| Jacket 35 — Early 2008 | Jacket 35 Contents page | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 25 printed pages long. It is copyright © Kent Johnson and Jacket magazine 2008.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/35/bosnia-diary.shtml

With excerpts from Sarajevo Blues, by Semezdin Mehmedinović

Photos by Forrest Gander unless otherwise indicated

These notes record a visit to the 46th annual Sarajevo Poetry Days conference, held in May, 2007. They were, for the most part, originally written in serial tandem (as in similar travel reports on Bolivia and Chile previously published in Jacket) with observations by Forrest Gander. Thus, the sequence here roughly echoes that of Gander’s report. After we had composed the piece, we decided it would be interesting to publish our parts separately, this time around. Gander’s powerful journal notes of the trip, along with translations by him of some of the young Bosnian poets mentioned here, are forthcoming in American Poetry Review. The boxed excerpts from Sarajevo Blues (City Lights, translated by Ammiel Alcalay, 1998) are used with permission of Semezdin Mehmedinović. — K.J.

Sleepless procession of layovers, delays, slapstick incidents. As we cross the tarmac toward the plane for the final hop from Vienna, Forrest Gander drops his boarding pass in the wind. He chases it, at full sprint, beneath two or three aircraft. He darts left, now right, now forward, now left. Success! The long line of passengers cheers, multinationally.

At last, thirty-six hours after leaving the US, we land in Sarajevo around 10 PM. Mladen Vuković and Dijala Hasanbegović, vivacious twenty-somethings, greet us with warm brio at the gate, ask if we’d like to leave our luggage at the hotel before going out to celebrate our arrival in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Oh, well, we are exhausted, nearly dead, a terribly long trip, we demur.

Yes, yes, we understand, but it is good for the hangover if you stay awake longer.

Dijala corrects Mladen’s English: Good for the jet-lag.

Yes, well, and also it is our tradition that we have a toast of special Bosnian spirits to celebrate arrival of guests to our country, and surely we will make it just one, says Mladen.

The luggage is left at the Saraj Hotel. Our young, battery-packed friends, singing Bosnian songs, return us to our rooms a bit after 5AM.

Billboard for the Sarajevo Poetry Days Conference

Brunch at the Sarajevo Writers’ Center. Woozy, crimson-eyed, we sip soup in between formal introductions to this poet, that poet. Mladen comes bouncing up, beaming, nary a sign of our “arrival celebration” some six hours prior. How are you both feeling? OK? Well, Tomorrow morning, 7AM exact, I take you on special trip: We will visit the recently discovered Bosnian pyramid, which is a structure twice as big as Giza, you see, built by Paleolithic peoples it is said, near present town of Visoko, yes, it’s close, not far, a truly mysterious phenomenon discovered by strange archeologist Semir Osmanagić, very controversial man, therefore 7AM I come to your hotel, you must bring water and good shoes for climbing, I will see you tomorrow, we shall have a most unforgettable adventure.

Did he say pyramid, mutters Forrest, a spoon in his mouth.

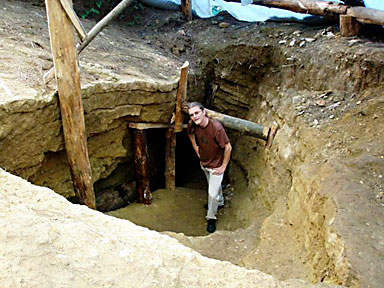

So far, no signage for the convenience of tourists to the pyramid. In fact, there is none anywhere. We wander around through thistle and brush at the base, bleeding from scratches, looking for some path up the towering hill. Farm animals grazing and clothes hung at the back of a few ramshackle homes — two small boys the only other bipeds, save chickens, we see. Which way to the pyramid, kids? This way, sirs! Off and up we go, chasing two giggling elves, through scrub and thorn.

Tour guides at pyramid

I am out of breath, only halfway up. But there is Mladen, two football fields ahead, urging us on. Sitting down, it occurs to me I might have seen something on the Discovery Channel about this, the lead archeologist of the dig (Dr. Osmanagić, I presume) excitedly explaining something about Atlantis and Lemuria, that the pyramid was built on one of the planet’s most crucial energy points, probably with the aid of extraterrestrial technology, as a portal to other Space-Time Dimensions. I confirm later on Wikipedia that my memory is correct… We don’t find any traces of the purported descendants of Atlantideans who supposedly built it all. Only rough-dug cuts and shallow tunnels, timbers to keep these from caving in. The whole project seems more or less defunct.

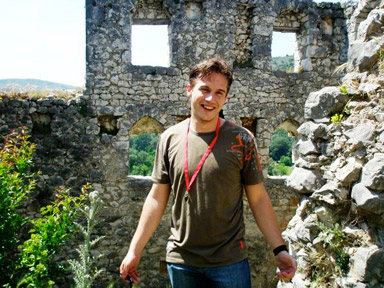

But the day is good, and cheer abounds. I snap a picture of my fellow poet-explorers, overlooking Visoko from the peak, the call to prayer rising from the town as I do.

