new form of life-play” ( - p. 4) — when [?] technology is not dominated either by war or rigid conditioning — it moves towards the purpose of effecting “within organism a dynamic equilibrium and to enable it to continue the processes of growth and to postpone those that make for death.” (5). The essential quality of “self-transcendence” does not automatically infer war (7); “Man’s purposes are not alone given in nature, but superimposed on nature through his social heritage: man’s ecologic partnership with the earth and all other living forms must...be complimented by man’s special creations, art, culture, and polity, the processes through which he has made over every aspect of his natural environment, turning love-calls into music and stone quarries into cities” (7-8). War, therefore, is regression into nature and a historical matter which can be transcended. Mumford criticizes Marx and Engels precisely for their allegiance to war as “the wicked passions of man — greed and lust for power — which, since the emergence of class antagonisms, serve as the levers of historical development” (334). Capitalism’s basis in private profit likewise infers war: “On capitalist terms, there is no satisfactory ‘moral equivalent of war’. That was the illusion of the new capitalism: an illusion that should have been buried forever by the calamitous depression that started in 1929” (398). Physical struggle and hardship as not necessarily warfare. Spenglerian respect for physical force has “no place for the very class he represented: the priest, the artist, the intellectual, the scientist, the maker and conserver of ideas and ideal patterns were not operative agents” (374). Spengler’s Saga of Barbarism justifies warfare from nature. Mumford concludes that “the democratic peoples cannot conquer their fascist enemies until they have conquered in their own hearts and minds this underlying barbarism that unites them with their foes.” America’s “passive barbarism”, with its triumph of machinery and arms, “will but hasten the downfall of the Western World”(375-6).)

^

RD agrees with Mumford’s last point: “By the time of the Second World War I saw the reality of Hitler America was fighting as lying in what America was becoming. ...Butchering Germans and Japanese had not exterminated the will top power through terror but extended it.” Macbeth — who is the existence of eternal evil in “Passages 30” (Bending the Bow, ND,1968) — is not an enemy but an evidence of “what humanity can be”. So Hitler: not to be defeated but “acknowledged and understood”. One wonders what the marquis, the concentration camp visitors, the people of Stalingrad and the families of the bombed city dead in Britain would say to that; and how to place Hannah Arendt’s historical diagnosis of fascism’s aims in The Burden of Our Time,[3] within such a belief ([parenthesis with large space left blank]). Duncan’s Macbeth is the epitome of what Hofstadter calls “the paranoid style” of American politics — how in the assassin’s mind/ the world is filld with enemies” — and the embodiment of the state of the nation: “in which the nation’s secreted/ sum of evil is betrayd”. Since “order is disordering”, Hitler must be allowed, even in defeat.

^

Like Eliot, Duncan is fascinated by the ideal in Christendom, it’s medieval Roman Catholic bases, its Aquinian synthesis [?] of Greek and Hebrew, its Dantean force as an example of ideas in action — De Monarchia (Shakespeare didn’t object to monarchy, only usurpers and its Muslim belief in “angelic power” as the figure of Active Intellect (which also fascinated Olson: both he and RD use Henri Corbin’s Avicenna and the Visionary Recital). Dante — as for Carlyle, Eliot, so for Duncan — is the ideal poet because he is the vates, the visionary or prophetic poet, of World Order as God’s art — nature forms the human race in a totally functional whole, a purposeful teleology. Duncan fuses Darwinism into this totality: Creation as evolution by elimination of some of nature for other parts — “the process of the survival and perishing of potential functions”, the very image of natural war. So the World Order’s art is divine [word unclear] warfare. Like Pound in Guide to Kulchur, Duncan is drawn to totality and universals, to presence of arche and telos — and to justificatory human behaviour within the assured actions of the whole, the World Order (with shaky eliminations of mutual aid, love and cooperation).

^

. . .Am I alone in being heartily sickened by Thoreauvian anti-city ecological tribalisms masquerading as priestly poetry which is good-for-you? The Whole Earth Catalogue

is one load of middleclass monied [sic] snobbery to my mind. Detroit workers and Mississippi Delta workers have other situations. And the kids at Kent State — I worked with a range of students from the first three years of their college life, and they don’t want to live in tribes. I attacked Joseph Campbell when he talked to the English department at Kent for his tribalism and maintenance of conflict structures just because they happen to have happened in the past in other societies and been registered in myths for interpreters. The past has been wrong, history a disaster, in so far as the sacrifice of millions of human beings to dogma and structure. Descent into the kiva to be reintegrated into the perpetuities of tribe — that static abomination — I think of the restrictions of aborigines in Totem and Taboo for instance. The tribal contracts. The city is society — we have to invent it. Multiple environments for choice and non-passive action: Thoreau couldn’t even live with his brother. Stroking fish in the middle of the lake on another man’s land only led him to a Samuel Smiles (self-help) attitude towards his neighbour Baker, the poor fishing man, and a belated patronage of John Brown. In America since the first sit-in in N.C. Greenville in the winter of 1960, ten years of failure to change the ownership of the means of production — the grim playboys of the Yippies — the repetitions of the New Left and the separatisms of the Karengists. Presumably Mr Dupong [sic] laughs daily to the bank. The biggest shock to the students I taught in the Experimental Programmes Division at Kent was to discover that Law is political through and through, that there is no ultimate tribunal of judicial protection of any kind for a person in America. [...] And none of the students in that class were taking literature. And all Campbell could do when I said that even if the past was the conflict myth pattern he alleged, it would still be wrong and we would still have to not repeat it, was that when I was as old as he was I’d understand the inevitability...Well, I didn’t think I was that young and daft! Foucault teaches admirably that the return of the Same is what we release ourselves from, and the archaeology of human sciences is not to promote tribalism.

^

O.K. Your voicing your disappointment in ‘ten years of failure to change the ownership of the means of production’ comes to set my own critical apparatus to work. Defeated action may be discouraging — and the defeat of ‘the ownership of production by the producers’ would be understandable enuf in the present scene. But only the worker can seize the means and purpose of his work — and what is defeated at this point is the root idea — he ain’t got it. The guy working in the U.S. is aiming not at the means of production but at the share of the profits.

^

And the ‘revolutionaries’ ain’t workers. None of them are in any line they mean to take over that has to do with industrial technology. Period. What I read in your dislike of the Thoreau — Kiva — (and Olson’s back to the Paleolithic, I take it too) — retreat from any complex knowledge and involvement in what is going on is what I read in your opening remark about the ignorance and laziness of much (sadly of such a large

MOST) poems received in editing a magazine[.] Not only primitivism but modernism (sophistication of style in the place of form) represents a retreat from the problems of actual works. The writer is as much involved in his own field with the critical expansion of technologies (actual knowledge about the workings of language since — to my own knowledge — Freud in The Psychopathology of Daily Life (1901), Saussure (1915), Sapir (1921), Piaget’s Language and Thought of the Child, Kohler’s Place of Value in a World of Facts (1938), Whorf’s work in the 1930s and Wiener’s Cybernetics which was what moved me into action at the point of The Venice Poem in 1948 (i.e. struck me and made for a demand for an other poetics coming out of that poem. The Venice Poem was for me not an achievement but a proposition.) And Cassirer opend up, I think, a social critique of language). These are what set one writer now in his fifties about his work. And there are rumors, I gather from ‘the young’ that there is much more to know about this here business of, industry of, language.

