| Jacket 38 — Late 2009 | Jacket 38 Contents page | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 18 printed pages long.

It is copyright © Natalie Knight and Jacket magazine 2009. See our [»»] Copyright notice.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/38/r-toscano-rb-knight.shtml

Rodrigo Toscano

Collapsible Poetics Theater

reviewed by

Natalie Knight

Fence Books 2008 96 p9 $19.00 Paper, isbn 978-1-934200-18-6

Laura Elrick, “Humana Ante Oculos,”

Alexandria, Virginia

1

Check it out: not a minute to yourself, not a hang-nail’s worth of deliberation to relieve throughout your high capitalist day — everybody up to their necks with poems, and still, your poem — cannot be tested — any further!? (Toscano, Correspondence)

2

Testing poems, testing readership, reading ability, sense and nonsense — these trials have been central to Rodrigo Toscano’s work since his earliest texts. Polyvocality consistently asks for more than the reader or author can provide. In Platform and To Leveling Swerve, Toscano maintains a polyvocality that works; that is, one that’s legible, playfully unpredictable, but predictably text-based so that the reader can return again and again to work it out. In Collapsible Poetics Theater polyvocality loses one more hinge — accents are spoken by those within and without them, words sit on players’ tongues that “arrive” from far-off cultures (or cultures close to home but on the other side of the tracks).

Section 3

What can a poem do that a body can’t? Or, what can a poem do with a body? What can a poem do with a body unleashed in an altered, staged setting that releases, or refuses, charactered and personalized representation — in a poetics theater, that is? These are the questions that compel Toscano from text-based poems to polyvocalism, “theater” pieces, and body movement poems, the three major genres of Collapsible Poetics Theater (so far). Such are the creative imperatives.

4

What are the means of production? What energies and knowledges, creative and otherwise, contribute to the formation of Collapsible Poetics Theater? Toscano’s bilingualism is a clear starting point, and a mode of translation all its own. He writes for a readership spanning the Greater Americas, as Toscano coins it, “from Point Barrow, Alaska to Punta Arenas, Chile,” and his poems received most often by an English-language readership include French, German, Latin, contemporary dialects and subdialects, academic-speak, single-syllable chat room sentence strings, urban slang, techno terms, among others (Toscano, Correspondence). His poetry is therefore translingual in his inclusive use of many linguistic transgressions and switches. Platform and To Leveling Swerve incorporate all of these linguistic modes, and Platform verges on polyvocality, tilts towards it, anticipating the full-on move to multiple embodied voices arriving in Collapsible Poetics Theater. Those vocabs that accompany social and political activism (transcribed meeting minutes, manifestos, speeches, legislative works, etc) don’t comfortably fit inside poetic structures, and yet traces of these forms emerge throughout Toscano’s latest works. The navigation between socio-political concerns and the aesthetics of language is a constant conflicting site from which much of the lasting creative import derives. And finally, on top of the multilayered productive means established through the constant casting and recasting of poetic forays, Collapsible Poetics Theater challenges the boundaries of written text in an entirely other venue by performing “texts” as body movement poems that often include more gestures between bodies than meaning-making through verbal exchange. CPT represents Toscano’s “full install” (“Unzips” 3).

5

Toscano’s language-play stands out among contemporary American poets; skirting the brink before collapse into what appears to be pure sound (to a monolingual, monocultural ear), retaining transferable political and social critique that’s embedded, underground, autonomous in its resistance to coercive commentary. The “uneconomical effort of language learning,” as Doris Sommer puts it in Bilingual Aesthetics, opens “detours around decayed or clogged pathways of a first language” so that the arrival at a poetic combination is never a rearticulation of thoughts or poems past, but its own unique, fully installed parameter (xix). “Bilingual gamesmanship” lends itself to “a predisposition towards feeling funny, or on edge, about language, the way that artists, activists, and philosophers are on edge about familiar or conventional uses” (xii). This is gamesmanship accessible to any wordsmith who happens to stand among multiple language centers, within border zones; there’s a democracy to code-switching language games that provides wholly innovative routes into a poetics characterized by athletic maneuvers around multiple meanings. Code switching is, in short, nothing new — such a celebration of it in poetic terms, however, is perhaps characteristic of much of the lasting art in the latter half of the 20th century, and into the 21st. As Sommer reminds us:

