| Jacket 37 — Early 2009 | Jacket 37 Contents page | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 35 printed pages long.

It is copyright © Kent Johnson and Don Share and David Shapiro and Jacket magazine 2009. See our [»»] Copyright notice.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/37/iv-shapiro-ivb-kent.shtml

JACKET

INTERVIEW

David Shapiro

in conversation with

Kent Johnson

Introduction by Don Share

Date: 2009, by email

More on David Shapiro in Jacket 23:

[»»] DS in conversation with John Tranter, 1984

[»»] Thomas Fink: David Shapiro’s

‘Possibilist’ Poetry

[»»]

David Shapiro: Six poems

(from A Burning Interior, 2000)

[»»]

Carl Whithaus — Immediate Memories: on the Poetry of David Shapiro

[»»] Nathan Hauke: Meditations on David Shapiro: Memory and ‘Lateness’

[»»]

Kent Johnson: Poem Upon a Typo Found in an Interview of Kenneth Koch, Conducted by David Shapiro

And in Jacket 15: David Shapiro’s 1969 interview with the late Kenneth Koch.

1

David Orr recently fretted over what constitutes “greatness” in poetry in a recent controversial piece for The New York Times that caused much additional fretting [1]. Orr wrote that American poetry “may be about to run out of greatness, for the most part because greatness has turned out to be an increasingly blurry business”:

Paragraph 2

Greatness is ― and indeed, has always been ― a tangle of occasionally incompatible concepts, most of which depend upon placing the burden of “greatness” on different parts of the artistic process. Does being “great” simply mean writing poems that are “great”? If so, how many? Or does “greatness” mean having a sufficiently “great” project? If you have such a project, can you be “great” while writing poems that are only “good” (and maybe even a little “boring”)? Is being a “great” poet the same as being a “major” poet? Are “great” poets necessarily “serious” poets? These are all good questions to which nobody has had very convincing answers.

3

I’d hate to think of poets really wrestling with all these strawmen. Near the end of the piece Orr knocks them all down, anyway: “the idea that poets should aspire to produce work ‘exquisite in its kind,’ as Samuel Johnson once put it, is one of the art form’s most powerful legacies.”

4

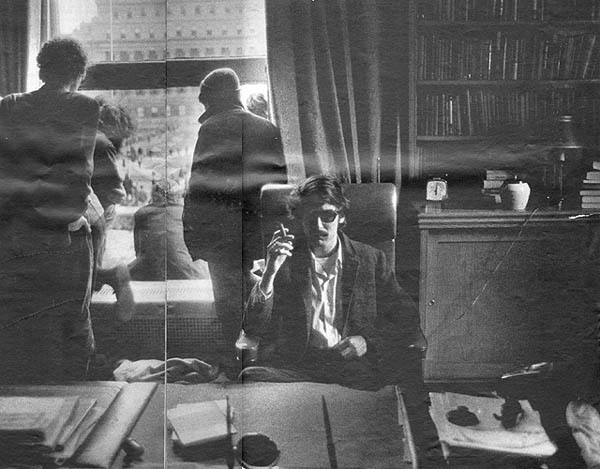

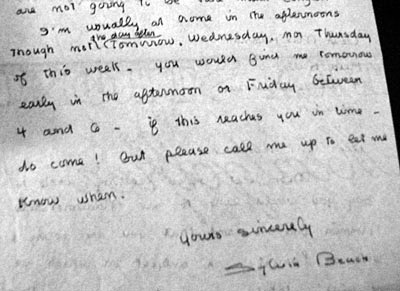

In light of all this, it seems both quaint and extraordinary that, sensing him to be exquisite and one of a kind, an editor once gave David Shapiro this terrible advice: “Don’t meet great men anymore. It is time for you to be a great man.” As it happens, that time was already long in the making: at the age of thirteen, he realized that he was brought up (he tells Kent Johnson in the following interview) “so bent out like a twig in a pool that I wanted to read everything in the open stacks of the world.” He wanted, like Pound, to “know more about poetry than any other person in the world” ― a path to greatness if there ever was one. It began for Shapiro in the mysteriously named Deal, New Jersey, where he grew up, and led to New York City, where he attended Columbia University and became notorious not for his reading, though great books are read in the curriculum there ― but for sitting at the university President’s desk and smoking a cigar. The desk and cigar belonged to Grayson Kirk, President of Columbia during those heady days of campus unrest in 1968. (Shapiro has said that the cigar tasted “terrible.”) An iconic photo, reproduced in Life magazine, became both a source of pride and irritation for Shapiro, already a prodigy in poetry, but famous for something else. With hindsight it’s possible to speculate that he never quite wanted to be in the limelight again. And so Shapiro subsequently spent much of his life getting to know the great, from Lionel Trilling to Jasper Johns.

David Shapiro, in the President’s office at Columbia University. The photograph was taken by Blake Kirkwood, who describes the scene thus in a memoir article for the Huffington Post: “Once ensconced in the comfortable couches of the president’s office at Low, we helped ourselves to his private stash of Madeira and exquisite cigars. I photographed a longhaired David Shapiro (a well known poet who has since taught at Columbia) sitting at Kirk’s desk smoking one of these cigars and sipping Madeira. (The picture was widely circulated in newspapers and magazines around the world.) Despite our fun, we were careful about Grayson Kirk’s possessions and his fine antiques and art. We were, after all, children of the elite.” Kirkwood’s piece is titled “40 Years Ago Today, The Police Tried to Kill Me At Columbia University” [Huffington Post]

5

The most striking thing about meeting Shapiro in the flesh is that his conversation is a tapestry of quotations from the great, preceded and followed by anecdotes that serve as a kind of Talmudic, intertextual commentary. “Out of disunity, out of being torn apart, comes thinking.” So Shapiro recalls Hannah Arendt saying ― attributing the quote herself to Hegel, though he tells Johnson that he has never been able to find it anywhere. These profound and resounding snippets are quirky and endlessly edifying ― and virtually anything can trigger them. This is because Shapiro has been, as he admits, “the Narcissus who is always also already Zelig among the icons… If I refer to names, it is because of what I hope is the humility of Jews. We quote, but not in the past tense.”

6

It’s easy to see that Shapiro is a man for whom, as Ange Mlinko puts it in a recent review for Poetry magazine, “language is always larger than the poet.” And quote copiously though he does, he is himself greatly quotable: “The poets rage, because they cannot see anything but the shadows. The philosophers rage, because they see nothing but precise lighting conditions.” “It will be up to subtle critics to see and calculate what was done and by whom and what is vital beyond any trivial idea of form.” “A lot of shamelessness goes into doing any work.” “I am intrigued by the possibility that literary critics should at least be able to imitate something.” “Poets are never poor; we practice an arte plena, or full art.” “Learning a hundred recipes for poetry is still as unproductive sometimes as learning the antithetical proverbs that say talk to a fool or don’t talk to a fool.” And there are too many more to spoil by quoting them in an introduction.

7

Is Shapiro a great poet? His first books are amazing, not just as the works of a teenage prodigy, but because they seem so contemporary today – maybe even now still ahead of the curve. I remember that when I encountered Poems from Deal for the first time, it didn’t occur to me that there could be such a place in reality: Deal sounded as exotic as the places that turn up in Stevens’ poems: half Eastern suburbia, half hooka-cloud. It’s as if I were reading these poems through the half-open eyelids of a hypnagogic state far from Connecticut or New Jersey. But over the years Shapiro’s work has traded the abstractions of the dreamlike for those of emotional intensity, as in the exquisite riffing on Percy Sledge’s “When a Man Loves a Woman” in “Song,” from To An Idea, or in the mournful reconstitution of Walter Benjamin and other victims of historical circumstance in After a Lost Original. The latter book quotes Gershom Scholem: “There was nothing like being alone with Walter Benjamin. It made one want to read. The source of that remark is also lost.” A great rescuer by temperament, nothing is ever lost on Shapiro. Even his most recent poems still revivify those whom he wryly calls “the living dead” ― they’re not zombies, but the highly-esteemed likes of Meyer Shapiro (the art critic and scholar who was his mentor), Frank O’Hara, Fairfield Porter, Kenneth Koch. His poems, like his quotations and anecdotes, wrestle the past back into the present. In a new poem called “A Riverdale Address” ― he lives in Riverdale now, not Deal ― he shifts wildly and improbably into the new century by anachronistically name-checking Pat Benetar’s “Love is a Battlefield;” haunted by hopefulness, the poem ends:

8

And that without bigness

we take from their greatness

a complete devotion

to one note that in them

we live and vainly die

And that the poetry

of earth is as good

as the poetry of language

And that poetry of

the self by the self and for

the self will perish

from the earth and

that the poetry of the

earth without contempt

for an apple (The whole tree

repeats the leaf)

will not perish, like the earth.

9

Leave it to Shapiro to have arrived at a true post-avant, post-language-poetry, Obama-era poetry, all avant la lettre! But I didn’t answer the question about his greatness, and perhaps he himself addresses this best, that is to say, obliquely: “The terror of the poet: that he has already written his best work.”