^

Taking over the means of production involves taking over the meanings of production. What comes into it here is acknowledgment of what one does know as well as of what one has got to know. Ignorance from lack of knowledge is not evil, but ignorance from refusal of knowledge is surely evil. Macrobiotic cooking that must finally set up an iron-age curtain against what it suspects to be nutritional facts. An

easy target! since it’s cooking that don’t even taste good. But ‘gourmet’ cooking can also not want to know what is going on. There are no pure possibilities in any art. ART that undertakes what we would admire in the difference between art and just doin’ what comes natcherly is defined by an awareness of necessity (acknowledgment of facts) and of desire (knowledge in process), what you call risk i.e. work that takes

place at the margin of testing, the pragmatic ‘truth and error’ — what I read Charles Olson as meaning by ‘projective’ (tho Olson reads that word not only thru Köhler lenses but thru Jungian contact-lenses and a good deal of willing miopia [sic] along that-a-there line).

^

I guess what I press toward is that the contribution of Olson’s thought for me was to reinforce the conviction that making is not a thing or activity in itself (as often it appears in the Poundian aesthetic) but is doing. The poem don’t get to be an object (any more than a Brancusi sculpture gets to be a universe in itself) — there it sits an act, an actual thing, res in a reality, a factor in a process going on, ‘influencing’, making around itself environment. What then gets to be given? If any thing or idea could be a donée then we could refuse it. Without losing reality. But every thing, idea, once there is information.

^

It’s not a question of ‘risk’ — it’s a risk to lie on your back and stare at the ceiling: ‘back’, ‘stare’ and ‘ceiling’ immediately overwhelm or don’t ‘lie’ and ‘your.’ It’s not any risk that is the fulcrum for me, but the charge of What is ‘in the risk’, of the issue, the sense that something is at work there. And I go to it then to deliver the works, to articulate the factors at work.

^

We’ve gone a long way round, but my thought is back now at the societal works (what — and here I am thinking of Olson’s trouble with the idea of history and his anger at ‘sociology’ — I read in your ‘the past has been wrong, history a disaster’). Our ‘story’ is also not given but we tell it. Your ‘the city is society — we have to invent it’ is exactly my sense. How we live what we do does invent it. The art or poetry (awareness in extention of what and why in MAKING it) is when conscious intent

enters fully along lines of knowledge and — imagination, the architect’s projection of the plans. And that (as any novelist, poet or painter knows) does involve earth and sky. A building which includes an awareness of the cosmos at least at the [...] popular level account of where and what we are, is immensely more informed than one that re-hearses (just noticed the HEARSE in that word) the iconography of a universe in which MAN (and not the subatomic particles was the macrocosm).

^

The weight right now for me is the project of tackling Denise Levertov’s new book with the shaky hope of arriving at some definitions, propositions and structural information worth or justifying an essay at this point on her tangling with what she sees as ‘the Revolution’ (which looks very much like the craving for ‘happenings’ moralized).[3a] Must re-read that storming of the Bastille. The French Revolution almost a model of PROTEST reaction.

^

I once tried to make clear to Denise that any meaningful action regarding the war would have to take place 1) within the army, taking the army over, not protesting against it and 2) within the industries producing war-goods. That only soldiers and workers in factories could actually oppose the war. Without that, action was as futile as the machine wrecking of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. And protesting an idea don’t take over the means of that production either; only imagination — the production of ideas, i.e. images of ‘action’, of ‘society’, ‘love’, ‘hate’, ‘Mother’ and ‘gardenias’ — can bring any new idea into action.

^

Creative (productive) imagination has its event in language. The construct (and here I take the structure we call ‘society’ to be a ‘language’) is the medium of idea. Being ‘in tune’, ‘out of tune’, having ‘counter-point’ etc. all are sensations of construct. We construe in imagining. So, opening new compositional ways, music frees social as

well as poetc ideas. To the extent that we construe the events of our lives into ‘language’ we begin to have a ‘story’ or a ‘field’ of person or self or creativity or in-vention. Every individualized invention is a threat to tribal consciousness — within which each must be a member of the tribe. A politicized member of a polis — what Plato wanted his philosopher to be, is in that sense but moved to a larger tribe. Co-operation and coexistence in a pluralistic field is something else.

^

A Thoreau lives as a member of himself — a one-man tribe. In every act committed to his aboriginal resolve.

[...]

Yesterday I went up to Sonoma State [...] to hear Snyder. And, in closing, would note that tho he presents himself as the verification of the poetry; and clearly to himself takes it the poetry is verified by the Buddhism it presents (as one might take Maximus to be verified by the history or geography or spiritual ecology it presents: or Jesus-Mary-and Joseph save us, Duncan verified by the theosophy or myth or hristianity!) — there is still plenty of reality having its reality because it belongs to the poem — tho he think it because it belongs to the subject of Snyder’s ascendancy or shamanbeing or whatever.

^

Motto for the month: to put the SHAM as well as the man back into shaman.

^

Or else the Pacific Gas and Electric having all that power must really be something!

Robert

^

‘The meanings of production’ — OK: this is what I meant about reading Reich, earlier. Production must mean what the body produces and takes in and gives. The horror of stabilized entrapped family sociality is the alternative to labour which most people have — i.e. in London at the moment a fine production of O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey at the National, and a film about a girl’s schizophrenia brought on by the family stratifications (out of Laing and Cooper, probably) — Ken Loach’s Family Life: if this gets a wide showing it will do something towards understanding production meanings. (Loach made Kes, incidentally). The family producing what most people have of life when labour is finished. That is, appalling relationships of compensatory competition. And still the George Steiners of this world go on abstracting — I was reading the Theses on Feuerbach the other night, in connection with Caudwell, and thought how that last one still isn’t used. It’s the model of what is possible that the workers lack by education. What their productive life could mean — life as an Olson projection, to use your insertion here: transference of energy. Aesthetics and majority life must be discussed in similar terms if they are to have validity. How much did Olson know of that? There was so much I wanted to ask him and yet I never even saw him in his life — partly my own fault, since when he was in London I was put off by the circle of sycophants which called him Charles and bled him: they invent nothing, let alone the city. They — precisely in your sense — re-hearse: in my sense, repeat tyrannously. Only plants and animals have the right or necessity to repeat without deathliness. Denise Levertov is in danger of alibi work — getting into actions which give viable experiences of accurate suffering. No risk there: and the sense of interface instead of form. Better is how the Army responded to Bob Hope at Long Binh, Christmas Day 1971: ‘PEACE NOT HOPE’ and ‘WE’RE FONDA, HOPE’ (how about that comma?) And a soldier saying ‘I don’t see shit for TV shit’ as Hope read his boards of jokes and the cameras got in the man’s way. All his female lib and pot jokes failing. His homosexual innuendos falling like dead shit in the atmosphere of revolt. The finest protest meeting for years. That’s what I read into your criticism of Denise Levertov — the meaningful action taking place within the Army. They knew why visas had been refused the Fonda group. But still, the unions, as Ferlighetti says [...], support the loading and manufacture of war goods — those terrible lines of war goods in trains in Allen’s Wichita Vortex Sutra. One reason I value Tom Pickard’s friendship is his clear inheritance of the better ranges inside what it means to be Newcastle (mines and shipyards) working class: if my poems and prose don’t get into him, I’d feel hopeless, since he knows literature from personal need, not any kind of schooling. That is what your ‘opening new compositional ways’ means to me. Plus where Everson sees poetry as still having a complementary purpose to rock music [...]. I just suspect Plato’s politicization of the polis because of that code of trained guardians in a hierarchy of jobs: can that polis sense be tribalized without mythicization? Tribe is closed society of inheritances is it not? How to develop potentials in that set-up... [Mottram’s ellipsis]

^

And as your description of merrie England brings it home, every protest against the triumph of the corporate state here in the U.S. is fulsomely verified. Rexroth has been writing some beautiful pieces in his column for the San Francisco magazine. I.F. Stone in a recent interview done for N.E.T. put the shot — that the intellectual task still unrealized is to formulate a socialism in which the freedom of the individual will be kept as the paramount social value.

