| Jacket 38 — Late 2009 | Jacket 38 Contents page | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 10 printed pages long.

It is copyright © Dale Smith and Kenneth Goldsmith and Jacket magazine 2009. See our [»»] Copyright notice.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/38/iv-smith-goldsmith.shtml

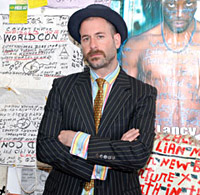

Kenneth Goldsmith is the author of ten books of poetry and the founding editor of UbuWeb. An hour-long documentary on his work, “Sucking on Words” premiered at the British Library in 2007. He teaches writing at The University of Pennsylvania, where he is a senior editor of PennSound. A book of critical essays, Uncreative Writing, is forthcoming from Columbia University Press. Photo of Kenneth Goldsmith by David Velasco.

Dale Smith (born 1967) is an American poet, editor, and critic. Smith was born and raised in Texas and studied poetry at New College of California in San Francisco. He now lives in Austin, Texas with his wife, the poet Hoa Nguyen, and is working on a PhD at the University of Texas. After moving to Austin in 1998, he and Hoa Nguyen started the small press publishing venture Skanky Possum. Smith’s poetry and essays have been widely published, including an appearance in The Best American Poetry 2002.

JACKET INTERVIEW

If any Jacket readers would like to take issue with the main cultural and historical currents in this discussion, please let me know. No ad hominem comments, please.

Email to: John Tranter, editor.

Section 1

Kenneth Goldsmith: I’m interested in engaging in a dialogue with you in spite of — or because of — the fact that we see things very differently. Too often, I’m in discourse with people who feel the exact same way I do.

2

Dale Smith: Kenny, thank you for inviting me to share these words with you. It’s important that we see things differently, but also that we look for points of intersection and shared vitalities.

3

KG: To start, I approach poetry with everything I learned in the art world where I had my training. When I moved into the poetry world in the mid-90s — in comparison to the art world — the work seemed shockingly passé: either disjunctively modernist or else depressingly academic and blandly subjective, full of “special moments.” Both ways of writing seemed pointless to me at the dawn of the internet age.

4

DS: I admire that you bring the perspective of the art world to poetry. The study of rhetoric has helped me tremendously in how I read and write poetry, and how I look at it as potential public documents that influence our belief and desire or, conversely, challenge us to expand our capacities as thinkers, writers, and just ordinary people. I really like some of the ideas behind Conceptual Poetry. Maybe you could talk a little about how your art school experience influenced your poetry, and perhaps say something about why you chose poetry — or language — as the medium for your art?

5

KG: What I learned in the art world is that anything goes. The further you can push something, the more it is rewarded: to shoot for anything less in the art world is career suicide. The art that is deemed the most valuable is rarely the most finely-crafted, the most expressive, or the most “honest” works, but rather those which either attempt to do something that’s never been done before or those that synthesize older ideas into something new. Risk is rewarded. Those who follow tradition in a known, dogged, and obligatory manner are ignored. Unlike the poetry world, the mainstream of the art world since the dawn of modernism has been the avant-garde, the innovative, the experimental. The most cutting-edge work — the work with the biggest audience and historical import — has been the most challenging. One only needs to think of the biggest names of twentieth century art to confirm this: Duchamp, Pollack, Warhol, Koons, etc. all made outrageous propositions that became the mainstream history. I find this inspiring.

6

These terms that I use quite often to situate my practice— “impact,” “audience,” career,” “radically important,” “historical,” “experimental,” “cutting-edge"—might have different meanings for you.

7

DS: The narrative we both want to tell relies on very different assumptions about poetry, art, modernism, and the avant-garde. And those differences interest me tremendously. I treat poetry as something composed of specific worlds, communities, environments, publics. I’m interested in what poetry reveals to us of the worlds we live in, and insofar as poetry can provide witness to those worlds, I am compelled by its potential for social change.

8

But I think that we have different notions of an avant-garde, for instance. While you value formal evolution — the “new”—I associate an avant-garde with social change, though I have a wide and diverse sense of what “change” here can mean. This dialectic of an aesthetic avant-garde in conflict with a historical avant-garde interests me as a poet and as a rhetorical scholar. I’m not sure we have to condemn one or the other, but perhaps by evaluating them with some purpose in mind we can expand our knowledge of how new work enters the world for specific people.

9

My own experience as a reader relies on diverse trails, following voices, building trust, looking for peculiarities of experience and oppositional points-of-view. I am compelled by what is buried in the historical record, or by what has been eroded in the cultural forces of oppression. As a writer I look for points of intersection, too, between intimacies of feeling and the shape of public thought. The aesthetic or formal experience of this is secondary. New is news, but not necessarily “new” in the way you said it a moment ago. But my enthusiasm for poetry could be blinding me to what you mean, and I welcome your perspective at this point in the conversation.