10

When his New and Selected Poems (1965–2006) appeared, he told Richard Klin, “I sometimes think I’m in that wonderful category of ‘neglectorinos.’ Recently, I think I’m getting lucky again because I am so old. It’s a kind of sympathy vote.” Do people still marvel that he published his first poem in Poetry at the age of sixteen? That his first book, January, appeared when he was eighteen? Maybe youthfulness matters less now, in thanks part to the revolutions of the sixties in which Shapiro’s blossoming as a poet was situated. Long associated with slightly older poets like Ashbery, O’Hara, and Koch, he is a bemused survivor, joining their ranks while slyly demurring; “We are now,” Shapiro says of his poetry cohort, “the grandfathers and less hated by the young.”

11

Of course, nobody hates Shapiro: one loves him because of the things he loves: music, poetry, meeting people, talking energetically about all these things. In her piece on him Mlinko remarked, “There are many kinds of poetry; poetry performs many functions; poetry is more plastic than sculpture, has more microtones than any formal musical system ― with fewer rules. Poetry embraces the whole world. What can match the polyamory of language?” A question with no answer, except, perhaps, what can be discovered in David Shapiro’s polyamorous poetry. Greatness: is there a synonym for greatness? As Shapiro asks at the end of this interview, “is there a synonym for synonym? I tried. I heard the question before I loved the form of a question.”

DonShare

Don Share is Senior Editor of Poetry magazine in Chicago. His books include Squandermania (Salt Publishing), The Traumatophile (Scantily Clad Press), and a critical edition of Basil Bunting’s poems (Faber and Faber).

12

Kent Johnson: Mr Shapiro, the most wonderful thing has happened to me today, January 5, 2009, and I have to tell you about it. No one will believe me.

Just a few hours ago I was on the third floor of an antique mall here, poking around in old books, a pretty large collection of things left by a deceased dealer, and so everything is going for “3 for $5.” Some great stuff, including really old tomes with prints, fold-out maps, stuff like that, a first edition of Understanding Poetry in fine condition, etc. I was looking around to find materials for my son Brooks, who is a poet and collagist.

13

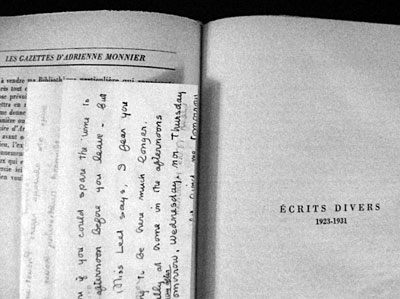

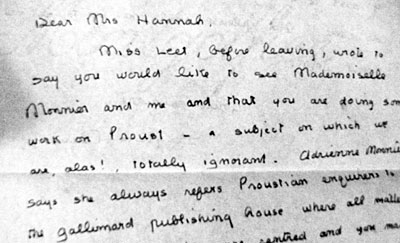

Anyway, as I am leaving, happy with my take, my eyes fall on a book lying face-up on a shelf, the white paper cover detached. It is Les Gazettes D’Adrienne Monnier, 1925‒1945, published by Rene Julliard, Paris. I open the book, and there is a folded letter inside. The sheet, very delicate paper, is approx. 4 X 6 in. is my guess. Both sides are filled with handwriting, a clearly legible script, paper in perfect condition. It is a letter to a Mrs. Hannah, at Reid Hall, 4 rue de Chevreuse, Paris, VI. In it, the writer responds to the addressee’s apparent query about Proust, and mentions that she, along with Mademoiselle Monnier is “… alas!, almost totally ignorant of Proust,” but that she will put her in touch with Maurice Bardou [?], at Gallimard, who will certainly be able to assist with her research. The letter goes on in a very lovely way about when a visit from Mrs. Hannah to the writer’s apartment might be made, and so on. The letter is signed “Yours Sincerely, Sylvia Beach.” Her name and address are printed in blue official stationary type at the top: SYLVIA BEACH, 12, Rue De L’Odeon, Paris, VI. The letter is dated “January 4, 1954.”

14

I found this in Freeport, Illinois, a town that is about as far away from the Paris of the Lost Generation as one may imagine, trust me. I’m hoping that “Mrs. Hannah” is Beach’s quirky way of referring to Hannah Arendt, of course.

15

David Shapiro: Reid Hall, a place where I’ve slept, was always a special place for Columbia kids to stay. Luc Sante, my student, was there, for example, very early in the 70s.He was one of the first of my students to be enthusiastic about post-structuralism when most hadn’t yet understood Lévi-Strauss. It’s a little aristocratic garden with no bullets from the Commune.

16

KJ: Wait, Luc Sante, the translator of the great Felix Fénéon? He was your student? I thought he was an old man! But forgive me, go on…

17

DS: I met Hannah Arendt around 1968 and found her most responsive to questions about Jarrell, poetry, Brecht, and Benjamin. She laughed at me when I tried clumsily to speak of her The Human Condition. The laughter is part of the poem of mine for her. By the way, I have NEVER found something I recall her attributing to Hegel: Out of disunity, out of being torn apart, comes thinking. I turn it into a rhymed silly doggerel. 1954 seems late though, since her own dear friend Benjamin had spent so much time translating Proust… Interesting. Around here there was a bookstore, and I found a volume on purism signed by Ozenfant and gave it back to the owner. I always hate to think I have tricked someone through knowledge. Ha! I did run Shakespeare and Company for a month in 1967 ― Mr Whitman just gave me the keys and left for a month, because he was putting together a magazine… He came back.

18

But how is it that almost everything in literary existence has some kind of tie to you?!

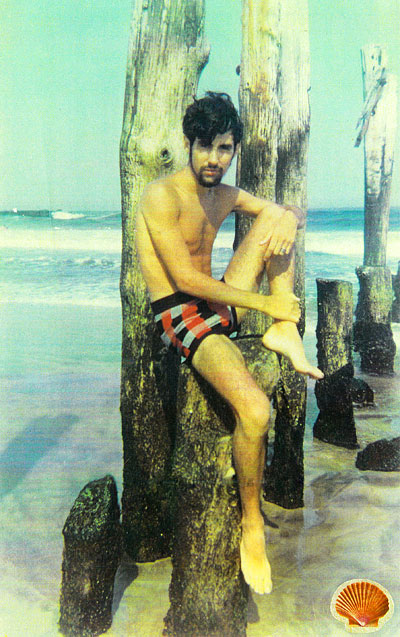

David Shapiro

Photo courtesy University of Chicago

19

No, I know nobody, I am nobody, I know nothing, and feel closest to the “Que sais-je?” motto . In Jewish law, if one doesn’t know, you are required to say: I do not know. But agoraphobes pride themselves on going out into space. I love that sentence about things being related to me, because my psychiatrist and I would both see this as a defect. I have been therefore the Narcissus who is always also already Zelig among the icons. I know how it happened. Phillip Lopate once said it was true that for an agoraphobe-claustrophobe, who hardly travelled, I knew more people in other countries than he had ever found. Allen G. was intrigued by my knowledge of say Sir Yehudi Menuhin. Others think it is merely namedropping and vain. I would agree. The Israeli poet David Avidan once visited me and interviewed me. He noticed not only that I quoted too much, but that I always agreed with the quotations. Whereas he prided himself, he said, on quoting and not agreeing.

20

However, my editor Arthur A. Cohen once said: Don’t meet great men anymore, David. It is time for you to be a great man.

21

However, just as I became ravished by dreams of seeing every beautiful mosaic or Moissac or Souillac, I have never released myself from the Babel-cliché of you must know everything to the famous Tory sociality or liberality of Sir Isaiah Berlin. My mother, I think, was always stunned by her father’s sweetness, and he was always on global trips. So, as I grew up, the idea of the communitarian Trotskyite was central. There was no one in a huge neighborhood that my mother didn’t know and care for. She was a novel-a-day person, but also she was ― having known Sachs, the Freudian, in South Africa and the Reichians of Newark and the communists of New Jersey ― a therapist to many. When she lay dying, so many people visited that the question was heard: What famous person do we have that this is happening? People loved my mother, though I and you must hate a bit the word “people.” She believed in Tolstoy’s forms of teaching and Sylvia Ashton-Warner. Because of her, indirectly, Teachers and Writers came out with an edition of Tolstoy on teaching. What I learned was that to have one’s students tell stories was wiser and nicer than having them fill out formulae.

22

And you? Lequel de vous?

David Shapiro

23

This is what happened. I was brought up also so bent out like a twig in a pool that I wanted to read everything in the open stacks of the world and slowly dreamt of two possibilities when I was 13 ― that I would, like Pound, know more about poetry than any other person in the world (foolish boy), and that I could also “do” music, art, theory, politics, and philosophy as adjunctive to each other and bearing a precise ratio for each other. Knowing that a few masters had done this, I approached mainly the following as an addict: Johns, Cage, Cunningham, Carter, de Kooning, Feldman, Hejduk, Eisenman in architecture, Schapiro, Ashbery, O’Hara, Porter. In music I slowly gave up an interest in the final acrobatics. But I did time to time use New York to see the vanishing geniuses of the Partisan crowd. In France I caught up with Derrida, Kristeva, Sollers, and the end of the Tel Quel coterie and Oulipo folk like Harry M.

24

It’s a shame about Tel Quel, so sad… And I remember that Harry Mathews [2] was, like the poet Linh Dinh, once in the CIA. [3] And geography… What about distant places?