From the pyramid

Back in Visoko, in Mladen’s old Citroen, driving through the narrow, tile-roofed, small-shopped streets, many of the passerby in their traditional wear, I mention I feel like I am inside a Tin-Tin book: King Ottokar’s Scepter or The Calculus Affair… Ah, my favorite is The Secret of the Unicorn, the very best, says Darko. Yes, yes! exclaims Inuo, Tin-Tin the great! Long live Captain Haddock!… Mladen loudly clears his throat, lights a cigarette. Later, at a roadside café, where a horse munches at crabapples by a split-rail fence, Mladen takes me aside. I didn’t wish to get into argument with Darko, he whispers, Because we once had fight about subject and didn’t speak for days. But, really, Tin-Tin in Tibet is Herge’s greatest work, without question, the very best… By the way (lights another cigarette), have you read last book by Zizek? Since the bombing of Belgrade, the man has gone completely mad, totally insane. He’s now more neo-Leninist that Badiou, and more crazy than Battaille! From where we are, the great hill, three miles or so away, looks like a perfectly symmetrical pyramid, swathed in moss…

Mladen

In Sarajevo, the old bazaar around the central mosque was miraculously spared in the long bombardment of the city by Serbian forces some thirteen years back. Framed in their original oak beams, tiny numbered shops with wooden awnings line the cobblestone streets. Two alleys are occupied by metal-worker artisans, many of them of legendary lineage, the generations stretching back, in some cases, for centuries. In the past decade, a few masters have taken to tapping exquisite designs into bullet and cannon shells, countless thousands of which littered the hills around the city after the war. Here smallish sniper’s shells with miniature lines of verse; here artillery casings the size of trash cans, bearing labyrinthine Moorish designs or pointilistic scenes of astonishing verisimilitude. So you see, says Kennan Ivanović, pouring me thick coffee and turning back to tap away at great velocity, We honor in our art the dead.

1. In the daily reports — when dozen of shells hit downtown, when snipers are in action and only a few have been killed or wounded — we are informed that a relatively calm day has passed.

2. A flustered young man begs to cut into the water line. He shoes his plastic canister. The line twists to make a place for him. Since he’s already loaded his canister, he hurries to the end of the street and gets hit by a grenade. All that’s left of him is a bloody trail on the pavement that’s like sap but is easier to clean. Just then it starts raining and everything gets washed away: not even a trace of the young guy is left, nor a trace of the canister. Just water. As if nothing on the street changed, except everyone got just a bit quieter.

From: Sarajevo Blues, by Semezdin Mehmedinović

Reading

After the opening reading of the Sarajevo Poetry Days conference, I’m interviewed by Bosnian TV. I’m asked something about how U.S. poets are responding to the occupation of Iraq. “Valid I.D.,” a punk rock performance group, the members bearing bizarre headgear, are screaming and bouncing around the stage behind me. I shout some kind of answer back at the reporter. Later, channel-surfing at the hotel, I catch my spot on the midnight news. Subtitles I can’t understand are moving beneath my writhing, inaudible mouth, while behind me five grotesquely faced figures are grabbing their groins, squatting and standing, squatting and standing…

Valid I.D.

Mario Hibert, poet and critic, former teen soldier in the Bosnian resistance, has studied in graduate school the writings of the Russian theorist Mikhail Epstein, who is widely known in the Balkans — his reputation up there with Derrida, Foucault, and so on. Mario asks me over drinks what I think of Epstein’s speculations that Araki Yasusada’s writings are secretly authored by the famous Moscow writers Andrei Bitov and Dmitri Prigov. Not long after returning to the States, I will get news of Prigov’s sudden death — just as I am about to write him and Epstein to tell them about their brilliant young fan in Sarajevo.

Mario, endearingly nervous, presents us in English to a small crowd of twenty, or so, our Monday evening reading at the “American Corner” of the new Sarajevo City Library, a space funded by the American Embassy — a pleasant, large-roomed place with an officially chosen selection of U.S. books. No Chomsky, Naomi Wolf, or Baraka here. Mario and Mladen had gone across the street, hoping to roust up a few young literati drinking Sarajevski pints in the café of the main library. But none of them come. No Americans come either, despite the fact that announcements have been sent out to a large number of U.S. citizens on the Corner’s mailing list. And so, dear listeners, he says, ending his introduction, We are here, eye to eye… Please ask questions as long as you can, have fun, and pray not to end in one of the well-known epigrams or verses that poets misuse to cope with the world.

Carpet at the American Corner

We hear from good sources, including a very earnest newspaper reporter, that we are the first U.S. poets in the 46-year history of the conference to be denied travel funds by the U.S. Embassy in Bosnia. The anti-war poetry did it, they say. Which is an honor, of course, if so… On the other hand, perhaps the war has simply drained all State Department budgets for peripatetic poets. Regardless, would we, in the proffering, have accepted? Complicity wears its many garments. Maybe so…

On the morning I leave Sarajevo to get back for final exams, Mario, emotionally, presses into my hand a small thing. It is for your journey, he says, a modest gift from my wife Monja and me. A little memory. It is a key ring, with a little piece of polished pine attached, and on it, a verse from the Koran, in miniature Arabic, that he has burned into the wood.

With Francis Jones, Mario, and young citizen of Pociteli (D. Hasanbegović)

In Sarajevo, it only makes sense to remember the day that’s just passed. It’s snowing, like it’s supposed to in January. I’m watching kids sledding. They can be divided into those who are in love with their sleds and those who just love sledding. I saw this today and I am very happy as I write about my discovery. I know that, when everything passes, I’ll remember this too…

From: Sarajevo Blues, by Semezdin Mehmedinović

There is an overnight visit to historic Mostar, where some of us read to a large and appreciative crowd. Dignitaries in formal best line the theater’s front row. Having come from a long open-bar reception at the Croatian consulate, we shuffle to the microphone, in t-shirts and jeans, taking tipsy, somewhat farcical turns. Why this standing ovation?