10

KG: Well, regarding public intersection, there’s different ways to look at it. In my group of peers, the only poet I know who has connected with the general public is Christian Bök, whose wildly experimental book Eunoia is the bestselling book of poetry in Canadian history. In fact, when the British edition of the book was released last year around Christmas, it hit the UK top ten list, just under Barack Obama! Most of Christian’s readers are not poets at all; they’re just folks who are stunned by the achievement of his book. Christian is a populist and an avant-gardist; someone who shows us that these two don’t necessarily need to be oppositional.

11

I’m going to take it a step further. A common accusation hurled at the avant-garde is that it is elitist and out of touch, toiling away in its ivory tower, appealing to the few who are in-the-know. And I’d agree that a lot of “difficult” work has been made under the mantle of populism only to be rejected by their intended audience as indecipherable, or worse, irrelevant. But conceptual writing is truly populist. Because this writing makes its intentions clear from the outset, telling you exactly what it is before you read it, there’s no way you can’t understand it. My books make a case for this: who, for example, cannot understand a book that is a transcription of every word broadcast during a complete baseball game? Or a day’s newspaper that has been transcribed word for word? Or a record of what one man said over the course of a week? It’s very simple. Anyone can understand these books. But then the real question emerges: Why? And with that, we move into conceptual territory that turns away from the object and toward the realm of speculation. At that point, we could easily throw the book away and carry on with a discussion, a move conceptual writing applauds. The book as a platform to leap off into thought. And this, then, is the real social space of conceptual writing: the conversation.

12

DS: Yes, I agree: conceptual poetry can be seen as a populist form: there’s no mistaking what’s taking place. But this is where I think you’re either misleading your readers, yourself, or me in terms of the experience of the text. In many ways, your writing associates closely with ideas that have been discussed around this thing I’ve been calling Slow Poetry. By taking traffic, or weather reports, or a Yankees-Red Sox game, and transcribing those texts laboriously, and carefully arranging them, you submit books that bring aspects of the world into new perspective. If Language Poetry took language as its primary concern, you go out of your way to shape language with new conditions of context: and I find that absolutely appealing. Instead of calling it Conceptual Poetry, perhaps you should have named it Contextual Poetry, though, perhaps, it’s not as sexy. The “concepts,” then, don’t appeal to me as much as the strategies of writing you employ: transcriptions of radio broadcasts, tape-recorded body sounds, printed media, etc., and the resulting delivery.

13

In a way — and this contextualizes your practice more within a realm of poetics than of art — but what you have accomplished in Weather, Traffic, and Sports in some ways picks up on certain aspects of writers like Philip Whalen or Joanne Kyger. Like them, close inspection of particular environments is at stake in what you do; only you rely often on mediated sources. Whalen and Kyger receive visual imagery, too, and investigate the relation of phenomena to mind within particular environments. They, too, are motivated by relations of time and space to the arrival of words that document these moments. By stripping that down to mediated sources, you are able to limit the self-intrusions that inevitably occur while arranging a text. And I see, too, a loose affinity in your writing with the Black Mountain projectivist concerns, though you certainly, again, attempt to restrict the projection — or to manage it through other voices. But Black Mountain grew out of a conversation between two people — two men. Your conversation is with historic trends or avant-garde movements in art — the social reception and extension of relevant practices. And so I’m led to wonder about the nature of the conversations generated by Conceptual Poetry — what they lead to. Why throw away the text — the artifice of your motives and of the reader’s experience?

14

KG: The conversations are much more interesting than what’s between the covers of the book. These books are impossible to read. I hate reading them myself. But they’re great to talk about!

15

DS: Okay, but the situations and experiences of life your books recontextualize are much more interesting to me than the generation of opinions and ideas around them. Opinion can’t stand up to the raw achievement of containment and delivery in Traffic, say: the revelation of your books is that language requires perspective — its materiality is meaningless without an approach to it. So the real social space may indeed be the “conversation,” but the poem/books you create contain more than the social, ya know, and make compelling documents?

16

But let’s continue talking about the conversation, rather than the work, if you’d prefer. By bringing Conceptual Poetry to the Whitney earlier this year, don’t you feel as though you betrayed the radical impulse behind the avant-garde? Or perhaps I’ve fallen for the performative gesture, and in my dismay over the carrying over of Conceptual Poetry to the Art World Institution I’ve simply fallen for a scheme to generate discussion around Conceptual Poetry?

17

KG: Honestly, Dale, if the Whitney wanted to do a night of Slow Poetry, would you really say no?

