| Jacket 38 — Late 2009 | Jacket 38 Contents page | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 6 printed pages long.

It is copyright © Eric Mottram Estate and Jacket magazine 2009. See our [»»] Copyright notice.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/38/jwb07-mottram.shtml

Back to the Jonathan Williams Contents list

The following essay was first published as the introduction to Jonathan Williams’ Niches Inches: New and Selected Poems (Jargon 1982) and is reproduced here with the kind permission of the Eric Mottram estate and Jargon Society.

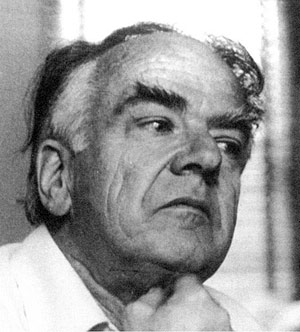

Eric Mottram

1

Jonathan Williams is one of the finest American poets of this century. That should be enough to say but it is not. These days he finds it difficult to find a publisher for his books, other than himself: a sufficient comment on the state of publishing on both sides of the Atlantic. He has asked for an introduction from a constant reader who has been under his tutelage at least since purchasing The Empire Finals at Verona in 1963; when Williams actually performed the Stan Musial poem in that book, poetry began to be realized in a new way. In the Olson “Funerary Ode” he says that “the poem is no place for polite usage only,” and not surprisingly March is his month: “...engendering green in the groundwork we work/ to prepare a Spring in ourselves; to air the sound/ in ourselves.” Probably rightly, he has given up preparing it anywhere else; he might modestly be surprised that he still prepares it in others. He names Olson Orpheus; in his Elgar poems Orpheus is Eros; but then that pairing that makes for a necessary home is to Williams also Orphic — an alternative to those isolations instanced as the voice of the bardic executed floating head:

2

...whose juices come

from the hill

and spill into me

and make me a month’s mouth—

a goat-foot in new greenery

I love you and would

care for you—

3

Williams’s technique, if anyone still does not know, is nonpareil. As The Times (London) reported him in 1970: “Poetry to me is a kind of field — a place in which things happen. Our dear old friend Freud said wit is the playground of the mind. I’m interested in poetry as a playground. I’m interested in walking across the page, making football moves across the field.” The past poets are active in him: “Tradition is in us/ like the sun/ ‘Sin is/ separation’”.

4

Dionysos unnerves with destructive skills as well as through nature and erotics, the presence of body as an extension of mind, mind of body. But Williams is adept, in day to day conduct as well as in his poetry, at the camouflage of gentility for purposes of invasion. Decorum holds Eros in art and good manners. In each book there lies a recognition that in releasing Eros we may well sink beyond creative individuality into freakishness, madness, religious mania, nymphomania and artistic self-regard — let alone the crude political ego-mania of certain Southern senators. Williams knows, too, that the Stonewall Riots of 1969 in the United States were only a tactical victory, a cultural explosion rather than a cultural change — a phrase of his in a letter to The Times (New York) in 1968. But it is doubtful if he would use the word culture much nowadays, if at all — for the same reasons that he writes: “The words male and female must have been invented by the same crowd that talks about Truth and Beauty.” If you believe in variety and range of pleasure to defeat abstraction and enslavement to current fashion, you have to reach deliberately the rich alienation from stupidity and impotence Williams’s poetry articulates.

5

The present selection from work published between 1969 and 1981 is expressly for the British, who certainly need it. Our tribal nationalism despises his definition of erudition — a knowledgeable set of passions for skill and individuality, a range which for him is enlivened with Mahler and Midler (Bette), Samuel Palmer and Ronald Books Kitaj, Mervyn Peake and Theakston’s ‘Old Peculier’ [sic], Ross Macdonald and Franklinia alatamaha (and Wm Bartram’s drawing of it), Oldenburg and Ruggles. His language does not so much stabilize this exuberance as guarantee its selective joys in another kind of athletics. Appreciation without greed or imposition is as rare as love without the will to domination and submission, as he is well aware.

6

Williams is fond of being useful by prefacing his books, and lists of his books, with pronunciamentos from admired language masters in every field. Here is a short one culled from two interviews he gave with Tom Meyer in 1974 and 1975:

7

I am a poet and a man who lives by Catullus’s little song, ‘Odi et Amo’.