On the bus, all the way back from Mostar, five poets sing, acappella, folk song after folk song. Songs of Bosnia, Croatia, Montenegro, Macedonia, and, yes, Serbia. Now plaintive and sad, now raucous and bawdy. A Balkan barber shop quintet… They have never sung together before, but they know every word and complex melody, dozens of songs. And they seem to know what each other is going to do, what line he or she is going to take. Epic poetry is what comes to mind.

Mosque and river

The lanky, bearded poet Sreten Vujević is a deacon of some kind in an Orthodox church in Montenegro. His voice leads, warbles, haunting and remarkable. Suada Hedžić, one of the conference translators, a lovely, soft-spoken person, dozes beside me, her head sometimes falling on my shoulder. Each time this happens she wakes with a start, apologizes, even though I tell her it’s no problem. But such contact is not proper. For a long time, as we climb and descend the remarkable sheer range that cleaves the country in two (green and lush Bosnia on one side, rocky and dry Herzegovina on the other), she earnestly tells me of her deep faith, of the peace the Koran brings to her life, of its message that all humanity is deeply one, at one in the oneness of God. I listen and don’t ask the questions I have in mind. The river we later follow in the canyon is emerald, now pink, now mauve in the falling light.

When snow falls on Sarajevo, when pines crackle with frost, the bones underground will be warmer than us. People will freeze to death: a winter without fire is coming, a summer without sun has passed. The nights are already cold and when someone’s dog starts barking on a balcony, a chorus of strays answers back, howling in sorrow like children crying: even Irish setters, usually so filled with glee, bark sadly at night in this town, like Ruthger Hauer in the last scene of Blade Runner. Snow will bury this city just the way war has buried time: What’s today? When is Saturday? The daily rituals are dead, just like the yearly ones. Who, in December, will print a calendar for 1993? There is night, there is day: in them are people prepared for the end of the world, well aware that existence in its plenitude would be all but lost were they unconscious of global cataclysm. That’s why they burn a small light at the first sign of dark: the wick pulled through a ball-point refill, a cork wrapped in tinfoil to keep the oil in the lamp made out of an empty beer can burning on the surface. And in the small, clear blaze they can see that intimate objects and faces have an earthly glow, and that there is no grief, until aksham falls, at the sunset call for prayer.

From: Sarajevo Blues, by Semezdin Mehmedinović

Standing sentinel over the city, on one of the many summits surrounding it, the Olympic tower from the ‘72 Winter Olympics looks like some postmodern mosque spire. It is one of the main spots from which Serb gunners sent endless shells upon the helpless inhabitants. An unplanned monument to our times: how quickly good will and hope may flip over into terror and hate.

Even at the height of the siege, the Sarajevo Poetry Days went on. Susan Sontag came at that time, and Waiting for Godot was performed under her direction, even as shells rained down, all around — an absurdly dangerous poetic gesture. Inspiring the whole city…

It almost sounds like one of those many quirky Bosnian proverbs we learn:

Vladimir: Let’s wait till we know exactly how we stand.

Estragon: On the other hand it might be better to strike the iron before it freezes.

First a bulldozer came to dig trenches in the ground, then the truck hauling cement blocks to shore them up. Tanks are dug in with just the barrels peering out. And rocket launchers. Beyond the range of our rifles. Maybe you could even spend the winter in trenches like that. It’s August now: tobacco comes in from Nis and plum brandy from Prokuplje. I don’t know where the women come from, but I saw them too, through my binoculars. One of them put an air mattress down by the trench to sun herself in a bathing suit. She lies like that for hours. Then she gets up, goes to the rocket launcher, pulls the catch and lets a shell fly at random toward the city. She listens for a second, looking towards the source of the explosion: she stretches on the tips of her toes, innocently. Then she goes back, rubbing her body in suntan oil to fully give in to her own state of well-being.

From: Sarajevo Blues, by Semezdin Mehmedinović

In the central city, bullet holes everywhere. Hollow shells of buildings here, relatively intact Austro-Hungarian buildings there. And on every corner, an outdoor café, where everyone is smoking.

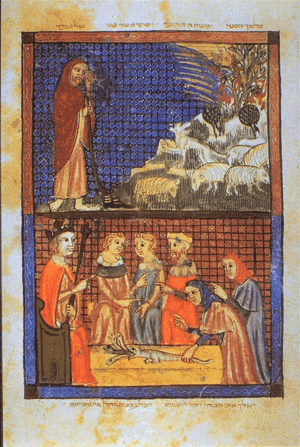

Mladen, learned beyond his years, conversant in six or seven languages, tells the story of the Sarajevo Haggadah, an illuminated manuscript owned by the National Museum of Bosnia-Herzegovina, where it is on permanent display. It is the oldest Sephardic Haggadah in the world, dating from around 1350, considered to be the most beautiful illuminated Jewish manuscript in existence and — with estimated price of three-quarters of a billion dollars — one of the most valuable books in the world. It is believed to have been smuggled out of Spain around 1492, when Spanish Jews, whose culture had long flourished under Moorish rule, were expelled by the Christian Inquisition. During World War II, the book was hidden from the Nazis by Dervis Korkut, the Muslim librarian of the National Museum in Sarajevo, who spirited away the Haggadah to clerics in an outlying village, where it was stowed for some years under the floor of a mosque.

