| Jacket 38 — Late 2009 | Jacket 38 Contents page | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 17 printed pages long.

It is copyright © Tom Patterson and Jacket magazine 2009. See our [»»] Copyright notice.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/38/jwd03-patterson.shtml

Back to the Jonathan Williams Contents list

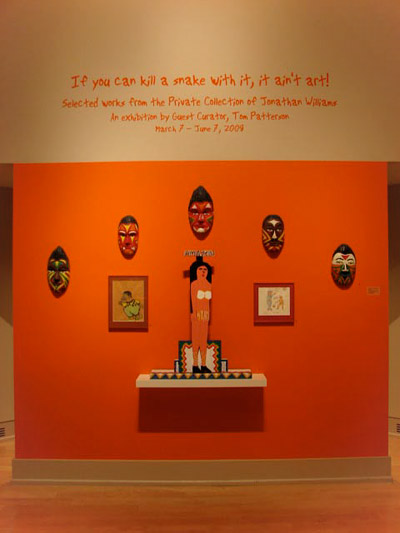

Eddie Owens Martin (aka St. EOM): Five Pasaquoyan Masks, early 1980s, painted concrete, James Harold Jennings Amazon, late 1980s, painted wood

Preliminary Note:

The following essay was originally written as a contextual backdrop for the exhibition ‘If You Can Kill a Snake with It, It Ain’t Art: Selected Works from the Collection of Jonathan Williams’ which I curated during what turned out to be the last year of Williams’ life. The premiere venue was Appalachian State University’s Turchin Center for Visual Arts, in Boone, North Carolina, where the exhibition opened on March 7, 2008, the day before Williams’ seventy-ninth birthday. As it turned out, sadly, the occasion found him in deteriorating health and close to his home in a hospital where he remained for nine more days until his death on the night of March 16. The exhibition remained at the Turchin Center until early June and, at this writing, is on view at the Green Hill Center for North Carolina Art in Greensboro, North Carolina (January 23-March 22, 2009). This essay is envisioned as the central text for a color-illustrated catalog of the exhibition projected for eventual publication by the Jargon Society. Williams remained very much alive at the time of the essay’s completion, and the concluding paragraphs provide a snapshot of his final months among us mortals. Accordingly, I’ve chosen to retain the original present tense, referencing Williams throughout as a still-living presence, as in many ways he will remain for those of us fortunate enough to have known him.

– TP, January 2009

Epigraphs from two photographers:

To worship beauty for its own sake is narrow and one surely cannot derive from it that aesthetic pleasure which comes from finding beauty in the commonest of things.

– Imogen Cunningham, as quoted in the introduction to Williams’ Blues & Roots / Rue & Bluets: A Garland for the Appalachians

If you can kill a snake with it, it ain’t art.

– Lyle Bongé

1

Lyle Bongé’s bodacious zinger of an esthetic credo is one of the more memorable lines in Jonathan Williams’ collection of favorite quotations, a bit of inspired nonsense reflecting a strain of southern-fried dada humor that Williams and Bongé both appreciate. Since it plays on the perennial issue of how art is defined, it seems a pretty good fit for an exercise that’s all about Williams’ eye and what attracts it.

2

Williams’ literary and publishing endeavors have been fairly well documented and celebrated in print and in several exhibitions. [1] Less widely recognized and appreciated to date is the extent of his engagement with visual art, and the fact that he has been involved with art and artists for at least as long as he’s been writing poetry. An examination of his career’s visual dimension reveals important connections between his art pursuits and his more widely known efforts and enthusiasms. Something of the range of his visual sensibilities is reflected in the invariably handsome, always distinctive designs of the Jargon books he has published over the years. [2]

3

He has also maintained an active career as a photographer since the early 1950s, specializing in informal portraits of artists and writers and views of artists’ graves and visionary-art environments. [3] Over the last sixty-some years he has been steadily collecting objects that have caught his sharp eye or been given to him by the many artists he has known during that extended interval. His collection is born of friendship as much as esthetic affinity, and the scale of its holdings is consistent with domestic space, always conducive to close viewing.

4

I’ve had the pleasure of getting to know this collection over more than thirty years of friendship and professional association with Williams and his companion, fellow poet Thomas Meyer. I’ve visited their mountainside home in Macon County, North Carolina, on a few dozen occasions, including five or six visits over the last year, specifically for the purpose of taking a more systematic look at what’s usually displayed on the walls, shelves, floors and tabletops. I’ve inventoried more than three hundred pieces in the house and a smaller nearby cottage on the property, and from that number I selected about two hundred outstanding ones for the traveling exhibition ‘If You Can Kill a Snake With It, It Ain’t Art’. In this essay I hope to sketch out something of the personal history behind this remarkably wide-ranging collection and comment on how it has evolved.

5

Williams’ literary and visual interests have been intertwined from the beginning. The first artworks he found appealing were illustrations in his favorite children’s books — L. Frank Baum’s ‘Oz’ series, Rudyard Kipling’s Just So Stories, and Beatrix Potter’s self-illustrated tales. Growing up an only child in Washington, D.C., he attended St. Alban’s School, the prestigious private academy where senior contemporaries among the student body included Gore Vidal. Williams’ memories of his six years at St. Alban’s include classes in which art teacher Dean Stambaugh instructed ten or fifteen students in still-life and plein-air landscape painting and led them on field trips to the Phillips Collection. As an adolescent, before he began to cultivate literary ambitions, Williams aspired to be a painter.