6

It’s not that diglosia vanished from literature altogether after the Middle Ages; anyone can name occasional experiments with the more-than-one language. Nor is immigration or mass displacement a new phenomenon. What is new are the great numbers, the visibility, and the postmodern moment that unravels the dangerous identity between (administrative) state and (cultural) nation to recover the wiggle room between the terms. Now, again, multilingual experiences are a significant feature of literary art. The creativity is de facto. Do we take seriously enough — as teachers and citizens — the responsibility to render the creativity visible and audible? (27)

7

That unraveling of the administrative state and cultural nation, that discovery of “the wiggle room between the terms” resonates deeply in Toscano’s poetics. He seems to ask, Do we take seriously enough — as poets, as “activists within culture” — the responsibility to render the social in terms so energetically charged to push thought, language, and down the road, a body or two forward? (“Unzips” 3). What are the limits of the poem, in this context?

8

Mark Nowak writes about the selection of Toscano’s work for the 2007 National Poetry Series that “left-labor and social movement verse theater received one of its first poetry-world awards… ” (“Fences”). It isn’t surprising, as Nowak rhetorically asks, that Collapsible Poetics Theater “intricately addresses the laboring body in the spaces (environments, geographies) where language intends to but doesn’t always cohere — where it slips, breathes in something it wasn’t supposed to, falls and gets back up and attempts to coalesce [yet] again.” Theater has developed into a way to act out Sommer’s realization that “for each language or foreign inflection there was another persona… [eventually] I understood that real authenticity means being more than one” (xxii). If a poetics truly tests the poem, as Toscano’s claims to do in CPT, and does so with channels open like millions of bilingual residents, “alien” and “natural” alike, it seems right to anticipate a testing of the body as well — that site from which individual contradictions and experiences of stepping outside “oneself” into “another persona” erupt, a combustible site of human potential.

9

This testing of the body occurs, then, at the center of Collapsible Poetics Theater. Body can be here, and be contradicted here, along with language and politics, in a rough-hewn method of assembling and reassembling poetics theater players. And, “roughing it, let’s not forget, is a reliable… recipe for pleasure by way of discomfort” (Sommer 30).

10

We are not free. And the sky can still fall on our heads. And the theater has been created to teach us that first of all.

— Antonin Artaud (79)

11

Collapsible Poetics Theater is a translation of a poetics into a poetics theater, a space specific and its own. The “theater” third of CPT has as its inspiration, in large part, the radical theatres of the past half-century, like The Open Theatre, The Living Theatre, El Teatro Campesino, The Bread & Puppet Theatre, and many others. Toscano’s work is both highly distinct from and intently aware of these radical predecessors. Arthur Sainer writes about the changing American theatre (particularly American, though some ensembles went on, and came from, various international sites) in the late 1950s and early 60s as “a double loosening, first involving the immobility of character in situation… and then, more radically still, involving the attitude of performer offering self rather than character. There was no precedent in American theatre for this loosening” (9-10). Characters in the traditional theatre “waited for their next fix;” characters were “determined by fate, at times in the grip of the unconscious, at times in the grip of Higher Powers” (11). The furthest theatre pushed its Modernist limits, Sainer notes, is Beckett’s Waiting for Godot. In that minimalist capturing of eternal waiting, “Beckett’s people are perennially involved in a Cartesian attempt to analyze their condition, to understand” (33). Characters move through a deserted landscape nearly unknown to themselves, unable to speak meaningfully and certainly in doubt of even the possibility of meaning presented in speech.

