| Jacket 36 — Late 2008 | Jacket 36 Contents page | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 18 printed pages long. It is copyright © Ian Davidson and Jacket magazine 2008.See our [»»] Copyright notice. The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/36/davidson-ohara-places.shtml

Paragraph 1

Reading through The Collected Poems of Frank O’Hara (CP), I am struck by the way the poems produce a variety of places (and the connections between them) from which the speaking subject can critique the normative assumptions of mainstream American culture. The places in his poems are rarely described in detail as if they existed beforehand and he simply inhabited them. His activities produce them as they also produce the speaking and writing subject of the poems and explore relationships between the body and the rural and urban landscape.

2

The emphasis on the material qualities of a place in his poems does not provide stability for O’Hara, for whom places are capable of acute and sudden change. The scenes he creates in poems such as ‘The Day Lady Died’ (CP, 325) where a lunchtime walk and shopping trip become an elegy for Billie Holiday, demonstrate that although a place may be familiar, it is never normal. It is always reproduced by each new visit. Places exist within a state of change, changes that he often welcomes, yet that can also threaten, and changes that simultaneously produce new and different places, and selves[1].

Frank O’Hara, center

3

Following the trajectory his work in the Collected Poems from the earliest work to his final poems, it is possible to identify the places in his poetry as existing within a series of geographical or physical levels which he moves between, levels which may physically exist but which he also uses metaphorically. They range from the underground to the clear blue sky, yet with many points in between, and indicate degrees of liberty, marginalisation and exclusion and oppression and threat. They are levels in which he can reveal himself, in which he can hide and in which he can change perspective. As well as the ‘underground’, his topography includes ground level, usually typified by grass or leaves, street level, a panoramic view from the tops of mountains or buildings and a ‘bird’s eye’ view, sometimes from an aeroplane and at others from out of a clear blue sky.

4

Within these levels other variations exist; between the rural and the urban[2], between light and dark, inside and outside and America and Europe. Levels also contain within them an implicit notion of connection. He knows of the existence of different levels because of being able to move between them, and that they provide different perspectives. Rather than existing on the surface of the city, a more normal way of representing the spatial relationships in O’Hara’s best-known poems, he moves between a series of heights and depths, just as the chatty and often apparently inconsequential surfaces of his poems have within them hidden layers, and routes to deeper meanings, to use a somewhat clichéd expression from mid-twentieth-century psychoanalysis.

5

O’Hara uses these levels, and the connections between them, as ways of increasing the potential significance of his activities and the places they produce. The sky, for example, often takes on an important role in linking the rural and the urban. Clouds, both meteorological and those that come from the smoke of cigarettes, can obscure the sky, and the screen in the movie house and can provide cover for an over-illuminating moon. His shifting perspectives reflect the movement of a body in space as it changes direction, has a limited view or is facing one way or the other. Space for O’Hara is often embodied space; it doesn’t exist if he isn’t in it or can’t imagine himself in it, yet the speed of movement of his poems and the speaking subject in them, means that a lot of ground can still be covered.

6

His depiction of a series of levels is, though, more than simply a quest for movement or variety. The real and imagined topography often represents marginalized spaces in American geography and culture to which people are pushed (like the Negro taxi driver in ‘Rhapsody’ discussed later in the essay). They are places outside the range of social norms that he simultaneously chooses and is forced to inhabit, in locations such as mountain tops, parks at night time, lying beneath the leaves, darkened movie houses and subways and tunnels. The perspectives he holds are more often multiple rather than singular, and a particular place can be simultaneously desired and feared, and can be revealing and concealed. Nor are his perspectives consistent over time, and working through the Collected Poems, different poems produce different representations of his rural childhood and his problematic relationship with the countryside and his family in his earlier work, his relationships to the art world and with New York in the mid to late 1950s and to the increasingly abstracted and mediated productions of ‘postmodern’ American and global culture in his last poems from the 1960s.

7

The early poems combine the imagined and conceptual spaces of the literary pastoral and anti-pastoral with the materiality of a countryside produced through the activities of a rural childhood and adolescence, themes he would return to in ‘In Memory of My Feelings’ and ‘Ode to Michael Goldberg’s Birth’. In ‘Oranges: 12 Pastorals’ (CP 5—9), Tess is ‘amidst the thorny hay, her new born shredded by the ravenous cutter bar’. The field becomes the sky, and is ‘dotted with excremental discs, wheeling in interplanetary green’ and with ‘stars’. These more abstract descriptions become located via the fleshy body and its relationship to its environment when, in an evocation to Pan, the speaking subject reveals that: ‘my reclining bones have made a profound pattern on the earth’. By the third ‘Pastoral’ we know that although ‘I have lain screaming for five days’ the rural still retains the restorative qualities of the pastoral: ‘There is water flowing underneath. The rain is making a river to wash | my buttocks’.