Mark Steinmetz: Skywinding Farm Gate, late 1990s

6

In the early 1940s his parents bought a forty-acre farm in the Southern Appalachians where they built the house he still lives in, about ten miles outside the resort town of Highlands. His father, a North Carolina native and professional filing-system designer, gave the property the poetic name Skywinding Farm, and it initially served as the family’s second home. Williams took advantage of their summers there by working directly from nature, sketching waterfalls and other features of the local landscape. Back at St. Albans in the fall, he made oil paintings based on these sketches. Surviving works from his teens also include drawings of scenes from Disney’s Fantasia and a creepy surrealist landscape painting inspired by H.P. Lovecraft, a favorite writer in those years.

7

After graduating from St. Albans, Williams entered Princeton University. He recalls the year and a half he spent there as a fallow period for his painting but acknowledges having absorbed useful insights into Byzantine, classical Chinese, and Italian Renaissance art in the art-history classes. It was also at Princeton that he made his first forays into art collecting. He bought an affordable Henri Matisse lithograph of a woman’s face from a traveling print dealer who regularly visited the Ivy League schools. And — as a ‘bribe’ to keep him at his studies, according to Williams — his father bankrolled his purchase of Georges Rouault’s aquatint etching The Yellow Clown from a New York gallery.

8

Williams used the Rouault etching as an excuse to meet a writer and artist whose work he had recently discovered, namely Kenneth Patchen. Having read of Patchen’s interest in French modernism, Williams wrote to him at his home in Old Lyme, Connecticut, and offered to lend him his fresh art acquisition. Patchen wrote back to accept the offer, and Williams hand-delivered the Rouault print to him. (Williams isn’t sure when he finally got it back but thinks it was probably in the late 1950s.) Around the time of their initial meeting, Williams bought the first of several limited-edition Patchen books he has owned, each incorporating Patchen’s hand-painted images.

9

Williams didn’t like Princeton, and he dropped out in 1949, but he persevered with his art studies. Returning to D.C. for a few months, he briefly studied painting with Carl Knaths at the Phillips Collection. He spent most of 1950 in New York, living in the West Village and studying graphic art with Stanley William Hayter at Hayter’s Atelier 17. Early in 1951 Williams left New York for Chicago, where he enrolled for one semester at the Institute of Design. It was there he produced his final statement as a painter — an untitled abstract-expressionist exercise he made by dropping a bucket of tar out a second-story window onto a sheet of white cardboard. He’s still fond enough of it that it hangs in his home alongside some of his favorite contemporary folk-art pieces. Also during his semester in the Windy City, at the site of a Louis Sullivan building undergoing demolition, Williams found a fragment of Sullivan-designed terra cotta ornamentation, a segment of stylized vines in relief, which he subsequently framed and still prominently displays in his home.

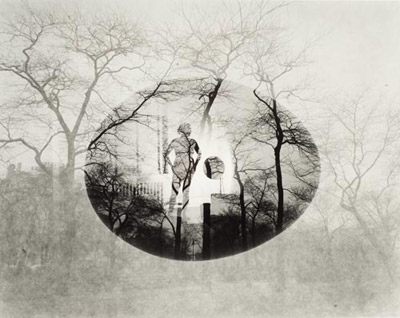

Eleanor, Chicago: Harry Callahan, 1953

10

During his brief stint at the Institute of Design, Williams made connections with several individuals who would influence his future creative trajectory. One was M.C. Richards, a writer who would later become a potter, and from whom Williams would collect a few distinctive vessels. Williams met Richards when she paid a visit to the institute on behalf of Black Mountain College, where she was then teaching. [4] She was a charismatic figure, and her presentation about the school left a strong impression on Williams. The other two key influences on his path to Black Mountain were photographers Art Sinsabaugh and Harry Callahan, who taught advanced photography courses at the institute. It was their work — Callahan’s in particular — that prompted Williams to take an active interest in photography. As a beginner at the medium, he was ineligible for enrollment in their Chicago classes, but Callahan and fellow lensman Aaron Siskind had been hired to teach under less restrictive circumstances that summer at Black Mountain. Williams followed Callahan’s suggestion that he sign up to study with them there. Over the next few years Williams would buy the first of a number of prints he owns by these photographers.

11

Late in the spring of 1951, before settling in at Black Mountain, Williams traveled to the West Coast. During a visit to Big Sur he spent a few hours with Henry Miller, who gave him a small blue jewel of a watercolor. In San Francisco Williams collaborated with printmaker David Ruff, whom he knew from Hayter’s New York atelier, to produce fifty copies of a broadsheet in which a copper-plate engraving by Ruff accompanied Williams’ poem ‘Garbage Litters the Iron Face of the Sun’s Child’. Williams doesn’t think much of the poem, in retrospect, but the broadsheet became the first publication of the Jargon Press, an operation which from the start paired contemporary visual art and writing. Williams brought copies of Jargon #1 with him to Black Mountain, where he quickly began learning what he could about photography from Callahan and Siskind. A secondhand Rolleiflex that Siskind located for Williams became his primary art-making instrument, replaced in subsequent years by other similar cameras and eventually augmented by various Polaroid models.