12

The acts [of brushing teeth, prayers, physical exercises in Act Without Words II] are referral points, landmarks in a desert. They are stabilizers, reassurances, operating much as the crutch of closely and regularly positioned lampposts might operate for a cripple… . [The characters] can’t change the condition of things, they promise what they can’t deliver. One is always expectant — one is always disappointed. (33)

13

The radical theater of the 1960s took up where Godot left off, doing away with the determinative use of character embodied by the actor, paralleling Beckett’s incessant critique of Western society’s fetters; always incessantly critiquing, unable to act something, anything, other. The radical theatre found immediate value in alterity, and with it moved with the current or moved the current beyond high modern and into postmodern concerns.

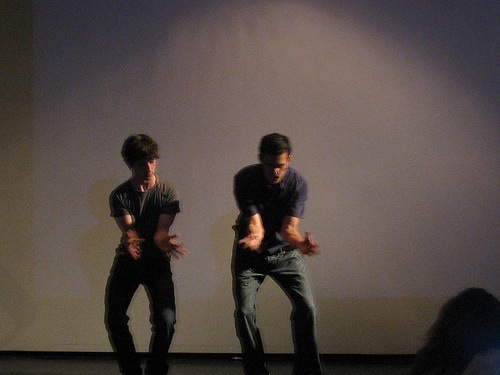

14

How is CPT in relation to the radical post-1960s theatre? CPT and The Living Theatre take many cues from Artaud, Brecht, and Grotowski, including re-conceiving the very space of theatre. The Living Theatre’s critical stance against the traditional theatre space in favor of the street, the makeshift stage, or the living room is in line with CPT’s “collapsible” quality, springing up in Contact Zones across the country from a suitcase, a few printed poem-scripts, and a 48-72 hour clock for rehearsal (and sometimes the first time players have met Toscano or each other). Collapsible speaks to the political, and then literal, organization of CPT; an organization that assumes a cell-like ability to reconvene in various locations using resources at hand, and to fold back into the poetic-political locale. It’s the ability to reorganize with new players and old players, new and old locations. After a performance, CPT’s players submerge back into the soil, and if all goes energetically, feed into the developing poetic space for new growth.

15

CPT acknowledges (in an extensive page fronting the entire Collapsible Poetics Theater book, listing no less than 89 individuals, the vast majority of whom are poets) the impossibility of its existence without the various Contact Zones, but the project isn’t acephalous. Toscano’s the writer and artistic director, that’s always outright. The poetics in this poetics theater, like the poetics in any of our potential theaters, is his artistic development resulting from years of writing and engaging with the world at large. He writes,

16

You might ask, ‘ok, why can’t the ‘poetics’ element of PT be made by a group of people (more than just RT)?’… Who is in the most favorable position to translate its fundament? At least the first few hundred strokes?… You see, if one’s ‘poetics’ is already ‘numerous’ and ‘multiple’ to begin with, who has the best chance at consolidating it, filtering it, but most of all, translating it into new formats? (Toscano, Correspondence)

17

Unlike ensemble development in other theatre groups, or poets theater in which poets decide on collaboration with some assumption that it will necessarily result in a more egalitarian product, loosened from the politics of authorship, CPT develops consciously from poetic texts first, followed by the multiple and always-varied enacting and doings of the texts in each performance site. The challenge in the process of a more typical poets theater collaboration is to resist forfeiting one’s developed and developing sense of agency, the ground one clears in one’s practice of poetic engagement. The challenge in the process of Toscano’s poetics theater is to remain authorial and yet attempt to diffuse that authority through self-reflexive sleight-of-hand.

18

So as it stands, CPT exists somewhere between guerilla and autocratic; guerilla because in their sleeper cells dotting the North American cities and bergs, guerilla players can be activated at nearly a moment’s notice. Toscano is, at the end of the day, the autocratic coordinator but doesn’t dismiss the possibility of infiltration by another poetics (or multiple others): “it can, provided the participants have each developed a poetics that is recognizable (in its political valence most of all), so that a conjoining of poetics is a carefully honed negotiation and not a watering down of each other” (Toscano, Correspondence). It’s this careful negotiation between different valences that feeds the political engagement of Toscano’s poetics in his written work. And so by engaging with numerous players the coordination of a piece must draw from the strengths and abilities of those participants in order to be the real deal, a heaving, precarious embodiment and entity-formation that provides reflection on the world and posits a space other than the contemporary zone.

