| Jacket 36 — Late 2008 | Jacket 36 Contents page | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/36/r-coultas-rb-morse.shtml

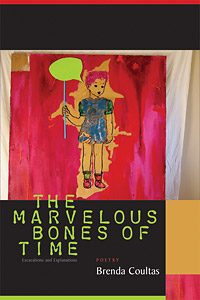

Brenda Coultas

The Marvelous Bones of Time: Excavations and Explanations

reviewed by Jesse Morse

140pp. Coffee House Press. paperback. US$15:00 9781566892049

This review is about 5 printed pages long. It is copyright © Jesse Morse and Jacket magazine 2008.See our [»»] Copyright notice.

1

In her second full-length release from Coffee House Press, Brenda Coultas continues the investigative, documentary process she began in her widely influential and successful A Handmade Museum (Coffee House Press, 2003). Though the actual subjects of documentation are less found-object (the primary substance of documentation in the greater part of A Handmade Museum being trash from New York’s Bowery) than first or second-hand stories, her process, if such fractured, prosaic work can contain a recognizable process, is quite similar.

2

‘The Abolition Journal (or, Tracing the Earthworks of My County)’ makes up Book I of The Marvelous Bones of Time. In Coultas’ own words:

paragraph 3

‘The Abolition Journal’ is an investigation into borders, namely the north-south border between Daviess County, Kentucky and Spencer County, Indiana, where Abe Lincoln spent his childhood (and me too, different centuries!). This is an investigation into the largely undocumented history of the area, especially of the Underground Railroad, slavery, and racism. The laws of these two counties separated by the Ohio River–one a slave culture and the other free–were equally, if differently, discriminatory. (Author Statement, Coffee House Press)

4

Coultas incorporates folktale, personal memoir, historical anecdote, lists of names and places, lists of lost names and places, pejorative jokes - any small revelatory incident or fact manages its way into Coultas’ work. And, as we found in A Handmade Museum, Coultas employs her unique, seamless weave of poetic sentences. In her aptly chosen chronologies, including only that which, in Ginsberg’s words (as Coultas freely admits), is ‘vivid,’ the sentences become poems.

5

Looking from the free state

there is a river then a slave state

Turn around and there is a slave state,

a river

then a free state

I was born between the free side and the slave side, my head crowning on the bridge. I fully emerged in an elevator traveling upward in a slave state. I have shopped in the slave state and eaten barbecue there. I have walked along the riverbank in the slave state and looked out at a free state.

Lincoln looked out over the river and saw a slave state and he was born in one (Kentucky), like me, but was raised in a free state (Indiana), like me. We were white and so could cross the river.

Question: are there any abolitionists hanging from my family tree? (p.17)

6

Coultas sees and writes the historically ‘free’ and ‘slave’ states as existing in the present. She crosses temporal and geographical borders. By placing herself alongside Lincoln, by moving herself back in time and bringing Lincoln to the present, Coultas implies the gravity of today’s racial inequalities. ‘We were white and so could cross the river.’ How different are things, really, since Lincoln’s time? What privileges are still afforded only to whites? The mundane act of crossing the Ohio River (no doubt over a bridge in a car) becomes revelatory in this light. It requires ways and means we rarely think of, ways and means Coultas works subtly (with simple tense and pronoun changes) and overtly to unearth.

¶

Brenda Coultas.

Photo Bob Gwaltney.

7

It’s impossible to read this book and not think of Ed Sanders. His blurb adorns the back. He has dedicated himself indefatigably to investigating history through verse, to retelling that history. Coultas was a student and assistant of his at Naropa University. And while following in the tradition of Ed Sanders’ investigative poetics, Coultas, like any good student, reaches further. While Sanders, importantly, focuses on alternate histories, centralizing characters from the fringe, much like Howard Zinn, Coultas in fact admits the fallible nature of history itself, even implying that her own history is untrustworthy (the above quote a perfect example). That implication, her awareness of it, leads to extremely thoughtful and exciting poetry.