12

More influential than any visual artist on the creative transformation Williams underwent at Black Mountain was poet Charles Olson, who taught writing and related courses at the college and had recently been installed as its rector. In interviews Williams has acknowledged the powerful impression Olson’s poetry, dynamic personality, and teaching made on him as a young man still in search of his métier. Stimulated in part by Olson’s classes, Williams began to devote increasing attention to his own poetic efforts and to his fledgling press, an enterprise that Olson encouraged. In Olson’s classes Williams met fellow student Joel Oppenheimer, who had learned to operate Black Mountain’s in-house letterpress. The two combined forces to produce 150 copies of the second Jargon broadsheet, in which Oppenheimer’s poem ‘The Dancer’ is augmented with a drawing by Robert Rauschenberg, then an art student at the college. The notebook-size, abstract drawing consists mainly of freehanded arrows pointing in myriad directions. Like many other works reproduced in subsequent Jargon publications, it entered Williams’ collection, although he sold it a few years ago.

13

Williams retained his student status at Black Mountain beyond the summer session and into the following academic year. In 1952 he and Oppenheimer collaborated to produce the third and fourth Jargon imprints — The Double-Backed Beast (text by Victor Kalos and drawings by Dan Rice, both Black Mountain students) and Red/Gray (poems by Williams and a drawing by Paul Elsworth, formerly a fellow student at the Institute of Design). Later that year, though, Williams’ activities at Black Mountain were interrupted by the draft. Having been classified a conscientious objector; he was assigned to non-combatant work for the U.S. Army Medical Corps in Stuttgart, Germany, for a term ending in 1953. During that interval, he used an inheritance of $1,500 from a recently deceased family friend to finance small-edition Jargon books by Creeley, Olson, Patchen, and himself. Accompanying the text for Creeley’s book, The Immoral Proposition, were drawings by René Laubies, a French artist whom Creeley knew and Williams met while in Europe. (Williams still owns a Laubies painting from the same period). Williams rendered the calligraphy for Olson’s The Maximus Poems / 1–10, and Patchen created unique paintings for each of fifty copies making up the special edition of his Fables & Other Little Tales. Drawings for Williams’ book, Four Stoppages / A Configuration, were made by Charles Oscar, an artist he had met at Black Mountain.

14

Williams made one art purchase while in Germany, albeit at no significant expense. At a Stuttgart gallery he paid twenty-five dollars for a photograph by László Moholy-Nagy, which he sold about forty years later for a substantial profit.

15

After returning to the United States in 1954, Williams made Skywinding Farm his home base but over the next couple of years traveled often to Black Mountain, about 100 miles to the east. At the time the college was on its last legs, its population reduced to a bare-bones faculty and a handful of students. He made a number of photographs at the school in those years, and his Jargon Press published new books by Creeley (All that is Lovely in Men, 1955) and Olson (The Maximus Poems / 11–22, 1956), both still teaching there. Black Mountain’s final year, 1956, also witnessed Jargon’s publication of four more books, including Will West, the first novel by Paul Metcalf, then living near the college. The other three were by poets who lived far from North Carolina and had no connection with Black Mountain — Louis Zukofsky, Irving Layton, and Michael McClure, for whose first book, Passage, Williams created special calligraphy.

16

Visual artists among Black Mountain’s last holdouts included Joseph Fiore and Dan Rice, both nominally teachers at that time, as well as painting student Jorge Fick. A couple of Rice’s works on paper from that period remain in Williams’ collection, as do two small, later paintings by Fick. Rice provided drawings for Creeley’s second Jargon book, and more than a decade later made drawings that Williams reproduced on the cover of Ross Feld’s Jargon-published Plum Poems (1972). Rice’s work bore the boldly gestural stamp of New York School Abstract Expressionism, two of whose leading exponents — Willem de Kooning and Franz Kline — had taught at Black Mountain in the years before Williams arrived there. Abstract Expressionism’s leading critical advocate Clement Greenberg had also taught briefly at Black Mountain prior to Williams’ arrival and Williams remembers reading Greenberg when the school was in its final months of operation.

17

After Black Mountain closed, Williams started to establish the pattern of geographically wide-ranging activity he would follow for the next forty years. Crisscrossing the country in a Volkswagen [5] loaded with Jargon publications, he offered them for sale at bookstores and universities where he arranged to give readings. Staying with friends and literary or art-world connections along the way, he subsidized his publishing efforts and his travels by collecting fees for his readings, soliciting paid subscriptions for forthcoming books, and occasionally selling photographs or other works from his growing art collection.