19

Toscano circumnavigates the question, “Should CPT operate as an ensemble? If not, then as what?” with his response, “To each according to her/his needs and abilities. The famous quote by Marx” (Toscano, Correspondence). By which I take him to mean a built-in mode for dealing with and responding to fluctuations of the personal, the group, and the poetic, so that each (player, poem) according to his/her/its needs and abilities (to play, construct, be acted in poetics theater) communicates always and acts always, never consolidated into the “ensemble” model that solidifies while it intends to hone for greater collaboration.

20

Collapsible Poetics Theater differs from The Living Theatre’s premises in its interpretation of Grotowski’s definition of theater, characterized firstly by the division between actors and spectators. “There had to be spectators for there to be theatre. Now, as to what kind of spectatorship was to be sought — that was an open question. In other words, if one goes into a classroom and gets everyone involved, including the teacher and oneself, into an activity (or several, all at once, or even in turns), where everyone is an actor — then that’s not theatre” (Toscano, Correspondence). “I always found this very funny,” Toscano writes. Theatre for Grotowski is above all an artificial construction of a space necessarily removed from our living surroundings, a space where actors act other than the composite acting/spectating individuals of the “real” world. The space can be a closet or the street, pedestrian and utilitarian in the day, but it’s transformed into its other (other than pedestrian and utilitarian) by harnessing the space for theatre. CPT accepts this artificiality, if only to work on breeching it, whereas The Living Theatre sought to return theatre to the streets entirely. The Living Theatre wanted a “performer [who is able] to watch the performance; he becomes a third party, a bridge between audience and character, an intelligence which breaks in on the illusion of the continuous action of the drama… . The attitude of performer as self causes the responsibility for the world to be thrown back onto the audience, to be shared with the performer” (11). This desire for “the responsibility of the world” “thrown back onto the audience” reflects the progression of The Living Theatre literally into the streets of Brazil, where theatre was made in village schools, “written” through the collaboration of schoolchildren who, for example, volunteered dreams about their mothers for the piece The Mothers Day Play. The Living Theatre saw theatre as a radical potential to motivate workers, students, and impoverished communities into action, and manipulated form to radical degrees in attempt to realize this project.

21

Though Toscano has a background in labor organizing through jobs as union organizer, social worker, and his current position at The Labor Institute in Manhattan, his activist politics don’t dominate the aesthetic space of CPT. Or, rather, “activist politics” can’t get off the ground without running into language, always haggling, bartering, and opposing one political agenda to another as it travels into new neighborhoods, cities, coasts. All this is allowed and encouraged to contradict; the more potentially conflicting materials, the more events can occur in Toscano’s highly tuned poetics. The Contact Zone is never entirely collapsed and spectators are never in total identification with the players. Alterity runs rampant, unleashed.

22

Alterity read into Grotowski’s delineation of theatre’s requirements means that the artifice of settling on some bodies as actors (players is Toscano’s term) and some bodies as spectators allows us to consider the fluctuating, multiple roles we each play in our various social positions. If theatre does anything at all, it relieves us, for just some moments, of the weight of multiplicity by projecting split-selved beings onto the stage in order to (possibly) reveal something about the nature of our duplicitousness.

23

In order to be at all self-reflexive about the form of theatre, Toscano (like his Radical Theatre predecessors) must necessarily breach this split-selved (player-spectator) division. Method, or Labs and exercises, negotiated by players and by Toscano as artistic director and writer, operate in CPT to find those tactics that can confuse the binary of spectator-player. Skirting the ditches of “self” and “other” through textual and bodied techniques proves to be a vital part of Toscano’s poetics.

24

A principal difference worth impressing between the Radical Theatre movement and Toscano’s poetics theater is its, of course, poetics theater. Though the Living Theatre began with performances of texts by Gertrude Stein, T.S. Eliot, Brecht, Cocteau and others, the group’s directors Judith Malina and Julian Beck quickly moved away from text-based performance in favor of developing work in Laboratory, often over several months or even years. Forming a piece was a constant collaboration between actors, sometimes with one or two writers sitting in and providing partial texts that would then be tested and revised during Lab. In The New Radical Theatre Notebook, Arthur Sainer documents accounts of the precarious relationship between writers and performers in The Living Theatre and its theatrical offshoots, where the legacy of the primacy of the text wasn’t easily overcome.

