| Jacket 37 — Early 2009 | Jacket 37 Contents page | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/37/r-padgett-rb-cox.shtml

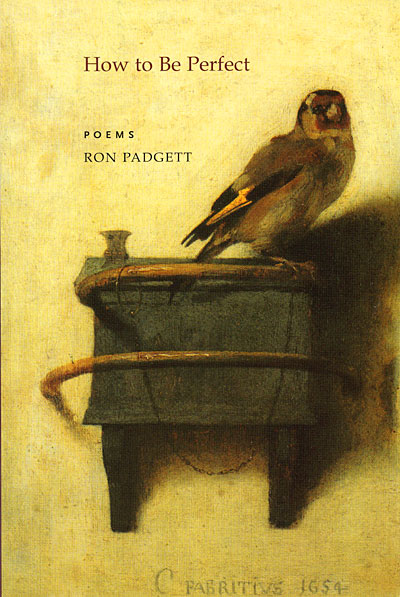

Ron Padgett

How to Be Perfect

reviewed by Jack Cox

114 pp. Coffee House Press. Paper. AUS $ 13.26. 1566892031 paper

This review is about 8 printed pages long.

It is copyright © Jack Cox and Jacket magazine 2009.

See our [»»] copyright notice.

1

Ron Padgett has written his recherche du temps perdu. Throughout this specular book he loses again what has been lost, waits for what has come and because most poetry saves nothing but time, is perfect timing. A basic rhythm, true to the moment of writing, appears to be one of holding and releasing. The poems are connected across gaps but the head comes away from the body more than once, and the attack of the collection — ‘Mortal Combat’ — sees the author trying to stop the idea of an English muffin from descending further than his salivary glands to his fingers, perhaps, where it is too late, and from ‘trying to pull me away from who I am. I am / a squinty old fool stooped over / his keyboard having an anxiety attack over an English muffin!’ Probably the unwelcome idea wants to pull him away to the fridge of another poem where Frosty ‘is stuck and so am I.’ So an end to the unstoppable flow of material is a block but iamb iamb is the purest and most brilliant, the complete identity of poet and poem in strife. It occurs once more at the end of another line. Later the author experiences a ‘fantasy block’ over a young girl in the gym but when you close the book, in the dark this poem secretly presses against another in which his old lover and he coo at each other in ‘the soft warmth of candlelight.’ These poems are communications from ‘between breaths’ as John Ashbery wrote once.[1] Stopping and starting on the way to nowhere, their paratactic metronome swings back and forth through life.

Paragraph 2

After the opening struggle, the first poems take place, or begin to, in childhood. Ostensibly they tell us what kind of a poet is growing up. Other kids had spinning tops but

3

My top slowed down and

went crazy-wobble, and I

got up and spun

and staggered dizzy,

flopped and threw

the spin into the floor.

4

‘Tops’ is a fourteen-line poem in which the first of the lines quoted above falls on the turn in an Italian sonnet. Like iamb iamb, the joke is typical of a poet who has been ‘young enough to kill myself for art’, and has probably lived for it. It shows up less as a poise he has maintained between idiosyncrasy and high technique as a marvelously helpless symbiosis of one and the other. Ron Padgett still likes not to look up in a reference book the Swiss Family Robinson whose name confused him when he was young. Elsewhere he has written about his childhood taste for repeating a word until it separated from its meaning and started to sound like anything else.[2] Here in ‘Rialto’ he remembers the theatre of that name in his hometown. Only later, he writes, would he learn about the bridge, and how things can ‘start all over / as a perfectly clean phoneme in the heads // of the innocent and the open’. (There was a Rialto theatre in Sydney that disappeared in the thirties, in time to start over in Tulsa.) You are made to think of ‘Rinso’ a few pages back, a soap ad dream vision of his own infancy perhaps, a new birth that makes things ‘sparkling’.

5

Ron Padgett keeps his language clean. Thinking up truisms makes him ‘feel contaminated’. When heavy combinations of words are too often handled as single units of meaning, they collapse on you ‘like a ton of bricks’. Polishing a sentence back to its smallest parts becomes an act of innocence in the etymological sense — you make a ‘blizzard cube’ in a children’s book where it ‘won’t hurt’. Likewise you listen for the echolalia in ‘Echo Lake’ and are not a dupe for definitions because the past gives back all kinds of possibilities. Telephones once offered something like the phonemic drift of the Rialto in small scale:

6

It was an act of kindness

on the part of the person who placed both numbers and letters

on the dial of the phone so we could call WAverly,

ATwater, CAnereggio, BLenheim, and MAdison,

DUnbar, and OCean, little worlds in themselves

we drift into as we dial

7

The little worlds of these poems (which some drift into when they die) are not the world, they are places for themselves, and the person speaking is not recovering his childhood in order to locate it in a place before his writing but to provide the writing with the imminent quality that lies in its methodological inheritance. When he writes, ‘I was waiting to happen’ it is not the same as the figure of the writer waiting to ‘find his voice’, a blind conceit he has written a nice little poem about elsewhere which ends:

8

I hope I never find mine. I

wish

to remain a phony the rest of my

life.[3]

9

Instead, the level of play intrinsic to all reading and writing is recovered along with a cleanness of sign and sound from a kind of back-to-basics memory of childhood. Perhaps the phoneme hidden in ‘phony’ is the secret content of that wish, an hiatus to meaning that has a graphic counterpart in those candles sticking up on their stanzaic cake. I I I (take a breath) wish… In this kind of family history anything is possible. ‘Roy wasn’t really my uncle’, he writes. It does not matter, he could be yoR uncle. Spin it how you like.