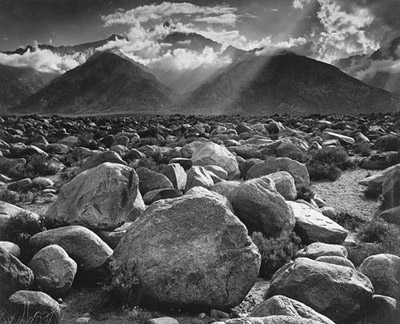

Mount Williamson from Manzanar, Sierra Nevada CA, 1944, Ansel Adams

18

Photography began to occupy more of Williams’ attention in the late 1950s, thanks in part to connections he made on another trip to the West Coast. He stopped on the way and met Frederick Sommer, then living in Flagstaff, Arizona; and shortly thereafter met Sommer’s fellow photographers Ansel Adams, Wynn Bullock, Brett Weston, and Edward Weston, all living in or near Big Sur at the time. Williams acquired photographs by all of them, and he made his own photographs of them, as well as informal portrait shots of other writers and artists he saw during that trip. He revisited Henry Miller at Big Sur, and Kenneth Patchen, then living in Palo Alto, and acquired several Patchen watercolors of fanciful beings. Within the next year he published Miller’s The Red Notebook (1958), with drawings by Miller and an informal portrait photo of the author by Bullock; and Patchen’s self-illustrated second and third Jargon books — Hurrah for Anything (1957) and Poem-Scapes (1958).

19

Williams also visited Los Angeles during that West Coast trip, motivated in part by a desire to see and photograph Simon Rodia’s domestic yard environment known as the Watts Towers — Gaudiesque spires encrusted with broken crockery and rising above the city’s Watts neighborhood. An Italian immigrant and self-taught architect, Rodia had several years earlier abandoned the site. Williams’ visit to Rodia’s Towers marked the beginning of an ongoing interest in vernacular art environments.

20

In keeping with his other activities of the early post-Black Mountain years, Williams published several books that reflected his growing interest in photography. Reproduced in the eleven other books published under his Jargon imprint from the late 1950s through the mid-’60s were images by his former teachers Callahan and Siskind, as well as photographs by Robert Schiller, Sinsabaugh, Henry Holmes Smith, Sommer, and Williams himself.

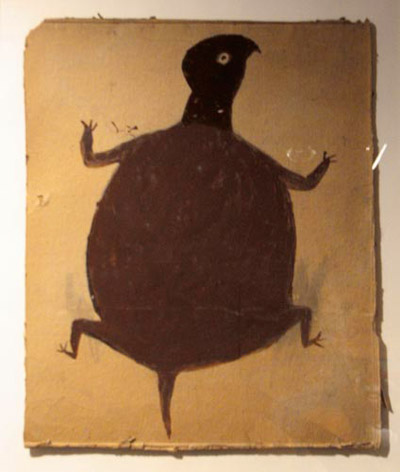

Bill Traylor: Untitled (terrapin), 1940s, ink, watercolor, and pencil on cardboard

21

The latter part of 1957 and the beginning of 1958 found Williams back in D.C. and frequenting the Library of Congress in order to research the Etowah Indian Mounds, the 1,000-year-old remains of an important American Indian city and ceremonial complex on the Etowah River in northwest Georgia. It was a site that held special personal meaning for him due to its location on land that in modern times had been owned by his maternal grandmother Georgia Tumblin, until its acquisition by the Georgia Historical Commission and designation as a state historic site in 1953. In his youth, several years before he began collecting modern and contemporary art, Williams had collected carved stone tools and other artifacts he found on his grandparents’ farm — objects that remain in his possession.

22

During the interval in Washington, Williams met Ronald Johnson, an aspiring poet studying literature at George Washington University. Their common interests and mutual attraction soon developed into a relationship as domestic and traveling companions that lasted for ten years, during which Williams’ Jargon Press would publish Johnson’s first book. From the late 1950s into the early 1960s they lived for periods of a few years or several months at a time in New York, North Carolina, and England. One of their early joint ventures, in 1961, was an ambitiously conceived hiking trip along 1,400 miles of the Appalachian Trail, from Georgia to New York State. The first of many extended walks Williams would take, it significantly influenced his view of the world and had a big impact on his work, yielding what he has referred to as his peripatetic poetic method: ‘always on the go, always on the look-out’. [6] He took the same approach to collecting art — ears and eyes open, picking up what caught his attention and captured his fancy. The sources and subjects in his writings run the gamut from high culture to vernacular culture — ‘refinement’ to ‘vulgarity’ — a range also reflected in his visual esthetic, as evidenced by the art he lives with.

23

Late in 1961 Williams and Johnson made their first trip to England, which they liked well enough to continue living in London throughout 1962. Among the new friends and acquaintances they made there was American expatriate artist R.B. Kitaj, with whom Williams soon collaborated on a couple of publications: Kitaj created the wrap-around cover collage for Williams’ book Lullabies Twisters Gibbers Drags (1963), and a series of sixteen silk-screens to accompany Williams’ poetic sequence inspired by the music of Gustav Mahler. The latter collaboration, Mahler Becomes Beisbol, was issued in 1965 by London’s Marlborough Gallery as a limited-edition folio. More than ten years later Williams’ reproduced Kitaj’s pastel portrait of British poet Basil Bunting as the cover of the Jargon festschrift Madeira and Toasts for Basil Bunting’s 75th Birthday (1977).

24

Williams would return to England often over the next forty years, eventually establishing a regular summer residence in the Pennine Dales of Cumbria. His headquarters there since the late 1960s has been a farmhouse whose purchase and restoration he oversaw for its American owner Donald B. Anderson, an oil-company executive and arts patron from New Mexico.