8

The poem then switches to a meditation on the relationship between inside and outside of domestic space: ‘once in bed we thrashed about’, and the ‘storm blew the window in’. The social pressure from the outside is stronger than the environment that can be created inside and the window is blown ‘in’, not out. In highly charged language[3] O’Hara continues to introduce many of the topographical references that will feature in later poems. An eagle takes him to a ‘pinnacle’, a place of self-awareness and self-reflection and where ‘you have known what I lacked’. Climbing the mountain, is a quest for clarity, and ‘the landscape behind us’ is a confusion of different figures. The mountain comes from the geographical and physical topography of his childhood; it also metaphorically describes a difficult task that needs to be completed and, more obscurely, refers to a mountain of flesh.[4]

9

In Pastoral 6 ‘we’ lie on the floor in semi darkness and: ‘in the fields we shall lie down together inside a bush and play secretly’. Landscape and human figures begin to merge in a description of an idyllic encounter ‘under the mist’ where both the threat from above and below is countered and: ‘we need not fear the sound of wings or the sneak of tangled roots’; his ‘passport’ into this world illustrated by ‘a portrait of the poet wrapped in jungle leaves airy on vines’. It is through poetry that the place free from fear and free of social pressures is produced. This early poem begins to bring together the speaking subject as poet and as lover in a sexualised landscape with a series of topographical levels.

10

The poems also become marginalized literary spaces in which O’Hara can explore ways that the speaking and writing subject might know things about themselves. The poem, through the use of the pastoral, is a place of reflection, of trying to work out what things might mean by locating them in an imagined space. The structure of the poem offers the possibility of embodied presence, and in Pastoral 12: ‘By direction we return to our fulfilling world, we are | back in the poem’. The poem provides a space that is ‘fulfilling’ and where potential can be realised, and where the incoherence of the real world and its shifting planes of experience can be experienced as well as reflected on. After a section towards the end of the poem in which the countryside turns gothic nightmare he exclaims: ‘This is the miracle: that our elegant invention the natural world redeems by filth’. The poem, the ‘elegant invention’, is redeemed not by the beauty of nature, but by its ‘filth’. It is a poem about being in the countryside, but it is also a poem about being in the poem, a place of redemption that, by extension, combines the relationship between the poem and the other places it produces.

11

O’Hara, despite his frequently quoted phrase from ‘Meditations in an Emergency’ that he can’t even enjoy a blade of grass unless he knows there’s a ‘subway handy’ (CP 197), has a country person’s eye for natural detail. In ‘The spoils of Grafton’ (CP 26) the ‘drain pipe | screams with moonlight, when the moon comes out’ and the ‘wind | swoops down the hill without | skis, driving mice into the cellar.’ The stars frequently become both stars in a clear sky and people in a city. Through this frequently used image O’Hara recalls his youth in the countryside, where walks under the stars are sometimes given a sexual intent, and refers ironically to the celebrity status of a dressy urban population, the idea of a film ‘star’ and to the slang term used to indicate someone who thinks they are someone important or successful. In a reverse image he sees the stars on the city streets and in the cafes and bars from above, stars that are as numerous and as anonymous as stars in the rural sky. The sky, and by association the stars in it, becomes a place that can actually or potentially transcend the messiness of the everyday in both rural and urban locations, in the same way that the anonymity of the human ‘stars’ in the city provide freedom from the familiarity of a rural existence.

12

He sustains the relationship between earth and sky and between urban and rural in other poems. In ‘A note to Harold Fondren’ (CP 34), the ‘sky’ is like our ‘thoughts’ that ‘move | steadily over a … moral landscape’. The ‘earth’, by contrast, is described in ‘A Poem in Envy of Cavalcanti’ (CP 35) as ‘my personal mess’. Yet mess is not always personal, but often caused by the activities of others who intrude on private practices. In ‘The Lover’ (CP 45—46) he describes a rural scene where a lone figure waits unsuccessfully for a lover to arrive, although uses the Italian word Andiamo (let’s go) to indicate that this is not your usual rural America. The moon, often either obscured by clouds or the object that illuminates a scene better kept from the light, becomes ‘a nasty little lemon’ which is personified as racist and a ‘queer basher’. The moon, or its agents, wants to ‘throttle’ a ‘swan’ and the word swan becomes a metaphor, for the beauty of nature, and the acronym of a woman who has, in racist slang, ‘Slept With A Nigger’ and transgressed social norms. The reason for the lone lover’s isolation is fear and sexual desire: ‘We too are worried. || He is a man like us, erect.’ Escape for O’Hara is behind or under the clouds, under the leaves or in the sky.

