| Jacket 35 — Early 2008 | Jacket 35 Contents page | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 14 printed pages long. It is copyright © Michael Gottlieb and Jacket magazine 2008.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/35/gottlieb-jobs.shtml

1

¶ 1

We sit in our rooms. We write. We try to read. It begins to grow dark. We switch on the light. We wait for the world to come to us. Or, we don’t. We start asking ourselves questions. Others arrive unbidden.

2

One of the questions: what kind of jobs do we, should we, as poets, end up with while we do our real job?

3

¶ 2

What kind of job are poets ‘allowed’ to do? Academic? Starvation wage ‘culture’ jobs? Copy shop? Proofreading? Marrying for money? ...Trust fund poets (how many of them float around, incognito, clad in their carefully shabby protective coloration)?

4

And yet, nothing is better than this. Nothing is better than doing this–sitting up til all hours all alone, accompanied perhaps by ashtray and glass, listening to the trucks shudder up Lafayette or across Kenmare or along Amsterdam or the BQE or the Gowanus or...

paragraph 5

So, naturally, we would prefer to do nothing else, wouldn’t we? Even though, as Beerbohm rightly pointed out, you can’t do this more than about an hour a day. So, is it that we take the path of least resistance? That is, ‘I’ll do whatever is least taxing so I can do what I really want,’ or is it something else? Might it be that what we fear is really that ‘something else?’ That what we fear is that we cannot ‘make it’ in the world. The ‘real world’–as we used to call it in college. Or, alternatively, is it that we just, quite properly, perhaps, recoil at the prospect of the demands, the compromises, the indignities, the surrenders that such a life appears to require?

6

So, how do we end up? Proofreading? Adjunct teaching? English As A Second Language? Construction? Bartending? Junior-assistant-odds-body? There was a time when some people got gigs writing pornography. You don’t hear much about that anymore, probably because it was, in fact, pretty hard work. Some folks did typesetting, back when that was still a job. The apparent fact that these kinds of abnegation, this embrace of what some would call the ‘menial’ is a common or typical or credible option for us ...what does that make us? Cleaner? Purer? Less compromised? But is that sort of work any less compromised than working for, say, the government or for a big company? How, by any law of political economy can that be so? What are we buying into, supporting? What’s the difference? Or, is it just ‘easier,’ somehow, to have a crappy job? What do we trade off by not having to make any of those so-called trade-offs? Does one gain any more time for writing, or accumulate a stronger inclination to write, or a deeper aptitude for writing?

7

¶ 3

What’s wrong with working in a copy shop for twenty years, anyway?

8

Why is it, or is it, wrong to live like a graduate student? That is, like a slightly-well-off undergraduate — one step up from that especially luxurious poverty — for twenty years or more? Is it somehow wrong to camp out for decades in a cramped studio on Avenue C–back when that was the best address that a poet so situated could afford?

9

Moldering away there — crowded out by one’s books and magazines, all stacked up on plank and cinderblock shelves — who have decided the place belongs to them? Why is — or is it ? — wrong not to have insurance? To always have to scrimp? Never taking a cab, always having to do your own laundry, never taking a vacation?

10

Not just hating what you do, but hating yourself for doing it? Never going out for a nice dinner in a decent restaurant in the West Village just because you feel like it, because it would mean a whole week’s salary. To have to keep wearing every article of your clothing until it wears out. To look at everyone who walks in the door of the store who is dressed more expensively than you as someone who is somehow ‘wrong.’ Who is corrupt, or a fascist, or a potential criminal. What does it mean when you come to the pretty pass when you see any other way of living as a selling-out? And when you assume that every other life must be just as joyless as yours?

11

¶ 4

Some would say things are different now.

12

No one can afford to live in, say, in New York, the way we did decades ago, some would say. The realities of the real estate market have changed all that. Poets have to have jobs now, real jobs, middle-class jobs. You just cannot live off a lousy job now, or a lousy part-time job. Poets can’t afford to live out the old fantasy anymore.