25

In England Williams was also introduced to native British artists in whose work he took a strong interest, including writer and artist Mervyn Peake as well as visual artists John Furnival, Glen Baxter, and David Hockney, all now represented in Williams’ collection. In the 1970s Furnival made drawings for Thomas Meyer’s The Bang Book and Staves Calends Legends, both published by Jargon, as well as three of the Jargon postcards Williams began publishing after 1975. Much later, in 1983, Baxter would provide the cover drawing and frontispiece for Williams’ The Fifty-two Clerihews of Clara Hughes, which I published in Atlanta under the Pynyon Press imprint. And Hockney sketched an informal portrait of a mustachioed Williams smoking a cigar and looking intense — a drawing he gave to Williams.

26

The 1960s and ’70s also brought Williams important new contacts among artists and literati back in the United States, including several he met during residencies at the Aspen Institute in Colorado and North Carolina’s Penland School of Crafts. Three key figures whose paths he first crossed during those years — writer Guy Davenport (also an adept draftsman) and photographers Ralph Eugene Meatyard and Guy Mendes — all happened to live in Lexington, Kentucky. Williams took an interest in Meatyard’s photographs after a mutual friend introduced the two men while Williams was visiting Lexington in 1960 or ’61.

27

Davenport’s mail order for a Jargon book in 1963 prompted Williams to strike up what became a long-running correspondence with him, and the two met in person for the first time in 1965. [7] In the following year Williams published Davenport’s book Flowers and Leaves, which featured two of Meatyard’s photographs including an author’s portrait. In 1969 Williams reprinted Davenport’s essay Do You Have a Poem Book on E.E. Cummings? — originally published in the National Review — as a sixteen-page chapbook illustrated with one of Davenport’s drawings. That same year, Davenport’s portrait drawings of Ferdinand Cheval and Raymond Isidore — the creators of visionary yard environments that Williams and Ronald Johnson had visited in France — appeared in Johnson’s Jargon-published booklet The Spirit Walks, The Rocks Will Talk. One of Meatyard’s photographs was reproduced on the cover of writer Douglas Woolf’s Spring of the Lamb, a Jargon book from 1972. And in 1974 Williams published Meatyard’s The Family Album of Lucybelle Crater, a book of deadpan portraits of the photographer’s friends and fellow Lexingtonians (including Williams, Davenport and Meatyard’s wife) all wearing grotesque rubber Halloween masks.

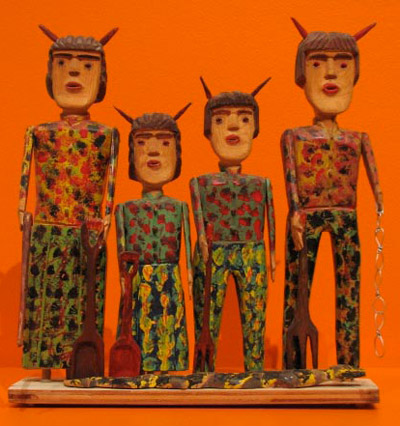

Carl McKenzie: Devil Family with Serpent, early 1980s, metal wire carved and painted wood

28

It was also in 1974 that Williams published his first collaboration with Mendes, a photographer, writer and — at that time — relatively recent graduate of the University of Kentucky. In the fold-out poster publication, Who Is Little Enis?, Williams’ uproariously bawdy poem in homage to Carlos Toadvine, aka ‘Little Enis’ — an overweight, alcoholic rhythm’n’blues singer who performed at strip clubs and honky-tonks in and around Lexington — is imprinted on a blue-hued, stylized phallus under Mendes’ photo-portrait of Enis posed in front of his Cadillac. A few years later, in 1979, several of Mendes’ photographs would be featured in Williams’ Jargon-published collection Elite / Elate Poems (1971-1975). Making another appearance in Mendes’ cover photo, Little Enis poses with his guitar and a group of strippers in front of a Lexington strip-club marquee.

29

In 1965, during a visit to Kentucky’s Berea College, Williams first saw the late Doris Ulmann’s Depression-era photographic portraits of rural mountain people. Ulmann’s assistant during her arduous travels in the Southern Appalachians had been John Jacob Niles, the American ballad singer and folk-music scholar. A visit with Niles in 1967 at his home in Lexington convinced Williams that the photos needed to be widely seen, leading to Jargon’s publication of The Appalachian Photographs of Doris Ulmann (1971). Williams owns a print of one of the photographs, a portrait of ‘Aunt’ Lou Kitchen at her spinning wheel, made after Ulmann’s death, from one of her glass negatives archived at Berea.

30

Another region-centric photography book that Williams published in the early 1970s is The Sleep of Reason (1974), devoted to Lyle Bongé’s darkly outrageous images of Mardi Gras in New Orleans. Like Williams, Bongé is a native southerner — in his case from Biloxi, Mississippi — who attended Black Mountain College. In 1964 he and Williams drove across North Carolina with the aim of collaborating on a book inspired by their travels. The project was eventually shelved, but Williams still has a couple of the photographs Bongé made during their travels, including one that eventually made its way into the Jargon-published collection The Photographs of Lyle Bongé (1982).