18

DS: In the context of Slow Poetry, I would have to refuse, though I would lose sleep over it. Or, perhaps, I’d pull a Marlon Brando, and send someone else to collect the trophy — use the opportunity — put it toward some other purpose. I might ask for the money to document some other kind of event — in a nursing home or something. It would be difficult, and I realize the pressure involved, but that’s how it is.

19

KG: Wow! That’s amazing. Tell me more! Why would you refuse? I’m fascinated!

20

DS: It has to do with Slow Poetry. It doesn’t belong to me. And there’s nothing to promote. And I don’t want to be responsible for institutionalizing anything in that sense — slipping under the Museum’s covers. I would rather send Jack Collom or Sotère Torregian or Joanne Kyger. Or a homeless person dressed up as me saying whatever they wanted to say — that would be an interesting conceptual gesture, I would think.

21

Not too long ago, on Silliman’s blog, Kent Johnson left a comment which proposed that “The poetic politics of [Flarf and Conceptual Poetry] begin where those of Language poetry ended.” It’s a pithy formulation and an interesting notion, perhaps, to be explored. I wonder, actually, if by this he partly means that in fact the new poetry-“avant-garde” is very much, and quite willingly, inside a “Building” that’s quite primed and ready to receive “Art Works” of the kind you are offering. The installations proffered want to be provocative, and no doubt some in the “populist” audience, as you have it above, will see them as so; but the installations are inside a kind of museum, really, ready-made for them, if you’ll pardon the pun. Don’t you think? And the museum is certainly not free of history.

22

KG: The institution, if willing to support and not censor, can only benefit adventurous poetry. The more people who know about this the better. This divergence reminds me of the scene in the film Food Inc. when Stonyfield Farm CEO Gary Hirshberg storms Wal-Mart from the inside. These institutions are not going away any time soon. Listen, I very much believe in the power of innovative writing — and the thinking that comes with its practice — to affect people and to change lives. It’s certainly changed mine. In fact, I really want to fight for its visibility in this culture which is one of many reasons I feel compelled to take it to a bigger stage.

23

Yet I can’t deny my ambition. And in this way, I’m reminded of John Cage, a model for me, who struggled with the tug between worldly success and loftier ambitions, and it’s something I don’t think he ever was able to resolve. But what artist can? It’s hard to imagine an artist without ambition! Cage had more ambition that just about anyone — and showmanship and hyperbole to go with it — for which I’m grateful. Otherwise, if he wasn’t such a public figure, I very well might never have come across him. Cage used every available method — global and local, institutional and grassroots — to get his message out. I see no problem with that.

24

I’m reminded of you in other ways when I think of Cage, particularly in your Big Bridge statement where you refer to the MEND disruption. For Cage, music was a place to practice a utopian politics. If an orchestra — a social unit which he felt to be as regulated and controlled as the military — could each be given individual freedom not to be a unit. By undermining the structure of the orchestra — the most established and codified institutions in western culture — he felt that in theory, the whole of western culture could work within a system of “cheerful anarchy.” Cage said, “The reason we know we could have nonviolent social change is because we have nonviolent art change.” Does Cage figure prominently in your practice and thinking?

25

DS: Cage is remembered for his serious commitments to the environments we inhabit through sound, mind, body, eyes — and the processes of perception and thought that correlate these many elements or modalities of experience. With his ambition came also a seriously playful drive to help connect different audiences to his beautifully diverse perspectives on art. It’s no wonder he spent time at Black Mountain with Cunningham, Rauschenberg, and so many others who left there with this communal sense of art as a conceptual tool that helps other see their world more completely.

26

Cage was a genius who connected Black Mountain to music, art, and poetry in exciting ways. His ambition was at the service of the world: he seems like someone who wanted to explore his materials within limitations of time and space. I admire his ambition and respect his decisions to bring work forward.

27

KG: Talk to me about your own sense of ambition.

28

DS: My own ambition has always been, like yours, to put people in touch with one another and with artists who help us better understand the world we live in. My stubborn ambition has complicated my expanding sense of poetry’s possibility, though I want to see it engage more completely with diverse readers and auditors. Poetry’s the world I move in, though I am trying to look more and more at its communicative potential. I want to narrow the distance between things, between ideas and the world — to bring into contact previously alien notions or exchanges. That literary ambition, and that excess can be seen on my blog or in my essays or reviews. I’ve gone out of my way also to publish poets within my own limited social and practical capacities. (Hoa Nguyen and I published ten issues of Skanky Possum, along with several books and chapbooks, and I’m now working with Scott Pierce of Effing Press to publish more.) And like you, I’d like to see poetry participate in scenes that expand far beyond strictly literary sites.