Ron Padgett, New York City, photo John Tranter

10

So much for forefathers. The author says he plans to finish reading the Commedia but when he wants to talk about Dante his involuntary memory interrupts, once with the comedian Shecky Greene, another time with Jimmy Durante. But he does remember Dante and his canonical followers when he is not talking about him. A poem about Geoffrey Chaucer tells us that everyone in his day moved in stop action, ‘so they could be shot into a tapestry.’ In the flame-bordered poem that follows, called ‘The Question Bus’, the shutter is a shuttle again when the speaker considers where someone’s friend is going to fall: ‘Somewhere in between a rock and a click, where the abstractions / roam about in their ghostly attire. They are haunting our / thoughts, we who wear human attire.’ The collection mimics the trains of unconscious memory, and here in the last words is a darkly burning memory of the Inferno slipped in as easy as Jimmy Durante (that happens to come from the first bit of it I ever read and that too was in someone else’s poem, whence it went through me in a fork of lightning to linger like an unanswered question until a year or so later I read what I recognised to be the original and learned about the ghost of great art. Hello, old friend, so this is where you’ve landed lately).

11

Sometimes it is his own work that is cycling back; he even repeats an old piece of advice (‘wash the dishes’). Saint Augustine wrote that memory is ‘the belly of the mind’.[4] Once Ron Padgett wrote: ‘there is indeed money in the tummy’[5]; now someone has spent his ‘fifteen units of beauty’ too fast and may be on his way back to the bank when he runs into Augustine. Sometimes it is someone else. Who is in the wind ‘coming up the lane and into the window / to enlarge you to sky size not / for the sake of your so-called immortality / but so you can growl even louder / in the sleep that has become both yours and ours’ if not Frank O’Hara, who could have said the part about ‘so-called immortality’ and who once appeared in a poem Ron Padgett wrote in which his eye was the window in a building that was O’Hara (window comes from the Old Norse for wind-eye). He also wrote: ‘The wind that went through the head left it plural’.[6]

12

Enough; the poems are multitudinously haunted. It is a theme in the book — sometimes apparent in a repeated complaint about the dead artists who are not there when you are with them, who do not see you, which is actually cured by the scary appearance of William Shakespeare himself: ‘His dark eyes penetrate your head. You look down. His shoes / make you feel like screaming.’ But the theme is in a fugue, and the person who is most often missing, about whom the whole memory book turns, is the author’s mother. Before you know that she has died he tells about being on the phone to her and not wanting to move back to Tulsa, ‘so she / could see me every day and not / just hear me’. Now her passing diffuses through the endless calendar of poems a current of silent air and invisible mist. Others to whom he owes a debt have died and are remembered by this poet who thinks about death but would prefer not to. His reflections on it are in fact always doubled in some way. By the end of ‘The Alpinist’ he has climbed to this height:

13

From up here

I can see both my head

and my body and the river between

and when the

river stops flowing

I will find myself next to a hut in the Alps

with cows

and flowers but without words

But that’s for later.

14

Like with the Pearl poet, who repeats end words but lets them slide between different meanings, we find at the end of the last poem — a complaint against absence called ‘Bastille Day’ — the lines:

15

The

red and grey sky

above the rooftops

is darkening and the

inhabitants

are hastening home for dinner.

I hope to see you

later.

16

(The book is an afterlife for his mother but is dedicated to his grandson and his grandson’s parents.) The poems swing between two worlds for which they have no words. Flowers on a grave spell ‘Mum’. Sometimes instead of ghosts there are animals or things who also “escape” the poems and in doing so leave something ‘hidden’ in them, a ‘secret’ without a voice. A nail, for example, ‘buried in the wood, / with no lips / to tell the tale’, of whom you are reminded later by the stapler left behind by his mother, now ‘floating’ in a poem preceded by the lines, ‘Would you tell me / your secret then?’ As incommunicado as Frosty the Snowman is a squid, a secret author who ‘hastens to flee your liquid writing’. The squid poem is really wonderful. It seems to have been touched by Marianne Moore (as have a couple of other places in the volume) not only in the bookish animal who escapes the writing as the writing runs into it (you follow two colons into the insides of the squid but end up outside) but in the idea that the squid is an impossibility itself, since what you will ‘never have’ from it are its own ‘dark and human tales’.