25

Since the Arctic and Antarctic only interest me sadly for deep ecology, I only needed to scour the world from Palestine (as Meyer did) thru Spain, France, Italy, etc. I still don’t know many from Finland or Scandinavia and should have taken an Aalto tour a long time ago, same for Iceland, where Serra now has good sculptures like menhirs. I spent two years in London at a good time, 1968‒70, and finally did get to smell that country. Ashbery wonders why he was suddenly known there. I had spent two years convincing people, haha, like Prynne, haha, that there was something other than Olson and Duncan and Donne. I did love rule systems, but I didn’t want to be the person who spends so much time making the bed he/ she never gets to make love in. Actually the Oulipians make sure to remind one that the rules they invent are not meant for their literary works themselves. This was an error, I believe, in certain Language works. There was an idol-worshipping of rules. I, for example, have always had rules within my works, but I never thought the rules themselves would save me. Examples of my rules: mistranslating Roussel’s prose into rhymed poems, writing from the dictionary, mistranslating Baroque French poetry. “Elegy to Sports” for example, written in 1967, is based on an elegy to Desportes, a poet I have now forgotten. I used to wake up and mistranslate at least one poem of Reverdy a day. I also liked to write rhymed translations of scientific works. “A Man Holding” was mostly written in science museums in Paris. I kept being inspired by their bad or dull labels. Paris! And the Galileo Museum in Florence. The Oppenheim-ruled science museum in California!

26

But only Caucasian lands? Certainly not, I hope!

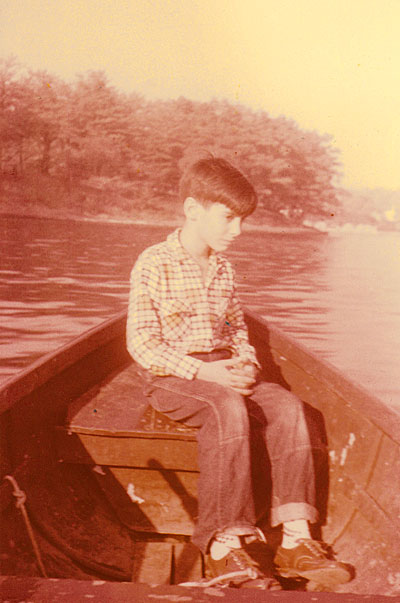

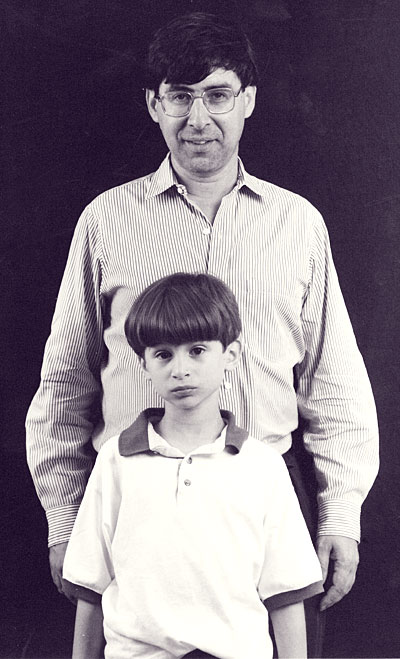

David Shapiro, sitting on the poles at Deal, l965, photo by Julia Van Haaften

27

As you know, I know the least about Latin America except that I met Borges and tried to memorize whatever I could of him, of Bioy Casares, and though invited to Cuba by Fidel’s friends in 1968, I was still too provincial to go. Nor do I know more than a month of China. India I still have to understand, but Lindsay at least supplied me with what she learned from the great Indian scholar, who replenished Philadelphia’s collections, Stella Kramrisch. I also studied, because of Meyer Schapiro’s love of the East, Japanese in Princeton for a year with the head of the Freer, Shimizu. I learned again and again that I knew nothing. Meyer would begin a semester about theory with the scandal that Ruskin said of the East: those who have no art. “Blindness” like that provides a central insight: we are all blind. We are rescued by a few who revolutionize taste. But to have this change involves a dense cultural and social series of oscillations. Pound can escape into a non-sentimental Tang world in Cathay, but his other bigotries remain and stain.

28

Very well, then. But what of, shall we say, Marcuse? I seem to recall you saying something once about Marcuse.

29

Marcuse’s stepson and I wanted to introduce and failed to have a large slice of Hegel in the curriculum of the language-philosophers at Cambridge University in 1968‒70. It didn’t work. We were too new, too American, too arrogant to inflect. Raymond Williams and Leavis passed by like young and old ghosts. I had two years in which all I did was worry about my fiancée and study as many novels as I could from Clarissa to Middlemarch, because I had the time. I went in the mornings and left at the latest minute. I even ate in the library. Yes, sandwiches and the 19th century women novelists. I even gave a concert that was called “An evening of Jewish music with David Shapiro.” I also played in a Stockhausen group with Smalley and others. The rules were: Take a note. Match your neighbor’s note. Turn it into gold. Very loud music. Sir Leach left it quailing about loudness. One musician showed me he was carrying ear-plugs.

30

But surely there were rules against eating in the library? Though I do want to ask you about your music later…

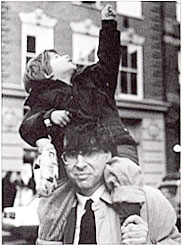

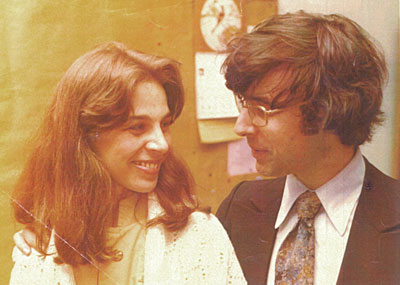

David Shapiro with child

31

I did eat in the Cambridge Library, but by permission. Some genius had decided that reading should not pause for hygiene. Is it dirty? Is it a library? It is dirty and a library. New York is a library, said Pellizzi, an empty center. Paz said to me with endless pathos and restraint: You will find everything in Eliot and Pound except any allusion to Mexico or Latin America. I found the River Platte somewhere in Sweeney but patently no real attention to that other world. But Williams says, and it inspires me as much as the plum and Queen Anne’s Lace of sensuous white ― Williams says he called his poem “El Hombre” because he was fed up with the French titles of his confrères. I had never noted that. But now I have had my years of thinking of Góngora and Quevedo. Borges told me he had learned his English from John Wayne and the westerns. He teased me until he realized I had memorized even his prose (“The Aleph”). Recently, Jasper Johns told me he was memorizing the poems of Borges. When I asked Borges what he thought of chance techniques, he dazzled me by saying: Randomness leads to vanity. He was a good example of the integrity that takes the false avant-garde and wrings its neck as strongly as Rimbaud wrung the neck of the rhetoric he despised.

32

There are so many names when you speak. Off the top of my head: Wallace Stevens?

33

If I refer to names, it is because of what I hope is the humility of Jews. We quote, but not in the past tense. Richard Kostelanetz asked me on the street once: Who is your favorite living poet, David?

— Decades ago, I said Wallace Stevens.

— He said: But he is dead.

— I said: But not for me!

34

I simply think reading Stevens is one of the paradises that constitutes reading. I wrote a little pamphlet about him once with pictures by Goldberg. What I particularly love, not just the paronomasia, is the feeling-tone of suffering, as if he could touch and write, every way. His poetry is towards a supreme fiction but never gets there. That’s why it is Bach-like to hear him courageous about the fact that Penelope and Ulysses don’t meet, or get halfway there.

35

Marvelous.Let’s say that I asked you to extend the following into an observation of some kind: “It is said a poet showed his library to a taxi driver… ”

36

It is said a poet showed his library to a taxi driver, who then said: But I notice that all your books are in one language!

37

It is the macaronic that is dazzling in our time as in Pound’s rhymes of many languages. Tó Kalón and “tin wreath upon” [4] Or: “Oh whitebreasted marten goddammit since no one else will carry the letter tell to La Caro Amo.” So many levels and perspectives of language.

38

The global and the local will oscillate in these years as our “collection of tensions.” But Jacques Derrida is right in a last beautiful conversation on Islam to remind us of the horrors of false globalism and its sentimentalities that crush. Simone Weil often wrote about the dangers of the Roman Empire. It gave us straight streets and good plumbing, but it also disrupted and destroyed so many of the “minor” languages. We are not marginal, as Jeremy Gilbert-Rolfe said to me once, because we could only be marginal if there were a center. There is no center. We have all loved New York, “like the bathroom,” or a time of suffering (Koch), but we are all fleeing it now.

39

Could you talk a bit about some touristy things you have done? Have you ever been to Israel? Do you know the poets there?

40

I had one guide for months in Europe, who took me to little important places from Arezzo to Siena and the Alps and southern France. Later did the Loire with his family and my wife, Lindsay. I wasted my time not going to Israel when I was invited by my relatives. But now I’ve been there and know the poets there. At least one is worthy of a Nobel: Schimmel, one of the ten best artists of the Hebrew language. He should share it with a great Palestinian.