29

KG: One thing I learned from Cage is to accept everything — even those things which we find distasteful. Cage proposed that if all sounds are music, if we take our likes and dislikes out of the picture, we can objectify even the most disturbing sounds, thereby turning them into music. Cage’s thinking, of course, was Zen-based and he often told a Zen story that justified the existence of evil in the world by saying that it was there to “thicken the plot.” Cage also wrote a piece called “How To Improve the World: you will only make matters worse.” Likewise, a hero of Cage’s, Buckminster Fuller, said that if it can exist on this planet, it is natural. Take pollution, for example: the problem is not its toxicity, it’s that we’re not smart enough or creative enough to figure out what to do with it.

30

It’s this sort of thinking that has led me to make statements like:

31

In their self-reflexive use of appropriated language, conceptual writers embrace the inherent and inherited politics of the borrowed words: far be it from conceptual writers to morally or politically dictate words that aren’t theirs. The choice or machine that makes the poem sets the political agenda in motion, which is often times morally or politically reprehensible to the author (in retyping the every word of a day’s copy of the New York Times, am I to exclude an unsavory editorial?).

32

I really have trouble with poethics. In fact, I think one of the most beautiful, free and expansive ideas about art is that it — unlike just about everything else in our culture — doesn’t have to partake in an ethical discourse. As a matter of fact, if it wants to, it can take an unethical stance and test what it means to be that without having to endure the consequences of real world investigations. I find this to be enormously powerful and liberating and worth fighting for. Where else can this exist in our culture?

33

DS: This reminds me of something Robert Duncan said in correspondence with Denise Levertov over the Vietnam War. They both opposed that war, but Levertov was an activist and tried to write poetry that would support her activism. She wanted change. Improvement. Etc. Duncan argued instead that such a use of poetry-as-activism became merely a kind of propaganda that participated within a discourse of power. In response to her being a poethics pusher, he famously stated: “The poet’s role is not to oppose evil, but to imagine it.” So, yeah, anything goes, in that sense. I’m right there with you.

34

To me the goal is also to subvert any social obligation associated with art in order to open new patterns of perception. I’m concerned with history — with the dead — and art’s obligations to what Walter Benjamin sees as a kind of historical train wreck. These last few days, as our conversation progresses, I’ve been imagining a Conceptual Poetics that might include those wrecked and stranded images — the perspectives of the dead. What do you think that might look like?

35

KG: I’m not really sure which train wreck or histories you are referring to. Could you please be more specific?

36

DS: I was just thinking of this notion of ethics and the “unethical stance,” wondering if one might address obligations to the past instead, assuming that we’re not inventing our practice alone. This will actually get us back to art history, because I was thinking specifically of Walter Benjamin’s “Theses on History,” and the image of Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus, which Benjamin responds to in his central claim, which is this: instead of history being a linear progression, it’s a heap of images and events — a catastrophic heap. The dead are present with the living, in a real sense. That is, the failures of the past — failed ideas and inspirations — reside along with the successes. (It’s kind of a conceptual leap he’s making, but I’ve always found it extremely provocative.)

37

This sense of the past is one of the things that maybe separate Slow Poetry from Conceptual Poetry. I’m concerned with the past — the histories mentioned at the outset of this conversation — and wonder how, specifically, the past resides in your own thinking about poetry — or not?

38

KG: Any notion of history has been leveled by the internet. Now, it’s all fodder for the remix and recreation of works of art: free-floating toolboxes and strategies unmoored from context or historicity. Darren Wershler has cited the unconscious migration of avant-garde strategies into mainstream memes as one of the great triumphs of the avant-garde: talk about populism! For instance there is a YouTube user “buffalax” who does homophonically subtitled translations of foreign language ephemeral videos that have spread far and wide as memes. One piece taken from a 70s German musical revue reads like a Bruce Andrews poem: “money’s eye muddish by design / nectar up the business I lie.” Most likely buffalax wasn’t inspired by Melnick’s “Men in Aida” or bpNichol’s translations of Apollinaire. So what was a serious avant-garde strategy, even one with political implications, has become a humorous meme. Innovative poetry, as Wershler says, has left the building and has migrated into mainstream culture.

39

All types of proposed linear historical trajectories have been scrambled and discredited by the tidal wave of digitality, which has crept up on us and so completely saturated our culture that we, although deeply immersed in it, have no idea what hit us. In the face of the digital, postmodernism is the quaint last gasp of modernism; and Bourriaud’s ridiculous notion of Altermodern ignores the digital completely, swapping it for a muddy globalism and materialism that acts as if technology doesn’t exist. Truly, the digital age is the great fact of our lifetime.

40

DS: You say: “Any notion of history has been leveled by the internet.” Kenny, that’s a provocative claim: could you say more about technology’s effect on history?