8

Of Lyles Station in 1849

I could certainly write ‘the best cantaloupes in these sandy bot-

toms,’ and

‘the first African Methodist Episcopal church.’

I could write ‘a station existed run by a freeman Thomas Cole.’

I could write ‘these nearby whites

David Stormont

John Caithers

David Hull

assisted passengers.’

I could write, ‘the author of Lyles Station Yesterday and Today asks why this history has been left out of the textbooks.’ (p.28)

¶

9

In an unusual juxtaposition, Book II of Marvelous Bones, ‘A Lonely Cemetery,’ is composed entirely of brief anecdotes about paranormal activity. They stem from various locations and various people, some close to Coultas, others not. In an interview with Marcella Durand from 2004, Coultas reveals:

10

The only kind of criteria I have is that the person believes it to be true. They may be found wrong later, but this is something they believe to be true. It’s an eyewitness account, or even a secondhand account of an experience. (The Poetry Project Newsletter / October, November 2004).

11

Obviously, this range of inclusion lends itself to a certain outlandishness. Yet Coultas relates the hauntings so matter-of-factly that it is impossible not to envision them. Strangely, and largely, perhaps, due to the content, I often felt like I was watching television, some sort of ghost tracking program, while reading ‘A Lonely Cemetery.’ As unfortunate as that sounds, the tales were largely entertaining, and worth re-reading. Nevertheless, in the end, the work felt less essential, less invigorating than the work in ‘The Abolition Journal,’ (unless, perhaps, you are haunted by ghosts).

12

Another Haunting / Same Cemetery

A woman at a yard sale told Robert this story about spending the night there. She was out for a walk when she heard a woman and man arguing. She could not locate the voices, but the argument was growing heated. She looked for them among the crypts. One voice said ‘It’s all your fault.’ She heard them call each other Gladys and Fred. She resumed walking and she saw a family gathered around a headstone, and the names Gladys and Fred were inscribed on it.

At closing time, the guard cleared everyone out and a dog ran in. Worried that it was lost, she went after it, got locked in, and spent the night inside the cab of a tractor on the grounds. She kept hearing a crackling noise, and every time she tried to leave the cab, she felt sick. The dog would bark but when she let him out, he wanted right back in. Afterwards, for a year, she only related to animals, and she was afraid to go out at night. (p.99)

13

The lingering question from Marvelous Bones, then, is what drove Coultas to juxtapose these two distinct books [distinct not just in content, but in style–the fractured, investigative line of ‘The Abolition Journal’ done away with for narrative blocks of prose (perhaps in response to a desire to somehow normalize and authenticate these paranormal findings to the reader)] under one title?

14

Well, there is a kind of lingering haunting that runs throughout Coultas’ investigations in ‘The Abolition Journal,’ the work of uncovering a forgotten history. Though the ghosts and spirits of ‘A Lonely Cemetery’ have specific places, dates and times, perhaps, metaphorically, by placing ‘A Lonely Cemetery’ directly after ‘The Abolition Journal,’ Coultas uncovers the presence of ghosts from her own, historically troubled Spencer County, ghosts that haunt the author herself. These histories, fact or fiction, uncovered or hidden, normal or paranormal, exist. Coultas is driven to tell them. Poetry is her chosen medium.

15

More than an investigative poetics, then, Coultas has created a poetry of archaeology. The investigative technique uncovers a vast landscape of soil, artifacts and spirits. The authenticity of the tales, of the histories, seems irrelevant in this light. The important point is that Coultas is working, that she is digging, and, in continuing to dig, carrying her poetry into unique and fresh territory.

Jesse Morse. Photo Tim McCaffrey

Jesse Morse lives and writes out of Portland, Oregon. His work, reviews and interviews have recently appeared in Mirage #4/Period(ical), 31 and Jacket. Work forthcoming in Vanitas. He co-curates the journal and reading series Smorg (http://www.smorgreadingseries.blogspot.com). And rotates the lo-fi publication Pop Seance with the poets Erik Anderson, Richard Froude and Ryan Newton.