Maybe people aren’t working in copy shops anymore. But, for some people, nothing has changed. Aren’t some people still making the same sort of portentous choices? Those first coming to the city? Those first launching themselves into this life? As opposed to those who have ten or twenty or thirty years invested in their choices and may naturally feel the need to defend them?

13

¶ 5

Can it be, as is the opinion of some, that self-destructiveness is out of favor these days? That you can’t show up falling down drunk at readings anymore? And, further, is it true, as some also aver, that most poets have decent jobs nowadays? Is this so, or is history repeating itself? In fact, is it possible that we really see, generation after generation, the same patterns occurring and reoccurring?

14

Are we all so well-behaved now? Is no one out of control anymore? Is no one getting fucked up anymore? Doesn’t anyone grind up prescription pills anymore and share them round on a piece of mirror? Isn’t anyone moving out of town, leaving New York, because they can’t take it anymore? Does no one drop out so they can drink and play pool anymore? Is no one sitting at home with his or her kids in Brooklyn remembering bitterly all the years they ran a reading series and invited everyone on earth to read — and tediously conned up intro remarks for each and every one of them — and now no one, no one in the whole wide poetry world ever, ever calls on them? Does none of that befall anyone any longer?

15

¶ 6

How or when or why has our job changed compared to the job of the painter, the artist (that is to say, why have we stayed so poor)?

16

Or was it always different–if so, why are there so many more of them? How has the art world become a phenomena in this apparently expanding, exploding universe of wealth? ...In the same way, there used to be a handful of expensive restaurants in the city when we were young and now there are hundreds. Now there are hundreds of galleries in Chelsea when there used to be a few dozen in Soho a few decades ago and a mere dozen or so in Midtown a few decades before that. Now they are everywhere, the artists — compared to us. What does that say about us? That we seem to be so few and, moreover, that we are all staying poor, or relatively poor?

17

The idea that we are both really doing the same thing — but they can get rich doing it — and their old ’uns are given the Legion d’Honneur and ours the daily noodle special at Dojo — tells us exactly what? Does it tell us that there is something about us, or them, or what we respectively do, or, perhaps, the world itself that we all are obliged to live in? But we know it is the same. What we — the painters and the poets — do is the same. Is it that it is just too difficult, or too easy, to buy a poem?

18

¶ 7

What were the prospects we thought we had before us in thirty years ago?

19

No one cared. But maybe that was just the way we were thinking three decades ago. What were we thinking? Some of us though, obviously, were thinking, and thinking ahead, in fact. The rest of us were just being poets, downtown poets, New York poets. We lived in that world, that small press, downtown reading scene-world. That was the scale and scope of our horizon. We didn’t, we couldn’t, and if anyone could possibly have asked, we would likely have responded that we shouldn’t have had any greater ambition than that. No one wanted us anyway. No one from ‘uptown,’ no one from academia. They hated and disdained us. And certainly feared us. And that was all entirely proper and correct. Our painter and dancer and musician friends were in precisely the same boat, or so we thought.