41

KG: Sure. I mean this in a positive way. An archive like UbuWeb throws together all sorts of figures that never have been in the same room together. It’s like a massive cocktail party where the Futurist F.T. Marinetti is over in that corner conversing with the feminist video artist Martha Rosler; or where poet Juliana Spahr is on the couch, deep in conversation with photographer Cindy Sherman; or where William S. Burroughs and the young video artist Cory Arcangel are doing shots in the kitchen. It’s a space that reimagines, collapses, and levels long-separated histories, opening them up, freeing them from moored narratives. History is one glorious big undifferentiated heap on Ubu. And what happens is that our users generally don’t know — or care — about those former histories. So you get these great inversions where people think of Jean Dubuffet as composer of musique concrete, Dan Graham as a poet, Julian Schnabel as a country music singer (really!), Martin Kippenberger as a punk rocker, John Lennon as a filmmaker, and Joseph Beuys as a dude who fronts a new wave band! And for many of Ubu’s users, all of this is just fodder for remixing. We find that looped samples Henri Chopin sound poems downloaded from UbuWeb are thrown into hit European dance mixes. So much for history and context. This isn’t only happening on UbuWeb but all over the web. Histories and their artifacts are certainly being reconfigured. How liberating!

42

DS: I see where you’re going with my comments about Benjamin’s wrecked heap: we’re surrounded by the past in the form of digitized archives. I understand that. But Benjamin’s notion of history is rooted in a sense of the catastrophic failures of history in the twentieth century, too. Paradise is the dream — a true liberating force (an impossibility?)—that is rooted in a meaningful search of images. We are surrounded by artifacts, endless fodder for remixing, as you say. But how do we proceed with this material in respect to the catastrophe? Are we really free to ignore the contexts and situations that produced these images? It’s not a celebration of the artifact in any sense that Benjamin speaks of, but a kind of seizure by them instead.

43

Technology, from the advent of writing systems, to printing methods, and now digital communication, provides ways of arranging and delivering texts and images to readers, viewers, and “users.” The only difference between a digital archive and a library is found in the different storage capacities and the greater accessibility offered by digital formats. A “truly digital immersion” doesn’t seem to answer anything more or less than print immersions — or the speeded up way of life after airplanes and cars or whatever. The human psyche remains at best a kind of Paleolithic thing, and there’s a lot of brain research and evolutionary biology etc that talks about this. The pace of life and our expectations in regards to information and communication changes as the technology continues to innovate. There’s more to deal with, but not enough silence and stillness (speaking of Cage earlier) to hear through things.

44

KG: I agree with you: technology is not a panacea for anything; stupidity continues unabated. But I’m extraordinarily interested in fact that this onslaught of technology is drastically altering the way we write and the way we think. The very nature and materials of what we work with — language — is completely different than it was even a decade ago. Each technology, as McLuhan pointed out long ago, brings with it a set of changes all around — and not always for good. We can’t look to technology for answers. But we must pay attention to it — and particularly the technological revolution we’re in the midst of right now — there are huge questions looming, but specifically, I’m interested in how these questions impact our field.

45

DS: The way I see it is this: we use symbols and can’t escape that fact. Symbols in words, images, acts, performances, etc. But the contexts for successful uses of symbols change. The “free-floating toolboxes and strategies” you speak of are not so “free-floating”: they are recontextualized for new purposes. But I agree with McLuhan’s sense of things, too: we are affected at some kinetic level by the technology we interact with, though I’m not convinced that the changes we experience, particularly in writing, are as drastic as you suggest. But I know I’m more impatient than I used to be if I have to wait on a slow connection or something.

46

As a poet I’m invested in the history of poetics, its long lore, and its entanglements with philosophy, rhetoric, politics, and other modes of thought and conversation. For me, how we relate to history — our various understandings of it — is essential. If we celebrate it as being leveled by contemporary technology, there’s a risk of solipsism, cultural isolation, and a misunderstanding of history as a gathering of products rather than as an ongoing narrative (in fragmented and disorienting form). We risk an irreverent attitude toward the past of other people, too, and the resulting consequences. Rwanda might look a lot different today without the European mineral and gem trade’s invasion there.

47

More importantly, we risk violating an imagination of the past that is really an ongoing narrative supported by artists and poets, among many others, if technology and institutions are seen taking precedence over other human networks and practices of art. I’m thinking for instance of Lorenzo Thomas’ poem “The Bathers.” It refers to the May 3, 1963, Life Magazine photographs taken in Birmingham, Alabama, by Charles Moore. In it white firemen release water from a fire hose on four young African Americans. Lorenzo’s poem reclaims the event as an image of black identity. He uses the occasion to integrate an African history and mythos into the violent experience of desegregation in the U. S. South. He questions the public expression of Charles Moore’s images and reorients them for his ironically titled poem. Andy Warhol’s duplication of the same Moore’s photo makes a very different critique and for a quite different audience based on very different historical knowledge and assumptions of public space. And this is why history is more than artifacts: it is the sense and measure we bring to those images, too.