31

While continuing to pursue his photographic interests, including his own camera work, Williams began to pay increasingly close attention to contemporary variations on folk or vernacular art. As early as 1960 or 1961, not long after he first saw Simon Rodia’s Watts Towers in Los Angeles, Williams visited folk potter Lanier Meaders at his shop in Cleveland, Georgia, about fifty-five miles from Williams’ home in North Carolina. Making his wares with clay dug from a local river bank, Meaders carried on a tradition begun by his grandfather. Williams bought one of the comically grotesque face jugs for which the potter later became widely known. As evidence of Williams’ sustained attention to such art forms, more than thirty years later he bought two more elaborate figural pots by Lanier’s nephew Clete Meaders.

32

In 1969 Williams visited self-taught artist Clarence Schmidt’s ridgetop environment in New York’s Catskill Mountains. By that time Schmidt’s slapdash seven-story house had been destroyed in a fire, but Williams recalls finding the artist at work coating the trees in his ‘Silver Forest’ with aluminum paint, and he documented the visit in photographs. [8]

33

In Wolfe County, Kentucky, in the early 1970s, Williams met self-taught wood sculptor Edgar Tolson. A lapsed preacher who had fathered twenty-two children and served a year in prison, Tolson began making stylized figural carvings in the late 1950s while recovering from a stroke. In the ensuing years his work was discovered by art professors at the University of Kentucky and began to gain a national following. The tableau that Williams bought from Tolson, depicting Adam’s and Eve’s expulsion from the Garden of Eden remains one of the best and most important contemporary folk-art pieces in his collection.

Three untitled pieces by Ralph Griffin, ca. 1990, painted wood

34

William Anthony isn’t a self-taught artist like Tolson or a number of others whose work Williams started collecting in the 1970s and 1980s, but Anthony’s signature style plays on the figure-drawing mistakes most commonly made by people with neither artistic training nor talent. Williams’ friend and fellow writer Gilbert Sorrentino introduced him to Anthony’s work around the mid-1970s. Shortly thereafter Williams published Anthony’s first book Bible Stories (1978), a satirical version of the Old Testament distilled into fewer than thirty pages of hilariously bad drawings and brief texts, with an introduction by Sorrentino. Williams would eventually acquire nearly a dozen of Anthony’s drawings and paintings, and in 1988 he published the retrospective collection Bill Anthony’s Greatest Hits: Drawings 1963-1987, with an introduction by art historian and critic Robert Rosenblum. Among its diverse offerings, the latter volume features Anthony’s skewed renditions of famous artworks by Delacroix, Matisse, Munch, Picasso, Bacon, and other modernist masters.

35

Without narrowing the range of his visual interests, Williams immersed himself in contemporary southern folk art through the last quarter of the 20th century. During those years he added to his collection works by some three dozen self-taught artists from his native region, namely Leroy Almon, Z.B. Armstrong, Eddie Arning, Minnie Black, Georgia Blizzard, Vernon Burwell, Raymond Coins, Ronald Cooper, Granny Donaldson, Sam Doyle, Howard Finster, Harold Garrison, Russell Gillespie, Denzil Goodpaster, Ralph Griffin, Dilmus Hall, James Harold Jennings, Clyde Jones, Jacob Kass, O.W. ‘Pappy’ Kitchens, Eddie Owens Martin (aka St. EOM), Carl McKenzie, Clete Meaders, Ruben A. Miller, ‘Sister’ Gertrude Morgan, J.B. Murray, Leroy Person, W.C. Rice, Juanita Rogers, Nellie Mae Rowe, Mary T. Smith, William Cook Stanton (aka ‘Brother Rat’), Jimmy Lee Sudduth, Mose Tolliver, Bill Traylor, Fred Webster, and a few others.

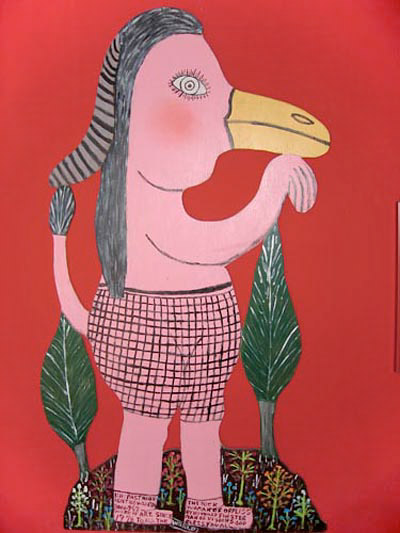

Duck Woman of Orphiss: Harold Finster, ca. 1984, enamel on plywood cutout

36

Williams sought out most of these artists where they lived, not only so he could buy art from them, but also to get to know them with the aim of eventually writing about them and their work. A number of the essays, poems, and photographs that emerged from these encounters are collected in Walks to the Paradise Garden, an illustrated manuscript that unfortunately remains unpublished. Williams envisions his own core contributions augmented with additional photographs that Guy Mendes and Roger Manley made of some of the artists and their work, often while traveling with Williams. Williams has declared the book too expensive an undertaking for the Jargon Society and none of the other publishers who has seen it has been willing to take it on, despite the widespread popular interest in folk and ‘outsider’ art in the years since he became a pioneering enthusiast and champion of such work. [9]

