read Time magazine's article on Jacket

read Time magazine's article on Jacket Glen Helfland, in San Francisco Gate magazine

Glen Helfland, in San Francisco Gate magazine Peter Forbes on Jacket, from the U.K. Guardian

Peter Forbes on Jacket, from the U.K. Guardian Ron Silliman, on his web log, from Philadelphia

Ron Silliman, on his web log, from Philadelphia

“…not only the most well-edited poetry journal online, but the most widely perused as well.”

“Australian scene” — Time magazine (Pacific) — April 23, 2001

POETRY and power tools aren’t often found side by side. But the cordless drill in John Tranter’s book-lined study is there in the service of literature. Tranter, 57, a Sydney poet, is teaching himself bookbinding: the drill is for piercing stacked pages before they’re sewn together. Near it, snugly bound in green buckram, lies a sample of his handiwork: a copy of Tranter’s poetry journal Jacket . This single issue is so big — it’s 2.5 cm thick and weighs 1.25 kg — that it would be impossibly expensive to print in any numbers, let alone ship to literary hubs like London and New York. Which is why this tome, and another one Tranter gave to American poet John Ashbery, are the only copies of Jacket in existence.

Make that between covers. For Jacket also comes in an electronic version, assembled on Tranter’s computer in this bright back room of his Balmain home and published around the globe on the World Wide Web (http://www.jacket .zip.com.au/). There, free from weight worries, it flourishes. Influential literary journals like The Paris Review do well to sell 12,000 copies. Jacket , in 13 issues, has logged over 280,000 hits — though many, he concedes, are accidental, people wanting “something smart in dinner jackets, perhaps.” It has also won several awards — last year Britannica.com named it one of the best sites on the Web.

In the welter of literary e-zines, Jacket stands out for its stylishness (it was named, Tranter says, with smart attire in mind). Its pages are easy to download and read onscreen, and there’s no annoying animation. By publishing only material he has asked for, Tranter also spares readers the self-indulgence that mars so much writing on the Internet. With poetry, reviews, interviews, color images, an audio welcome message and sly editorial humor, Jacket is (to quote Tranter’s poem “The Popular Mysteries”) “a gift factory/ as silly as a lucky dip.” And as rich. Printed out, its 950 text and image files would cover 2,000 pages — all, says the editor, “free as the breeze.”

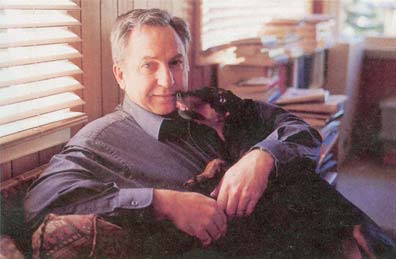

Photo of John Tranter by Ross Bird for Time

Tranter, who started writing and publishing poetry in the ’60s, revels in the anarchic freedom of the Net. With an unpaid staff of “five” — all, he jokes, named John Tranter — he can publish what and when he likes, uploading items as he edits them. (His taste leans to the opaquely avant-garde.) He doesn’t charge an entry fee for Jacket — if he did, he says, “my readers would simply go elsewhere.” And while that means there’s no money for contributors, “I’ve never had anyone say they wouldn’t send me something because there was no payment.”

Poets these days don’t expect to get rich — the world is too busy watching television. But the Net lets Tranter piece together a sizeable readership (mostly American), and gather writers from the U.S., Britain, Australia and France, as easily as if they all lived on the same block. “I’d guess that about half the readers have no real idea Jacket comes from Australia,” he says. “And I don’t feel it does. It comes from the Internet; it’s almost an outer-space thing.”

Unworldly poets might take the same view of Tranter’s technical savvy, which he says some of his peers find “weird.” (He bound a copy of Jacket ’s second issue for Ashbery, a computer-shy friend whose work it featured, because “I had the sneaking feeling he’d never actually seen the magazine onscreen.”)

But Tranter has always had an affinity with machinery. Growing up an only child on a farm in southern New South Wales, he enjoyed “fixing things with a bit of fencing wire.” And when he started publishing poetry magazines — using facilities at the print shop where he worked — he found as much romance in Linotype and Gestetner machines as in the work of Rimbaud and Ginsberg.

Tranter’s solitary childhood left him “rather shy,” he says. Jacket lets him socialize on his terms. “It’s like a party, with all these voices discussing things.” The Net makes networking easy: e-mailed friends become contributors; contributors located through online poetry groups become friends. Tranter frequently travels abroad with his wife Lyn, a literary agent; when he gave a reading in New York recently, he says, “Almost everyone who came I had met through Jacket , or they introduced themselves because they knew the magazine.”