Page from the Sarajevo Haggadah (Wikipedia)

Mladen relates that this happened after a high-ranking Nazi officer, feared for his brutality, appeared suddenly one evening after the museum had closed, demanding the whereabouts of the book. Korkut, coming from the stacks, reported calmly that it had only the day before been taken away by another Nazi officer. When asked who that other officer was, Korkut, life in the wager, answered that he had no way of knowing, since it was not the place for a man of his station and ethnic status to ask a German officer his name. Satisfied, the Nazi commandant left, thinking that the Haggadah had indeed been taken and properly dispatched. And yet the small folio was there all the time, tucked under the heroic Korkut’s belt and shirt. After this, the precious incunabulum was quickly smuggled away and hidden under the previously mentioned mosque… Today it is back in Sarajevo, the purloined gold and copper foil pages glimmering for all to see, in this city of freedom and faith. A book rescued most recently, in fact, in 1992, as shells began to fall upon the library. The hero this time was the Muslim scholar Enver Imamović, Mladen’s mentor at the National University.

The snipers, at least those aiming at Sniper Alley, shoot from the Jewish cemetery. Covered by the gravestones, they’re safe. Dear Lord. Punish all those who desecrate Jewish graves. And punish me, if it was a sin that I picked violets there as a child.

From: Sarajevo Blues, by Semezdin Mehmedinović

We are taken to the new Museum of Literature and Theater of Bosnia-Herzegovina, where there is a terrific exhibit of photographs, manuscripts, and mementos dedicated to Bosnia’s renowned poets of the 20th century. Beneath one of the glass vitrines is the photo of a young man who fought in the last war. A faint resemblance to Wilfred Owen, actually… On one side of the image, a shattered watch; on the other, a handwritten poem. Where the creases are, stains of blood make some words illegible.

Our first-night drinking companion, Dijala Hasanbegović, who is in charge of the seven-citied conference schedule, tells Forrest, attaching the word to his person, that odusevljenje means something close to “overwhelmed with spirit,” or “overflowing with soul.” Word which Dijala seems, also, in her boundless energy, kindness, and wit, to fully embody…

Dijala

That first night, as reported, Dijala and Mladen had insisted we “stay up to avoid jet-lag.” There we are, 3 AM, or so, in a bookstore-café called Buy Book… Against better wisdom, exhausted to the point of waking dream, but enjoying it immensely, I smoke. As we leave, I heave my book-filled bag to sling it on my shoulder and hit Dijala behind me, hard. She is a small woman, and it knocks the breath from her. She crouches down for a few moments, gasping. I’m so sorry, Dijala, I say, mortified. That’s OK, she says, slowly rising and taking a shaky light from Mladen. In Bosnia, two kidneys is a bonus, don’t you know.

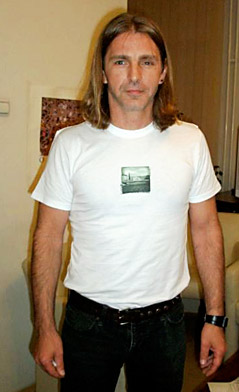

Elvis

On the third day in Sarajevo, I meet my translator, Elvis Mujanović, shy, melancholic young man. Over the ten days together, an unordinary closeness will develop between us. Now, drinking coffee in the hotel, overlooking the city, getting to know a bit about each other, he tells me of his family in the western town of Cazin, how during the war it was taken over by a break-away faction of the Bosnian forces and became the site of terrible intra-Muslim fighting. Imagine the desperation and shame we felt, and always the fear he says, that we would die for nothing. He tells me how his mother, a fan (it goes without saying) of Elvis Presley and a heavy smoker, would hoard all her cigarettes as currency to purchase basic provisions for the family, eating, of the little she could get, almost nothing herself. But he and his two sisters would steal one or two cigs from each pack and store them away to give to their mom to smoke when her depression would grow especially strong. The house gets hit by a shell one day, when they are, for some reason, not there. Relatives and friends die, as soldiers or bystanders. A rotting horse swells to the size of a hippo and bursts all over the road. Medieval buildings collapse into rubble. An old man, driven mad by grief, calmly walks a cat on a leash, as the firefight proceeds around him. Famished dogs snarl over the entrails of the maggot-covered horse. We are quiet for a while. Traffic sounds and school-kid laughter, shouts of daily commerce. And then he lights a cigarette, asks me about my own family, do my parents still live, am I married, do I have children, etc.

Harun, come on, get into the house, it’s grenading outside.

From: Sarajevo Blues, by Semezdin Mehmedinović

By the massive doors of the National Library in Sarajevo, a burned out early 19th century hulk of an edifice, there is a marble plaque which reads, in English:

Doors of the burned library

ON THIS PLACE SERBIAN CRIMINALS IN THE NIGHT OF 25/26, AUGUST 1992 SET ON FIRE NATIONAL AND UNIVERSITY LIBRARY OF BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA. OVER 2 MILLIONS OF BOOKS, PERIODICALS AND DOCUMENTS VANISHED IN THE FLAME. DO NOT FORGET, REMEMBER AND WARN!