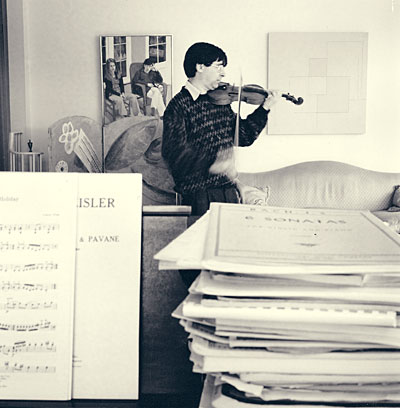

David Shapiro with violin, photo by Laurie Lambrecht

41

So it looks like I know something or knew people, but all I knew was desecrated by my lack of final touches in harmony and theory and not copying for Virgil Thompson, because I had to sleep with him. I had the best violin teachers, but I didn’t have the love of 8 hrs a day of brutal practice. At least I had private conversation with Stokowsky but never with Gould, with Said but never with Foucault, with Kristeva but never with Deleuze. I was lucky to see Octavio Paz on a regular basis for a while with Francesco Pellizzi, with whom I was helping with the anthropological magazine RES. Pellizzi had done a great deal of work on the soul in Chiapas. He also founded a textile museum, so with him I learned a great deal about the mask, anthropology, and the cosmos in textiles. Francesco also helped edit Adelphi books, and his father was a close friend of Pound. His mother told Francesco, when he was leaving for his fieldwork in Mexico and elsewhere: You are leaving for Mexico, but you don’t even understand the women who work in your kitchen! He also gave me a rather Bolaño-like line, when he quoted a scientist as saying: “I am afraid of nothing. I have been to Mexico.”

42

Excuse me, but did you just say you slept with Virgil Thompson? Tell us more about that, please. And as you do, could you talk about music, too?

43

I did not become intimate with Virgil Thompson, though I continued to read him and listen to him. There had been a joke of whether I could be his student and copyist without “relations.” Ha! His settings of Koch and Stein and other poets are some of the best, and I also care for the movie music, horrible locution, he made. I never agreed with him that Heifetz was “silk underwear” music, but I think he was trying to inflect a little the idol-worshipping of Heifetz. Heifetz was trying too hard to make no mistakes, whereas Shaw asked him to make a few.

44

Rubenstein said I have to practice; Americans hate mistakes and like machines. Friends ask me when I gave up music―I haven’t. I’ve come to a place where the acrobatics and ice-skating of musical practice no longer lure me. I hated those who forced me to play the music I did not want to play, and teachers quite well-known, who didn’t have any sympathy for 20th-century repertoire. I admire Paul Zukofsky for simply carving another route. Koch always reminded me of Heifetz ― the absolute steely exigency of Kenneth’s poems. It seems as if he could have been locked up to finish a complete Ovid. There is nothing better than to think of his translating Ovid entirely. (Or Williams doing Lucretius, as he sometimes warmed to that.) Wilbur, même, could be locked up, as I told him, just to do Molière. And the footnotes to the Montale of Arrowsmith are better than the translations, but which at least are clean. And Pavese is so well-done by the same. But the act of translation is so difficult that it seems to be the essential complex human activity: how we speak to the Other despite the fact that all is mistranslation. And yet.

David Shapiro with his son. Photo Rudy Burckhardt.

45

Yes, translation is always so much about that “and yet… ” And yet, mistranslation as purposeful art can be as mysterious as the accidental kind. I have a friend in Chile, a brilliant poet and critic, who wrote some weeks ago to tell me he was mistranslating ― traslucinando, he calls it ― Elizabeth Bishop. “I am in the process of discovering my loss in her,” he said.

46

Well, in fact, recently I have been comparing Bishop’s “One Art” to Saba’s amazing poem about losing everything. Saba’s is political, against Nazis and Fascists, but for long stretches it is about losing lovely cities. Just as I recently decoded the James Dean poems of Frank ― at least one of them fairly literally ― as a translation-homage to the Rückert song in Mahler: I have lost touch with the world. Isn’t it amazing how these little discoveries flatter ourselves, but the important thing is to read even more than writing: a mysterious phrase, as Bolaño often says. It means not to judge art by our tiny contributions.

47

You like this Mr Bolaño, eh?

48

I have to say I cannot find a recent American author except for De Lillo and Pynchon ― perhaps that’s enough with Roth developing so much ― as resisting and sensuous and wounded as Bolaño. I can’t find this in the translated poems, but I love Nazi Literature in the Americas and the absolute greatness of the chapter on murdered and disappeared women in the posthumous masterpiece. Bolaño doesn’t just cheer me up, he shows what truth-telling could be in our time. Like knowing what Louis Kahn could build in Texas in the 1970s. Like knowing what Jasper Johns could paint, at what a height, in the last fifty years. A tremulo that went through me, as I read the typed mss. of “The Skaters” and could not find a wrong “note.”

49

But when the Nobel committee speaks of provinciality, I cringe. What has been more absolutely provincial than the choices ― some just rumored, some only delayed of the Nobel. If one wants to make the case AGAINST the global, if one wants to say Bolaño was only Chilean, if one wants to say that Borges was a reactionary ― all this would be untrue if interesting for a second. I was thinking since 1967 that Ashbery was the best poet working and alive in any language I knew. And the Nobel is talking in a century in which they did not honor the gods Proust and Joyce, Rene Char and Freud himself. Ha! But this is an old argument. I wrote a book on Ashbery and hoped to help him out of neglect. Did it work? Most would say that it took a few professors to make the argument for John. I might say arrogantly that I have learned nothing new about John from the critics ― sometimes from a remark or two that John drops strangely.

50

No, I did not become Virgil’s copyist, and my calligraphy is not subtle. But I spent my life listening to Mozart’s late Divertimenti with Heifetz, Primrose, and Feuermann. It is fine with me to have sung the melody of the Andante to my child day one, hour one. My dream is that I am not, as Koethe once called me, a miniaturist, but I might have to write 100 pages called “The Miniaturist,” because I am interested in questions of scale. Koethe relented and said I was more like chamber music. Yes, I have always admired the chamber literature above the symphonic. That is my flaw, though I try to correct it.

51

You are a master violinist. How do you, if you do, separate music from poetry?

52

I would like to say there is no discontinuity. Every word rises to me like the Russian’s formulation of consciousness. I can’t imagine a poet for whom synonyms are ever truly synonyms. Each word dives in like the canonic frog. When I told E.M. Forster that I was giving up music, he stopped me by saying in a very moral adagio: I FAIL TO SEE… .HOW ANYONE… .CAN GIVE UP… MUSIC.” That stopped me. I wrote most of my poems to and from and after music. I know for some it’s a sentimental way. But even now I would like to write a hundred songs for Heine and Sinéad O’Connor or Kiri. Anyway, like architecture, the structure of music is so close to poetry. Foss told me, “You poets think that we care about the texts.” But of course Schubert does, that “whole mismanaged mess.” Imagine Frank O’Hara without his brave love for Rachmaninoff. Imagine Proust without the little melody. And when I found that the Saint-Saens sonata number 1 for violin and piano was the matrix of the little melody, I quavered because the melody, exactly as Proust says, is fairly trivial at first. After a few days of practicing, it had become the national anthem of all my poetry, also. I had thought previously that it might have been the César Franck or the Faure, but no, it is this little subversive thing that he used to play in four hands with Renaldo Hahn, his great friend.

53

I don’t know very much about music, but I love M. Satie, the piano music. Do you? I think of Mr Ashbery when I listen to him. Is that naive of me? What NY School poet do you think M. Satie most resembles?

54

My answer is possibly too obvious: Cage, who loved Satie and organized marathon Vexation concerts, is the philosopher-musician of our time. John A. said he was inspired by the simultaneous radio concert. It gave him “permission,” like Pollock. Cage’s early pieces are like the pastels or veils of Rauschenberg. Kenneth used to quote Cage in class all the time and hilariously. If a person were to know all the music of Cage and Morty Feldman and how they composed, and what they learnt from say gamelan and Debussy, from Webern and from Indian music, you would be well on your way to understanding NY School poets, some who would gently say, “here.” And all of what Adorno hated in jazz and rock.

David Shapiro with his son Daniel, 1995, photo by Bill Beckley

55

John A. has eccentric tastes in music and his love of Busoni is an example of where that taste is refined and right. Kenneth’s sense of music was sometimes bizarrely innocent, and he loved opera in its melodramatic verve. Frank O’Hara simply was an American musician, and when he spoke of music, or dance, his precision was obvious. Of course, it may seem to some that Frank was romantically campy, but not in his taste for music, and some would say not in painting. Kenneth once said of Pop Art, “David, don’t you think it’s naïve, say, of Warhol to put a live rat between the pages of a book.” My favorite pieces by Cage are “Cheap Imitation,” “String Quartet # l,” and “Six Melodies for the Violin.” Morty, at the end, could do 5 hour pieces that are the most erotic monochrome in the world. I have tried to imitate that effect. JA gets it in his long Three Poems. Or Litany. Imagine an opera with John’s words and Morty’s music. Morty and I did do a little chamber opera with Hejduk, but no one seems to have heard it at the Boston ICA.