25

In contrast, Toscano works explicitly from poetic texts. Poetics theater, for him, is a translation of ideas, thoughts, speculations, poetries fomented in poems that make themselves, or simply are in their peculiar making, translatable into Body Movement Poems, Masques, Anti-Masques, Poetics Dialogues, Radio Poetics Plays, and so on — all forms that foreground textuality and retain textuality even with its problematic implications for theatre. CPT exists always precariously; intertextual, interlanguage, in space and among different spaces, varying speech patterns with cultural and linguistic resonances not lost on the players or speculators. Toscano is, after all, a poet. Reading Collapsible Poetics Theater isn’t completely satisfying; and watching a CPT performance may leave some performance studies enthusiasts wanting more embodiment with more self. The tightrope walk between these radically different impulses is Collapsible Poetics Theater, which, though it may collapse into its small covers at the end of a performance, will not collapse into an easily digestible rearticulation on one side of the text/body fence. This is its enduring contradiction, and as contradictions spur us on and refuse flattening into simple meanings, CPT will continue to open spaces of alterity by refusing to evacuate multiple personae.

26

Still, given the forthcoming critical riffs [1] on poets’ theater as a dynamic element of poetry communities, why is Collapsible Poetics Theater a “poetics theater” and not “poets’ theater”? What of Gertrude Stein’s 1920s Paris salon, what of Geography and Plays? Or the brilliant history of impromptu, quick set-up North American poets theater in the past 30 years, or Small Press Distribution’s own yearly stagings of theatrical hilarities and poetic transgressions? Let’s look to Artaud:

27

For me the theater is identical with its possibilities for realization when the most extreme poetics results are derived from them; the possibilities for realization in the theater relate entirely to the mise en scene considered as a language in space and in movement. To derive, then, the most extreme poetics results from the means of realization is to make a metaphysics of them… . (45)

28

Not to get lost in the metaphysical brambles for too long, Toscano renders this notion always on edge with the socio-political: “The mission is to capture instabilities in the social just long enough to have others ‘sense’ it; and also to explode stabilities, but still manage to render ‘visible’ (in the mind — of a higher ape) the multiple motions of that Big Rip” (Toscano, Correspondence). Mediating the deterministic histories within the politically motivated language in many pieces of CPT with the hopeful presence of bodies on stage is itself a constant site of translation. A constant negotiation of text and body is among the first concerns of CPT, unlike many (though certainly not all) poets theaters. Let’s keep to Artaud:

29

… the question of the theater ought to arouse general attention, the implication being that theater, through its physical aspect, since it requires expression in space (the only real expression, in fact), allows the magical means of art and speech to be exercised organically and altogether, like renewed exorcisms. The upshot of all this is that theater will not be given its specific powers of action until it is given its language. That is to say: instead of continuing to rely upon texts considered definitive and sacred, it is essential to put an end to the subjugation of the theater to the text, and to recover the notion of a kind of unique language half-way between gesture and thought. (30)

30

Still applicable, even after the 20th century loosening of theatre from text, is Artaud’s call for a “language half-way between gesture and thought” that can, in Toscano’s verbiage, “render visible the multiple motions of that Big Rip.” A poetics theater finds that “magical” art and speech “organically” together, though never together in the sense of reconciliation. With a few dozen (or hundred) bursting socio-political quips and commentaries that rupture as soon as they fill with air, the resulting performance wobbles between air-tight and leaking, dancing and struck, working and slacking — a momentum that refuses to swoon while it’s standing, and dissipates as soon as it ceases into the mere handful of props and pages that began the whole thing. Whereas many poets theaters assume two (or more) poets coming together for the express purpose of collaboration, and to some degree feed off and revolve around this collaboration, poetics theater feeds from the poetic text, hungry for more. Bodies are bodies, poets are poets, the project inconceivable without them. But the text, the text, in direct shake-down with the scene, the scene, is where Toscano finds “play” (whether rough, light & easy, pokey, or even a deadpan denial of “play”).