13

‘Easter’ (CP 96—100), written some three years after ‘Oranges’, presents a similarly sexualised landscape, but one in which the body parts are more frequently named and sexual acts more directly referred to. The prose poetry of ‘Oranges’ is replaced by lines which stop short at every ending, even those in which the syntax runs on, giving the poem the layered dynamic of a list of images which keep piling up, one on top of the other. The abstractions, of which there are many, and the coded language of a homosexual subculture, which runs through the poem, are both located through a range of real and imagined geographical and cultural locations and levels and through an embodied presence to which the poem always returns. Body and landscape are linked in an early line where: ‘The perforated mountains of my saliva leaves cities awash’; a connection that continues in the: ‘glassy towns fucked by Yaks’ and a ‘world’ that: ‘strips down and rouges up’. The action takes place on a ship, which ‘shoves off into the heady oceans of love’, and there is a: ‘princess whose mouth founders in the sun and who is drowned by honey in a ‘green valley’.

14

These varied relationships between body, landscape and sexuality and the levels they both choose and are forced to inhabit, are more fully explored in a longer poem from 1955, ‘In Memory of my Feelings’ (CP 252—7). The poem shifts between ‘the cool skies’, a position from which the speaking subject can ‘gaze on the imponderable world with the simple identification | of my colleagues the mountains’ and the ‘track’ where this simple identification becomes fractured as ‘one of me | rushes to window 13 and one of me raises his whip and one of me | flutters up from the centre of the track amidst the pink flamingos.’ The ‘earth’ becomes a place of ‘terror’, and his position in it is ‘underneath its leaves as the hunter crackles and pants’. In a mixture of movie iconography and an image of a hunter, ‘animal death whips out its flashlight’, recalling his earlier poem ‘In the Movies’ (CP 206—9) where he calls out both in fear and longing: ‘Ushers! ushers! | do you seek me with your lithe flashlights’, and earlier still in the poem ‘A Pastoral Dialogue’ (CP 60) where he asks: ‘Should my penis through dangerous air | move up, would you accept it like a torch?’ O’Hara refuses to allow any definitions or metaphoric relationships to settle with any consistency, and the flashlight is both penis and thereby a reference to ‘flashing’, and the light that reveals what happens in the dark.

15

The landscape becomes the body and the body becomes the landscape. It is possible to see both from the inside and the outside, and to be either within or on the surface of both. As he says in ‘Meditations in an Emergency’ (CP 197—8): ‘My eyes are vague blue, like the sky, and change all the time; they are indiscriminate, entirely specific and disloyal, so that no one trusts me. I am always looking away.’ While O’Hara is often apparently describing an everyday event or object in everyday language both his perception and ours keep shifting around, seeing it from different perspectives and in different contexts. He is not, however, simply demonstrating that things can be looked at from different perspectives, or that this is desirable, but is asserting the impossibility of seeing something from one perspective. O’Hara’s aim is to both move quickly, so that he is as difficult to pin down as the objects and places he describes, and to lose himself, an act which he is able to do more effectively in the urban spaces of New York than in the rural locations of his upbringing.

16

A number of levels begin to cluster together in ‘In Memory of My Feelings’ and become interrelated; the earth with it’s carpet of leaves and bodies under the leaves, the movies and the flashlight, the moon that illuminates the scene with benign and wicked intent and a sky full of stars that reflect the people on the ground. O’Hara repeatedly compares himself to a hunted animal, turning rural idyll into war zone. His entry into the urban spaces, a process that happens over a period of time, gives him a freedom that he can’t find in the more threatening landscape of rural America. He says in ‘Meditations in an Emergency’ (CP 197) that ‘I have never clogged myself with praises of pastoral life’, and in the next poem in the Collected Poems, ‘To the Mountains in New York’ (CP 198—200), the apparently contradictory title characterises the freedom he feels in the city:

17

Yes! Yes! Yes! I’ve decided

I’m letting my flock run around,

I’m dropping my pastoral pretensions!

18

Echoing the meaning, but not the darker tone or more ambivalent meaning of ‘Homosexuality’, the poem begins with an assertion of a freedom that is reflected in his descriptions of himself as a ‘slow white horse’. While the scene still recalls the rural America of his youth in the ‘pine trees and clouds’, it is ‘wandering away’ from him and he now walks ‘watching, tripping’ and ‘alleys | open and fall around me’. It is a place where anonymous sexual behaviour is in the fabric of the walls and the ‘nobility | oblige invisible bayonets.’ He becomes ‘lost’ and with ‘no way back to the houses | filled with dirt’ yet the poem ends in a somewhat unconvincing turn to ‘the earth’ and an elegy for an unnamed lover who, having actually or metaphorically died, is placed in a ‘funeral ‘barque’ and its sails filled with ‘the tempestuous blue of my eyes’.

19

These two poems do represent a kind of turning point in the Collected Poems. From here onwards, although it doesn’t by any means disappear, the rural imagery becomes less frequent and the urban predominates. The action in the poem more frequently takes place at street level and in daylight, yet it is a street level that is in a hierarchy of levels. The ‘underground’, often symbolised as the subway, becomes more pronounced as a place of transgression, although a ground level, often with leaves and always at night, is also retained.