^

I’ld [sic] pick up right there and stress that it is in the order of the evolution of species and ideas — Darwinian, not Lamarckian — that the principle of variability, of ‘error’, must be kept alive. Rewrite Marx’s ‘From each according to his ability’ — as Vanzetti did, to read: ‘From each according to his volition’ — not because it represents some sentiment of individual rights but:

^

1) Creativity comes not from what one can do, not with any guarantee that one will be able to do, but from the will to strive in the area of unknown possibility (i.e. with certainly a likelihood of error). In our present crisis (but this is, as I see it, the condition of any presentness) we must do what we are not able to do. The ‘ability’ is yet to be created. And all known abilities seem to go drab; except as we go beyond them.

^

2) ‘From each according to his ability’ is a requisition that will be made by any committee of bureaucrats, following aptitude tests, etc. But ‘volition’ can come only from the man’s nature. It cannot be requisitiond or coerced. Comrade-feeling, friendship, love are voluntary; workmanship is voluntary;

● [sic]

^

And ‘to each according to his needs’ is to be read as ‘to each according to his wish’. Again, to return the individual to his having to learn his nature (face the facts of what he wishes) — in which ‘need’ is radicalized to come to its crisis in the individual wish. The committee or the friendly social worker will prescribe what one needs, but only in the coming to the inner truth can the individual find that wish. And the wish again has that all-important lack of guarantee, the variability in which entirely new values enter potentially — and hence again the quality of error (‘I did not want what I wisht’).

^

It is in the will and the wish of the individual that the society comes to crisis. Writ large, in disorder, the monsters of politics who express wilfully and wishfully their ‘message’ with the manipulation of human lives, elemental resources, express whole societies. Hitler expresses Germany in an expressionist period. Johnson and Nixon express at every turn the U.S.A. But to read that right, your insistence on the meaning of class (as the relation of the individual to the production of life possibilities) shld. move that word ‘society’ out of our way. Whatever ‘society’ Nixon belongs to, it ain’t mine. But he as much as I has got to eat, keep a shirt against the cold wind, a roof against the rain.

^

(RD’s aim is to show the invocation of the gods at the crises of three related poets, and through this the reinstauration of the gods after their disposal as irrelevant, disreputable and silly by the rationalists, the Catholics and the Mencken booboisie — mentioned specifically)

^

I. October 11. “A tale told of the imagination” — “the masters everywhere present in my mind when I’m writing a poem” and “in my experience”. He has read them since the middle 1940s repeatedly, and TSE and EP since he was 16 or 17, and HD especially since the publication in the middle of WW2 of her work in Life and Letters Today. The proposition: logos is a person of God. This was the centre of the conference with young theologians to which RD and Denise Levertov were invited, at a time when the demythologization of religion was a major topic.[4] Levertov spoke of her calling Apollo to witness at Delphi her dedication to poetry; the testimony of her vow to poetry — a power, a person, a thing called Poetry. RD quoted her account of the occasion (c.f. Henry Miller in The Colossus of Maroussi): in the special place and with “the god presence...I felt there certain dangerous favours”; and a change did take place; the prayer was listened to; something Dionysian, the continuity in different names and at different times, of the same gods — “I prayed for certain favours” — not to Apollo, as the theologians mistook, not understanding the event. For RD this is the example of the experience of poetry as a power, as a divine person in other historical accounts, for example, in Plotinus — that which dominates the imagination of Yeats and Pound. Levertov is the daughter of an eminent rabbi who became converted to Roman Catholicism: his theology is written in Hebrew to the Jews, on Christ: the centre of the idea of the conversion of the Jews, and for Duncan an example of what earlier is considered as a pollution of ideology or denomination. It is, in fact, the deeply polluted, mixed waters of Christianity and Judaism which is precisely what is recovered. The tradition is strong enough — it is Milton’s concern, for example. Christ had become unreal in the USA and Britain by the Thirties: it is both this unusable area and the actual tradition that these three poets inherit. In the London of Pound, Eliot and later HD, the presence of a minority going through history and returning with the religious inheritance, which is re-named into the identity of America. A return to the stream of dangerous favours. In the USA Mme. Blavatsky, a hashish chain-smoker — using the N. African variety — the disreputable version of the tradition, but still part of the mixed bringing together of what had been academically separated (it was Americans invented the word cubism). “Pot and pantheism” is one way of it — (and still rife) — Yeats moved out of Blavatsky towards the gods of “pot and pantheism” as actually practised, positing godhead again and the major powers given — logos, light, Christ — ransacked Hellenism and the Renaissance (as the Renaissance had used the classical) and recharged what was the task there. Yeats loved Pound’s poem “The Return” — that is, of the gods — because it had “got it where he wanted it”.

^

Canto 1: blood for the dead to be called up again, the bringing forward of the dead spirits to us. The gods are the world — the seasons, the Earth, etc.: it was a reviving of meaning: e.g. Helios is the god of the Sun and therefore is the Sun, since the sun has always been there: the meaning of myth — the practice of the gods as we get a hint of it in the poets who practice it, and those who tell about it — Duncan’s own family were part of the tradition in their own way, which was not as literary and for them as ordinary being Baptists.

^

Events into which the mythic flows and into which they practice the gods. In WW2 Duncan was a pacifist, and practised the seasons, and studied colonies and communities of the seasons. He came to understand that God’s love is, in this sense, always present, as the Christians say, overwhelming, not received, “a one-way proposition in which I actually win” (i.e. in the sense of having it all).

^

Eliot in The Waste Land says April is the cruellest month — the passage is the epiphany of what he refused to come to, as involving something fearful, and referring to a sexual encounter refused — the poem called “Narcissus”, also — the figure of Tiresias — and all the presences of the poem drawn into Tiresias’s situation — the experiencing of suffering. It is Eliot’s daily life at the bank and his nymphomaniac wife, work and destitution — “the central part of the poem is a vast realm of his rage” — from his job of wrapping pennies in the bank to the full charging of the situation with the Greek show: madness, terror; the cruellest month — and thence to Frazer and Jessie Weston, the dark wood, the sacred grove — the entrance to the poem, the entrance to the waste land (not the other image, the rose garden).

^

At seventeen, Duncan was “seeking to make real what I was through cabbalistic Christianity and a popular hermeticism” — his parents’ religion (his father was an architect). He had moved into Yeats’ area. It was a highly intellectual passion, “spinning a tale beyond belief”, but he did not want, at the same time, to join anything, whether the Boy Scouts, America, any kind of order with rules. Referring to Levertov at Delphi, he said: “I know I took that vow long ago” — and thus did not need such an assertion. Spicer: suicidal — drinking to death — his extremity of only one point, one redeeming thing — his trying to force life into making him write the poem again. “Forcing his office” — Duncan, on the other hand refusing to be “pushed by poetry, by the poem”: life first. Eliot, also, he says: “he walked away from the poem”.