31

The action in this text-scene then, the Contact Zone, goes past “energy” towards a belief-form: it isn’t the will that’s engaged but a socially sprung entity that wills, something taking place beyond theatre that becomes “theatre” only because of its leaving it, striking at an atavistic nerve from (neo-Brechtian) distance. The player’s expression results from piercing through the design of a theater space into that which rears energetically beyond and around language:

Rachel Schramm, “Pig Angels of the Americlypse,” Miami, Ohio

32

“Pig Angels of the Americlypse” is not completely unlike Sainer’s account of the OM-Theatre Workshop performance in 1968, Om, a sharing service, during which spectators were invited to Arlington St. Church in Boston, MA while the performers slithered behind partitions and finally out among pews, eyes closed and hands reaching out. These hands occasionally met a spectator, and sometimes hands were held, or even kissed. “The entire impulse of the experimental service was toward a psychophysical contact between performer and spectator. The extension of the performer’s fingers, the act of reaching out to touch, became one of the dominant motifs… . The dynamics of the performer unleashes those of the spectator. Through an act of will, the spectator coheres the action or breaks (rejects) it” (36). Creating the divide between spectator and player allows the possibility of enfolding that divide back into the quilt-like experience of Being. Setting up in order to pierce through the theatre’s most fundamental artifice shocks both player and spectator alike, so that Schramm’s registered shock during “Pig Angels of the Americlypse” transfers off and out of the staged area to the visceral registers of the audience. Toscano’s poetics breeches something more than the divide between spectator and player, more than the division between language and emotion. Players are not selves in CPT performances; they are, in Toscano’s words, “entities,” neither human nor inhuman, neither expressive actor nor passive audience. In this sense they can be that “performer [who is able] to watch the performance,” that “third party” who is “a bridge between audience and character, an intelligence which breaks in on the illusion of the continuous action of the drama” that, at times, The Living Theatre sought in performing as selves rather than characters (Sainer 11). Schramm’s visage shocks us, striking our atavistic nerves and compelling us towards an acknowledgment of elsewhere, beyond stage and auditorium altogether.

33

Toscano wants more than words, and some elsewhere than feelings, and seems to sense Artaud’s estimation “that the highest possible idea of the theater is one that reconciles us philosophically with Becoming, suggesting to us through all sorts of objective situations the furtive idea of the passage and transmutation of ideas into things, much more than the transformation and stumbling of feelings into words” (109). If poetry is “anarchic” like Artaud claims, it is because “it brings into play all the relationships of object to object and of form to signification,” loosening the stage of meaning-making by inhabiting some space not too distant from an unutterability behind language (43). In Schramm’s posture we can nearly see that “Double, behind the Warrior,” who “bristl[es] from the formidable cosmic tempest… and who, roused by the repercussion of turmoil, moves unaware in the midst of spells of which [s]he has understood nothing” (67).

34

The first spectacle of the Theater of Cruelty will be entitled: THE CONQUEST OF MEXICO

— Antonin Artaud, 1938 (126)

Bold conception that of Sub-Commandante’s — why not wholesale it?

— Rodrigo Toscano, 2008 (CPT 7)

35

To each according to her/his needs and abilities. To go back to Toscano’s engagement with Marx. Toscano notes that, “Some needs change, some don’t; some abilities change, some don’t that much; often needs turn into other things, including abilities, and abilities turn into needs, strangely enough.” The “projective (note: not ‘real’) politics of the CPT” is this “making way for the growth of human potential” (Toscano, Correspondence). Trickled down, or up, the relationship between the legacy of colonialization in the Americas and human potential, what might rise up, forms the Modernist-era “first spectacle” for Artaud’s new Theatre. Never a moment late on the further complicated context of our times, Toscano remarks that, sure, it was a “Bold conception that of Sub-Commandante’s,” and so, “ — why not wholesale it?” (CPT 7). Toscano hails, “¡Movimiento a la constucción de bombas poeticas efectivas para explotar la dirección general de Bechtel!” and never a moment late on real-world subversion, answers, “Where do I sign up for a Spanish class?” (CPT 22).