20

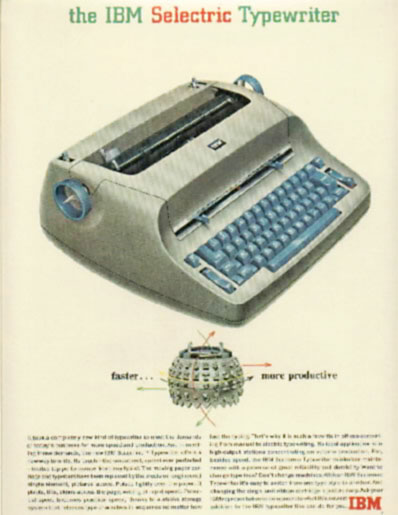

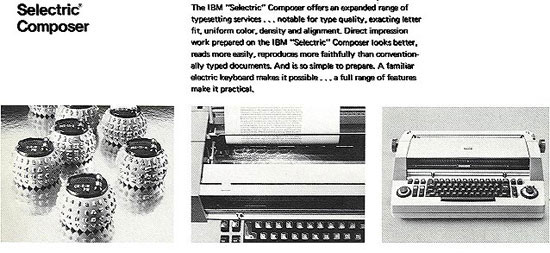

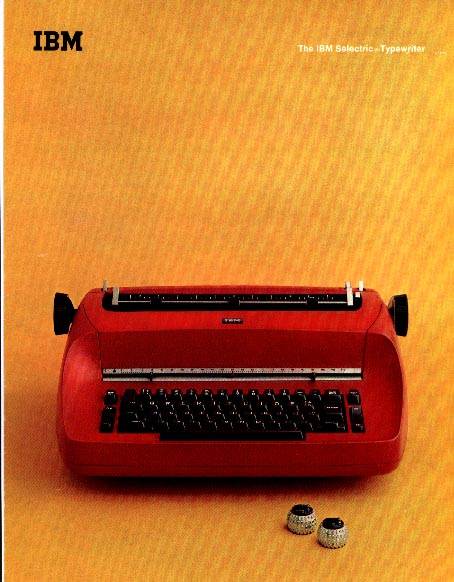

We published each others’ poems. The Xeroxed books at first — it wasn’t so long since mimeo had ruled the day. Some of us had special staplers that could do saddle stapling, but not many. They were expensive. Some of us had IBM Selectrics typewriters, but even fewer. They were extremely expensive.

21

There was a remaindered paper dealer on Broadway, below Houston, behind a Latin women’s-wear retailer named Yo Linda! You could go back there and find cheap card stock for covers and lovely sheets of tissue in all sorts of colors for end papers. I always assumed they once owned the buiding, or at least the lease on the ground floor. And, like a squabbling brood of Czarist nobles crowded, after the Revolution into the butler’s pantry of the mansion they’d once owned, they’d been progressively reduced stacking their teetering piles of stock at the back of the ground floor which we now roamed. There’s a Banana Republic there now.

22

¶ 8

How has that changed for the second, third, fourth generations?

23

Somehow — how? But we know exactly how, don’t we? Somehow, in a way that seemed impossible for us back then, or all wrong — that tenured, or, at least adjunct, lifestyle — one which it seemed ridiculous for the likes of us back then to even countenance, somehow that lifestyle now has become normative, normal. And why? How could this have come to pass? And at what cost?

24

¶ 9

Is obscurity good for poets? That is, why must we remain unacknowledged legislators?

25

Are we not most at home when alone in a crowd? Might it be better to pass along Fourth Avenue unnoticed? To walk among our fellows on the pavement in front of the Strand, as if we were no different than them, because, after all, we are not. To listen and to look unhindered, unrecognized, does that not give us the greatest agency, freedom, that any artist could ask for? We are just like everyone else — we should be, we have to be, we should be proud to be so. We just do one other thing — one thing in addition, one thing different than everyone else. The fact that no one pays the slightest attention to us only redounds to our benefit. It permits us to do our job better, easier.

26

And how much more obscure would we all be if some of us had not become academics and so made sure that at least someone is reading some of our books, year after year?

27

¶ 10

Is the academic lifestyle healthy for poets?

28

So, in a way that frankly was completely unthinkable thirty years ago, at least to many, if not most of us, somehow this came to pass. Where and how were the seeds of this transformation embedded in our original, critical, valorized proposition? Now this tenured life is a normal way for poets like us to live. But what is that life like? What are the pressures? Are they more or less than any other job? And what about mobility? Does this profession give one more, less, or the same amount of freedom to maneuver, to move around, than other possible ways of making a living? And what is the ease, or lack thereof, when it comes to moving from stage to stage, or level to level in that world, compared to any other? How important is that anyway? Trapped? Are we not all trapped? Or, are we all equally trapped?