48

In this way the past’s claims on our uses of its material are inescapable. We can, of course, ignore it, or we can try to understand it, and work with it. For example, it’s obvious that Ford or Chrysler or any other big, top-of-the-food-chain corporation employ surrealist strategies to make television commercials. This suggests that surrealist strategies turned out to be quite successful in terms of communication. But Surrealism had other goals in mind than selling cars. Just because Chevy can make a “humorous meme” from 1930s art experimentation only suggests that popular culture’s appetite for entertainment has advanced (slowly). But that’s a sociological issue; it doesn’t necessarily have anything to do with art or poetry. Once mainstream culture absorbs the moves of art — make new art that makes them uncomfortable. Or, rather, make art that matters within the situations you find yourself in. That’s the premise behind Slow Poetry. Where are we? What are we doing here? Who are we speaking to?

49

KG: I adore the machinations of the usurping of avant-garde strategies, because Chevy’s actions become the self-reflexive fodder and subject matter of Pop Art; which then is taken up by Baudrillard; which is then studied by students of semiotics, who then bring it back into advertising; which then is appropriated by Jeff Koons; which then is digitized and detourned by Paper Rad or Ryan Trecartin; which is then memed all over the world in parodic YouTube videos. Now, how can you locate, stabilize, authenticate that history? It’s a decentered, free-floating mess of signifiers and referents that would have delighted Breton or Dalí!

50

DS: Dalí, yes: I really doubt Breton would be clapping. What you describe sounds a little like a cultural ping-pong match. But I appreciate, you know, the back-n-forth of cultural references, the “self-reflexive fodder” and re-orientations spun from some Ur-strategy invented on the curb near the gutter of the Cabaret Voltaire in 1916. And at a certain point, as an artist, you have to make a decision. You can participate in the subject matter of pop art, and the institutional structures that support it, and you can do this without the need to authenticate history, and yet still feel obliged to honor it or something. You might also look to the lore and the speech of a people instead, or go to the records and images that remain as testament to some gone world or forgotten perspective that is not at all concerned with the free-floating culture thing. There are other reasons to write, and they can be just as innovative, though perhaps they are put to the service of something else. I’m thinking here of what Amiri Baraka once said: “There is no such thing as Art and Politics, there is only life.”

51

KG: Oh, these are much more than little art games. Those turns represent enormously new and significant modes of thinking across vast swaths of culture, deeply changing our worldview. No, these changes are happening far, far outside the box: they are our new folklore.

52

But getting back to these questions you ask: Where are we? What are we doing here? Who are we speaking to? These are things we can never know: connective technology has blown away any sense of being sure that we know anything! Today, all we know is how little we know. For instance, I recently received the following email at UbuWeb:

53

i really enjoyed your site. it made me think about different cultures other than the ones i experience daily living in a small texas town. –meredith

54

Somehow Meredith found her way to Ubu. Ubu refuses to advertise or proselytize: we’re simple here and you’ve gotta find us. 20,000 unique computers — many of them, I’m sure are Merediths — access the site every day. Their lives are changed. But I have no way of knowing who I’m speaking or which of the 5,000 artists whose work is on the site they are downloading. And the artists on the site whose work is being downloaded have no idea who they are being downloaded by and what impact they are having on lives. But, from the small glimpses I get from people like Meredith, I can tell you that the impact is vast and very positive.

55

So, where are we? I really can’t tell you.

56

What are we doing here? We are speaking to legions who comprised a vast, unknown community, one that materializes on occasion when one, for example, does a reading in Europe and — this happens often — they’ll know your work chapter and verse without ever having seen a book of yours. All they know is what’s on the web. And, for many, as I’ve said many times, if it doesn’t exist on the internet, it doesn’t exist.

57

Who are we speaking to? That is something we cannot fathom. Vast acts of community service can be performed to a community of unknowns. Generosity and openness is not contingent upon being together in the same room; nor does it depend on fresh air, nature and sunshine; like Ubu, it can ride on the servers of mammoth corporations and be fueled the neurotic consumption of junk food. Some of us prefer to do good works alone under fluorescent lights in buildings with windows that don’t open; communities and their nexuses are complex, wide and diverse.

58

DS: Ubu contributes an extraordinary resource to anyone who can get to a machine. As it constitutes a vast archive of material — a kind of museum, say — I think what you’ve done is remarkable, and it’s great that you’ve got Meredith to “think about different cultures.” So, of course, generosity and openness is not contingent upon anything. I realize that we’re isolated, framed by our screens, searching. But there’s more than the machine, too. 20,000 unknowns. Located somewhere in space. Scattered across geography. Place, memory, personal narratives, histories — everyone piecing together where they come from with what’s beyond them. If there were an answer to this sense of “where we are,” we could do something other than art. As it is, “where” we are is complicated by issues of geography, personality, psyche, family, and social institutions. “There’s no there there.” And yet, here we are, too. The communal possibilities of the web are vast, indeed, but poetry in that quaint modernist sense asks questions about the subjective experience of these connected isolatos. Somewhere between the subjective search for meaning and the collective hive that organizes that meaning for others, I see art and technology symbiotically related.