20

‘Rhapsody’ (CP 325—6), written in 1959, does find O’Hara firmly located in New York. He moves between the underground, the level of the street and various perspectives from above. ‘515 Madison Avenue’, the opening line of the poem, is by association a ‘door to heaven’ and a ‘portal’ that could provide entry to ‘stopped realities and eternal licentiousness’. The doorway links inside and outside and ‘everywhere love is breathing draftily’ and everybody, the 8,000,000s of the population of the city frequently evoked by O’Hara, become potentially involved. From moving between inside of the building and the street, the speaking subject of the poem goes underground, thinking of the tunnels through which people are linked. In some ways, as in many O’Hara poems, the imagery is implicitly and explicitly sexual. The doorway provides ‘entry’ to the ‘tunnel’, and the tunnels, like the holes in the skin through which we communicate, are what link the population. This is an image he is to use again in ‘You are gorgeous and I’m coming’ (CP 331) where the ‘past’, in ‘falling away as an acceleration of nerves … | aims its aggregating force like the Metro towards a realm of encircling travel’.

21

The imagery in ‘Rhapsody’ is also, and at the same time, of an interconnected population, and not just two people. The political content of much of the rest of the poem, and the class awareness of the conversation with the cab driver about the price of property, and the anger in the fourth stanza at when you have to ‘run the gauntlet’, mean that the poem combines the two readings of New York and, by extension, America, as places of sexual possibility, and as places of potential human connection. By going ‘underground’, O’Hara has discovered both potential sexual opportunities and opportunities for more politicised connections.

22

The ‘summit’ in the first line of the second stanza, the opposite of the tunnels, is the place where all aims are clear, an illusory place for O’Hara in this poem, but one that he always aspires to. It is the place of the earlier poem ‘On a Mountain’ (CP 243—4), where after ‘rattling leaves’ he says ‘Here is where I | have come, so high | to find this true’. In ‘Ode to Michael Goldberg (‘s Birth and Other Births)’ (CP 290—8) he gives an autobiographical origin to the idea of rising above the everyday activity of the street.

23

Up on the mountainous hill

behind the confusing house

where I lived I went each

day after school and some nights

…

… there

the wind sounded exactly like

Stravinsky

I first recognised art

as wildness and it seemed right

I mean rite, to me

Climbing the water tower I’d

look out for hours in wind

and the world seemed rounder

and fiercer and I was happier

because I wasn’t scared of falling off

24

This lucid and extended piece of autobiography, and Brad Gooch gives further details of the geographical location of the water tower in City Poet, is in stark contrast to the muddied imagery of the earlier pastoral poems. The speaking subject of ‘Rhapsody’ echoes this clarity, albeit from an adult perspective, when he says he has ‘a sight of Manhatta in the towering needle’ and has the ‘multi faceted insight of the fly in the stringless labyrinth’. The panorama of the countryside is replaced with the labyrinth of the city, but a labyrinth that is nothing like a cobweb in which the fly is stuck but one that is ‘stringless’ and can be moved through with ease.

25

Yet the ease of passage that is apparent in a poem such as ‘The Day Lady Died’ (325), although it only leads him to the elegiac moment in the ‘5 SPOT’, is lost in ‘Rhapsody’ when he has to ‘run the gauntlet’. His response is to fight back, and in a moment that combines expectoration and ejaculation, to ‘spit like Niagra Falls on everybody’, a tension that is more apparent when race meets money, and the ‘Niger joins the Gulf of Guinea’. Madison Avenue is still off bounds to the taxi driver, a place where ‘you’ve never spent any time and the stores eat up light’.

26

The poem, as well as being one about levels, becomes more explicitly about connections. Moving between levels makes new connections between ideas and people, and moving through connections creates new levels. The sexual attraction of individuals is one way of making connections, but does not detract from the connections of an inter-racial or class-consciousness; both happen simultaneously. The ‘love’ that ‘is breathing draftily’ is a sexual love and a non-sexual love, and O’Hara’s championing of black rights comes from a notion of love that barely distinguishes between them. Joe LeSueur talks about ‘the “thing” that O’Hara had for black men’ in his digression on the poem ‘At the Old Place’ (CP 223), and goes on to say that ‘it was another way of saying that he was drawn to all kinds of racial, ethnic and physical types. Still, his compassion for blacks was exceptional, since it encompassed affection, compassion, and a genuine interest in them along with sexual desire … ’ (LeSueur 57). Gooch is very clear about the way that O’Hara combines love and sex in a number of ways in his relationships with men and women, including Bunny Laing, Grace Hartigan, Larry Rivers and Joe LeSueur.

27

While O’Hara’s anxieties (and delights) over the depersonalised acts of cruising and sex with strangers are often expressed in the earlier poems, ‘Rhapsody’ is written in 1959, some years after Joe LeSueur describes O’Hara’s ‘conversion’ in ‘the fall of 1955, about a year and a half after he wrote ‘Homosexuality.’ After going with O’Hara to see a performance by the poet Chester Kallman, in which Kallman described sexual activity with a stranger in a particularly lascivious way, LeSueur ‘noticed that Frank no longer engaged in wild sex exploits’. According to Le Sueur, O’Hara says, ‘I thought about it a lot, about the way Chester talked, and decided I didn’t want to be like that.’ The ‘conversion’ is reported as ‘immediate and complete’ and that his ‘friends … were henceforth his sole sex partners’ (LeSueur 40).