^

At 14 or 15 he had had his horoscope, palm, etc. laid on him by the family. Until he was 21 — then his decision not to be in the order of religion but the order of poetry: he was already a poet (Yeats was in both orders). He understood it from “The Burial of the Dead” — the rite: to make the dried tubers into growth. The beginnings are there in the 18th. Century — the elements in the gothic novel, refusing rationalism. His own experience of vampire movies. M.R. James: a medievalist, edited gnostic versions of the New Testament; the classic edition of gnostic texts — the sense of energy there as in Weston’s work — folklorist: work on the Grail, whether it was pagan or Christian — she was converted to Christianity. The gnostic matter in the Grail — this got her directed to G.R.S. Mead, and then to the London groups “who practised the Grail”, she says indiscreetly. Eliot wanted to cross out any implication of infection from this material — what RD calls “the Typhoid Mary of the Divine World”, Jessie Weston. “The Typhoid Mary of the Classical World” was Jane Harrison — who in later life learned Russian in order to go to Russia where was still practised the cult of the bear, origin and homeground of the Diana she was looking for.

^

This is the atmosphere of The Waste Land — his essay “Modern Poetry” talks about the poem. “Fire Sermon”: burning rage and madness — it is poetic, passional, in a shy and secretive young man — he is asking if it can be cleared away: a prayer, therefore, for change, a burning away. Duncan relates this to his own Venice Poem: he [sic] re-entry into his own area. Eliot’s poem is not only what the Twenties were like, after the rape of a culture and a language. It is a prayer to a Lord to pluck him out of burning — as in Greek drama: to present and enter such a crisis of real experience, so that the Lord would have to come and take them out of it — not a social-worker therapy, but the going through it.

^

After the age of Tennyson etc., poetry, it was felt by some people, was in need of a tremendous experience. It might be just a scream. Artaud ended up just screaming. Then: a cry for water in The Waste Land, leading to “the third who walks beside you” — man or woman (RD does not speak of homoerotic experience in either Eliot or Spicer.) The prophetic: “violet air”, etc. — Nagasaki was blasted in violet air among the mountains, at a time when most people were there...The day called Project Vatican — the Bomb called The Child — Thomas Merton’s paper on this (Hiroshima). The condition of deprivation: unable to weep (RD refers to the experience of weeping in 17th. century poetry as a condition of the edge of the divine). — “How much it floods into my work continuously” — and through Eliot, the experience of Dante and De Nerval. An event of deprivation and weeping [b]egan to be an event in a drama which gathers together for a prayer for the return of rain.

^

II. October 18: Pound. Crises — times of extremity, where the gods and demonic heroes attend Pound himself. He covers his traces in most of this. His immediate sources were 18th. century — Jesuit sources for Confucius and American politics. Importance of the place of friends in the poem, Yeats paramountly. Pound read to Yeats in the south of France, after he was told by doctors that he was going blind. So that about 1910 Yeats loads on Pound what he was himself attacked for, his disreputable world where Isis, Osiris, etc. were living gods. Which the Kenyon Review and Southern Review writers, Christians and rationalists, found offensive to their pieties. One of the first visitations is Pound’s propositions of scenes of Hell. The opening of the poem itself posits Hell. The Hell is a reality — and Pound has no guide — because, RD believes, he would not initiate a choice of guide: Kung is his ancestral spirit: it is not a matter of chosen tradition. But as in Dante, the heroes have a place in Hell. Dante’s is a coexistence of a spiritual exercise and a trip, into a deep reality of thought and life. Pound, too, is in his poem. Pieties are constantly introduced to support him. Bankers and publishers, the western conspiracy of finance and politics is the material of immediate Hell. (RD’s Hell in Passages). Plotinus at one point as a guide in Hell suddenly named from Yeats-land: a prayer to Helios, blinding sunlight (Yeats blind, as Homer). (RD does not mention EP’s awareness here and throughout of the Eleusinian tradition). RD tells how he had asked his workshop class reading Ciardi’s translation of Dante who they would take as guide to Hell — they replied Ciardi...

^

Being mired in Hell; how to get out. He sees naked Blake howling against the evil — etc. (Blake does not reoccur): image of where Pound is finding himself, in spite of 18th. century and Chinese rationalist life. Pisa and Washington will be his future, his surrender to the US Army forces. Kung is the rationale back of the totalitarian society which he supported and which fell apart. The real threat of execution in the Pisan camp: other prisoners were executed — for theft (as patron saint of poetry is a thief — Hermes) and rape (primal expression of the poet seizing his energies). The poem presents the disposability of men in the American Army context, especially the blacks when guilty of rape... This is our sickness: the prayer to the powers of the gods’ world is the prayer for release. Pound introduces the material of Benin and Frobenius: the City of God as Hoo Fasa — i.e. you have to move to the City of the blacks in the camp. Then a movement to the earliest of the gods in the Cantos, the passage beginning “the moon has a swollen cheek...” — the Kyrie Eleison — burning of leaves — to the gods, incense, etc. — Manitou — Lynx — Kore. Pound identifies with Persephone in Hell and her six pomegranate seeds: she becomes a power in Hell as Pound becomes a power of Hell, repeatedly.

^

Odysseus becomes the Odysseus of Dante, where he is guilty of misleading his men: the one whose [sic] has lost them on his voyage, grand evidence for the Christian Renaissance period that he hero of the pre-Christian world led men astray. The workers and sailors of the world complain: you had Circe and Calypso, but what did we get besides ear-wax and poison? Now magically Pound charges this material with his own fate and some picture of his hubris, the six seeds of an error, of a fire — the pomegranate: “O lynx, keep the edge of my cider” — lynx as guardian leopards of Aphrodite’s cell, and “puma sacred to Hermes” — the form of his goddesses through the poem.

^

Earlier: the lotus-eater, somnolent, mirror-like surfaces, the stillness into which the poet looks and finds the scen[e] of the poem. Now calling forth presence to attend him: prayer for rest rather than illumination. Turbulence and rest is the movement, and the times of rest need prayer. Times of silence, after the troubles he got himself into. Silence is rest and despair, and a turbulence beyond words. Pound’s is the pattern of life which has many returns to itself — in the poem. It is a poem without salvations: it has rests to turbulence, without solutions: it is the poem of our times. It is not Dante’s return to Catholicism, or any other return to salvation, the Anglo-Catholicism in Eliot, for example. In reply to Eliot, Pound said he believed in Kung — that was his election. As RD observes, if you take a centre, you have to eliminate so much and none of us wants to do that: and the poem refuses it. Pound is a reactionary — that is, he reacts; a conservative — he conserves. Later in the Cantos he has a new series of heroes holding the line — Mozart, Linnaeus, Agassiz — from the beginning of the 19th. century, before the decay occurred: heroes of the human feeling for order. A prayer here for coming to the feeling of order. Mussolini had been torn to pieces by the people of Rome (RD presumably means Milan). Is “serenitas” possible? The possibility of Aphrodite, the power woman — Aphrodite Artemesian as a huge crystal: you lift up to that crystal: the poem becomes that crystal: it has that centre.