56

When I am bored, say, waiting for a bus, I play John’s “Silence” in my head and pay attention to the most quiet sounds. My happiest moments used to be listening to “Indeterminacies” with David Tudor’s chord clusters outside, in the park. Cage knew I wasn’t following him religiously, but he accepted parts of me, I think. At night, at Columbia, I would hear minimalist music and drumming beginning to be transmitted onto the campus. My tastes were begun at 0‒5 through Beethoven, Mozart, Bach, and later by Shostakovich’s quartets (say 4 and 8) and Bartok and Webern to John Cage. Ciccolini alone I would wake up for in the AM at the university library and listen to him on “Gymnopédies.” I described Satie at the time as ice cubes of glass breaking and played perfectly backward.

57

Thank you. Now, I know that philosophy has been important to you, as well, and not in a casual way. For example, you studied symbolic logic at Columbia, which I think was taught by the President whose office chair you occupy in the now fabled photograph from Time and Life, where you are smoking a cigar…

58

In philosophy it turned out I mostly cared for aesthetics and not for symbolic logic. I knew Nagel thru Meyer. But I am weak in Husserl and love Merleau-Ponty perhaps too much (Cézanne). I never met Camus, Sartre, de Beauvoir. I learned my Hegel by reading hard

59

Kojève for some years. I was drawn to Hegel as to Melville, and I loved Hölderlin’s connections. The Phenomenology of Spirit is to me a great novel and to be read that way. Danto once said that poet-art-critics were replaced by philosophers in our time. I said that if Vico were correct the poets would return. He satirically said that the philosophers would, also. There is a plane, as Wittgenstein seemed to know better than anyone, on which music and philosophy and a poetics are simultaneous and the same. But to reach this allegorical plane is a tumult and a famous blur. Deleuze reaches for this in the basic philosophy text, where he argues for philosophy as an experience like the painting of Bacon, and without this experience of no aboutness one does not know the baroque folds of philosophy. But here many are lost, hic sunt Dragons and lacunae, because of the bad poetry, the night of Shelling, as Hegel said, in which all cows are black.

60

Of M. Camus, M. Sartre, and Mme de Beauvoir, none of whom you met, as you say, which of them would you have most liked to meet, and why?

61

Actually, I was having my hair cut one day in Paris, and it turned out the barber was Sartre’s hair stylist (haha.) I told him, as if he didn’t know, that I was so impressed by Sartre turning down the Nobel Prize. He went on clipping , as he murmured, with enormous clarity: Un geste enorme.

62

I think Merleau-Ponty would be the one I wanted to meet, and to take a walk with Debord, whose cartoons and screenplays of darkness I felt close to after our own événements. Meyer thought the best philosophical writing on Cézanne was Merleau-Ponty, but he also thought that Merleau-Ponty wasn’t specific or historical enough. One can’t talk of Cézanne; one must talk of his development in specific canvasses. That is the failing of so many critics who act as if Ashbery or Stevens are static quantities.

63

Hm. More on this static quantities thing later… Was Philosophy hard for you, or une brise?

64

Philosophy at Columbia was difficult for me, because it reiterated the sense that the epistemological and symbolic logic above all ― was all. I was so hated by one younger assistant professor. Oh, where is he now? But I would bring up the irony that Plato was exiling poetry and the poetic but was doing it in golden dialogues. The professor shrank with sarcasm and rage: “Mr. Shapiro, if you bring up once more the specter of the lyrical Plato, I will have to urge you to leave this classroom.” I was dumbfounded, because I was always so intrigued by the dialogues as dramatic or set-ups or indeed nothing but aporias in their hold. I always thought it was to the greater glory of the NY School of Poets that we had for so long no critique. No truth, no ultimate truth. Not like a sixth-grade teacher who urges one to find (row A) the world truths in Act I of Coriolanus.

65

Say unfolding folds are the rage of Socrates at finding no flute-teacher worthy of the name. The poets rage, because they cannot see anything but the shadows. The philosophers rage, because they see nothing but precise lighting conditions. The poets are satisfied with shadows. The philosophers think perfect pitch is Lord Berkeley. Danto told me once he didn’t believe in pluralism, because there was a truth. But later he vacillated and called “objective pluralism” the truth. Well, that is what I meant. At the least, we dwell in a world of many truths or we think others are scoundrels with their diagonals. Pluralism is not just a stylistic pathos. It is our cities of refuge.

66

Perhaps it’s a leap from what you just said, but don’t you think the NY School poets, you included, though you were very young, sensed a shadow of sorts, were on to something before the philosophers who were soon to be all the rage? Perhaps this relates back to your comment of how the critics tend to treat Mr Ashbery and Mr Stevens. Too bad Mr Derrida never really had a go at Mr Ashbery…

67

I always was dazzled that there was a turn toward treating the NY School as if it had one stable metaphysical aspect. Ashbery asked me once, do I have to read Derrida, David? I assured him that he already was practicing whatever Jacques wanted of close reading. Imagine urging Kafka to read Canetti, say. Who comes first, John or Jacques? I always teased Jacques that he was secretly a Jewish poet. Then his son changed his name and wrote poetry. It wasn’t as good as his father’s “poetry” that was no poetry. Note all that was cadenza in Jacques’s readings of Blanchot. And is there no better poet in our day than Bataille on gifts?

68

I reread Jacques and remember that one day I told him how little Peter Eisenman cared for poetry, and that he had told me ― Peter ― that poetry was just rhymed idiocy. Jacques smiled and said: You are presuming that he has ever read me. The last documentary about him breaks me in little pieces, as when he keeps saying to the students, “You can’t ask me that (What is love), no, you cannot.” Then he says: “But let me tell you what you might, might want to ask me: ‘Does one love someone for the who, or the what?’” He and his wife refuse at first almost all familial questions.

69

And so besides Mr Derrida, with whom you wrote a book, and the young assistant professor who hated you, with whom did you study the Philosophers?

70

I studied privately throughout my life with those who interested me as philosophers. My aesthetics and my belief in the strangeness of the word “beauty” in different cultures come out of Meyer, who called himself the student of Dewey. I took 30 years of psychoanalysis, group therapy, psychoanalytic seminars, because though I was skeptical in the way Wittgenstein was of Freud’s seductive anti-logic, I felt that it was one of the best rhetorics about “splitting” that we had after Hegel. An anthropologist who used psychoanalysis said, “This is the best we have, David. There are no shamans.” But note, aside from the efflorescence of Lacanism and French Freud in the New York “area,” that only a few literary critics had become thoroughly at ease with the Freudian project: Norman O Brown, Rieff, perhaps Bloom, etc. There is a decided will to stupidity in Crews’s anti-Freudian positivism. I presume he would rush himself to a therapist if he recovered the memory of how philistine his essays are. Indeed, I can imagine no higher compliment than the attacks on Lacan. I once read Wollheim against Lacan and thought it the final Cambridgian lance against what was thought of as ingenious thought. Meyer said he got along with Breton the dogmatist, because he changed his dogmas every week.

71

Here’s a good reading list, by the by: Read everything Pound recommends. Then read everything else, including Wordsworth and Pindar. Now, again, read all the books of Meyer Schapiro, then read all the work he footnotes. This was my useful path.

72

But M. Lacan was truly mad, don’t you think? And his student Mr Žižek is even more a loony tunes, for sure.

73

Meyer Schapiro told me he thought Lacan was a genius if mad. But he was fâché with Jacques D. because of the accusation of a minor positivism against him in Restitutions. Jacques admitted to me he had not known the full scope of Meyer’s work. He is weakest on painting, anyway. Žižek has recently written some very lucid works against torture and, most of all, against even permitting speech about it. A very noble position. He said, “We don’t speak about the times when rape would be possible.”

74

Yes, then again, the anti-torture Mr Žižek seems at moral ease with the notion of the guillotine. A rather schizophrenic ethics of Terror, though I suppose he would say I entirely miss his dialectic. But speaking of the Age of Reason, what do you think about the Great Books curriculum at Columbia, with which you have been so intimate? Who are your preferred among the Greats?

75

I have learned the most no doubt by teaching the famous Humanities Great Books for a decade at Columbia. It would be as if each year one had to play the 20 most intricately beautiful violin concerti. It took me even more than 10 readings to find myself becoming utterly involved with Don Quixote. My true Penelope however is Proust and Kafka together. How sad that Jacques , like Sylvia Beach, as your magical letter seems to reveal, never became a Proust-reader.

76

If the Jewish God doesn’t contain room for Proust and Kafka, then I could not be monotheistic. Kafka and Proust as I grow older, grow larger ― the starless chaos of the interior and the starry chaos of the social kaleidoscope.

77

The Blue Octavo Notebooks of Kafka is the training ground for whatever ice I axe. Proust to me (not to some, amazingly) is the great Jewish prophet (E. Wilson felt this), and every sentence is the annihilation of anti-Semitism. The snob that everyone accuses Proust of being was pretty much his mortal target when he withdrew to write. The dream of his grandmother is the best surrealism, and to think Breton did some of his proofing. I find Proust and Kafka are the great comedians of the century with Machado de Assis, Chaplin, Keaton, and others.

78

Kenneth Koch loved giving his course on the Comic, but he told me refused to do an anthology of humor as with Ogden Nash, because nothing was less humorous than an anthology of humor. But Kenneth is a Jewish comedian even when he’s being his own inveterate godless Jew from Cincinnati. He took out the word God, the priest told me, from every portion of his second marriage; I knew something was strange and fresh about the service. He was glad I introduced him to Kawabata, Braudel, and Benjamin, and Shklovsky, but he refused any religious text I tried to give him. Even when I told him Bialik’s stories of Talmud were Kafkaesque, he rejected that book utterly and strangely (to me).He was a devout skeptic.