17

The poem is called ‘Different Kinds of Ink’, and as there are two kinds of ‘ink’, one hidden, in the title, so the squid has a companion in the ‘train’ of an earlier poem, hidden in the darkness of the letters that make it. ‘One train may hide another / or it might hide the mountain / into which it disappears / and hides itself’. We are warned: ‘This is not a metaphor.’ No, ‘It’s a stanza, in which / the train is hiding.’ It is ‘A Train for Kenneth’ and is followed by an elegy called ‘In Memoriam K.’, where one K hides another along its dark lines and the ‘hidden’ birds who sing for the living hit notes that seem to be

18

inside my head which is

come to think of it where

I hear

them, as I hear him,

he who made me so much

who I am and now must be

alone

with him now he is gone.

19

So it is that the surface of the poem is full of hidden trains and visible trains, a ‘face’ he lets ‘carry all kinds of packages / back and forth from my brain to the world’, and where you can be alone with all the things that are not there, being there but not elsewhere. Which is why it is so awful! ‘The emptiness of the room was worse / Than the emptiness of the universe’.

20

The problem element is time. Ron Padgett walks into his poems from the world but their stanzas can move in double time and leave him ‘here, / which is where I think I am, or was, or there’, or simply ‘leave / you far behind.’ But that they do not do of course, not yet, and when they do it is your own feet that will have been there since the beginning — finally he writes an ‘Elegy of No One’:

21

Time passes slowly when

you’re lost in paradise,

then gradually slows down to a

disappearance

but only for a moment, as if inside a footstep

that

pauses on the stair to wait for its shadow

to catch up, for it had not

yet vanished as

the other had, and you have the idea you

wanted to

have had when

the candlelight took away the distance,

leaving only a

residue of dimness and fading

falling to one side and off. Time goes past or

you

go past time, the outcome is the same if you think

of it that way,

but if you don’t think at all

the footstep will have existed on the

stair

without you, as it always has, and perfectly so.

22

It is distance that disappears, a spot of ink blocking the vanishing point of the present, a perfect save in the run of lost time. Once you have that sorted where does it leave you? It leaves this poet looking out on the appalling world and not quite asking what it can do for poetry, and complaining about how hopeless it can make him feel knowing that his poetry can do nothing for it. For instance, being so careful with cultural and linguistic currency, he worries about his being accessory to a bad economic system. One problem is, as he demonstrates, that his sallies into public discourse come out bad (it is after the Durante-Dante episode that he makes his only effort at civic polemic, the ‘truism’ that makes him ‘feel contaminated’). But the situation is basically summed up in an early poem called ‘Toothbrush’:

23

If I could save the world

by being

crucified

I certainly would.

But who would nail

a toothbrush to a

cross?

24

Sometimes, as in ‘The Absolutely Huge and Incredible Injustice of the World’, the poems can hit perfect pitch on this, but it is not always successful. ‘Straighten up your room / before you save the world’ is good advice to a poet, not to mention to someone just in a room, but there is something off about the hokey but, on its own, honest qualifier: ‘Then save the world.’ Is it because it is the one bit of useless advice in a poem otherwise full of useful advice? Likewise, when he equivocates in the toothbrush poem between being ‘insufficiently angry’ and ‘too angry’, it feels like an uncharacteristic moment of bad faith. Though all over this aspect was also one of the nicest new turns in the book, and is mostly funny, beautiful and wise.

25

When you chase the tricks what can sometimes escape is the grace of the artist. That can be helped but no longer by me. One reason this review is inadequate is that its subject is a masterpiece and masterpieces give you a hell of a time.

Ashbery, John. Collected Poems 1956-1987. New York: Library of America, 2008.

Augustine. The Confessions. In Basic Writings of Saint Augustine. Ed. and trans. W. J. Oates. Vol. 1. New York: Random House, 1958.

Padgett, Ron. New and Selected Poems. Boston: David R. Godine, 1995.

———. Great Balls of Fire. Minneapolis: Coffee House Press, 1990.

———. Blood Work: Selected Prose. Flint, Michigan: Bamberger Books, 1993.

[1] Ashbery, ‘And Ut Pictura Poesis Is Her Name’, Collected Poems 1956-1987 (New York: Library of America, 2008), 27, 520.

[2] See Ron Padgett, ‘Foreign Language’, Blood Work: Selected Prose (Flint, Michigan: Bamberger Books, 1993), 4.

[3] Padgett, ‘Voice’, New and Selected Poems (Boston: David R. Godine, 1995), 20-21, 85.

[4] Augustine, The Confessions, in Basic Writings of Saint Augustine, ed. and trans. W. J. Oates, Vol. 1 (New York: Random House, 1958), Book X, Chapter XIV, 157.

[5] Padgett, ‘Tone Arm’, Great Balls of Fire (Minneapolis: Coffee House Press, 1990), 181, 69.

[6] Padgett, ‘Reading Reverdy’, Great Balls, 1-2, 87.

Jack Cox

Jack Cox finished a Bachelor of Arts at the University of Sydney in 2008. He lives in Sydney.