Jacket ’s hypertext structure fosters its own connections: with no page numbers and no defined start or endpoint, visitors follow their fancy from link to link, issue to issue. From a familiar name on the contents list, they might click to a poem, then a related article or interview, then a new poem on the same theme. “It’s like a computer game,” Tranter says. “You can go through it, then start again and go through another way.” Each reader takes a different route — and makes a different mini-magazine. Between covers. Jacket is the same for everyone. On the Web, it’s do-it-yourself poetry.

IN THE FICKLE world of the Web, it’s nice to know there are sites that are resistant to shifts in fashion and economy. Literary Web sites, for example, traffic in a form that moves at a less frenetic pace than other online media does. Communities of writers, especially those poets, spoken-word artists and experimental-prose writers whose works rarely make it to the shelves at Barnes and Noble, or even into the farther reaches of Amazon.com’s warehouses, have made effective and enduring use of literary webzines — and they may barely have noticed the fallout of the technology crash.

For a publishing cottage industry of small, independent presses and copy-machine poetry rags that, in pre-Internet days, were by necessity limited to three-figure circulation, the advent of the Web has made the prospect of distributing new, difficult, highbrow or edgy pieces of writing cheap and globally accessible. As one poet jests, ‘When those poems go live, everybody and their mother will be reading them.’

To scratch the surface of this international online subculture is to reveal a surprising number of publications that are well edited, inventive and sometimes even spiffily designed literary showcases. I polled poet and writer friends and was quickly directed to a thriving arena of journals, resource portals and hybrids of art, writing, news and other types of information.

Almost everyone I contacted pointed me to Jacket, an Australian site that’s perhaps as close to a traditional print poetry journal as can be created online. The site, which publishes a new issue roughly every two months, includes themed sections — the latest issue features an all-star tribute to luminary Kenneth Koch — reviews, poems and substantial scholarly papers; see Marjorie Perloff’s article on ‘Translatability in Wittgenstein, Duchamp and Jacques Roubaud’ in issue 14.

Published by an office of one — Sydney-based poet John Tranter, who claims to run this hefty enterprise for $1,000 a year — the journal is very well organized (contents have been plotted out through December 2002) and are posted piece by piece. This is labor-of-love territory, with publisher/editors operating their sites on miniscule budgets or occasionally with the support of foundations or academia, but Tranter boasts in an e-mail that since the publication’s debut in October 1997, the site has attracted over a third of a million visits, making Jacket one of the most widely read poetry magazines of all time.

Numbers, however, are relative in the poetry world. ‘Sappho, Callimachus, Catullus, Li Bai and John Donne all had small audiences for their poetry,’ Tranter writes in a why-I-do-it essay called ‘The Left Hand of Capitalism.’ ‘And any serious poetry faces the same situation today — it’s not a profitable market anywhere in the world.’

There are hungry international consumers, though, and this method of distribution seems to reach them more effectively than the bookstore circuit does. Tranter writes, ‘In the first issue of Jacket, I published an interview I had recorded with the British poet Roy Fisher, and received an enthusiastic e-mail from a fan. The fellow was grateful for the chance to read an interview with his favorite poet, he said, and went on to explain, ‘It’s hard to find material on Roy Fisher up here in Nome, Alaska.’’

The location of the publishing house, as is usually the case with Web endeavors, can be irrelevant. Frigate, a review of books and other literary pursuits that appears, based on its masthead, to have a large staff, boasts a sense of internationalism, with a current issue devoted to ‘The Anglophone Transpacific.’ In fact, the publication is a concerted effort by editors and contributors from geographically diverse desks. Patricia Eakins, in an e-mail from New York, explains that she has editors in Philadelphia, San Francisco, Massachusetts and France. The cobbling together of an issue, she adds, takes place entirely through online communication.

‘Creating the site has been a exhilarating, exhausting and eye opening,’ Eakins admits. ‘It is amazing what one person sitting at a computer can do! People often think that Frigate must have a ‘real’ office with cubicles and watercoolers and the like. Instead, it is all in the air.’

‘I see these zines as an outgrowth of the mimeo revolution of the 60s,’ says Bill Berkson, a poet and critic and a professor of liberal arts at the San Francisco Art Institute. As a young New York poet during the 1950s Frank O’Hara period, Berkson has witnessed first-hand the publishing evolution. ‘We used to have collating parties, assembling the things,’ he adds. ‘The webzine thing isn’t as sociable; there’s less face-to-face time. But that’s the way it is in the electronic age — quick and inexpensive communication is key.’