^

Canto 116: — Aphrodite as crystal light. “a little light/ in great darkness” — the minimal thing which at least in this moment rescues a man from Hell: a pathos. And: “I am not a demi-god, I cannot make it cohere”. He had recogniz[ed] - his saving by plants and animals — which he did not break with, when he broke with everything else. “A little light to leap back in splendour”.

^

III. October 25 — HD

RD’s aunt’s cult, the I Am (?) [EM’s bracket], which uses the Bible, Whitman and Shelley as texts — that is, contrary to a critic he quotes, you do not have to be a student of literary history, have an academic training, etc. London: a psychotic crisis in HD’s life — but not a break in consciousness or experience: we have a record of this continuity. As in Pound the war is experienced differently. HD was criticised in America, most brutally by Randell Jarrell: “HD is silly in the head”. RD goes into the origins of “silly” — salic, the world of cripples, fools and widows, those in the hand of God, and not to be dismissed: where we are informed of God’s action: the 18th. century made these origins into the modern “silly”. Intensely educated, and part of a small group devoted to a higher experience. She broke early with Pound. Her later group is psycho-analytically centred, they have entirely ritualized the nature of psyche, and the politics of WW2. She goes back to imagism and Pound’s sense of tradition — and back to the presence of the gods. She and Lawrence had earlier exchanged Orpheus and Eurydice poems — their mutual distaste for sensuality, and the fever in both cases — in Lawrence tubercular, in HD actual fever. Practice of the gods — in the Freud book: sessions in which they shared the poetic order of Freud and his bringing forth of gods, ikons and emblems — deeply immersed in the entities of the gods in the old world. Behind his consulting room, a back room of treasures — statues of Isis, Artemis, etc. — the gods of the old world — reintroduced into Judaism (which is non-imagistic) — a troubled room of first gods and images, back into the monotheistic 18th. century mind; the unconscious back of the rationalism of monotheism. Freud could help with neurosis, the knowledge of what happens to you; psychosis he repeatedly could not deal with.

^

In HD’s work and life: the virgin which leads to the grand harlot and then to Helen.

^

Listening to the seashell and hearing voices: a practice of ancient poets — the shell and the fireplace, — the images. The appearance of the gods: Amen, Ra, Osiris, etc. — not like Jehovah — and the Christos: this is also Lawrence’s sense of another, un-bourgeois, Christianity in The Man Who Died and The Escaped Cock — a Christ rescued by an Isis — that is, the restoration of the Christos from the centuries of the church’s separation of Christos from the other gods. Christos as Lawrentian man. HD was raised as a Zinzendorfian Moravian: she came to recover what she had rejected there. “Pound throws away Christ because it’s in a junk shop” — the early 19th. century problem for these poets.

^

Tribute to Angels — using a book on practical cabballa [sic], a magic of angelic theurgy in the Jewish world, which by the 17th. century and Boehme had combined with alchemy and been taken over into Christianity — becomes Christian cabbalism — Hermes Trismegistus, etc. War is the immediate alembic she is in: she has been in the bombing, in a house bombed in London — the walls literally shook, etc. She had that in her psyche which Freud knew would develop a psychotic episode, which psychoanalysis could not lift: she saw a hieroglyph appear on the wall written by a hand. Freud knew what a poet was.

^

HD wrote a version of the Ion of Euripides in which one of her own passages contains: “you must know why you strive”. The magic practice of dreams which goes towards knowledge and reverence and not towards manipulating things (dream used by poets and psychoanalysis). In the poem: the tree which comes alive and shows energy in the city lives — prayer for and end to deadness. The wall is blasted, she finds the blasted tree and the flowering in spring. (After The Interpretation of Dreams comes The Psychopathology of Everyday Life). It is an ordinary tree, to be seen everywhere — the possibility of rebirth — what surrealists mean by objective correlative (Breton): the dream figure of consciousness, your own and collective — the City (the larger mind you are living in) — the immediate metaphor: body of the angelic, the embodiment, impersonation. (In Eliot the issue is incarnation: not mentioned here by RD — and his used of objective correlative passed over as obscure to RD). The tree becomes a figure — an angel. The old woman comes to dream of the miraculous child which would have been the child of HD and Pound — he had taken her virginity when she was 15 or so — identified with Goethe’s Euphorion. And there is a reference to Helen in Egypt and other Helen identities preceding it.

^

So who was the figure? is what is needed to know [sic]: the presences, attendant spirits, of each minute — practical magic which produced the figure, the woman — Mary, the Empress, the Goddess, etc., etc. — all the forms we know — the readers have to move the appearances which they share.

^

“The poem which entirely changed the order of my poetry”, “revealing my spirit to me in her poetry” — the appearance of cabbalistic magic of the angels — back to RD’s parents’ religion: the reverence of the parental “passional quest of the divine” — it then looked not absurd and exotic — or “silly” — but through poetry, the presences of the gods — what HD calls “heritage” and “birthright” (the passages read from the poems here extensively)

^

What is the book she carries, the lady in the dream? it [sic] is not “the tome of the ancient wisdom” but “the blank pages of the unwritten volume of the new”, “Psyche the butterfly out of the cocoon” — the book awaits the tale. In the 1950s, those poets RD associates himself with — “we were coming to the place where something was going to happen and that made a ‘we’. We must also be ‘silly’ to believe that if we went over to the poem wholly for this event”. Poetry as part of an old order: what the magi bring, the coming of the child, embodiment of spirit.

^

The Flowering of the Rod — beginning — read here. The women of the Twenties with their appearances, clothes, etc — “their sense of supernatural dress” — the fire and ice (fever) — “for theirs is the hunger of Paradise” — (“it was not a put on” — RD).[5] The urge to resurrection — “simply of affirmation” — the image of the first wild goose, and of happiness in paradise.

^

40 Guernsey Grove

London SE 24

January 31, 1976

Dear Allen,

^

Re Druidics and Poetic Action from a Distance (Necropathia): which are part of the same mania: and we had better throw in Egyptianisms. It is a matter of what “prophetic” may mean, not too ambitiously. Vertical analysis and an understanding out of it that suggests direction — yes — Dante’s direction of the will. But Druids are priests, agents, powermen, coercers, the Establishment, a closed cult for Celts. Action at a Distance is the dream of power: end of Mailer’s An American Dream, everywhere in Pynchon, dreams of power by nutty poets — no more than sticking pins in an effigy? The serious part may be this — and I went a little way into this in the IT article some time ago[6] — fields of energy which a slight alteration in may serve to warp into radical metamorphosis — the basis of the I Ching for instance. But that is not a priestly divinatory system, as far as I know. Gods and devils are action from a distance: and Druids indulged in human sacrifice. Celts were headhunters.

^

Joyce told Stuart Gilbert: that Finnegans Wake included “premonitions of incidents that subsequently took place”. That is he was superstitious and vatic. He needs angelic visionary penetration “from above” (see my book your London Pride is publishing).[7] This seems to be useful provided the angelic vision is relinquished as an instrument once its use is fulfilled — not kept up as a charismatic position of arrogant leadership.