Mostar

In the war there are many painful architectural losses. Perhaps the two that most broke the collective Bosnian heart were the destruction of the National Library and the beloved arched white bridge of Mostar.

But now, young divers jump from the beautiful bridge, for tips. The fall is higher than the one divers make in Acapulco, according to Mirza Besirović, smart, funny, charismatic translator for the conference, once an exchange student in Alabama. The solemn young men in their spandex attire spread their arms, ostentatiously, on its railing, wait for photos to be snapped, leap and fall, like missiles, to the green water below… After the war, with funds from UNESCO, the historic structure has been painstakingly, meticulously rebuilt, using almost every piece of its rubble pulled from the river. But not yet the library, which in the deeper sense, of course, never can be: Nearly all its holdings — countless priceless manuscripts and incunabula — were consumed in fire, hit by missiles filled with napalm, launched with purposeful precision by solemn young men, from high in the lovely hills. Our Alexandria, says Mirza, with elegant camp, flicking a lighter, giving a wink.

With friends in Mostar; Suada Hedžić to my left, Mirza on right

In Tuszla, at a sidewalk café with two Bosnian poets: A trio of dred-locked backpackers bantering in loud German strut by. The senior among us, wearing coat and tie, throws back a shot, lights a cigarette: When I was growing up in the woods around Banja-Luka, he says, I used to trap things that looked better than that.

We want to go to Srebrenica, feel we should, to leave something, some token on the ground. Or even nothing. Just some small gesture of presence in the poetically correct manner. No way, we are told: the schedule is packed, the place too far. No time. Some other time.

— Imam Efendi Spahic had three children and a grandchild that were killed by the shells that fell on Dairam. Before that, his wife too; as if God had taken her to Him, to protect her. So she wouldn’t see.

Here’s what I think: There are neither major nor minor tragedies. Tragedies exist. Some can be described. There are others for which every heart is too small. Those kind cannot fit in the heart.

From: Sarajevo Blues, by Semezdin Mehmedinović

Sitting across from a mosque, just looking around, hearing the muffled sounds of prayer inside, thinking of my sons… A little boy scampers into a great flock of pigeons in the square, and up they go, and he claps and laughs. His joy, fleetingly, the very center of the world…

I meet Pedja Kojović, who has translated, with Azra Radaslić, my book Lyric Poetry after Auschwitz, along with other poems, for publication in Bosnia and Croatia. We’d been corresponding for quite some time. Pedja, along with Bosnia’s renowned poet Semezdin Mehmedinović and the country’s leading artist Braco Dimitrijević, is on the editorial board of Ajfelov Most Books, an ambitious new press venture. He shows us the plans and layouts on his laptop: all in exquisite and cutting-edge design. His brilliant companion, Jasna Jelisić, political advisor to the EU Special Representative in Bosnia, talks about the growing fame of Dimitrijević throughout European art circles. The project looks to be a certain hit. Pedja rolls cigarettes for everyone from his tobacco pack, for what’s on the table, as the Bosnian saying goes, is for the table. Roguish, fun, quick of tongue, he was, in his early twenties, one of Reuter’s crack combat photographers during the Balkan war, and he has seen a great deal in his thirty-some years. Three years ago, when Saddam Hussein is taken from his “rat hole” outside Baghdad, Pedja is there, to take the very first images as the tyrant peers up, filthy and forlorn, through the trap door at his captors … This is going to be a wonderful and important poetry series we will do, guys, just you wait and see. We aim to be the New Directions in this corner of the world!

Pedja

Talking with the genial Aleš Šteger, who with Tomaž Šalamun is Slovenia’s most popular poet, outlandishly so, something of a rock star there. He is also — according to Šalamun in conversation with Forrest in Providence shortly before the trip — “the most beautiful man in all of Ljubljana.” Well, no question about it, the lucky whippersnapper. Ah, you both must come to Ljubljana, you must. Everything is beautiful there! With my disposable, I snap a photo of him, and when I get the print, back in Freeport, Illinois, almost the whole thing is a wash of light, as if some envious, minor sun has blinded everything.

Balkan immigration to the southern-cone nations of Latin America in early and mid-20th century was fairly heavy. Juan Octavio Prenz, an Argentine writer whose mother was from Zagreb, presents his remarks (on a panel I also contribute to with Elvis’s expert aid) in fluent Serbo-Croat. Later, near the Sufi shrine in Blagaj, Forrest and I pepper him with questions about Borges, who was his mentor and friend. A soft-spoken, refined man, he is, with Lars Gustafson of Sweden and the Egyptian poet Muhamed Ahmed Hamad, the elder statesperson of the conference, legendary in Balkan literary circles. We tell him we plan to be in Buenos Aires in December and he offers his card. Call me, please. I’ll take you to a great parrillada restaurant, and then we’ll go listen to some serious tango at a good hole in the wall.

Don Prenz, holding pipe, with fellow poets; Kama Kamanda, to his right. Photo: M. Hibert.

Now Prenz is fine, but four days before Blagaj, he had been briefly hospitalized after collapsing on a hot day; only hours before that, the Egyptian poet Muhamed Ahmed Hamad had been rushed to the hospital, too (he is fine now, as well, we believe). Oh my God, cries Dijala, grabbing her head and lighting a Walter Wolf in seamless sequence. This is going to be ‘The Dead Poets’ Society Conference of Sarajevo!’