59

Who we are speaking to remains an immensely interesting concern, too. Like, I don’t think you are speaking to Meredith: Ubu provides a space she must approach under its terms. And that’s fine. But the terms of the conversation were designed elsewhere for different purposes. Is there an invitation offered with Conceptual Poetry? Are all encouraged to attend the party? As you’ve said elsewhere, you’re invested in art and literary history, and you take direction from that and speak within those coordinates. Meredith is trying to situate herself within those coordinates, too, using her own capacities. Perhaps she would believe your recent claims in Poetry Magazine that Flarf and Conceptual Poetry are now the only games in town: but that doesn’t make it true, and, especially, such claims kind of contradict the lovely sentiment you expressed above about “[v]ast acts of community service” because that service is offered within hierarchies of knowledge and power used to prepare the Merediths of Texas or elsewhere to accept the authority of art and literary history over their own perceptive abilities. The museum’s claims to authority can so easily undermine one’s own senses and native abilities to find out. I guess what I’m saying is that we need commitments to nonliterary or nonart culture, and that the vitality of an art is so only when such commitments are at stake.

60

KG: UbuWeb is not a democracy. It’s a one-way street: we decide what goes there, you take what you need. We don’t listen to user input; we have no community feedback or social mechanisms in place. Our political or social or ethical stance is built around radical and utopian ideas free and open distribution and access for all. Yet 99% of what is submitted is not accepted. But that’s why it’s so good. The bar is set very high according to Ubu’s standards, which are quite rigorous. I’m sorry, but inclusivity for the sake of inclusivity does not make for very good art.

61

DS: Yes, and I’m sympathetic, as I’ve said, to the project. There must be a selective process, of course. But then you have to be willing to work within the power discourse this establishes. And this contributes to a distance between the literary and non-literary, between art and non-art. It can reinforce the age-old problems of aesthetics, taste, and authority. I guess, as our differences are refined, I’m interested in who bears witness to things outside the art house, or the space of the anthology — and wonder about the claims of culturally illegitimate voices and performances, too. Like, what happens to unpopular art? I’m not saying burn down the museum or to slacken its “standards,” but, perhaps, question its function, its relation to other sources. UbuWeb may not be a democracy, but it participates in a digital atmosphere that has been described by many as a democratizing force, and that certainly complicates any authoritative stand.

62

KG: Getting back to something you said earlier, I never made any claims in Poetry that Flarf and Conceptual Writing are the only games in town. I merely suggested that these are two movements are direct investigations toward the question “what does it mean to be a poet in the internet age?” It was not meant to be a survey of the field answering that question, rather it was focused on two groups who intensely employ and embrace the web and its workings in very different ways as the basis of their practices. Now, the fact that I approached Poetry magazine with this idea goes back to what we were talking about earlier with The Whitney. I want the biggest stage I can find for this work. And I adore the idea of such oblique conceptual works and truly “bad” Flarf pieces infiltrating this citadel of conservativism. It’s wonderful and let’s hope that it’s opened the door for this sort of work in the magazine.

63

But here’s what we’re getting at, Dale. It’s clear that we have a wildly divergent sense of the social and of community. I’m not really interested in writing as a platform for the social or to define community. It’s there, but it’s not my main focus. I respect poetry that has a larger scope — I’m thinking of you and Rodrigo Toscano and Jonathan Skinner — but it’s just not what I do. I think this is where it becomes useless to try to read each other’s practices through each other’s lenses. In the end, it’s just a completely different set of concerns. Yet, as someone said on your blog we, in fact, are on the same team. It’s just that we sit on different sides of the bench.

64

DS: But Kenny, you engage in defining communities like UbuWeb and the Whitney and Poetry, and these are “platform[s] for the social,” too. My concern, as I mentioned earlier, is not with the work you do, but in how you frame that work for others and for public consumption. And that framing is crucial, and in it our differences reveal approaches to how we think about poetic presentation and its field of action. As one team player to another, we have more than a bench between us, but to extend the metaphor, we must continue the game according to our own abilities.