79

Of Žižek let me say that he is obviously a finesse of the higher or lower obscurities, but I saw this year that raw and right disclaimer against torture. He suggests that even talking of whether torture is legitimate is terrible. We are finally barbarians if we even permit ourselves the conversation. I thought this better than most of his work about Stalin or Hitchcock, but it proved to me that he is capable of mordant truth. The rest is rhetoric. I always refer to him as the immortal Žižek, because he functions as a Wizard of Oz. Jews tend to be skeptical of such Marvels..Žižek reminds me of the surrealists when they were always excommunicating each other.

80

But I too am in surrealism:“You are standing on my eyelids,” for example, is a standard with me of how to wake up. I made a huge reading list recently in the Poet’s Bookshelf #2. You might think it a mad permissiveness. I hate the critics of poetry when they are themselves the brutal policeman of what they think is a game. I would say I have culled this lesson from many: Art is not a dream, not a game; it is of course the biggest and the game that outlives empires. When I heard Bobby Fischer trying to change the rules of chess, I thought: What a Rimbaud even to consider it! They ruined baseball didn’t they? But Sartre was told: Never, never attack baseball.

81

Really?! What did M. Sartre reply? Did he really once attack baseball?

82

All I know, and I think I know it from some memoirs of the later Neo-Con Lionel Abel, was that somehow Sartre was having a glamorous tour here, but lurched into an anti-sports mode that included baseball. Borges, later, chose the diplomatic mode: Baseball is a metaphysical game, because it need not end.

83

So speaking of politics… Your radical past, its relation to your teaching, and also, perhaps, more about psychoanalysis, which you are not shy of saying you know well, etc…

84

All I did politically was a caricatural gesture and helping to embarrass McNamara wherever I could. The only minor agitator I knew was Hayden and the Weather group that grew out of the action faction I allied myself to. I taught for three decades trying to teach another course each time, particularly at Columbia, so they would guess I was a good citizen and truly would teach anything. I think I’ve taught 30 or more courses.

85

My father’s medical secretary, I tried to learn dermatology from my father. But 30 years in psychoanalysis I think was the most helpful: I tried group therapy, cognitive therapy, Freudian, etc. I knew Lacanians here and there. And met Lacan’s own analyst, Rudy Lowenstein. I was in a psychoanalytic group where I was the layman. Eriksonians. I could not imagine analysis without Reich’s brilliant and coruscating hymn, that he had become an analyst not because he was sick alone, not because some in Germany were sick, but because he looked through Germany and the world and discovered that everyone was ILL. Meyer Schapiro learned from Rank. Once, when I questioned him about the rage against icons in Conceptual art, he said: “Where there is the war against icons, there is much pornography.” He saw it in explosive marginalia. He was unashamed of the erotic and saw it everywhere.

86

The erotic. Well, you knew Kenneth Koch, as you have said, the humorous and erotic poet, who was a friend of Mr O’Hara and Mr Ashbery. The three of them, along with Jeremy Schuyler, as you know, formed the avant-garde group that has come to be known as The New York School of Poets, and I believe some studies have been written on this. They had some associations with the most experimental painters of the period, the so-called Abstract Expressionists, who were, I read once in Reader’s Digest, used by the CIA for purposes of cultural propaganda.

87

So my question is, what was Mr Koch like, and do you know if the New York School Poets have ever been used by the CIA for cultural propaganda purposes also? Also, whom do you favor: the Formalist Mr Greenberg, or the Spiritual Mr Rosenberg?

88

You mean Jimmy Schuyler, of course.

89

Oh dear. Yes. Well, your answer…

90

Kenneth Koch was urbane and probably drove me to meet as many poets as I could in any given place. And to be a great reader and athlete of writing! He wrote without ceasing. He was clear when he was in love, he said. His comic epics rival anyone after Auden. He took analysis and used it. He took surrealism and squeezed upon it an everyday surrealism. He was a great teacher, and he believed in teaching. He gave confidence and was called the Charles Atlas of his own students.

91

He cared about prose and his prose is underestimated. He despised religious texts, and that was his own great religion. He divorced himself from the poets now called “quietists.” But he could suddenly sting one with an acceptance of a poet one might not have been convinced in reading. His taste for Supervielle is not just a passing whimsy. He knew and loved his students when they were completely committed to Poetry.

92

He was a playwright, who knew the stage was like a page. Anything could be done upon it. He never gave up. In his last great illness, he taught while he was surrounded by anti-bacterial screens. He gave a reading a week before he died and was feisty about certain facts. He was a brilliant presence, but he was better than anyone knew about this brilliance. He was noble, and note the melancholy throughout his work. I have hundreds of pages to write about him. He was a divine comedian, who knew how significant the comic was.

93

Even his assignments were poems: to write Hamlet’s first scene without rereading it. To write a short story that could be read in two or three ways. To imitate. To dislocate. To be shameless. Not to write, as he told me, any bad books. He was devoted to poetry and languages he loved. He did not stutter in the foreign languages. He treated English as a mysterious language. He loved Rimbaud utterly. He loved Italy and adored travel. He loved translation and mistranslation both. He was faithful to his students. He once compared a large tree to an ancient stanza form, says J. Harrison, a student. He gave one the uncanny sense that even in college one could create a masterpiece.

94

His students often never wrote as well as in his classroom, but that is a phenomenon well-known. He wanted to make movies. His ambition was limitless. His taste was so refined. He said to me when I was 15: Muir is part of the history of sensibility but not of poetry. He spent his life partly praising Frank O’Hara and John Ashbery. Without him, not the professors commonly cited, these poets would never have had the same career. He was, in that sense, as generous as Frank or anyone. His exuberance was lofty.

95

He reinvented the essay-poem and the ode. He could speak to a cloud. He hated false political dogmatists and told them ― like me ― to their face, “Be revolutionary but also be witty.” He was witty and had the perfect pitch of humor. He taught three generations how to associate freely. He wrote the most advanced “language” poem a generation before they were born: “When the Sun Tries to Go On.” He is so vast it will take another generation to digest him.

96

That’s very beautiful. I wish I had met him, at least once. And Mr O’Hara, too, of course. But you had meditated a bit on the Nobel Prize. Why has no New York School poet won the Nobel Prize? For example, one would think that Mr Ashbery, who has been translated into Nepalese, even, would have won it by now!

97

I believe that John deserves the Nobel Prize but is too subtle and refined to win it. I was amazed throughout my life how long it took for John to be recognized and even loved. Frank’s ardor helped him be understood and his wild particularity. Jimmy happened to be obviously one of the greatest Nature poets there was. He was in love with roses the way as the Bible says a man looks at a woman. I still look forward to seeing all the photos by Jimmy and also to a book on Schuyler and Porter. Someone is already working on that as a Master’s. His elegy to Frank is a perfect poem. Anyway, my father said he was a footnote in the history of dermatology. And I am hoping I will be a footnote to American pluralism and the New York poets, who never treated me with contempt. It took latecomers to do that.

David Shapiro, photo by Bill Beckley

98

Yes, many of us have felt “disappeared,” as Silliman said of Joe Ceravolo. In one hundred books by the language poets you will find zero mention of poets who taught them, like Bernadette Mayer or who were close to them, like Charles North, etc. But the whining must cease and the lament. It will be up to s ubtle critics to see and calculate what was done and by whom and what is vital beyond any trivial idea of form.

99

Singer said, “Anyone interested in winning the Nobel doesn’t deserve it.” So let’s forget it in the most squeamish way. I was amazed when two of the recent poets pretended that if anything they felt there had been a delay in granting it. The equivalent of 10 Prizes is to change the poetry of two to three generations, like Williams, Stevens, and Pound with all his stains. In science, Cathay alone would be enough to force a Prize.

100

But do you not entertain, Mr Shapiro, that contingent erasures in the poetic field, the politically motivated ones, the transparently calculated ones, can be vital, too? I am thinking, just for one example, of your weird disparition from the Carcanet anthology of New York poets, published not long ago in England, so over-the-top, so hilarious. That must have been an irritation, I imagine. But literary history has its mysterious ways of offering recompense, doesn’t it, often and unpredictably so. Might these slights, in that sense, not prove to be a kind of gift in disguise? Something to be thankful for? Do I make any sense to you?

101

I joked that I didn’t mind being left out of anthologies. But I had never had the experience of being left out of my own. I am proud that almost every choice I made as a young (15-year-old) kid I thought of a volume of these neglected poets: Koch, O’Hara, Ceravolo, Denby, Guest, etc. The volume as it ended up is not what I would have created alone. But Ron Padgett has his own eccentric tastes. Maybe being left out, as it were, is a sign of being punished for no longer remaining one of “the group.”

102

Yes, I do get swept up like anyone in the bitterness of poetry. Luckily, there is the sweet-bitterness of love and one’s family and poetry itself. If I were on the famous deserted island, I would want only a chance to read and to write for that famous slipped-away addressee. Anyway, better to be wise than bitter. E.M. Forster who so moved me in his late years at Cambridge said of Ackerley, master of the novel of dogs, when he was treated badly by the BBC ― Forster said, burning it into me, How badly… people… DO… behave.” The lesson was condensed; two cheers or more for such democracy; he told Eliot off when Eliot chose to depose Lawrence at his death. There are times, said Forster, when I would rather be the fly not the spider.