And does it pay more? Well, we know it pays more than working in the copy shop. At least it does eventually. And, lastly, is that world more or less hierarchical or stratified than others? Does it require the same or less amount of obeisance? Does it oblige its denizens to acknowledge designations of rank, status, title and perquisite more than other ways of making a living?

29

¶ 11

Is the ‘business’ world worse?

30

Is any other world less hierarchical than academia? Less mobile? With more pressure to conform? Or, are they all equally oppressive? One can answer what one will to those questions but behind them is another question: how much more morally compromised is the business world for example, bearing in mind how it is linked, however, to the profit motive, to the corruption and evil of capitalism? How much more is it connected to some more or less base dimension of commerce, of deception, of filthy lucre? And, if so, how much more corrupt is that life than an academic life whose economy is itself as we know, a vast dependency upon the largesse of the State — regardless whether the institution in question is a public or a private one. Do not all colleges and universities, by virtue of their utter dependency upon grants and other public funding, therefore become instrumentalities, both economically and morally, of the state? And for those whose endowments liberate them from that dependency, where and how are those endowments invested?

31

What does that leave us with? Teaching as an intrinsically ethical activity? Let us stipulate to that. But what does that say about all the other pursuits we could follow, all the other things we could spend our days doing? Working in a copy shop on Seventh Avenue, or working in an advertising agency on Madison Avenue? Providing a good or a service to others? Working for some non-profit on Park Avenue South and accepting the delimiting compromises that demands — those bien pensant indignities? Or, one of those dead-end jobs at a trade publisher, with its veneer of culture and decorum and its false-front of non-commercial security — but even more boldly underpaying? What are the ethical dimensions of what you spend your day doing?

32

¶ 12

Is the academic lifestyle so much more ‘congenial’ for writing, for poetry?

33

How many of us really want to be teaching? Would any of us have become teachers if we weren’t poets? Is it that that lifestyle seems to ‘allow’ the most time, for poetry? How many, as some occasionally ask, enjoy having what passes for the power over others that a teacher wields over a student? But — if there was another, equally remunerative path, apparently equally undemanding, equally morally comfortable — would we take that instead? Or, is it that we are also frightened (not just repelled) by the ‘real’ world? The business world? Do we fear that we could never survive there?

34

¶ 13

So, what is the difference between working in a copy shop and an English Dept? Is it not possible that both are equally ‘relieving’ of responsibility and both equally, safely, ineluctably, distant from the life of the writing mind?

35

That drafty, sooty shop on St. Marks or Eighth Street or Broome Street or First Avenue or Sixth Avenue, with its soiled matte white paint and jerry-rigged carpentry, its awkward, amateurish signage; its tired equipment and bickering staff. The ugly looks that fall like rain on the boss whenever he chances to fall by, the petty pilferage. The anger that just continues to build...

36

¶ 14

Or, could some argue the English Department life is, really, after all, more conducive, more sympathetic for a poet? That the fight over the corner office, for the department secretary’s hours, for the next sabbatical — that is all good. It engenders, indeed, it furthers our project.

37

But if we end up saying that writing is indeed as distant from teaching as is working in a copy shop, why pick one over another? Because teaching offers better pay and benefits and a sabbatical? The impact of those facts certainly cannot be underestimated. They are vital for the sustenance of our mind’s life. That sounds like reason enough. But are there any other reasons? Or, alternatively, could it be that there are reasons that would make a life in a copy shop superior, more conducive, more sympathetic, more ameliorative for the life of a poet? Is it possible that life in the English Department in fact forces compromises upon one that spending eight hours a day bent over a Xerox machine does not?

In academia, might there more pressure to conform, for example? Pressure, specifically, to ensure that one’s writing aligns with the aesthetics and literary politics of those — to conjure a wildly hypothetical example — who are in a position to do one a good turn or do one ill; say, the head of one’s department or those who have a say in one’s future, when it comes to writing recommendations, or the granting of tenure?