^

Current occultisms and Druidisms and shamanisms are power ploys of poets wanting action at a distance. A hidden politics which smacks of anything but trying to discover what socialism might mean as a beneficial, democratic society. There’s no society in Castaneda at all. O, D, and S[8] are laboratories with white-coated acolytes tending the sacred flame of the sacrificial altar. Poetry of this area is loaded with the dreck or refuse of past ages, old clogging consciousness, round and round, as per Finnegans Wake — and again I had a go at this in the Kent Journals [sic][9] re Brown’s Closing Time, a neat exposure of cyclicisms as conservativism verging into fascism. Magical dreck — all that burden of stuff in Kelly, Grossinger, and other neo-Joyceans: the desire for the all as absolute. It’s that dreadful need in Ahab: he gets the crew to drink a potion of loyalty to his mad hunt of a whale he believes to be the mask of the absolute: “strike through the mask” and you have power — i.e. you can coerce. Prophecy means this to some poets in this o-d-s line. Perhaps they want to be geomancers — or archaic magi — hence the alchemic dreck around: forgetting the [page cuts off here]

^

The dadaists and surrealists in France and Germany were operating counter-power against the bourgeois-fascist state — épater les bourgeois doesn’t necessarily mean having an alternative, democratic philosophy: as we know from our latter-day dadaists in London — and, although I know you disagree, those writers in the Spanner on Fluxus etc...

^

We need to examine the dramaturgy of power in operation in any field. The idea that poetic power is exempt leads directly to o-d-s.

^

^

a. aim: the demystification of power: not Sinclair, Kelly, Grossinger, etc., or o-d-s. Fascisms thrive on the perpetuating of the mystification of power: secret rites, The Balcony, secret societies, occult havens, covens

^

b. aim — to expose the dramaturgy of all power situations — The Authoritarian Character, Mass Psychology of Fascism, maybe Mackenzie’s Power, Violence, Decision — to end, that is, the mystique of agency, of absolute authority — the absolute — and its charisma. Democracy begins with the constant scrutiny of power — “the end of ideology” always means: give permission to power, as if it were not a matter of right and wrong but effect. The aim here is a value-free society, as it is called by the rogues who talk about such things. Understanding is the basis of the democratic, not consensus under power (coercion), or priestly agency — Crowleyism.

^

c. aim: to expose the dangers of information biased towards burdening the public with what seems inevitable, natural, hopeless — to increase the sense of powerlessness, and the power of the information-givers: the consciousness of people is pressed under earthquakes, tidal waves, plagues of rats in far off parts, two-headed twins in Bulawayo, hotel fire in Calcutta, a revolt in Patagonia — and the neglect of analytical information of the local scene: which would suggest not inevitability but what can be done (and not prayers, rites, the dreck of o-d-s.)

^

A. those in need of domination and submission shape decision to manipulation — in poetry as in other forms, of course: no separation between aspects of human action. Manipulation here would be making work for religion, teachability, making it reviewed in TLS, Observer, etc., grant-worthy, publishable by the capitalist publishers, fashion etc. Language becomes jargon, sales talk, dust in your eyes.

^

B. Those in need of constant appreciation and conventionality: as above — it’s a version of Control. Writer becomes agent of Control, god, gods, the Centre, Middle of the Road, Mainstream, History, Party, Life Force, the Devil...writer as addict, in the wide Burroughs sense.

^

C. In what does a writer have confidence? In what way does he wish to be read and heard [?] Recognition patterns (classicism) is the temptation: like making a spell properly drawing the right signs for power to enter, placating the Control Centre — the poet on his knees before a god. Poet as agent of mystification.

^

These are just notes towards: we’d better think seriously about this, since poets we respect somewhat move now towards the refuse of political-religious flunkeyism.

Yours,

Eric

[Date cut off on Mottram’s copy]

40 Guernsey Grove

London SE 24

Dear Allen,

^

A further stage of where we began, January 31. I was thinking we ought to ask if Duncan’s Return of the Gods is possible even as an idea of any value. In his introduction to Radin’s The Trickster, Stanley Diamond quotes a Maori native-court testimony: “Gods do not die” / “You are mistaken...Gods do die unless there are tohungas (priests) to keep them alive”. So is Duncan saying that the Return of the Gods can be promoted without the aid of intervention or agency? Or is the priest-shaman-druid business a necessary way of re-proposing gods? In any case, “gods” needs careful definition if it is not to be authoritarian necessity under priests and kings. Quite apart from whether the believer in the Return is speaking of the return of Deity “out there” or the return of the idea invented by men which is called Deity. The hermeneutics of the thing must be clear from the start here — which is precisely where I find so much hypocrisy in this whole shaman-druid business. It looks to me as if the poets want power at any cost.

^

Out of his Pater-influence[d] scepticism and concern for “the item of ecstasy” (a transfer of Pater’s Renaissance “single sharp impression” and “moment to moment” forces — the ancestor, obviously of Imagism and Olson) Stevens says in “Two or Three Ideas” — 1951 — year of “Projective Verse” (it’s in Opus Postumous, 1959): “All of the noble images of all of the gods have been profound and most of them have been forgotten. To speak of the origin and end of gods is not a light matter. It is to speak of the origin and end of eras of human belief”.

^

“The gods were personae of a peremptory elevation and glory”

^

“In a time that is largely humanistic, in one sense or another, it is for the poet to supply the satisfaction of belief, in his measure and in his style”.

^

“To see gods dispelled in mid-air and dissolve like clouds is one of the great human experiences. It is not as if they had gone over the horizon to disappear for a time; nor as if they had been overcome by other gods of greater power and profounder knowledge. It is simply that they came to nothing. Since we have always shared all things with them and have always had a part of their strength and, certainly, all of their knowledge, we shared likewise this experience of annihilation...It left us feeling dispossessed and alone in a solitude, like children without parents...There was no crying out for their return...There was always in every man the increasingly human self...”

^

I take this to be useable as a criticism of Duncan’s idea. “Is it one of the normal activities of humanity, in the solitude of reality...?... [sic] Their fundamental glory is the fundamental glory of men and women, who being in need of it create it, elevate it, without too much searching of its identity. / The people, not the priests, made the gods. The personages of immortality were something more than the conceptions of priests, although they may have picked up many of the conceits of priests. Who were the priests? Who have always been the high priests of any of the gods? Certainly not those officials or generations of officials who administered rites and observed rituals. The great and true priest of Apollo was he that composed the most moving of Apollo’s hymns...”

^

“...Men turn to a fundamental glory of their own and from that create a style of bearing themselves in reality”.

^

“When the time came for them (the gods) to go, it was a time when their aesthetic had become invalid in the presence not of a greater aesthetic of the same kind, but of a different aesthetic, of which from the point of view of greatness, the difference was that of an intenser humanity. The style of the gods derived from men. The style of the gods is derived from the style of men. / One has to pierce through the dithyrambic impressions that talk of the gods makes to the reality of what is being said.”

^

“The gods are the creation of the imagination at its utmost. Men are a part of reality... It comes to this that we use the same faculties when we write poetry that we use when we create gods or when we fix the bearing of men in reality”.

^

That is: the human creator ceases to be a hubristic or blasphemous concept. This occurred during the eighteenth century — see L.P. Smith’s “Four Romantic Words” in his Words and Idioms — and note how in Donne’s Ignatius His Conclave, 1611 or so, he has Copernicus trying to convince Lucifer to let him into Hell because he is a “Creator”: De Revolutionibus was 1543, by the way! “Shall these gates be open to such as have innovated in small matters? And shall they be shut against me, who have turned the whole frame of the world, and am thereby almost a new ‘Creator’?[“]

[Signing off not included on copy.]