28

In his conversation with the Negro cab driver in ‘Rhapsody’ O’Hara can therefore simultaneously reflect on ‘the challenge of racial attractions’ and connect to the sexual possibilities of all of New York, yet decline both. They are also racial attractions that can lead ‘into the lynch’, a word that sounds like ‘clinch’ when linked to ‘dear friends’, but is a reference to lynching, a possible consequence of inter-racial sex for the non-white. O’Hara switches levels and tries to seek out the ‘summit where all aims are clear’, although finds he is still coughing ‘lightly in the smog of desire’. His vision lacks clarity and the smog makes his eyes water, eyes which are only ‘achingly imitating the true blue’, a true blue of the sky and of an unproblematic homosexuality. O’Hara therefore conflates the prejudice against homosexuality and racial prejudice, particularly in mixed relationships. Through reported conversation that maintains the light, chatty surface of the poem, he comments on the housing situation for blacks in New York, and the ways their bodily functions are circumscribed by shoddily built apartments: ‘where you can’t walk across the floor after 10 at night | not even to pee, cause it keeps them awake downstairs’, a comment which will provide him, sarcastically, with ‘a little supper club conversation for the mill of the gods.’

29

The implied addressee of the earlier stanzas becomes ‘you’, the taxi driver, who (in a phrase echoing Christ’s ‘the poor are always with you’) was ‘there always and know all about these things’. This suffering is endured passively, but not without awareness, and the taxi driver is described ‘as indifferent as an encyclopaedia with your calm brown eyes.’ The ‘you’ in O’Hara’s poem is often explicitly the lover; in this case it is the Negro taxi driver. O’Hara uses the same tone and affectionate language for both expressing sexual love and desire and a sense of empathy, although the moment of political clarity passes as O’Hara runs in references to Victoria Falls, where water falls between levels, and the ‘beautiful urban fountains of Madrid’ where water is jetted into the sky[5]. The you, the taxi driver, returns in the last two lines of this stanza as the figure of the outsider, passing through Madison Avenue in the early morning and seeing the stores both lit up and ‘eat[ing] up light’, but without entering them.

30

The last stanza is an extended meditation on American culture. In an ecological turn on ‘the stores eat up light’, the nourishment provided by ‘this mountainous island’ becomes rancid. Mountainous, as I discuss earlier, is for O’Hara, a potential condition of reflection, understanding and escape. This island is also Manhattan and it’s mountainous qualities human ones who are ‘coming’, and whose very physicality will drive O’Hara, now the figure of the aesthete ‘sorting his poems in a hammock on St Mark’s place’, to a place of holiness, which may be Tibet. The physical ‘bliss of American death’, of which he is a part as America kills him and he kills America, is both the reason for his writing and being in America. and his disembodied release from it as a ‘holy one’.

31

In ‘Rhapsody’ the levels of activity explicitly become politicised as a series of vertical connections, between the tunnels and the surface and the summit, lateral connections between one side of the door and the other, social connections between black and white, poor and rich (O’Hara carries the story of the cab driver to the supper club), and conceptual connections between embodied and ethereal. Yet O’Hara never lets these binary connections become a stable condition, restlessly reconnecting or divorcing black and rich, poor and white. O’Hara might be separated by race and class from the Negro taxi driver but he is also connected to him by human love. The reference to Tibet sustains his idea of an interconnected world, and O’Hara never lets us forget in the numerous references to other countries and continents in his poems that America is not its own world of which New York is the capital (see my discussion of his ‘World’s Fair’ poem later in this essay). O’Hara is producing radical local spaces through connecting with other individuals in New York, yet linking those local spaces to the global through international cultural connections and notions of empire.

32

In his early, more rural poems the shifts to different levels under the leaves, to the tops of mountains or into the blue, are strategies for survival for O’Hara as he tries to escape the attentions of a threatening culture. The more heterogenous and culturally diverse urban population, while not without threat, allows O’Hara to use the different levels as more than a means of escape. In ‘Adieu to Norman, Bonjour to Joan and Jean-Paul’ (CP 328—9) he is able to transcend his physicality by ‘flying over Paris et ses environs’, and in ‘Joe’s Jacket’ (CP 329—30) he can ‘see life as a penetrable landscape lit from above’. From this ‘mid-career’ work, which finds O’Hara most at ease with the places he produces, I want to move to the final sequence of ten poems, probably written around 1964, and provisionally entitled by O’Hara as ‘The End of the Far West’ (CP 478—86). These poems are visually characterised by a broken left hand margin and a conversational style in which the speaking subject is constantly changing. In other words the conversation is not, as with many of O’Hara’s so called ‘I do this and I do that poems’, between the speaking subject of the poem and a specific or general reader, but between different voices within the poem.