38

¶ 15

Why shouldn’t poets be the free-est of all artists? Freed from any economy, freer than any to do whatever they wish? No capital, no infrastructure, no collaboration required?

39

What is holding us back? There’s no money in this anyway. And no one else cares, anyway. To the extent that we are actually unlettered, untethered — except possibly if we claim we are academics, and our work, as poets, our lives as poets, have no relationship whatsoever to what puts our bread on the table, because that is simply a fact for so many of us — it should follow, perforce, that if our only responsibilities are to ourselves, and each other — as defined as those who are with us now, readers as well as writers, and those who have come before and those who will follow — why, by all that we hold dear, are we not the most free?

So, one might ask, why does there appear to be more conformity now in our world than there was, say, twenty or thirty years ago? When the Gotham was still on 47th Street, when it was still open, and there were just one or two magazines to be found there with anything in them along the lines of what we’d today recognize as the product of ‘us.’ That is to say, are poets more in lock step? More attentive to how they are different rather than how they are the same? If that is so, can that be simply due to what we can call a ‘maturing model’ that our type of writing somehow has found itself tracking? That at this stage a refining or winnowing away has already taken place?

40

Perhaps it is ‘our’ problem — as in ‘us,’ the older poets. Perhaps we have been around too long and we are no longer capable of reading the way we used to. We cannot perceive the real differences, the actual variety. Could it be that it all may so often seem of a piece to us because our eyes have grown dull? In the same way, that, to some, all the rock and roll produced after their own particular youth has come to a close, which is when they themselves stopped listening closely, starts to sound quite the same?

41

Or, are our expectations all wrong? How many of us — that same ‘us’ referred to in above — somehow find ourselves wishing for some cataclysm, some violent overthrow, some one or some group to come along and definitively reject us? Some ‘next?’ Some clear and definitive full-stop? Something to come along that will be so new that it will sweep us aside? We have had our day, haven’t we? It is as if our ultimate validation, as a movement, as a school, as individual artists even, perhaps, can only come from our passing.

42

Alternatively, to return to the present, to the here-and-now, to the situation in which we find ourselves and which many would say in which we’ve been immured for perhaps a couple of decades — if there is indeed some more uniformity in what we read, is it possible that it is due to the fact that so much of what people are reading, when they come upon this writing, is presented in a classroom setting, in the form of a syllabus? And, if so, it is a reading list selected by ....who? Is it also possible that, further, as these young ’uns begin to write, so much of the criticism and response they receive is modulated in the venue of a credit-bearing writing workshop led by... who? Who among our peers or those who have come immediately after us and who may be tenured or themselves strive for that rank?

43

¶ 16

What does it mean to be so free that one has no audience save other poets?

44

Does it matter who we write for? An audience that is not here yet? An audience that never will be? An audience that is dead, living, yet-to-be-born? Do we write for an idea, not an ideal, but an idea of an audience? Because mustn’t poetry be written for all of us, including those who ignore or refute or spurn us and our activity? Like, for example, those who used to venture into the bars where we used to read, like the Ear Inn, looking for a game on the TV, and retreat, smirking when they realized what they had blundered into. So that we, all of us, can be what we have to be. We, ourselves, are as good an audience as any. For the time being, at least. Maybe forever. And why shouldn’t we be?

45

¶ 17

If communitarianism is what we like to believe is the equivalent of a market in this poetry world, its currency is, what, exactly? Interaction? Readings? Publishing events?

46

So, what kind of world have we created in lieu of the kind of world that our cousins, the artists, live in, only a scant few blocks away, over in Chelsea? What kind of cashless economy is this? Let us put aside the academic economy and its near-relative, the world of grants and residencies, prizes and the like. What then are we seeking to delineate here? What is the question we are trying to answer? Is there an economy? And, if so, how is it denominated? But is that even first question we should be asking? Is there something more we are missing by asking the questions in this way? What, in the final respect, is the nature of our organization? Who are we, when we are seen in company, in sum? Is this a community at all? And, if so, how are we organized, how do we communicate with ourselves, how do we work?