In Tuzla, Inuo Taguchi, from Japan, recently awarded the top prize for younger poets in his country, skips to the stage barefooted, reads with great force a poem about a man who drinks too much and turns into a bear. I give him Doubled Flowering at the end of a night over some alcohol between us. A poet with heteronyms, he knows of it. He takes it, bows, touching it to his head. O, I see it is in a plastic! he exclaims, commenting on its shrink-wrapped covering. It is like a condom, no? Aha! A book in condom! O! No, no, poetry must never have condoms, he says, ripping off the offending prophylactic. Lovely man.

Forrest has a thing for collecting foreign words, tweaking out their semantic resonances across cultures. He says that the Bosnian word sabur, latest on his list, means something like “demeanor,” though more in the sense of “demeanor as unfolding” — the rhythm, as it were, of how one bears oneself in time.

Damir Imamović is Bosnia’s leading folk musician, grandson of Zaim Imamović, one of the greatest-ever performers of traditional sevdah song. After a group reading at the Writer’s Center, he comes on stage. Accompanied by violin and bass, his voice and guitar merging into a single thing, Damir sets loose exquisite, deep-souled braids of sound. He seems taken over by some kind of force. The audience is transfixed. Sabur.

The woman in a seat near you is talking to herself. Fine — she says — All right. Just don’t touch. All eyes turn to you and you also turn to see who’s at fault. Ashamed, you turn back, biting your shoulder. You feel the weight of the girl sitting next to you, the warmth of her shoulder. You find yourself in the toilet with a Sarajevo rocker — Jewish — and while you take a leak together you bond in perfect male solidarity: That’s how it is, says the Jewish guy. And you nod even though it isn’t like that. Nothing’s for sure except 2 circumcisions by the flushing bowl. Without you everything in this town will still be the same. Or almost — you reassure yourself. So remember a few details, and all the instances that mercilessly surround your awkwardness: the clash of teeth in a kiss, for instance…

From: Sarajevo Blues, by Semezdin Mehmedinović

Jokes are legion: “Mujo” is usually the star, and the jokes usually revolve around his consumption of alcohol.

Darko Jezildžić, translator of Japanese, twenty-some guy with Hollywood looks, big fan, interestingly enough, not just of Tin-Tin, but of both Walt Whitman and Ron Silliman, takes a gulp of beer and offers one:

Mujo decides he will give up alcohol. He walks to usual pub, sits down and tells to bartender: “Give me a juice.” Bartender, surprised, ask: “Which one?” Mujo stand, perplexed: “There’s more than fucking one?”

Darko

In Sarajevo, cosmopolitan but strongly Muslim city, do not cross your legs, cowboy style, the way that insultingly exposes the sole of your shoe. Cross it European style, so the sole faces the ground. And don’t allow your eyes to linger for long on any woman, beautiful or not, whose head is covered with a scarf.

Talking late at night with Stevan Tontić, one of the country’s major poets, as we wander the old section of Mostar. He asks me what I think of Robert Creeley’s poetry. I talk enthusiastically, as another poet translates between us.

Yes, yes, he says, breaking into English. Creeley, I love him. I LOVE HIM! Eternal, Robert Creeley… Eternal, yes? This is how you say?

Yes, yes, I say, and we put our arms around each other, and walk like this in silence for a little while, content in our communication.

Who do you think is a better American poet, a young poet from Macedonia asks me in Mostar. Wallace Stevens or Lorine Niedecker?

Ah, they are very different, I say, chuckling somewhat patronizingly.

I know, Mr. Johnson, she says. Believe me, I know. This partly is my point in the question. I wish to converse…

During the war, Radovan Karadžić was the President of the breakaway Serb region of Bosnia-Herzegovina. Still in hiding and accused by The World Court in the Hague of engineering genocide against Muslims and Croats, he was, before the war, a practicing psychiatrist and published poet. Jasna Jesilić explains that these occupations were not, however, his greatest claim to fame, before his career as a war criminal. Oh? What was it, then? I ask. He was one of the best-selling authors of children’s literature in the Balkans, says Jasna.

Standing by the window, I see the shattered glass of Yugobank. I could stand like this for hours. A blue, glassed-in façade. One floor above the window I am looking from, a professor of aesthetics comes out onto his balcony: running his fingers through his beard, he adjusts his glasses. I see his reflection in the blue façade of Yugobank, in the shattered glass that turns the scene into a live cubist painting on a sunny day.

From: Sarajevo Blues, by Semezdin Mehmedinović

Attached to Sarajevo’s five-hundred year old central mosque there is a little fountain — two ancient copper pipes, really, protruding from an ancient wall. It is said that upon drinking from this fountain, the visiting drinker becomes Bosnian and is given his or her true name. A couple days before, Forrest had drunk from it and been baptized, to hilarious laughter, as Semsudin Gusić, a clever play on his unusually evocative appellation.

With Forrest, aka Semsudin Gusic, outside Sarajevo. Photo: I. Taguchi.

Two days later I bend down myself, drink from both spouts. Your name is ‘Kennan Ivanović,’ says Mladen. There is no laughter. What does it mean, I ask expectantly. Not much, says Dijala: Kennan is a common name in Bosnian… And Ivanović, adds Mladen, is just like ‘Johnson.’