^

. . .Your distinction between revelation and persuasion is crucial, since the godly poet is in charge of the persuasive revealers — that is, a faked fusion. It comes back, then, to something we spoke of before in our letters — the need to read myth without urging a return to the tribal and the shaman: to have an historical sense of the past cultures which actually produced the myths. . . Again and again it turns on what kind of authority is accepted or bowed to enforcedly; the sense of the body’s autonomous power and beauty; the way the word ‘nature’ is used as alibi for action; the place of the man-made, created, in the nonmade cosmos. Your poetry has meant for many of [us] that kind of garden where the nonauthoritarian power is received — what Goodman used to call ‘natural power’, the authentic magic of the artist’s formants [sic], the artist not as a magian ally with some out-there system. Which is where I become sceptical of Castaneda’s admirers — especially over here — I keep returning them to Frances Yates and E.M. Butler and the magus in European and Mediterranean culture — not from chauvinism but from necessity not to ape Indian tribalism, or any other.

^

# I think I am with you 100% in regard to the question of ‘Authority’. Whatever reality I sense in God, in angels, in demonic invisibles, in the Unconkshuss [sic], in the Intellect, in the people (and being a creative imagination in all my entertaining of such entities, their reality has always the dubious character of the imagined), even where I might give them ultimate actuality, I would give them no inroad but rather the fiercer resistance to any claim to authority. Outside that is of the authority that the matter the artist is drawing from and re-creating has, which is the authority of materials. That is, I do find myself studying out the truth of some matter: the truth of all this God and angel and authority business in the leavings of Man. But I’ll stand with H.G. Wells’s noble resolve: if HE does exists, I will resist his claims OVER me. # [...] What I have gotten into in the period (beginning with LETTERS and thickening with the FIELD, ROOTS and the BOW) has its own authoritarian powers over me. The Tar-Baby that works of art become for the artist as he shelters his work under the claims of what he has accomplished. # But I am not willing, have not in mind, any such simple rescue to all that as the casual or cool dismissal of Poetic Superstitions, i.e. as in the New York or the Bolinas modes, proposes. I want to get into the works of Man’s specters. Right now, I am in the works, coming into a renewed CONFRONTATION with the claims of English literature, or, the BIG TAR-BABY, commanding realizations in Poetry that I feel (i.e., with such authorities as Shakespeare and Dante, whose MASTERY in my mind all but overpowers the immediate actual life that is there). # Well, I might revisit The Confidence Man. As you will see from CAESAR’S GOATE (that typo is too lovely to correct!) ah — GATE! I am giving myself a good deal of time, until 1983, before I have to come to the shape of what I am doing. With no BOOK breathing down my neck, I find my ideas somewhat released from the authority of a ‘Duncan’ point of view, which the composition of a BOOK does verge upon as the artist in me seeks out his themes and pursues his commanding patterns towards a total feel. The total feel, I will agree, is first cousin to that politics that hammers out every immediate individual incidental happening to serve as a function of the whole. # Let’s get back to the actual body. A good deal of totalitarianism is founded right there in the erroneous concept that the brain is the MIND much less the INTELLIGENCE. Here Sherrington’s Man on His Nature has been invaluable for me. Once the brain is taken as the actual organ among actual organs and systems of the body; and the actual body is seen to be ultimate and initial condition and identity of a ‘life,’ exemplary of a species of living forms, O.K., but just what it is, no more than the carrier of other possibilities beyond its own limitations then the whole proposition of the individual version of the species within his society (which today is mankind at large, not only all known men in current geographical distribution thought of as being evidence of what the species is, but also men in historical distribution as their ways of living are sought out of archeological evidence and phantasy), does redistribute the feeling of the authority of MAN in our own being aman. # Well, what I am coming from and getting at is that this here idea of MAN has no more authority and the same kind of authority that other imaginations of identity have — as God, or Angels, or ANIMAL or LIFE has. The kind of suspicion of what I would call CONFRONTATION with the IDEA, that is active in your sensing the interaction of confidence, faith, and confidence game, is what I too see called for. Just where inspiration most seems to enter in, we must confront the matter of breath, the matter of wish and compulsion, and (as with all experiences of nouminal power) (not, hold our own, for ‘our own’ in this sense is itself just such an authority) take it all apart, analyse, challenge the nature of the posited reality. # Your questioning whether ‘after Shelley’ there is any seriousness to pursuing the question ‘Who writes me?’ does disturb my conscience, for I do like to flirt with possibilities, fish for possible content. But I trust that where there seems so to be the possibility of an excitement, I have that to confront, tho it might seem otherwise a trivial danger of the tyranny of the ‘real’ or the ‘unreal’.

RD

Robert Duncan, San Francisco, 1985, photo john Tranter

^

Back to our to-be-continued tale of the drama of poetics, fictions, and imperatives in our own time. Along the line of speculations upon such ideas as Dante’s ‘potential intellect’ or Blake’s ‘Creative Imagination’ or Whitman’s cult of the ‘democratic personality,’ it seems to me that a vital field of our imagination both of society, of our life-activity, and of our identity, is ‘super-stitious’ [sic] in character. And once we see it so, that these possibilities — both in their character of limitation and in their extension — are created, cultivated, made-up factors, placed on top of, the necessary, the truly given terms, then the appropriateness of their being ‘Poetry’ rather than ‘Religion,’ an Art and not a Yoke, might be clarified. In answer to a question about whether I believed or disbelieved in the Devil, I got it clear that I neither believe nor disbelieve, I imagine: and I can entirely imagine the existence and I can entirely imagine the non-existence of the Devil. What IS clear is that within what we imagine we can distinguish whether that imagination is adequate to the full range of the idea. The man of religious conviction cannot entertain an adequate idea, for part of the full range is subscribed to as ‘true’ and most is subscribed to as ‘false’. And in Politics too, the true believer is hampered by his subscriptions to what is thinkable and what is unthinkable. We get into all that stupidity in which my interest in Pound’s racism and totalitarianism is to be determined by my ‘belief’ on ‘subscription’ to racism and totalitarianism, or by my liking or disliking of such. I remember Kantorowicz asking in a Final exam in Medieval History: ‘Was Saint Gregory the Great a “saint” and was he “Great”?’ Well, to the degree that one was imagining the situation, that question emerged as what did it and what does it mean that said Pope was ‘saint’ and ‘great’; and along that line we get both into the possibility of an adequate history and of a poetics of event.

^

Whitman repeatedly is inspired to call for a new life, without myth and romance — him in the full intoxication of his romance of Self and Life and Democratic Man — and Plato in his own intoxications of having some special communion with the Truth proposes that we need convenient ‘myths’. Plato’s argument I have always felt was pure fink; man’s trouble with his mythic existence is not with any stories he can ‘tell’ but with the stories that reveal the truth, the real, to him; not with the myths by which you govern others but by the life-myths, the very ground of man’s ‘language-world’ that is superinstated as the term of his reality. Even as we begin to be conscious, we find ourselves in a social ‘Consciousness’, a process in superstition.