47

¶ 18

What is the myth that causes us to fear the real world so? The myth that has us assume that we can’t cope? That the best of all possible worlds is the one in which we can write all day... and not cope? To not have to deal with the ‘real world’ ...at all, or hardly at all. That it is okay to have a crappy job... so that, for decades, we will be sure to have ‘enough’ time to write...

48

Are we so much better than the world around us, this corrupt, grubby world? This world where we try to avoid getting run over by Town Cars filled with morons wearing suits that cost more than we make in a month. Must we avoid inveigling ourselves in that kind of corruption? That world of compromise? Are we afraid? Afraid that we might not have the skills, or ability to compete with those we feel are not our equals? Is it competition itself?

49

So, when we say we cannot deal with the ‘politics’ of a place, a workplace, say — what are we saying? That we can’t deal with the duplicity or the shifting terms and conditions of the place or, is it that we fear that we just can’t interact with others on that level of complexity? We can’t or don’t want to have to put that much time and energy into that sort of thing, into having to deal with others? Do we think that we can’t deal with this? Don’t want to? Shouldn’t have to? Are we too good for all of that or do we really think that we aren’t good enough?

50

¶ 19

Which leads to that retreat. That stepping back. That consolation which writing provides. This is something we are good at. Which no one can take away. Which leads to other problems, all too often.

51

If we are most alive when we are writing, if we can sit and say to ourselves, this is what we are here for, this is why we are, say, placed upon this earth, to do this work, when I am doing this I am making use of all of my faculties, all of my powers, I am on fire, I am finally alive, here doing what I was put on earth to do, in this room, in this apartment in this corner of Kings County, if this what I am meant to do then everything that I have done, read, trained myself toward has led me to this very moment. When I sit and write, and do this work which the world needs so badly, which no one else in the world can do, why is it so much better to do it with the aid of some sort of stimulant? Or is it? What drives so many of us, or some of us, or perhaps all of us to, to say we need to put something extra in our bodies when we sit down to work?

52

Is it that we are just trying to heighten our powers, increase our ability to focus, to apply ourselves? To facilitate the flow, to free or unblock or engage or disengage, is that why we do, or did, put those things in our bodies? Alternatively, if writing gives us so much pleasure sober or straight, how much more pleasure, or so the argument could go, can it give us with the aid of one or another sort of substance?

53

Or, could it be that there might be some correlation between this writing, and its ability to enable us to block out the very world that we are trying to ‘reach?’ And could that such ‘blocking out’ is instrumental to the activity itself? We need to ‘blot out’ the world in order to save it? That is, to focus in upon it. And that selfsame fear that says that, pace above, we cannot deal with so many dimensions of the real world, like having a real job, conspires to turn poetry into a retreat, a shelter. Do we write poems because we don’t or can’t do those other things? And, by extension when we sit and drink or smoke or do other things might it not be that we are in fact retreating further?

54

But what about that veritable, undeniable flush of wellbeing, the racing of the pulse that the act of writing produces, and which writing itself may very well be intended to produce. The pleasure of it.

55

And abandon? ...What about Abandon’s vital, historical, central role in our activity? Its honored place in our profession’s armamentarium? If one stipulates that part of our job is in fact to look upon this world from a certain distance and cast it in a new light, can not one also argue that such work requires a degree of untethering, of unshackling? And some vehicle of abandon — somehow or anyhow achieved is, in or of itself, required? How we achieve same, then, can be said to beg the question. We cannot always be sober, can we?

56

The poets have their gods and their lights, and their honored traditions. The fruits of the vine, for example, are said to be counted among them. And, we can aver, so have they forever been. And forever shall. But so is, and was, and likely will be — alcoholism, and the other addictions.