103

Auden made some terribly loutish praises, as for Phyllis McGinley. It was his way of abandoning the younger poets to their own matches. Fine, but then he could have kept quiet rather than writing, for example, a disdainful intro to Some Trees. But let it pass like a friendly ghost. I saw Auden once wearing sunglasses in a Church. That was a collage! I love early Auden; Kenneth loved the lines, “Now is the time for the destruction of error.” So grand and so democratic. The communard in early Auden.

104

I believe I may have interrupted you with my question about Mr Ashbery and the Nobel, a little before. So what else might you say about the debonair poet, Mr Koch? And please answer my question about Mr Greenberg, Mr Rosenberg, and also the stuff about the CIA…

105

Kenneth Koch was urbane and probably drove me to meet as many poets as I could in any given place. I remember asking Meyer Schapiro what he thought of the analysis of the relations between jazz, Ab Ex, and the CIA. He thought it was nonsense. Remember, it is one thing to have Peter Matthiessen admitting that he was somehow in cahoots with some interestingly imperial forces, or the moment when Spender and others admitted Encounter had been used. But the painting of the Ab Ex had absolutely no relationship to cultural imperialism, or it is so vanishingly little that it might compare to any cultural phenomenon at all in an Empire somehow dislocating the shoulder of those not involved at all in the Roman Empire.

106

I don’t think it’s a difficult argument to make; it is simply overwhelmingly vulgar Marxism. What would be a more interesting thesis would be to reveal, like Adorno, a hidden dialectic always between modernism and social fate. Adorno on the music business comes close to being his most vulgar work, and not in the beautiful sense of ‘vulgar’. I think Koch once told me that he had become a Trotskyite after the Second World War. He had decided after this period that he had a responsibility to list and celebrate all the pleasures of the world in a drive toward what he thought of as a rational hedonism.

107

This wild hedonism actually led him, as he knew it, to a fairly painful condition. He used psychoanalysis throughout much of his life, but he joked that his terrible stutter was one of the things psychoanalysis had cured or diminished. I do think he learned from the dreams analyzed by Freud and by keeping aware of his own dream life. He was very rational about accepting the irrational. His extreme irrational was rational, to reverse Stevens through Serge.

108

So Messrs. Greenberg and Rosenberg…

109

Greenberg and Rosenberg: a book will be needed to correct the lack of subtlety in most of the discussions of the two. Steinberg was included, I think, in the Painted Word by the illiterate aesthetician Tom Wolfe, who tried to bind these all in a kind of derogatory Berg-stream. I would add:

110

Clement Greenberg:

111

Harold Rosenberg:

112

Greenberg and Rosenberg have lost their influence, and Steinberg’s work is more truly learned. Steinberg has become a connoisseur of Leonardo and Michelangelo. His work on late Michelangelo is brilliant. I do not accept his thesis that Christ’s sexuality is the visual center and thematic of many paintings of the 15th century. He rides a hobbyhorse, and I do not believe his arguments of erection-resurrection and the breezes flying. The same breezes and storms affect the good and bad thieves, said Meyer Schapiro to me.

113

The critics evaluated before judgment. When I became the art critic on the doomed last boats of Mr Shawn’s New Yorker, I admitted to Meyer that I was worried about issuing negative criticism. He said: “Bernard Shaw (!) said if a man can’t be a journalist he can’t write. But: try to comprehend before you evaluate.”

114

Qualifications taken into account, you were perhaps importantly influenced in your art criticism, then, by Mr Rosenberg?

115

The critics of my day did not influence me as much as the great art historian and his appreciation of Mexican art and even his subtle critique of surrealism. That even the dreams of a culture are social. Meyer was my God, and I was a monotheist! About pluralism he told me: The one thing pluralism or eclecticism cannot contain are the advantages of purity.

116

In Israel I just completed a text with and for the artist Tsibi Geva. His work is difficult for most, because it is both of the Kibbutz in which he was born and the world of New York, where he also studied at the Studio School. Meanings are not stable. A spray of paint may seem very much out of Pollock, but it is also an allusion to harps hung on trees in Psalm 137. His mountains are mountains of surrealism, like Mt. Analogue of Daumal, but they are also mountains which he circled in the army. This “collection of tensions” again gives the audience in Israel a mountain shock of polysemy.

117

Everyone is comfortable with getting the same experience over and over, like McDonald’s society in which the food tastes identical wherever you go. But the profound frustration experienced in Tsibi’s work is that of having a center and a margin both and both changing in a new Baroque. Also, he is not tied to any particular medium or iconography. Birds, beasts, and flowers are themes of his work, but also suddenly an architecture that derives from his father, who built even without a license many important buildings. It is also impossible for many to escape the political in the topoi of his work, which include Arabic collaborations and constructions in wood that seem to bear many possible nuances of the social in a time of the Wall.

118

The artist at 57 is beginning to be understood in a new giant show in Tel Aviv. There is a delay in glass, as it were, for the multivalent artist.

David Shapiro lives surrounded by art and music. Photo by Claudio Papapietro for the Riverdale Press, copyright © Claudio Papapietro and the Riverdale Press, 2009. Used with permission.

119

The great influence for me has always been the artist in her studio. Talking in front of the painter. Fairfield Porter’s critique is good, because it is in favor of the analogy, of the short review, of the honest struggle with historicism, and the lack of a surrender to the monist critics.

120

I helped a bit on the book of his letters and of his criticism. His formula was no formula, he was against method. He said: “I would like every sermon, David, to end with these words: Pay attention, pay attention to Ultimate Reality.” But Ashbery had teased him, and he had said: “What does ‘ultimate’ mean, Fairfield?” I said John is often religious when he pays attention to the outsides of things.

121

“That’s it,” said Fairfield, a few days before he sank gently to his death on the lawns of Southampton. “That’s it. It’s not behind everything; it is everything!” I am glad I took that early morning walk with Fairfield a few days before his death in 1975. The priest said he had been a master of light and repose. He indeed loved light, but he was also a lover of liberty and surprise. Greenberg ignored him. Rosenberg knew him but not clearly. Ashbery understood and praised him. The painters like de Kooning loved him.

122

Porter painted Frank O’Hara. And I must ask you now about the great poet, of course. He was a deeply crucial teacher for you in your early years. You knew him well. So, what was Mr O’Hara like?

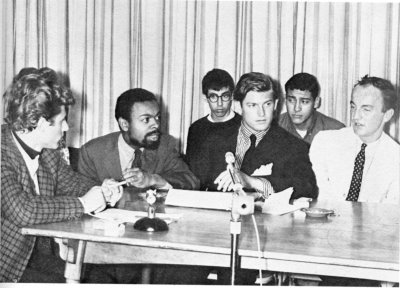

Gerard Malanga, LeRoi Jones, David Shapiro, Bill Berkson, Frank Lima, and Frank O’Hara at Wagner College, 1962, photograph by William T. Wood, from Berkson, Bill, and Joe LeSueur (eds), Homage to Frank O’Hara. Berkeley: Creative Book Company, 1980. p129.

123

I had loved Frank O’Hara’s poems as soon as I memorized them in 1960–61 in the Donald Allen anthology, which I think I picked up at the Gotham. I was embarrassed reading it one summer day because of the lines: “Yippee I’m glad I’m alive I’m glad you’re alive too baby because I want to fuck you… “ I told Brad Gooch not to use that in his biography, but it’s exactly what he did use. Ha! When I went to the Wagner Writers’ Conference, it was to meet Frank O’Hara, not Kenneth, whose poems had lured me less, except for the lines about the “new poem” in Fresh Air. Anyway, I met Frank, and he wrote me a few letters whose yellow tone I still remember. These letters were extremely generous, the word one uses almost as a reflex with Frank. One of them said of course he liked my poems or he wouldn’t have gotten them to be published in The Floating Bear without my permission. He writes that because I had made them into little booklets (early pamphlets I put together: Poems, A Second Winter, When will the Bluebird, haha) he thought they might be available. He was apologizing for getting me published.

124

I met him in his little apartment. He was screaming at his mother very early. I was shocked. Remember that Diana Di Prima was disturbed by my calling Frank “Mr. O’Hara,” but I was fifteen and he was (1962) 35 or so. Four years till his death. We seemed to talk for hours. He lent me Pasternak’s Safe Conduct. He said Kenneth had thought the “Ode to James Dean” sentimental, did I? He asked me why there were so many seagulls in my poem. I told him I was living half my life on the Atlantic. He kept asking. I said they were probably symbols of liberty like his ending to “Ode to Michael Goldberg.” Because he teased me about it, I never mentioned a seagull again for fifty years. No, I think I simply stopped. He ended a letter “yours, in shaking seagulls.” By the way, I was influenced by Spicer’s work a little bit at this time.