Robert

^

I think now, in consideration of your last letters, that what perturbs me is that, in ‘authority’, there is always an historical structure derived from a culture, and so many of the cultures we blandly take our authorities from (an objection to Jung for me) (and to Joseph Campbell) were and are authoritarian — they conserve and promote the authoritarian character, either in submissive or dominant condition (the ghastly twin spectre of destructive erotic need — what Burroughs calls evil: the condition of total need, or addiction — but I have gone into all that in my book on him). So that we are back in our objections to ‘tribal’, in so far as it initiates into being nothing but a transmitter — again, this is where I part from Spicer’s dictated messages, and feel nearer James Koller’s ‘Messages’ in that beautiful Curriculum of the Soul pamphlet of his.[9a] We have to, it seems to me, keep the action of discovering what has gone so wrong in the West, culminating in our time, completely historical and anthropological, resisting any opportunity to reduce cultures to common denominators, at least for the time being, since these are always authoritarian selections under the desire of the reducer. The artist playing with Freudian or Jungian reduction is less safe, for instance, than with Lèvi-Strauss’s reduction (at least in him there is a knowledge of the ‘bricoleur’). As you say: ‘the leavings of Man’. But are we really to descend into them in order to recover ‘images’? Where you wrote in Caesar’s Gate — ‘Images and the language of dreams are not, Freud tells us, to arouse us but to keep us asleep’ — I wrote marginally: ‘but only when we are asleep already’. Living is not sleeping only, after all: with your H.G. Wells’ resistance we have to place what I find my students attached to with tenacity — Pascal’s wager, which I find timid and they find liberal and skeptically tolerant. Caesar’s Gate is a fine metamorphosis of old self into the ‘total reading’ — that’s the phrase I do so like in your book. That and ‘responsibility’, but then you’ve always borne witness to that, which is the centre of our respect. Thinking about conceptual art and poetry lately, and its invasions of New York and Bolinas, and its place here in the Fluxshoe group and one or two other people, their safety in the reconceived is so strikingly opposite to your own risks in the Field: your ill-kept garden which so struck me as the useful conception when I first read you. That is the point of release from that other authority — ‘Duncan’ as he has become: the penalty, I suppose, of having worked so consistently to shape experience in the Field — but let it be said that a recognizable body of work is part of the necessity called ethos (Aristotle’s word for character, I mean). But I do recall that A. says a man has no ethos till he is dead — and the death by fixed ethos before actual death is what a poet has to resist. A toast, then, to your rebirth in 1983.

^

What I meant by belief, which you countered with imagine was: belief is the length of time and the tenacity with which the findings of imagination are maintained. How long do you hold discovery — in this case of the Devil? And in this case too, of the Devil in the context of ‘his’ permanence in cultural history? (That the Devil might be woman is there in Burroughs and yourself maybe). Your term, ‘superstition’ may be something of the order of belief in this sense — is what I was trying clumsily to say. Belief therefore is political and just at that point which nearly interested me the most in Caesar’s Gate — where you place against Lorca’s ‘line of outrage’, his sense of sexual pollution, and his need to purge it, your own fine sense of the puritan purge being the centre of all purgations and the Nazi action in particular in your time, and in mine. Like: ‘The Maypole of Merrymount’ and the burning clean of the pograms. Puritans as perverts — we’ve had our share here (I’m thinking of my own involvements in the trials of Last Exit to Brooklyn and the Unicorn Bookshop in Brighton, in the Sixties): they image invasions from devil-populated space beyond their bodies, and set about establishing cleansing stations. So that that ‘line’ you draw with Lorca, between the passionate abandonment to Eros and the rejection of ‘sexual speculators and pollutors’, is the most difficult of all to understand: it is the centre of what could possibly be meant by the obscene. Let me put with it — I’m not attempting anything else, since there’s no solution — certainly no ‘final solution’ — LeRoi Jones’s The System of Dante’s Hell, where his process is exactly that area you speak of in Caesar’s Gate, and — taking the clue from the ‘line’ — Paul Goodman’s Drawing the Line: where he writes — ‘Once his judgement is freed, then with regard to such “crimes” the libertarian must act as he should in every case whatsoever: if something seems true to his nature, important and necessary for himself and his fellows at the present moment, let him do it with more good will and joy. Let him avoid the coercive consequences with natural prudence, not by frustration and timid denial of what is the case; for our acts of liberty are our strongest propaganda’.[10] So he sets up the idea of a non-coercive community based on ‘natural authority’ — or authority which [is] particular and useful for one thing and does not seek nor is allowed to be totalitarian. Like Galileo in Brecht’s play — ‘Unhappy is the land that needs a hero’. Goodman: ‘The separation of personal and political and of moral and legal is a sign that to be coerced has become second nature....Power over nature is not the only condition of happiness.’And right at the end of the chapter I’m suggesting: ‘social initiation’ not habitual satisfactions or substitutes (state-permitted) for them. That is: the tribal doesn’t initiate, it repeats, the grid goes on and on. The purgation-state is tribal in this sense: it needs the linearity of utter reductive continuity. Back to your exact sense of Marx’s Europe-haunting spectre being not his working class but ‘interference’ — can I take interference as the noncoercive and initiative? That the socialist poet invents forms and anticipates that his life will be spent entertaining interference. To redefine authority as continual invention: but that still, I do see, leaves what to do with that ‘leavings’ business. I don’t really know whether I want any of the ‘leavings’ as such unless they are Monteverdi, Beethoven, Stravinsky, Constable, Marvell — OK, you list them too! Art is not reductive tribal leavings. That seems to me the core of Caesar’s Gate — the wastes Alexander feared are deeply involved in the whole idea of conquest which your ‘empire’ of poetry images suggest to me. I’m thinking of where Lynn White (in Shepard [sic] and McKinley’s The Subversive Science) says: (‘The Historical Roots of Our Ecological Crisis’) — ‘By destroying pagan animism, Christianity made it possible to exploit nature in a mood of indifference to the feelings of natural objects.’ And: ‘Both our present science and our present technology are so tinctured with orthodox Christian arrogance toward nature that no solution for our ecologic crisis can be expected from them alone. Since the root of our troubles are so largely religious, the remedy must also be essentially religious, whether we call it that or not. We must rethink and refeel our nature and destiny.’

See note [11]

^

no private experience no false lord events no

god to turn the sheets

ride in on the surf waves broken under wind and undertow

rise up into and sunlight takes rich foam

break across your tenses skin white where fair brown hair

will glisten against thick blue sky

it happens to everyone so what is the scene we feel to us

carries muscle and pulse across in music

the noises and pleasure cries found

after seeds in a high grey deluge rush to a sea hole

this old urge to remake a someone no one can recognize but know

society become noise

what music can be made to hear

^

ride in to this ancient shore

newly dangerous each year

not to let alternate lives die in crude absence

in streets of cities marked with war arrows

false firstaid kits and below in their bunkers

senile dwarfs hammer their tightened brains

as a last cloud darkens the colossal wave

to address the impending as messenger dear friend in attention

is Eros yes without is under no senile programmes producing refugees

^

to have worn uniform is a difference between us

as we ride in the first sound of that old battleship gun

exploded what youth left

not yet singing in attention

^

seeds flung into mined sea fields courage unknown in the acts of courage

each the undertow draws us out we leap in the dangers

plunge in immense foam in joy

a hope to lose no essential

as even these children are rushing under

into our prison springs where just inland

a rose waterlily fires the lake

formed out of the jet seen in those turning eyes

in a still head of this buzzard that engineers

other currents

other desire

other than revolution the wave ride far inland

crested to an absence where you speak

(1983)

^

Duncan — “An Interlude of Winter Light” — Credences 3 —

“as the river of fire in the poem comes

surpassing what the mind would know” / as against what Snyder calls

“recycling literature over and over again”