57

¶ 20

Sensation and abandon

58

Nonetheless, can it be that it is in our interest to embrace abandon more than others, than those so-called ‘civilians,’ say? Because we are that much more in the throes of ‘sensation.’ That is, is it because we ‘feel’ so much, and therefore we are then so much more sensitive, that we need to free, lose, anesthetize ourselves so much more than people who aren’t so... so what? ...tuned in, perhaps, or receptive, or creative? Can any of us actually mouth such a line with a straight face? How much bad behavior has been excused under this tattered rag of what passes for argument?

59

¶ 21

To what degree should this indulgence, this ‘gimme,’ this lifestyle Mulligan, apply for everyone, not just poets — everyone who has or has to have a job? And then, who does that exclude?

60

If we have an inalienable right to pursue Abandon (and who doesn’t) who should be excluded from the class of creative types? Or, who are those who are under or so much pressure from the constraints or contradictions inherent in the way they have to live that they might not also have the same right to lose themselves... to embrace irresponsibility? Who, in other words, doesn’t get a free pass... to mess up, to get messed up, to wake us up as they kick over garbage cans and throw up into the gutter on Essex Street?

61

¶ 22

There is an eternal war against laziness, forever being lost.

62

There seems to be a relationship between sloth and creation. There is the allure, and virtue, of entropy. Of course, many would argue that the cousin of abandon is indeed sloth, as the cousin of application is obsession. Obsession manifests itself in a phenomenon of which we are all too familiar in our world: writing too much. And how vital, ever-present is sloth in how we define ourselves? Not only as a badge of honor particular to our calling, with a long and honorable role in our history, but also might it not have a more central role, as the noble Max B famously remarked (more fully cited below)? Could it be that some of this sort of ‘time’ is necessary, for us to spend, to expend? So that we can properly execute our role in life?

63

If that is in fact the case, might that then go to the argument that the copy-shop on Bleecker Street lifestyle, e.g. the “mental-sloth enabling” lifestyle, that is to say the entirely unchallenging life style might in the final respect prove to be a rational, appropriate, altogether proper choice for at least some of us?

64

¶ 23

Should it not therefore be so much easier to be a poet than, say, a painter? If part or all of our argument is that we are men, or women, essentially like every other man or woman — seeing the world and reacting thusly, when we make or create what we do, does it not make it simpler, and cleaner, and more appropriate that in every way except in the act of making what we make, we are indeed just like everyone else?

65

Why do we think we should be held up for approbation because of this one thing–no matter how heroic we believe it is? Or perhaps does it in fact not make us different or better than anyone else at all?

66

And, does not our obscurity oblige us to live in two worlds — separate but related, in a way that many of our peers, say, in the art world do not? They may not be obliged to deal with these issues. We walk the streets of that other world, the everyday world of regular men and women. Unseen, unrecognized. It makes it easier to suss it all out, does it not? It is the source, after all, and destination of our work, is it not? We live in that world, the world of grimy sneaker stores on Broadway, and yet we do not.

67

As artists we can dwell in it — that world, this world, and we must, with a thoroughgoingness that others can’t — because we have no options. We are obliged to live this greater, or worse, one. And, in theory at least, we can pass with the greatest fluidity and return to our other world, the one in which our art lives, and reigns.

68

¶ 24

But, we do know, we feel it in our bones, that creating, that being a maker, is in fact the highest form of being. We just know it. That is why we know that we are most alive, most human — perhaps the only time we are fully alive — when we are engaged in this work.

69

At the same time we must remind ourselves that we are no better, in any way, than the next man, the next woman. That the utility of our role is no more central to our species than any other. Yet, we know that what we do is so important that the world depends upon us, even though it thinks it can ignore us. But no definition of humanity can be deemed complete without us. It doesn’t matter if no one reads us except us.

70

¶ 25

As Max Beerbohm said, “the only problem with being a poet is figuring out what to do with the other twenty-three hours of the day.”

— Michael Gottlieb, 24 January 2008