San Francisco-based writers Dodie Bellamy and Kevin Killian edit and distribute 200 copies of a mimeo-style publication called Mirage. While they have no plans to digitize their very limited-edition publication — Bellamy playfully calls this idea a ‘rumor’ — they appreciate the electronic form.

‘I think there’s a lot of high-quality stuff out there,’ Bellamy says. Her own experimental prose has appeared on numerous Web sites, including Mark(s) and Stretcher (an arts and culture site I had a hand in founding). ‘It’s a good venue for experimental-writing communities, because there’s no cash economy for that kind of stuff anyway,’ Bellamy adds. ‘The publications come out more often and have more universal distribution — you announce on a listserv, and you get people all over the world reading your stuff.’

Another site with decent numbers, though one with a radically different editorial viewpoint, is the online version of the Dave Eggers brainchild McSweeney’s — a compendium of articles, fiction, essays and literary news snippets of interest to youthful literati — which logs 20,000 unique hits a day. Granted, the site, which has offbeat offerings like the smarty-pants ‘Readers’ Interesting Experiences While Buying, Reading or Traveling with the Print Version,’ has an audience that’s bolstered by the notoriety of a well-regarded and high-concept print publication, but the Web site has different content, and it’s available for free. What does it do that its print counterpart can’t?

‘Well, for one thing, the site can publish more pieces than in the print version,’ explains online editor Paul Maliszewski. ‘We publish more than five pieces a week, things like the letters from Elizabeth Miller’s dad, who fights fires by helicopter, or Jeff Johnson’s football picks, which Yahoo! named as one of the best things on the Internet in 2001. We published some really strong nonfiction relating to the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. Even with our fairly short production schedule, it would have taken a couple of months for those pieces to appear in a print issue.’

Jacket and McSweeney’s are visually and philosophically all about the text, and they’re purposefully clean and simple in design in order to aid Web-page load times. In this way, they resemble the print versions of poetry and lit publications that are simply designed due to the prohibitive costs of high-quality color printing. The Web, however, offers the opportunity to affordably illustrate with full-color art, a prospect that can foster an exciting dialog or interplay between writers and artists. Or at least add a little spice to the page.

Low Blue Flame is a Memphis-based site that ingeniously creates an interplay between image, text and playful conceits. Visually appealing and easy to load, the third issue is visually cohesive, with colorful, surrealistic Dick-and-Jane collage motifs and texts generated with inventive tropes — in one case, writers such as Mark Ewart, Eileen Myles, Bruce Benderson were asked to write text to accompany pages from a vintage Wild West-themed coloring book.

A section called Deep Thoughts pairs person-on-the-street snapshots with answers to the question, ‘What were you thinking just now?’ The responses are short, sometimes poetic, sometimes banal. Even the interview format is given a twist here — the aforementioned Kevin Killian is a featured interview subject, and his passion for celebrities is addressed by letting him lob back trenchant quips when he is tossed the names of movie and pop stars: ‘Leo DiCaprio: I thought he was retarded in ‘What’s Eating Gilbert Grape?’’

The site is organized by novelist Brian Pera (whose book ‘Troublemaker’ is just out in paperback), who is interested in addressing the Web’s strengths and weaknesses. ‘I’m not convinced that people really read on the Web,’ he says. ‘People look at things online in a scattershot manner. I’m trying to create a mix of elements that won’t extinguish someone’s attention span. I think of it less as something people read in its entirety than as a teaser to make people want to read more.’

Things get more technologically complex at Arras, a portal-like site that links to a number of splashy Web sites that explore notions of text. There are links, for example, to a theory-heavy but graphically sharp piece called ‘New Digital Emblems’ and something called The Pornolizer, which inserts nasty language into any Web site you care to submit.

A larger number of sites, however, are more humble, community-building affairs. San Francisco-based poet Del Ray Cross started (Shampoo just two years ago as a way to keep up with poet friends in Boston. (He will celebrate its anniversary and 10th issue with a reading on March 1.) Cross has seen submissions to his site, which features poetry and a smattering of art in each issue, grow continuously. It’s an ad-free, open-submission deal in which poets are encouraged, in a large-font link, to submit their work on the homepage. ‘It’s really taken off,’ he says. ‘I get a lot of submissions now, and it’s becoming more difficult to find time to do the site and be a writer.’