Sex is one form of heat, poetry another. Our encounters are never entered without openness... Poetry is about paying close attention to the particulars and not going moralistic, diffuse, intellectual, remote. “Every man in his life makes many marriages,” said Sherwood Anderson. Not with lovers only, but with beloved plants, hills, sacred places, animal spirits, rivers, etc...

Poetry is not under obligations to Sociology. As a matter of fact, I agree with one of Charles Olson’s primary preachments: the poet’s only obligation is to make fresh lines.

Play is far more, finally, instructive than Deep Talk... Decorum is an operative word.

We choose to live on the margins of this society and have somehow managed to do so. “Living well is the best revenge,” someone said.

8

Decorum in poetry is the good manners not to waste the reader’s time, space and energy. Williams concentrates on making music and speech rhythms work with visual coordinations and disjunctions. His urge, increasingly, is to condense to the state of epigram (his longer poems are often branches of epigrams), clerihew, pun chains, palimpsests in parvo, brief acts of what Joyce termed verbivocovisual on the word. His ear for people’s speech — ours as well as theirs — enables him to record impulses to idiosyncrasy he finds around him into poems of discovery rather than acceptance. This is part of his admiration for creative idiom that moves fearlessly into the eccentric contrary to the centricity of consumer-spectator society and its replacements of taste by fashion and money. His humanistic politics begins here, applying himself to the frontiers of what the bourgeois fears as ‘bad taste,’ or the freed body striving for survival against that sado-masochism which passes these days for the social. The poem of decorum is therefore exuberant and sophisticated, agile and jovial. But social criticism is everywhere, a proper intolerance which often takes the form of a geniality barely masking a loathing for hypocrisy, cruelty and ignorance: Pope’s Dullness.

9

The poem that is also a product of walking, music of all kinds, and photography cannot afford to neglect good boots, good performance skills, and good lenses. A product, too, of various forays into the necromantic realms of restriction and abstraction. The trained man with a Rolleiflex and a Mamiyaflex organizes his eyes with fundamental technology against the unruly mass of men in noisy desperation. The decision as to how much subjects are posed is, naturally, the point at which the note to his Portrait Photographs begins a short discourse on selection and record. In his note for Photographs by Raymond Moore, Williams intimates a lifelong position — that the photographs are photographs, “images in service to Seeing. Not in service to Sociology, The Class System, And Excess of Rationality, Cosmic Adumbrations, Self-Expression, Masculinity, Document, etc., etc.” He should know: he is a firstrate photographer (we can ignore the rude, footling review of Portrait Photographs in The Listener by a mainliner of British Cultural Control). Williams also says of Moore, he is “a man constantly informed by music” — and the poet, too, listens as much as he sees. As a performer of his own poetry, he transmits his masterly timing of the lens to a gifted speaker’s timing of the voice. But it is also a comedian’s gift for wit as a means to reveal, briefly and suddenly, both pretensions and the void under them. “Am I saying that art is one of the best ways to salvage one’s days on this planet?” he writes, as a “North Carolinian/ Cumbrian person” — “Blame it on my Welsh ancestors and let’s go back to the images.”

10

Williams accurately claims that he has “absolutely no known audience — except a very few friends who are not bored silly by this odd substance called Poetry.” You notice the word substance and then you notice that the few include — on record — Buckminster Fuller, Guy Davenport, William Carlos Williams, Bunting, Robert Kelly, Robert Duncan, Gilbert Sorrentino, Hugh Kenner... One reason we like him is that he plays on our storage systems and our memories of pleasure and abhorrence, without clamping us in a vise of dogma. His wit is a disclosure, a way to make us feel good by creative participation in an art. Nature is not witty; we can be; sight and speech combine in the Williams poem to make a phenomenology of perception as professional as it is honest. How many poets can make us laugh into a state of involuntary abandon, and then return to the causes? Sometimes he condenses perception into a means for a guffaw at a rather obvious recognition, but rarely, and it is usually at the expense of some literary or sexual pomposity.

11

He has received some good appreciations: the Truck issue for his 50th birthday, Ken Irby’s article in Parnassus, the Vort issue he shared with Fielding Dawson. But the best introductions are his own selections of his work in books like Elite/Elate Poems, Selected Poems 1971-75 (1979), an excellent system of entrances, settings, and poems, and let it be said immediately: few poets have that joy in their ability which destroys artistic egoism. Perhaps living double-housed in Highlands and Corn Close has given a necessity to know exactly where he is? The poems, re-read from their earliest appearances in the 1960s, have an urgency which moves — given the time we live in — the need both to appreciate and resist environments. He is fond of making lists of what he likes, or boxing up maxims, turning oracular statements like some breviary. But his prosody itself is a resistance to both the imitative laxities of ‘open field’ poetry and the dull bondage of Hardy, Thomas and Frost, or the Auden and Lowell ironies which dominate official British poetics. Williams could be a rejuvenatory resource. Concrete poetry, found poetry, treated texts, the clerihew, riffs, Sitwellian systems of rhyme, meticulous limericks — he is as professional an inventor as Picasso or Ives.