65

KG: Our notions of framing are very different and I’m not sure we’ll be able to reconcile those. Yet, I see similarities between us. Reading through the introductions for the various sections in the Slow Poetry feature in Big Bridge, I am sympathetic to many of the concerns and see a lot of overlap. Tom Orange’s “Long Now” piece is very good. It reminds me of Christian Bök’s newest project, which is based around encoding a poem into an amoeba. Christian’s poem has a scope of six million years! Or when Kristin Prevallet proposes “reusing poetry as opposed to creating new poetry,” she goes to the heart of Conceptual Writing. We believe in recycling language. With all the existing language out there, what need is there to make more? Or she also claims “Is my thinking really so magnificent that I need to churn it out, not missing a single thought bubble?” It’s a sentiment which I completely agree with, hence my idea of the “uncreative” and my advocating for appropriation and plagiarism.

66

DS: Yes, your notion of the “uncreative” is provocative and associates with Kristin’s thinking about poetry, certainly, and mine. The “creative” in “creative writing” has really done a lot to isolate poetry from other forms of writing and to give it an appearance of public uselessness. But I would argue too with you and Kristin and say that my thought is important in particular contexts and situations of engagement. To say that my thoughts aren’t important for the poem is to make a profound statement that is in service of thinking, anyway, in a context that demands attention to the burdensome power of mind in art. “Thinking” can’t be escaped but it can be thought against, or thought through, or turned upside down, or occasionally buried, ignored, or betrayed, and this, I think, is a great service of the “uncreative:” to dismantle habits of thought and procedures of writing that associate with the institution of creative writing, not to mention other institutions that determine in one form or other how we are to proceed.

67

KG: We are in the position of having to articulate and shape the discussion about our work ourselves: the critical system is in a shambles, the blogosphere, which has come to be a substitute for any real criticism — is an absolute mess and the prominent poetics bloggers — no names mentioned — in spite of often being wonderful poets, are simply awful critics. So, all we’re left with is the poet to frame their own work. So, I’m often accused of being too strident, too biased, too narrow-minded, to hyperbolic and so forth. But the fact of the matter is that, while I might not be the best voice to represent my interests, I’m pretty much the only one. And I’d rather throw it out there then with all this hyperbole, biases, and polemics to get people talking. No one can possibly expect an artist to be neutral… The critics will come later, but it is up to the poet to get out there first. Indeed, listening to myself speak, there literally still is an avant-garde! How 20th century! But there was no critical establishment representing, say, Marinetti when he was writing, so he had to get out there and scream manifestoes from the rooftops. He was really nuts. But we’re not in so much of a different position than he was 100 years ago!

68

DS: As poets we are responsible for discussing what we do: otherwise we should abide by the virtues of silence, keeping up the mystique of our practice. I say stupid things all the time about poetry. Things that are outrageous and unjustified but in the moment they makes sense and are necessary to say. It’s the difference between saying what is true and what is right or wrong. I’ve had the fortune (or misfortune) to now “formalize” my training in academia. It’s weird to wear two hats, of poet and critic, and I find the impulses behind both to sometimes be in conflict. This is to say I sympathize with your position, though perhaps unlike you, I often feel that I’m walking a razor’s edge, the critical monkey often abusing the poet-acrobat. That said, I agree whole-heartedly: the level of critical conversation particularly online is abysmal. I think that those of us who are for whatever reason compelled to write about art and poetry (rather than just writing or making art — a much better alternative), we (and I’m directing this more at myself — I) should be more responsible to the terms of the conversations taking place.

69

One thing I hope that Slow Poetry may do is to provide an ongoing space that gives no outlines or prescriptions for praxis, but contains accurate critical and contextual possibilities for understanding any individual practice. The ongoing debates about modernism, the avant-garde, popular culture, and the institutions that support or hinder poetic production remain essential to all of our collective labor, particularly now that technology has upped the ante to such a remarkable degree. (Another premise of Slow Poetry is that technology relies on abundant resources, and that we’re entering a period of global contraction: hence, our relationships to technology of all kinds are undergoing a radical change.) So the “slow” in Slow Poetry doesn’t necessarily mean to resist the conditions of the world we inhabit, but to sidestep what isn’t working, or useful — to question the relationships between people and machines, communities and systems of thought and behavior. I hesitate to say anything more about it here because it’s an ongoing thing — a hive resource. But there’s no central platform. Only possibilities and reminders.

70

KG: In spite of your humility and claiming to want to shy away from the spotlight, Dale, you’ve conceived of a very well articulated, compelling platform, one that has won you — in spite of your best efforts — quite a following. And I very much admire your stridency and positioning, as well as your point of view. Slow Poetry, Flarf, Conceptual Writing… three divergent but very prominent strategies that articulate what it means to be a poet in this moment. And I feel the best art can do is to reflect the times in which its been made. On that count, all three movements are doing a great job. But this moment is fleeting. If I was a young poet today surveying the field, I’d probably see the limits of these three discourses: I’d wanna shred ‘em. And the best thing that could happen is that they will spawn equally intelligent, oppositional strategies — we can only hope: may a thousand flowers bloom.