The interactive nature of Web sites allows for easy communication and ready access to a vast pool of material. Whereas many print poetry journals charge writers an income-generating fee to consider their poetry, many sites rely on online submissions.

‘Every now and then, I’ll solicit a piece of writing from someone I know, which basically means I hear that they have a story and I ask them to write it down,’ admits McSweeney’s online editor Paul Maliszewski. ‘Usually, there’s a phone call involved, some arm-twisting and not a little begging. But 90 percent or more of what we publish arrives first as unsolicited submissions from readers.’

Shampoo editor Del Ray Cross basically selects whatever submitted work he likes, and he tends to like work that’s somewhat playful, and tends to mix more established poets with unknowns. One would surmise, however, that with an open call for work and the ease of e-mail, he receives quite a bit of junk. ‘I’m getting more bad stuff,’ Cross concurs, ‘but getting a lot more submissions — these days, around 25 poems a week.’ He admits, however, that at least half of the submissions are rejected. ‘I try to appreciate something in whatever I get,’ Cross says. ‘A lot of other magazines are stricter in genre of what they publish. I like to have a mix.’

He adds, ‘I published a poem in this issue by my cat.’

The free-and-easy tone of these online publications, however, may tilt a bit too much toward the free side for some. Because webzines are a new arena for writers and editors, their legitimacy is not yet established. And like other Internet interactions, practitioners often have a sense of ambivalence.

A number of writers say that when a piece appears online, publishers are less likely to consider the work for print publications. Others point out that some literary grant-giving organizations have inconsistent policies when it comes to recognizing a webzine as a valid citation. While these issues pose a dilemma, most writers opt for getting their work out in the world.

Most of the writers and readers I contacted for this story, however, qualified their response by saying that although Web access is an amazing, democratizing thing, the printed page is still their first choice as a reading format. Still, the e-zines have become too valuable and resourceful a component in the literary universe to live without. So, if and when the fickle Web economy hits another bump, these sites will most likely still be comfortably curled up with something good to read.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Glen Helfand is a freelance writer, critic, and curator. His writing on art, culture and technology has appeared in The Bay Guardian, Wired, Limn, Salon, Travel and Leisure and Nest.

glen_h@sfgate.com

Thursday June 6, 2002 The Guardian

POETRY is a classic web subject area: a vast sprawling cottage industry with visibility and distribution problems in the offline world. When I edited Poetry Review I used to get wan little letters saying ‘I can’t find your magazine in your newsagents — how can I buy a copy’. If only they’d known: the terrible economics of newsstand distribution; the measly 40% take on the cover price — and that’s if you sell them; the returns can be huge. So we were subscription plus upmarket bookshops, and sample pages on the web of course.

On the web, distribution is no problem: it’s all available 24/7, and everyone is equal, at least theoretically. There is the perfect book-buying system in Amazon, there are online poetry magazines and newsgroups. The publishers have websites so you can see what’s available (bookshop poetry sections can be very patchy).

Perfect in theory. How does it measure up? Google produces 7.25m pages for ‘poetry’; ‘rock music’ only manages 422,000, ‘food and drink’ 606,000; even ‘Britney Spears’ only turns up 1.2m. So there is a lot of poetry out there.

The Poetry Society site is a good place to start: it’s a huge resource, maintained with great energy by the Society’s Californian web wizard, Jules Mann. As well as all the Poetry Society’s own activities and its online Amazon-style shop — you can join online, enter the National Poetry Competition and buy a wide range of publications — it links to all the useful sites.

If you are interested in a particular poet or a poem or even a line from a poem, you can do worse that simply type it into Google: if it’s there, you’ll find it. It used to be hard for beginners to the poetry scene to find their way: now the web will get you up to pace remarkably quickly. The Poetry Library has a list of magazines and once you have the titles you can check out their web presence on Google. And if you’re really stumped for that lost quotation the Poetry Library’s Lost Poems Noticeboard now has its virtual equivalent — just type your request into the form and someone out there is almost certain to have what you need.

The Poetry Society site lists forthcoming publications from the major publishers and most of them have their own site. Poetry Society links will also find you 20th-century poets with good websites devoted to them, eg Simon Armitage, Seamus Heaney, John Kinsella, Roger McGough, Sylvia Plath . A new resource coming in June is the Contemporary Writers website from Booktrust and the British Council. It will include novelists as well as poets and provide a useful profile of 250 UK writers, growing at the rate of 20 per month.