37

Williams did much of his field work for Walks to the Paradise Garden between 1984 and 1987, as part of a larger, Jargon-sponsored endeavor called the Southern Visionary Folk Art Project, of which I was director for its three-year duration. In addition to researching and documenting the art of self-taught artists in the region, Williams and I also pursued his idea of establishing a museum devoted to such work, a notion that proved to be overly ambitious and was finally abandoned. Much of my own effort under the project’s auspices centered on two artists from Georgia, Eddie Owens Martin and Howard Finster. As we wrapped up work on the project, Jargon published my book on Martin (St. EOM in the Land of Pasaquan, 1987), profusely illustrated with photographs by Williams, Manley, and Mendes. The similarly well-illustrated, as-told-to autobiography I co-wrote with Finster was eventually published by Abbeville Press (Howard Finster, Stranger from Another World, 1989). Williams’ deep interest in this variously named, non-academic art is reflected in only one other Jargon publication, Paul Metcalf’s Araminta and the Coyotes (1991), whose cover image reproduces a Mary T. Smith painting. [10]

Vernon Burwell: Black and white cat, ca. 1984, painted concrete

38

The zeal with which Williams pursued his interest in folk art didn’t overwhelm his other visual-art interests. The early 1980s also saw the Jargon Society publish a couple of photography books (The Photographs of Lyle Bongé, 1982; and John Menapace’s Letter in a Klein Bottle, 1984). Williams arranged for the posthumous reproduction of several late Philip Guston drawings as ‘illustrations’ for Jargon’s 1988 publication of Joel Oppenheimer’s Names & Local Habitations (Selected Earlier Poems, 1951-1972). More recently Jargon published two books of landscape photography — Elizabeth Matheson’s Blithe Air: Photographs from England, Wales, and Ireland (1995) and a book devoted to Mark Steinmetz’s photographs of Tuscan Trees. The latter volume appeared in 2001, the fiftieth-anniversary year of Williams’ first Jargon publication.

39

With his birthday on March 8, 2008 — one day after this exhibition opens at its premiere venue — Williams will mark the beginning of his eightieth year. As befits his advancing age, he has gradually slowed the pace of his activities, including his publishing endeavors. He still has a few other writers’ manuscripts he would like to publish under the Jargon imprint, should funds become available, but his energy for pursuing financial support isn’t what it used to be, and his ability to do so has been curtailed by health problems.

40

His most persistently troubling ailment is chronic numbness and pain in his feet, a condition medically diagnosed as neuropathy, which has limited his mobility since 1999 and put an end to the peripatetic travels that formerly drove his efforts. Nowadays he’s a virtual hill hermit, rarely leaving his house. But Skywinding Farm makes for a comfortable and esthetically satisfying hermitage, furnished with the antiques his parents collected and otherwise largely decorated with his own art collection. If you get tired of looking at the art, you can always gaze out the big west-facing windows at the spectacular, sweeping view of northeast Georgia and the Nantahala Mountains. For company and all manner of invaluable assistance (not least of all culinary), Tom Meyer, Williams’ poet partner of nearly forty years remains in residence, evidently in first-rate health and top literary form at a very young-looking sixty-one. Additional company includes H.B. (Hale-Bopp) Kitty, fabulous orange-tabby feline-in-residence, and frequent visitors, mostly longtime friends and cultural associates. [11]

41

Williams has accumulated plenty of laurels to rest on, and he certainly deserves a respite. Indeed, the Loco Locodaedalist appears to be reliably in situ at Skywinding until further notice. [12] His life has settled into a fairly steady daily routine that involves waking up around 9 a.m. and spending most of every day in a comfortable chair in the cathedral-ceilinged living room with a good view from one of those west-facing windows. Thus installed, he reads newspapers (The New York Times and USA Today), mystery novels, biographies, and some of his mail; sometimes takes phone calls; writes notes and maybe the occasional poem on a yellow legal pad; and watches daily news reports and selected sports events on the nearby TV. He augments the healthy daily diet that Tom Meyer provides with a mid-day vodka martini, a glass of single-malt Scotch whiskey before dinner and usually another one afterward, along with a cigar enjoyed while listening to recorded music — invariably classical or jazz — until going to bed around 10 p.m.

42

Living well — said to be the best revenge — has for Williams always entailed living with art. And what says more about a man than the art he lives with?

43

(BTW: Williams knows its bad luck to kill a snake. Especially with art, subject to damage and to be handled with care.)

