| Jacket 36 — Late 2008 | Jacket 36 Contents page | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 3 printed pages long. It is copyright © Al Filreis and Jacket magazine 2008.See our [»»] Copyright notice.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/36/oppen-filreis.shtml

Back to the George Oppen feature Contents list

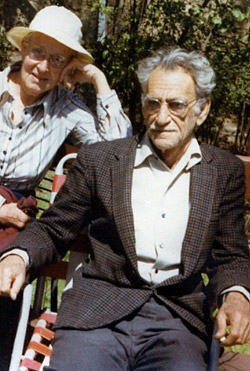

Mary Oppen, George Oppen, Swathmore, 1979. Photo Robert S. DuPlessis

paragraph 1

The blaze in George Oppen’s “Myth of the Blaze,” a great poem of war, sectarian ethics and personal guilt, is the burning bright of Blake’s “tyger” in the poem (and indeed spelled that way). Oppen’s sense of Blake’s “forests of the night”: the woods of the so-called Bulge in the horrendous battle of that name, the Rhineland campaign of winter 1944, the oblique tortured approach to the Rhine through France. “Did he who made the Lamb make thee?” This is a story of tiger and lamb.

2

The tiger of antifascism beyond theory: In November 1942 George Oppen suddenly moves to Detroit, thus triggering the lifting of his draft exemption, and off he goes to fight in — as it turns out — some of the war’s more horrific battles. He fought, in spite of fear, in spite of an inner pacifism (George the lamb here), and, most startlingly at the time, and perhaps most dangerously, in spite of the stated policy of the Communist Party of the United States (his CPUSA).

3

“Myth of the Blaze” is the most nuanced poetic expression I know of the impossible moment for the intellectual communist Left of the strange period — between September 1939 and June 1941 — when the leadership of the Party expected its members to support the Nazi-Soviet Pact by favoring peace over war, nonaggression over rapid armament, and to turn against the (finally) emergent (mostly) united front against fascism.

4

We know that George and Mary were most active in the party between 1936 and 1941, a span of time that of course include two years of suppressing their political impulses. Already aching with guilt over his failure to go to Spain in 1936 and ’37, George goes to war in ’42, his politics now once again aligned — tiger and lamb lying down together; fearful symmetry between Soviet Union and United States struck.

5

The “myth” in “Myth of the Blaze”: it is the imagination’s bright burning, the folklore of the alluring forest, just a myth. Bunk. Unreal, or un-Realist. “This crime,” in the poem, becomes: “This crime I will not recover / from” or “I will not recover / from that landscape it will be in my mind / it will fill my mind and this is horrible / dead bed.” Yet, on the contrary, the myth is real, as the imagination is the only thing. As one lies in a foxhole: he is bombarded by mortar fire, and wounded — all those he’s with are killed. More guilt. All he has, his mind and heart racing, are a lyric of Wyatt and “Rezi’s” (Reznikoff) “running thru my mind / in the destroyed (and guilty) Theatre of the War.” The blaze is real — the fire this time. The blaze is real and not a myth. The blaze — in Rezi’s poem about the blaze of the real in the imagination — is the myth. Guilt about thinking poems when the world is coming to an end, while one’s friends are dead and one is alive. (“[W]hy had they not / killed me — why did they fire that warning?”)

6

And then later, guilt about surviving. Guilt about suppressing one’s political instinct for those two years of the party line. Coming to help Europe, to stop the slaughter of the Jews, too late. Where were we when they needed us? Guilt, too, about (now that the war is over) the awarded Purple Heart having been awarded, about leaving the exiled Left for the return to country and poetry, to the beautiful quiet peaceful “shack on the coast” of Maine (looking back out across the Atlantic), doing nothing much but smelling the scent of the pine needles. A scent that, anyway, reminds him always and ever of the haunted French forest.

7

The knife at the end of the poem is perfectly opaque: the knife of the lamb — merely to butter one’s daily abundant American bread? Or the sharp killing knife-likeness of the war, the war-like imagination. George Oppen at 100 bespeaks the reason to — and also the reason not to — affirm the reality of the political act outside the poem. The best thing about the problem is that, here, it is inside it, as follows:

8

I believe

in the world

because it is

Or:

I believe

in the world

because it is

impossible.