Bloodaxe Books publishes more of the best contemporary English poetry than anyone else, so its website, recently rejigged and growing, offers a real taste of the best of the scene.

The web is good for listings and you’ll find a lot of gigs at The Poetry Kit. For London events, Poetry London is the place.

The web, of course, is international, and poetry used to be very insular. But there’s no reason now not to check out what’s happening in other countries. The prince of online poetry magazines is Jacket, run from Australia by the poet John Tranter. It has never been a print journal. The design is beautiful, the contents awesomely voluminous, the slant international modernist and experimental. Issues of Jacket grow slowly so that you can read parts of the June issue already: it is devoted to Ern Malley — the great Australian Poetry Hoaxer — and includes the complete poems and a radio documentary in Real Audio.

Good portals save you a lot of time and trouble: Web del Sol is a large US site that pools the resources of dozens of magazines. You can find classic US magazines such as Agni, Kenyon Review, Sulfur, and Prairie Schooner as well as, further out, Exquisite Corpse and Painted Bride Quarterly. Poetry Daily has its ear to the ground for contemporary American poetry.

Finally, the poetry workshop is the engine room of poetry. If you don’t have one near you in real time and space, Yahoo lists 1,530 poetry groups: one of them must be yours.

On Wednesday, I thought to write a note on the changing status of literary magazines in the age of post-mechanical reproduction. For, while there are certainly some print journals — Chain, Kiosk, Poker, Combo — as great as any that have plied their trade in & around the fields of verse, there is also Jacket & a rapidly growing legion of online journals that have demonstrated that they can be just as well-edited — and just as creatively formatted — as anything in print. I was thinking about a conversation I’d had with Laura Moriarty at the books exhibit at the MLA last month — she had told me, in so many words, that my contention that the chapbook was the primary unit of exchange or of production — I can admit to being vague here — in contemporary poetry was so much hooey. She sees, as she noted, so many more books than I do — and of an aesthetic breadth that I can barely imagine (indeed, I could never work at an operation like SPD precisely because its view into the world of poetry, not unlike that of institutions like Poets & Writers or CMP, would depress me to the point of psychic paralysis). Bookstores hate chapbooks for obvious reasons — the cost of retail space argues against presenting anything not a best-seller face up to potential consumers. But, even with perfect binding & high-format covers, “nobody wants journals, either.” On this, Laura & I were forced to agree.

This puts the print magazine into a curious double-bind, one from which I’m not at all certain it will be able to emerge. The expense of publication is prohibitive. Distribution borders on the impossible. Unlike a book, back issues become an albatross of storage. When I was with the Socialist Review in the 1980s, we struggled with finding the right balance on any given print run between enough volume to drive down the cost per copy & literally having to bring in dumpsters to handle overstock that was crowding us out of our four-room office in Berkeley.

Jacket, with its strategy of publicly building each issue up from scratch on-line, actually solves one of the inherent problems of the online journal: how to cope with the out-of-sight/ out-of-mind issue that can make “distribution” online even more of a challenge than getting bookstores to carry little magazines. Where most other online zines have to start from scratch getting a readership for each & every issue, Jacket gives its readers a reason for checking in with great regularity — there’s almost always something new. This I suspect makes it not only the most well-edited poetry journal online, but the most widely perused as well.

Journals exist for a reason — yet in the print world, the most common path for a small press publisher has been to begin with a journal & to shift at some point into doing books. A lot of presses go through a both/ and stage, but sooner or later, it’s usually the journal that gets jettisoned. Publications with the lasting power of Jacket do exist of course — think of Sulfur, let alone the institutionally based journals like Chicago Review — but by keeping all 5,000 web pages (some of them quite long) online, Jacket demonstrates how the online journal can even trump the availability of something like Sulfur or Poetry. Too often e-zines keep only the current issue online — Jacket really is the example of how to keep material “in print” electronically. Against this, I look at the one narrow bookcase I do devote to journals (plus a stack of still-to-read ones atop another bookcase). The reality is that there just isn’t enough real estate in my bookshelves to accommodate everything. I have ready access to anything in Jacket in a way that will never be possible with, say, boundary2.

All of which I was about to write on Wednesday, when Verizon’s DSL service to the Philadelphia region (“and the state of Delaware” says the tech support hotline) went down for over ten hours. Which reminded me of the weak link in this process altogether. Sigh.

Friday, January 14, 2005

At: http://ronsilliman.blogspot.com/2005_01_01_ronsilliman_archive.html

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/00/jacket-reviewed.shtml