Later, it occurs to me, with a shock, that my new name is the very same “not much” name as that of the metal smith tapping into the cannon shells, the one with whom I’d spent a magical hour in the old bazaar. Unbeknownst to my baptizers…

We are drinking coffee near the Writer’s Center. The call to prayer rises, cascades in haunting song across the city from all the mosques.

That is so gorgeous, I say to Elvis, Mario, Mirza, some others.

Mirza blows a smoke ring. What’s gorgeous?

That, I say, pointing at the sky, The call to prayer.

Oh, that, says Mirza. We hear it so often, we don’t even notice…

Oh, I say.

By the way, my dear-friend-so-enchanted, he says, Have you ever read Edward Said? (goodly amount of teasing laughter does follow)

At the Croatian Consulate of Mostar, the poets are feted in grand style. Speeches by politicians, flowers, fine hor d’oeuvres, bow-tied waiters, free booze. The Bosnian poets, I notice, seem pretty unimpressed. They ignore the ashtrays, putting out their butts on the patio, grab whole bottles of wine from the bar table. Kama Kamanda of Congo, recent nominee for the Nobel Prize, is the most noticeable presence among us (for he is Olsonian in scale and owner of a resonating laugh that seems plugged into an amp). He grabs my elbow and says, Oh my, I do believe there is a bit of tension here. Oh, yes, a bit of tension there is, my friend. Like all poetry conferences of the world, indeed. You should have seen it in Havana, where I just was… HA HA HA HA!

Poets greeted at the Consulate of Croatia

Our bus pulls into Medjugorje, where the Virgin Mary is purported to have appeared. After Fatima, in Portugal, it is the second most-visited site of the Virgin’s Vatican-recognized visitations. With Ismail Bandora, of Jordan, the leading translator into Arabic of Bosnian literature, I go to a café, a place full of crucifixes and catholic icons on the walls. All for sale. We have cups of Bosnian coffee, cigarettes, talk about Palestine. An eloquent, intensely attentive man, he asks me many questions. What do I think about Iraq? Do I know that the death toll is much higher than is reported, not only for civilians, but for US troops, too? What do I think about Palestine? I try to answer, ask him in turn about the conflict building between Hamas and Fatah. He grows sad, tries to explain, says he wants to invite me sometime to his country. It is a beautiful country, Jordan… We sit, we smoke. The faithful shop for talismans around us. What do you think about this Virgin Mary apparition? he asks. I hope she will save us, I say. Yes, good answer, he says. May I have a light?

A body just about to be buried. I see a soldier on his knees: still a kid. His rifle rests in his lap. You can hear the guttural murmur of Arabic. Sorrow gathers in circles under the eyes; the men pass their open palms across their faces. As the rites continue, I feel the presence of God in everything; when this is over, I will take a pen and make a list of my sins. Now everything in me resists death: as my tongue passes over my teeth, I can sense the taste of a woman’s lipstick. No one is crying. I keep quiet. A cat jumps across the shadow of a minaret.

From: Sarajevo Blues, by Semezdin Mehmedinović

Pociteli, with castle tower upper left

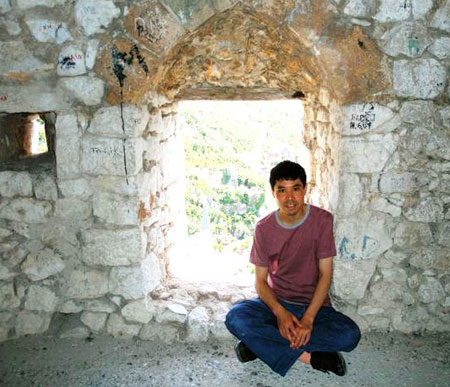

Pociteli, overlooking the Neretva River, austerely magnificent, a kind of Balkan Macchu Picchu, only that people still live there. A castle, its ruins still crowning the town, was built here by the medieval Bosnian king, Tvrtko. As I climb hot cobblestone steps, struggling toward the great tower on the summit (memories of the pyramid), I look far up and see Inuo, his head and arms poking through its topmost aperture, waving and yelling: Hello, Kent! Hello! Be careful, Kent! Don’t turn into a bear!

Inuo, overheard talking to Dijala, as we drive through the great granite canyons: No, because you see, I feel that poetry must strive to open giant air holes in human consciousness…

Inuo, in tower of King Tvrtko’s castle

To Blagaj, the searingly beautiful place previously mentioned, where a great river, the Buna, has its source deep inside a cave. The cave sits at the bottom of an astonishing, precipitous wall of rock, one to give El Capitan in Yosemite a run for its money. Perched above the cave, a Sufi shrine, dating from the 1500s, which one can visit for a fee, as we all do, taking off our shoes…

With the German poet Uwe Kolbe and the superb UK translator Francis Jones we walk, after drinks, down a poppy-lined path away from the cafés of Blagaj.

Stop! says Uwe.

What?

Shh. Listen! (birdsong, half a minute, or so)

O, that’s lovely, what is it?

A nightingale, says Uwe.

A nightingale?

Shh.

And from behind a riot of roses, by an ancient stone house, a nightingale startles off across the gin-clear river.