12

But this North Carolinian/ Cumbrian person is also a valuable appreciator and interrogator of Britain. Davenport wrote in his introduction for An Ear in Bartram’s Tree (1969):

13

A pattern of artists emerges — Blake, Ives, Nielsen, Samuel Palmer, Bruckner — and (if we have our eyes open) a whole world. It is a world of English music, especially Edwardian Impressionists and their German cousins Bruckner and Mahler, of artists oriented toward Blake and his circle but going off by centrifugal flights into wildest orbits, men like Fuseli, Calvert, and Mad Martin. The poet’s admiration for Edith Sitwell will have something to do with this exploration of English eccentricity, and the poet’s Welsh temperament, and, most clearly, Blake himself. The artist is aware of a heritage not only because, like the rest of us, he recognizes it in his origins and values, but because he is consciously adding to it.

14

This is why Williams moves among us like an ideal anthropologist who does not disturb the natives at their rites, but with an amazed judiciousness even eats some of their food, and actively likes Balfour Gardiner and Arnold Bax. Everywhere he walks and drives he stalks the British object (Barbara Jones was an early London friend), ear and eye collecting with an explorer’s delight and apprehension at being up the Amazon. Sex is everywhere — “I haven’t seen the territory yet that can’t be sexualized or examined for its poetic cuisine, or its birds, or for its dialects.” He delights, too, in artists’ burial places and in epitaphic epigrams for their demises — not to idly memorialize but to ensure that the elite do not depart without greeting and recognition, and to re-establish a certain hierarchy of value, clear, too, in his foreword to Untinears & Antennae for Maurice Ravel: “The function of poetry, according to Louis Zukofsky, is to elate and record. I have no argument and can offer no improvement. For me each poem is both elegy and celebration. A poem is a linguistic, phonetic, graphic object.”

15

Williams is American in his inclination to de-centered openness to form and subject; British — may we say?—in his love of that which resists levelling: the note for Adventures With a Twelve-Inch Pianist Beyond the Blue Horizon (dedicated to Bette Midler) includes: “If male friendship is not a subject that interests you (in which case you are a super-cosmic titanism from a distant congeries of galaxies, like H.P. Lovecraft)... you should be listening to Pat Boone or Ike Turner or Oral Roberts.” This poet is ready to be amazed, but he remains as alert on watch as a Mailer patrolman, ready to kill in the world of signs. Increasingly his poems curtail into their own worlds and then flash steady compressed signals — as if lengthy discourse merely spread towards some blurred vanishing point. The poems move toward something like photographs, in fact — silent images to be silently gazed at (the series of poemcards as objects, the Furnival series punning visually and verbally on Anton Bruckner, Gertrude Stein and others of the elite), as we gaze at the gazes of the artists in Portrait Photographs. The satirical gaze of Williams’s poems frequently engages outlawed sexualities, and challenges the faked ignorance of the self-consciously respectable and up-tight. But the sexual poems are also strategies for holding together the body’s loves and sensuousness in language. Tenderness is not exposed to vulgar sentimentality but firmly embedded in the complexity of its origins. Where the pornographer fantastically isolates the body’s needs from the practical and social, Williams respects the total perceptive scene: things as they are, with allegorical meaning resisted. In the Vort issue he speaks of “neighborliness to materials... communities... ecosystems.”

Eric Mottram (1924-1995) was an English poet, critic and editor associated with Bob Cobbing’s Writers Forum and the British Poetry Revival. Retiring from King’s College London in 1990 with the title Emeritus Professor of English and American Literature, Mottram served as editor-in-chief of Poetry Review (London) from 1971-77. A close friend to Jonathan Williams, Mottram like Williams took a decidedly transatlantic approach to the study of contemporary Anglophone poetry which exacerbated what Peter Barry and other critics now regard as the Poetry Wars of the 1970s. His archive, catalogued by poet Bill Griffiths, is presently maintained at King’s College.