33

As well as failing to identify a consistent speaking subject, this final sequence of poems has no location, rural, urban or in between, but exists in the spaces produced by the mass media, and demonstrates an important formal shift in his work and his relationship to United States culture. They are poems in which ‘There’s nobody at the controls!’ (CP 483); the lyric self has dropped away, leaving poems constructed out of a range of words and phrases often with direct reference to films, tv or radio shows, and at times, apparently spoken by characters.[6] He develops poetic procedures where he can use urban ephemera without placing them in the sequence of a ‘walk’. This is not without loss, and the visceral intensity of his earlier work and the sense of internal struggle that characterizes it, and the irresistible charm of the speaking subject of Lunch Poems and Love Poems, do give way to a more ‘knowing’ style.

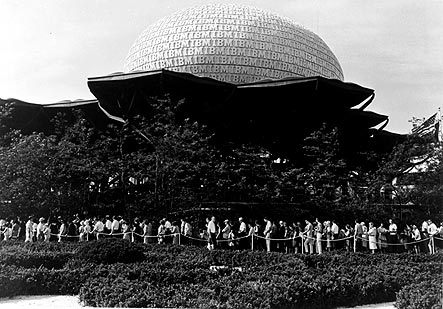

The IBM Pavilion at the 1964–65 New York World's Fair covered 54,038 square feet (1.2 acres) in Flushing Meadow, N.Y. Designed by Charles Eames and Eero Saarinen Associates, the pavilion created the effect of a covered garden, with all exhibits in the open beneath a grove of 45, 32-feet high, man-made steel trees. The pavilion was divided into six sections: The “Information Machine”, a 90-foot-high main theater with multiple screen projection; pentagon theaters, where puppet-like devices explained the workings of data processing systems; computer applications area; probability machine; scholar’s walk; and a 4,500-square-foot administration building. (VV2085)(courtesy IBM)

34

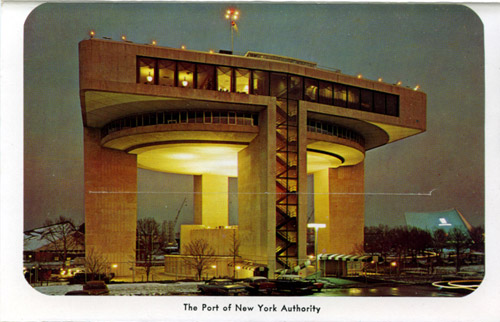

The poems provide a satirical commentary on United States culture; on the ideals of the American ‘West’ in ‘At the Bottom of the Dump there’s some sort of Bugle’, ‘The Green Hornet’ and ‘The Jade Madonna’, on war in ‘Enemy Planes Approaching’ and on human relationships in ‘Should We legalise Abortion’ and ‘The Bird Cage Theatre’. An embodied presence in the poems, an important element in O’Hara’s work, has been replaced by disembodied and mediated representations of the present. In the poem ‘Here in New York we are Having a Lot Of Trouble with The World’s Fair’ he seems to echo Guy Debord from The Society of the Spectacle in the ways in which experience can no longer directly be directly grasped, but is mediated via equipment which itself says something about the messages it transmits. The 1964 World Fair, despite its internationalist message of ‘Peace through Understanding’ and the universality of its dedication to ‘Man’s Achievement on a Shrinking Globe in an Expanding Universe’, became more of a showcase for American corporate culture. As a consequence the symbol of the fair, a twelve story high representation of the earth called a ‘unisphere’, seems to represent a single dominant perspective rather than the multiple perspectives of O’Hara’s poetry. The levels I identified in previous work become flattened out on the ‘multi-screens of the IBM pavilion’ (CP 481). Many of the exhibits, and four of them were by Disney, featured ‘rides’ through animated landscapes in armchairs or replica cars.

Postcard of the Port Authority pavilion at the 1964 World’s Fair

35

In his 1980 essay “Within the Context of No Context,” George W.S. Trow, who had worked at the fair, wrote: ‘What was the Fair? It was the world of television but taken seriously… At the Fair, one could see the world of television impersonating the world of history. It was the world of television, but they wouldn’t let you in on the joke.’ Alice Notley in her essay ‘O’Hara in the Nineties’ (Notley 3—14) refers to the poems in ‘The End of the Far West’ as being written ‘under the influence of television and its deadly flat diction’ (Notley 12). There is a sense that the ‘movies’ so important for O’Hara and his generation, where in the solitary darkness of a place the image from a single source of light was watched from a fixed perspective at a pace dictated by the film coming off the reel, is replaced by the more controllable image of the television, with the viewer’s ability to change channels and stop and turn programmes on and off in their own domestic space, and to have multiple simultaneous screens. The poems in ‘The End of the Far West’ do sometimes seem as if they are the result of ‘channel hopping’ and a record of the resulting coincidences and juxtapositions, yet they also combine aspects from different genres in order to enter into an intertextual dialogue with mediated representations.