125

Frank was a genius in the sense of bells going off in my head and Gertrude’s head. He was embarrassingly brilliant. Kenneth joked that he and Frank would have to kill me in what they called “The Staying on Top Game.” I was actually frightened. I played the Nigun of Bloch for Frank, and he made a call, I think to Joe LeSueur, asking him which violinist was on the radio. He was of course utterly sophisticated about music, and we talked forever about it. (That’s when the Virgil Thompson job was raised by him, I think.) Anyway, I contrasted this knowledge with Allen G., who when I played the Bloch asked me whether I had just made that up. I was an arrogant young violinist, and I told Allen it was called Nigun or Improvisation. I couldn’t believe Allen thought I had just invented it.

126

Anyway, years later I played the piece for Michael Palmer’s birthday ― or Ann Lauterbach’s ― and a Language poet filled with scorn turned to me and said: “Well, that was pretty Romantic, wasn’t it?” I thought: It was good enough for Stokowski and Frank O’Hara; it could meet up with another comment.

127

Well, Frank invited me to parties, and it was difficult for me, because I didn’t drink. Once he was angry for me with good rights, because I gossipingly said to Bill Berkson: “Tell Frank to write me more long letters, since you could be called the power behind the throne… ” At that point, Frank angrily said: “Watch out, David or you’ll become as gossipy as Gerard (Malanga).” I began to turn away and cry, and as I left the party, Ron Padgett called out: “It’s time for the straight men to leave!” I thought he meant as in comedy. Maybe he did. But I told Kenneth about it and he said: “Don’t worry, we were throwing lamps at each other later in the party, and Frank won’t remember.” I thought he would, but at a reading or other event, a week later or so, Frank saw me and said: “Oh, hi David, so great to see you” (or something like that). I was so relieved I began to ask him what he thought of Art and Literature. He said: “Belles lettres you know, dead.”

128

When I met him at MOMA, I was dazzled by his job at my favorite museum. (Yes, I am still nostalgic for the early smaller days without cafes on every floor.) A painter I most respect has told me it’s outrageous that I think the past was better. He might be right; it’s easy to be nostalgic, as Kenneth said. I have seen (he said) my own daughter aged 4 be nostalgic.

129

Anyway, I made some hilarious judgments, and at the time Frank teased me mercilessly about the Hide and Seek I still liked. “Why do you like it,” he asked? I knew I was in trouble and said: “I think I like the bright colors.” He mordantly ended my love affair with Tchelichev by sighing: “Oh, you should have seen it BEFORE the fire!” He mocked either Ferlinghetti or Prévert as the poor man’s version of the other. He told me, of course, it had taken him months, not a day, to write the long Goldberg Ode. He was pleased that I accepted the Ode. Anyway, he was the only older poet who thanked me for an invitation to Newark and promised to come. (He didn’t, but Ron and Ted did.)

130

Tell us of another embarrassing moment with Mr O’Hara, some kind of contretemps. Or was everything always “smooth,” as it were, with him?

David Shapiro with his wife

131

The most embarrassing moment with Frank was when he held my hand in front of my girlfriend of the time (1963!) and also when he left me alone for a few hours with Ginsberg, whose first question to me (after lugubriously looking through every book there, as I say in silence) was: “Are you a virgin?” And later Allen asked: “Why don’t you write about your beautiful green sweater?” I replied: “Because I don’t want to write about my beautiful green sweater.” He continued, and I mentioned Blake, and he dropped the beautiful green sweater.

132

Frank dazzled me, though I found his voice very human and nasal. He praised a poem, because I had called it “To Betsy Davidson” but started it with the phrase “Dear Elizabeth.” Kenneth said: “Frank is all heart, and I’m all art.” At his funeral, Frank Lima and I were furious that the priest had called him naughty like Bobby Burns.

133

I was influenced by almost all the Odes, but the supreme one on Pollock and the one for De Kooning remain standards of excellence, haha, for me. I only knew him for four years or so, but as Ron once said, “Those years seem to be stretched out in time longer than twenty years without him.” His parties were notoriously diverse. I was shocked when a few turned on LeRoi (now Amiri) for bringing jazz musicians to a party. I grew up partly on jazz. Kenneth saw it as a cliché. One day I met LeRoi at Frank’s, and there was a discussion of some black riots. “The right side finally got the guns,” said Frank, directly enough. I loved him for that, because I had grown up among socialists and hadn’t heard much politics in New York.

134

I heard Frank read at Columbia once, but was a little disappointed, except with a hilarious play about Ted and Ron, where every remark of Ted is a little brutally dumb, and every counter-statement by Ron is elliptical, brilliant, and enigmatic. A wonderful skit. But later Kenneth said to me, “Well, he is a revolutionary poet but without a revolution.” By the way, after Frank died, Kenneth, upon hearing me quote him said, “Never repeat that.” I told Brad Gooch not to use it, but it’s one of the two things he did use. I think it’s useful, anyway, pace Kenneth, because it shows his unbendable loyalty to Frank and also a good perception that a lot of Mayakovsky could have lodged itself inside Frank and did. (Larry Rivers’s Russian Revolution gigantic work was springing up.)

135

By the way, Kenneth was in love with the way Frank revised to get a few short “u” sounds in a Jane poem. Kenneth looked at Frank Lima and me crying at the funeral and said: “You guys would like to change the world.” We were so angry when Allen came up and said to me (I realize now very wisely and sweetly): “Don’t worry; you are not going to die.” And then he said: “Frank is alive somewhere.” I immediately thought that was a sentimental lie, but I am now touched that AG tried to console us.

136

I loved having Frank casually in an audience at The New School. I remember seeing “Biotherm” in Audit Magazine and loving the Dantesque ending. Recently I see that one of the Dean sequences is a straight homage to Mahler’s Rückert song, really one of Frank’s great poems about “being out of touch with the world.” No one seems to have noticed it’s a word for word mistranslation of the Mahler. Just rereading it recently gave me goose-bumps (goosy-goosy in Czech) because it was elegant, grand, surprising.

137

Bill Berkson told me once the adjectives Frank used for what was great art. When I was young, as they say, in 1962, everyone said: “He’s too bitchy to be a great artist.” Ciardi was writing me that Frank was not so sparkling at Harvard, as say his student Donald Hall. When I was told he was too bitchy for Arthur Cohen, I said: “No, Catullus is also bitchy, to name one.”

138

He was tough on Frank Lima’s problems in a tough love sense. I can’t wait till all his letters are printed. Barbara Guest told me that she loved to speak to him late at night, because they were both insomniacs. I understand that now he seems to be, as Richard Howard once said, the man who was always going to die young. But no one I know who knew him felt him suicidal. Unless all drinking is. Anyway, Kenneth told me that at the hospital, he was convivial and angry. He presumably said: “Hi guys, there’re drinks for everyone!” I made a vow never to see myself in a car ― a crazy irrelevant giving-in to my own rage and fears.

139

For me, the end of Frank’s life was the gigantic ending of what seemed like an entire community, the community before say Saint Mark’s. But I don’t really feel that the drawings, as it were, of him after death know him. He was not James Dean; he was a wild, formal, formless genius. He wasn’t some vapid second-rate Apollinaire. He was the real thing, like Lorca. I sometimes think he is exactly as good as Lorca, that is, endlessly good.

140

I don’t appreciate little truncated versions. All the Odes should be reprinted as a book. His love for Michael Goldberg is an example of him being democratic, flexible, and free. “And that’s the meaning of fertility/ hot and moist and moaning.” My own tones I hope are closer to that than to anything. When Johnny Myers rejected me at fifteen for a de Nagy pamphlet, Frank consoled me immediately: “Oh, David, don’t worry, Johnny doesn’t like anyone he hasn’t discovered.”

141

I am the proud owner of “Ode to Necrophilia,” drawn again and again, as Frank tested his poem. His handwriting alone was as gorgeous and original as Twombly. That was a gift from Michael Goldberg in the age in which art was still a gift.

142

So many memories!

143

It would really take me another 300 pages to talk about his tones, about the sudden question in “A Step Away from Them,” about his deletion of two lines that would have ended the Ode to Michael, about his plays, about his art criticism. His art criticism is always put down as merely purplish poet’s prose. Frank was in his 30s when he did book after book for MoMA and executed big shows, and after his death, many artists, Elaine de Kooning told me, refused to show without Frank being around. His inveterate good taste and wild ambition would have lit MoMA for years.

144

So if I had to sum up: Frank O’Hara, whose letters I still long for, was a poet of the stature of Lorca. His gigantic poems “Easter,” “Second Avenue,” and “Biotherm” are sometimes deleted by false selections. His letter to Johns about the poets he should read I found out about by accident. I told scholars to use it (the letter), but it still hasn’t been, and it shows his original taste ― he praises Wieners and Burroughs; he praises, or at least underlines, so many disappeared writers. His list is about fifty years ahead of anything.

145

But it’s hard not to mistrust those who see him as a writer of little Pop bits and “[Lana] Turner collapses”. His ambition was unwavering, and in fifteen to twenty years he wrote some of the most intense tones/ structures/ decompositions as anyone. A thousand poor imitations of him are written every afternoon, but this doesn’t mean we should hold it against him.

146

He was a love poet, and though Kenneth once told me that Frank’s masochistic loves took up too much of his time, he was more open than almost any poet of the century to his century, for which he smiled. Only he talked to the Sun, Kent, and only he desperately wanted to reach you, us, everyone, democratic, flexible, and free.

147