Uwe

Days earlier, Senadin Musabegović, a poet, critic, and veteran of the war, had introduced the opening reading of the conference, a rousing address to a crowd of a couple hundred or three. Afterwards, Forrest is interviewed by Senadin for his weekly television show, the Bosnian equivalent of C-SPAN Book TV, though unlike the US version, it is prime time and on a main channel. Questions about empire, slaughter in Iraq. A question about the politics of poetry, a question about being a poet in a country bringing suffering to so many… This speaking here, says Forrest late that night, a bit tipsily, as we climb the road back to the Saraj Hotel, Where does it go? Who are we to talk here about war? Or was it I who asked that? Fuzzy poetry-tourism recall…

The Chetniks banished the mental patients from Jagomir to the city. That day, one of them — holding the body of a dead sparrow by its claws — came up to someone walking along King Tomislav Street and said: “You’ll be dead too, when my army gets here.”

From: Sarajevo Blues, by Semezdin Mehmedinović

A few days later, we are introduced to Amra Pandžo, the wonderfully welcoming and jovial Director of the American Corner of the Sarajevo City Library. Before the reading, she and I stand outside and talk. She is Bosnian and Muslim. Her husband is Serbian. Already, their six year-old son is taunted by his classmates because of his father’s origin. It is very difficult for him, says Amra… Last week, I was tucking him in, and he began to cry: ‘Mommy,’ he cried to me, ‘Sometimes I feel like I have two hearts!’ Do you see how it is? And then she lowers her head, grasps my arm, and quietly cries, too. I swear this memory is perfectly precise.

Goodbye, Kent, I will never forget you.

Goodbye, Elvis, I will think of you often.

The tour guide, in awkward English, explains the history of the Sarajevo Tunnel: the city’s hand-excavated lifeline to the outside world during its thousand-day siege. What she says is memorized, I notice, from the pamphlet I purchase at the entrance. It reads:

After the lasting several months of brutal struggle with the misfortunes that accompanied the construction, permanent shelling, the lack of tools and water pumps, underground waters and similar, on 30 July, 1993, at 21.00 pm, two diggers, digging from the two opposite directions, offered a hand each other, the hand of hope, the hand of victory. Sarajevo has got, indeed very small, the opening into the world. A total of 2800 meters of ground was excavated, and 170 meters of the wood and 45 tons of iron building materials were built in. The tunnel was 800 meters long, with the average height of 1.5 meter and average width of 1 meter. Because of the permanent shelling, the tunnel was installed with a pipe-line that was used for the delivery of oil for the town, then the mail-cables were also laid on, and thanks to the donation of Germany the electro-cables were placed down so that Sarajevo has got a minimum of electricity and telephone lines with the world. During the blockade of a thousand of days, the tunnel was both the hope and salvation. Through it thousands of tons of food stuffs, military technical mines, fuel and medical material used to be delivered through it, the most difficult wounded persons used to be delivered, soldiers, functionaries, and military superiors came in and came out. The tunnel has become a symbol of the resistance of the unarmed people to one of the most powerful armies in Europe.

What is political poetry, Kent? says the Bosnian poet crouching next to me, on wet boards, as we peer down into the tunnel’s dark. One can say it is this or that, but at certain times, you see, the task is just to dig…

I was coming back to Sarajevo the only way you could: through the tunnel. Water seeped in everywhere through the narrow passageway; the mud made it even harder to get through. Since there wasn’t enough air, I became so exhausted that I had to to stop halfway. I was ready to lay down and die right where I was till I found a spot that was a little wider, made to put aside the dead, so the living could pass. I stayed right there, for hours, underground, and thought of Radovan.

From: Sarajevo Blues, by Semezdin Mehmedinović

In the foyer of the Composer’s Hall, after the final reading, a figure that is massive, a drink in each hand, coming at me… He stops two feet away, opens his arms, bellows with a voice to crack all walls: KENT JOHNSON! I HAVE A WORD WITH YOU!

It is Admiral Mahic, and this is his actual name. Spitting image of an aging, abandoned heavyweight boxer who sleeps on a couple layers of cardboard, near a subway vent. His matted, greasy hair, pockmarked nose, his great belly showing through popped buttons on ludicrous Hawaiian shirt, stained pants hanging hip-hop low on humongous hips, battered, dust-caked shoes… He is revered by the young poets of the Balkans, a legend, their Ginsberg…

Admiral, at the Buna River. Photo: D. Hasanbegović.

As Admiral and I slowly walk along the Buna River in Blagaj, making our way back toward the shrine above the mouth of the cave from which the river pours, he says, in (now) quiet, gravelly voice, as he lights, yes, a cigarette: You know, I write poem some years ago about this river.

Really? What do you say in the poem, Admiral?

I talk to river. I ask river: Where is my mother? Where is my wife? Where is my daughters? Where is my son? And river only answer with sound of the roaring water… So this is my poem. Very popular, I afraid, in Bosnia-Herzegovina.

My father died. Not here, he was in another city under siege, in Northern Bosnia. I love him as much as a son loves a father and I still haven’t gotten used to the feeling that he’s gone. I put off my encounter with his death and, now, when I think of him, the images that come to me are joyous and sad, innocent…

With sharp pruning shears my father cuts the dry limbs in the warm April afternoon and sings, Hey, I’m cutting the pearly apple…

From: Sarajevo Blues, by Semezdin Mehmedinović