36

The poem ‘Here in New York we’re having a lot of trouble with the World’s Fair’ (CP 480—1) begins with three apparently unconnected sentences that sound as if they come from three different scenes of a gangster movie or movies. The tone is ‘hard boiled’, and each sentence ends abruptly, causing the next sentence to start afresh. The connection between the sentences is the second person pronoun ‘you’, a word with a different signifier in each of the first two sentences:

37

A million guys in this

town and you have to shoot

the Crime Commissioner.

You loved it tonight

Because for the first time the audience treated you

like a lady, a real lady.

Well, I guess that squares me

with both of you. (CP 480—1)

38

The stanza contains within it elements that hold it apart as well as a final sentence that contains a resolution, as if both of ‘you’ from the first two sentences have been given their allocation in the poem. The result of that resolution is a shift from the second person pronoun to the first. ‘Me’ is squared, that is closed off or complete. It is multiplied by itself in order to provide a complete unit.

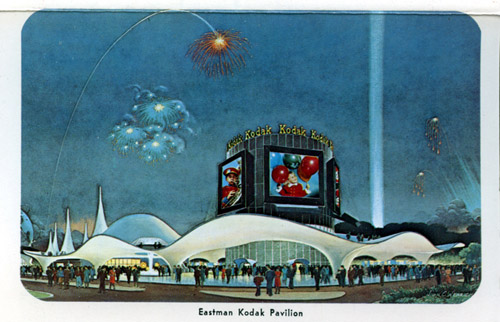

Postcard of the Kodak pavilion

39

At the start of the second stanza the second person is more general and given instructions that might relate both to the ‘rides’ at the World’s Fair and to sexual activity through the phrase ‘pull out’, the direction to ‘tense your muscles from head to toes’ and the reference to ‘black out’. The poem then shifts to the first person plural pronoun ‘we’, and a situation whereby, although things didn’t go quite right, they are ‘on the right track’, a reference both to the connection between the people named in the ‘we’, and the tracks that carried a passive audience around the World’s Fair. His ironic aside, that ‘next time we better try ski jumping’, collects together references to skiing, a free way of individually moving across the snow in any direction with little friction as compared to the ‘tracks’ of the World’s Fair, and to ‘ski jumping’ as a reference to a process of mutual masturbation. This continues the dual reference to ‘pull out’, as relating to penetrative sex and to the rides at the world fair, and the reference to orgasm in ‘no blackout.’

40

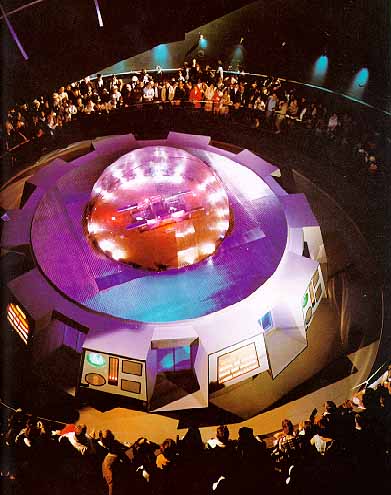

In these few lines O’Hara weaves together a compelling critique of the isolating individualism of the World’s Fair, and the connectedness of a sexual relationship. Yet O’Hara doesn’t let the poem rest here, but continues to shift around within those very terms he uses to destabilize the certainties of corporate America and its relationship to the world. The high technology of the Fair[7] is now given to the ‘Negro’, who can cruise ‘over the Fair in his fan-jet plane’, which, if it ‘ran out of fuel’, and presumably crashed into the Fair, would be a way for the ‘World’ to ‘really learn something about the affluent society.’ The promise of technology is only temporary. The Negro may be elevated for a while but would soon crash, exposing the superficial nature of the alternative ‘realities’ presented on the ‘multiscreens of the IBM pavilion’, and the act of ‘cruising’, would subvert the heterosexual norms produced by an homogenizing technology.

A model of nuclear fission at the World“s Fair

41

From elevating the ‘Negro’ into the air, O’Hara comes back to street level. There, despite the promise of the technology at the fair, ‘the stink of the fire hydrant drifts up | and rust | flows down the streets.’ Water and earth have defeated the simple mechanics of the fire hydrant, yet in ‘The Shakespeare Gardens’ the opposite seems to have occurred and the simultaneity of the ‘multiscreens’ seems to have produced ‘apple blossoms and apples simultaneously’. ‘We’might now refer to a couple or the more general population, but are ‘happy here’, a happiness that is not without cost. The subversion of the natural order, where apples follow apple blossom, is also reference to the ‘unnatural’ sexual relationships implied in ‘All right, | roll over.’ Yet that phrase again, weaves into itself references to ‘roll over’ as mugging, and to a passive consumption in which the populace lie down and roll over in front of the overwhelming technology.