44

— Winston-Salem, December 2007; revisited January 2009

[1] Some of the more informative and insightful writings on Williams’ writing and publishing career include Joel Oppenheimer, ‘On Poetic Injustice’, Village Voice, April 9, 1979, p. 8; Kenneth Irby, ‘America’s Largest Open-Air Museum’, Parnassus, 1980; John Russell, ‘Jonathan Williams’, New York Times Book Review, Feb. 13, 1983; Jim Marks, ‘A Jargon of Their Own Making: Williams and Meyer Have a Way with Words’, The Advocate, Nov. 24, 1987; Susan Tamulevich, ‘Black Mountain Bard’, July 1990, pp. 36-39; Jim Cory, ‘High Art & Low Life: an interview with Jonathan Williams’, James White Review, Fall 1993, pp. 1-4; Tom Patterson, ‘O For a Muse of Fire: Jonathan Williams and the Iconoclasm of The Jargon Society’, afterimage, March-April 1996, pp. 8-12; Jeffery Beam, ‘A Snowflake Orchard and What I Found There: an Informal History of The Jargon Society’, North Carolina Literary Review, vol. 6, 1997, pp. 16-27; Jeffery Beam, ‘Tales of a Jargonaut: an interview with Jonathan Williams’, Rain Taxi online edition, Spring 2003. [Also see the Jargon web site at http://jargonbooks.com/ for an unabridged version.] The most recent exhibition centering on The Jargon Society’s publications (and including a limited selection of related art from his collection) was ‘Jonathan Williams and Friends’, at the Asheville Art Museum, Asheville, N.C., Sept. 3, 2004-Jan. 9, 2005, which was accompanied by an illustrated, six-panel brochure including essays by Williams and the museum’s executive director Pamela L. Myers.

[2] Jargon-published artworks by Ruff, Rice, Elsworth, Laubies and Oscar, as well as a number of other artists’ images reproduced in later Jargon publications, have either been sold by Williams or are included in the Jargon Archive, housed in the Poetry/Rare Books Collection at the State University of New York at Buffalo. See the collection’s catalog Jargon at forty, 1951-1991.

[3] Selected photographs by Williams have been collected in two volumes, Portrait Photographs (Gnomon Press, 1979) and A Palpable Elysium: Portraits of Genius and Solitude (David R. Godine, 2002).

[4] Black Mountain College was a small, progressive, arts-centered institution that existed near Black Mountain, North Carolina, for twenty-five years beginning in 1932. See Martin Duberman, Black Mountain: An Exploration in Community (New York: W.W. Norton, 1972, 1993); Mary Emma Harris, The Arts at Black Mountain College (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1987); Vincent Katz, ed., Black Mountain College: Experiment in Art (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2002); and Michael Rumaker, Black Mountain Days (Asheville: Black Mountain Press, 2003).

[5] Editor Jeffery Beam notes: Jonathan’s crossings of the continent with books in his trunk are legendary now – sometimes described as being in a Volkswagen, sometimes in a station wagon. I queried Thomas Meyer as to the facts. His email reply on February 7, 2009: ‘Jonathan traversed this holy continent on several occasions. Coast to coast eight times? Twenty? Can’t remember how many, the number is mentioned by him somewhere. The first forays (readings/ preachings/ sellings) were made in a Studebaker station wagon handed down to him by T. Ben [Jonathan’s father, ed.]. Vague sense that there could’ve been more than one of these cast off family vehicles — always Skywinding station wagons. Then there came the VW sedan, gray and dubbed The Shadow, if memory serves. Early 60s. Succeeded by various VWs. The last full driven circuit (Skywinding to LA/ SF/ Seattle and back via NM/ TX et cetera) off the top of my head was December to January 1978 - 1979. By 1980 it was airplanes some or all of the various ways. You know, Jonathan had never flown, and was afraid to, until 1971. The virgin flight was in Don Anderson’s personal Lear Jet. Nice introduction to sky ways’.

[6] Blues & Roots / Rue & Bluets: A Garland for the Appalachians, Grossman, 1971.

[7] Much of Williams’ correspondence with Davenport was published in A Garden Carried in a Pocket: Guy Davenport / Jonathan Williams, Correspondence 1964-1968, Thomas Meyer, ed., Haverford: Green Shade, 2004.

[8] In A Palpable Elysium: Portraits of Genius and Solitude, pp. 44-45, Williams writes of his visit with Schmidt alongside a reproduction of one of his photographs, showing a detail from the Silver Forest.

[9] For detailed information on many of the self-taught artists whose works Williams has collected, see Jane Livingston and John Beardsley, Black Folk Art in America, 1930-1980, Corcoran Gallery of Art/University of Mississippi Press, 1982; Roger Manley, Signs and Wonders: Outsider Art Inside North Carolina, North Carolina Museum of Art, 1989; Alice Rae Yelen, Passionate Visions of the American South: Self-Taught Artists from 1940 to the Present, New Orleans Museum of Art, 1993; Paul Arnett and William Arnett, eds., Souls Grown Deep: African American Vernacular Art in the South, Vol. I & II, Tinwood Books, 2000, 2001; and Gerard C. Wertkin, ed., The Encyclopedia of American Folk Art, Routledge, 2004.

[10] For more information on The Jargon Society’s Southern Visionary Folk Art Project see Tom Patterson and Roger Manley, Southern Visionary Folk Artists, a twelve-panel foldout brochure published by The Jargon Society, 1985; see also Let It Shine: Self-Taught Art from the Marshall T. Hahn Collection, High Museum of Art, 2001, pp. 54-55.

[11] About six months after Williams’ death, H.B. Kitty went missing, never to return. Several domesticated cats in and around Scaly Mountain were killed by coyotes around that time, and H.B. is likely to have been among the victims.

[12] The reference is to Williams’ book The Loco Logodaedalist in Situ (Cape Golliard/Grossman, 1971).

Tom Patterson is an independent writer, art critic, and curator who lives in Winston-Salem, North Carolina.