42

In these late poems O’Hara appears, once again, to ‘let all the different bodies fall as they may’ (CP 498), as if the poem is the result of accident. And in part it is, and the overall structures rarely conform to any formal sense of logic, but within those accidents complex ideas are woven together to simultaneously provide a representation and a critique of American culture and its productions. This poem has ‘levels’ within it, from the ground in the street, from the gardens, to the sky and to the screens, but it also contains within itself a description and an analysis of the way those levels might be connected through human relationships. He is not naïve, nor is he seeking to eradicate difference, but he does, through the complex practices of this late poetry, create multi-level marginal spaces and connections between them that provide free space for the exploration of the ways in which people are held apart and the ways in which they might come together.

43

In a decade and a half, and from 1950–65, O’Hara moves from the country to the city, and from the city to the mediated spaces of global culture. The oppressive nature of a familiar rural society and the familiar places it produces is replaced by the illusion of freedom of a global economics, and in the poetry the more lyrically intense and anguished tones of his earlier work are replaced by the competing and mediated voices in ‘The End of the Far West’. The search for marginalized places in the countryside and in the earlier poems become replaced by a poetic in which the speaking subject is almost completely hidden in the dialogic folds of the later work. His interest in an actual and symbolic series of levels remains, but if in the earlier work these are frequently destabilized, in the later poems it is the movement towards stability that is undercut by shifts and new connections. The paratactic relationships between the short phrases, and the connections that he makes, become the places in which the speaking subject is located, rarely appearing on the surface of the poem.

44

His political concerns remain, but rather than being clarified, or simplified, become more complex as he develops a poetic through which they can be explored. His emphasis switches from the places of concealment in a material world within which he frequently ‘finds himself’ as a process of self discovery in marginal and hidden places, to poetry within which he becomes lost. This losing himself, however, only allows him an even greater flexibility in maintaining varieties of political perspectives without revealing himself, and a poetic in which the poem itself becomes the place in which he can hide from, yet also critique, American culture. What is revealed is a poet who, although he often works at a speed dictated by instinct, is no casual thinker, but can construct poems that speak of complex political concepts through both their form and the referential contexts from which the form is constructed.

Gooch, Brad. City Poet: The Life and Times of Frank O’Hara. New York: Knopf, 1993.

LeSueur, Joe. Digressions on some Poems by Frank O’Hara. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 2004.

Notley, Alice. Coming After. Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 2005.

O’Hara, Frank. Collected Poems. Berkley: University of California Press, 1995.

Chicago Press, 1998.

[1] Gooch in City Poet reports a conversation between William Weaver and O’Hara in which Weaver complains that ‘they were tearing down some brownstones.’ O’Hara is said to have replied: ‘Oh no, that’s the way New York is. You have to just keep tearing it down and building it up.’ (Gooch 218)

[2] Despite his fame as a ‘New York’ poet, or as his biographer Brad Gooch calls him, a ‘City Poet’, these places are not exclusively urban, and many of his earlier poems refer to the countryside where he was brought up, and the later poems, those written in the mid 1960s, are located in mediated and conceptualised global cultural spaces.

[3] John Ashbery describes the language in O’Hara’s early poems as ‘posturing’ in his introduction to the Collected Poems.

[4] ‘Mountain’ is a word that occurs throughout O’Hara’s work and seems to refer to both topographical features and people. I can only guess at it’s significance, and a potential relationship between the mountains in the landscape of his childhood, the mother figure and the idea of a ‘man mountain’.

[5] This political clarity is perhaps only matched by O’Hara reporting in ‘Personal Poem’ (335) that ‘Miles Davis was clubbed 12 | times last night outside BIRDLAND by a cop’.

[6] Film stars referenced in the poems include Joel McCrea and John Garfield, the radio play is The Green Hornet, there is reference to the Bird Cage Theatre in Tombstone, Western characters such as Wyatt Earp and Judge Hawkins and real events such as the World’s Fair of 1964.

[7] According to an account on Wikipedia the Fair included exhibits such as General Motors Corporation Futurama, a show in which visitors seated in moving armchairs glided past detailed scenery showing what life might be like in the "near-future,", that of the IBM Corporation, where a giant five hundred-seat grandstand was pushed by hydraulic rams high up into a rooftop theatre and a nine-screen film showed the workings of computer logic and that of the Bell System, a fifteen-minute ride in moving armchairs, depicted the history of communications in dioramas and film.

Ian Davidson

Ian Davidson has published As if Only (Exeter: Shearsman Books, 2007) and with Zoe Skoulding, Dark Wires (Sheffield: West House Books, 2007) among other books. A critical book, Ideas of Space in Contemporary Poetry, was published by Palgrave MacMillan in 2007. Another essay on Frank O’Hara, ‘Symbolism and Code in Frank O’Hara’s Early Poems’, in many ways a companion piece to this article, is forthcoming in Textual Practice. Ian Davidson lives in North Wales, Europe, and teaches literature and writing at the University of Wales, Bangor.