36

To each according to his/her needs and abilities. How can a poetics be theorized for a theater that is at once abstract, played by entities rather than actors, intent on (inconsistently) confusing the player-spectator divide while the textual content is often (and more than) a list of international political radicals and American democracy’s grandfathers alike? CPT, if you can manage to unread the constant language games that indeed construct as much meaning as anything else, sometimes reads like the notebook of an historically savvy activist whose political agency has been worn to puns. Because the real agency is in the theatrics. Toscano’s poetics isn’t so much a poetics, like a theoretical container for his poetries to whisper from, but an erotics, or poetics of erotics, that insists on embodied transgressions in a cleverly self-reflexive stage that explores the potential of an entity’s ability to both lack and exceed humanity. The agency is in the exchange, conscious or un-. “Direct example, after a performance of “Spine” (with two others) in Auburn, NY, I’m kind of a drone, and the players are light on their feet for days after, and open to new things in their own work (as by their reporting that). What was my need became their abilities, what was their ability has now become my need — a new one. That’s the erotics of it!” (Toscano, Correspondence)

37

“Beast hath made us, beast hath not” reads the epigraph to “Truax Inimical” (CPT 1). Getting at something guttural, that which lacks or exceeds humanness, is a crucial component of the erotics of Collapsible Poetics Theater.

Tom Orange, “Spine,” Alexandria, Virginia

Jason Conger and Sophie Gordon, “Spine,” Olympia, Washington |

Gregory Stuart, “Humana Ante Oculos,” Alexandria, Virginia

Rodrigo Toscano and Tom Orange, “Spine,” Olympia, Washington |

38

What’s captured in these photographs of CPT performances are gestures and expressions seemingly more-than-human; gestures freed, probably unconsciously and certainly only momentarily, to jest without expectation. “Bestiality and every trace of animality are reduced to their spare gesture: mutinous noises of the splitting earth, the sap of trees, animal yawns” (Artaud 66). Artaud’s Double haunts the entities in these CPT performances, seeping through the embodied beings of players, through the textual parameters of poetics, out into the Contact Zone like unfettered energy back to the source. What happens, erupts. What erupts, releases like a gift into the creative space of the performance. These players-turned-entities ask, if “life is pulse really,” “how’s it that we’re singular and one-at-a-time?” (CPT 19). And charge, impulsively, “Be a real human!” (CPT 110). CPT doesn’t answer these prompts; they’re unanswerable. But the space provides the opportunity for spectators to respond and recontextualize the poetic-political actions of CPT, thereby participating in an erotic poetics that requires, foremost, participants, and calls for the maximization of human potential in any Contact Zone, in any country — to exchange abilities for needs and back again, sharing in the sparks of artistic fly-offs…. Here is the role of the spectator-turned-entity (if she hangs around long enough!, as I have, performing “Balm to Bilk” and “Truax Inimical” most recently in March 2009 in Albany, New York.)

39

CPT is affirmative, as Derrida suggests of Artaud’s Theater of Cruelty, its own peculiar kind of “reeducation of the organs” (Writing 293). If the productive space is a gift, as I read it (to spectators and performers alike), it resonates provocatively within the theoretical framing of Derrida’s highly specific notion of the gift. Because, importantly, though there are political imperatives and motives in Collapsible Poetics Theater, transcendence of social inequality, of social contamination, isn’t the implicit goal of this theater project. As Artaud pressed hard towards a reworking of the Western interpretation of theater, and by extension the Western philosophical tradition, CPT again relates to the Theater of Cruelty in its adamant rejection of the closure of traditional metaphysics. There’s no transcendence posited in Toscano’s poetics; and that’s not unhopeful, either!

40

Because, like the suspension of character in Toscano’s entities, “the gift is a peculiar and perverse kind of ground that undermines the movement of transcendence… registered as an interruption or suspension of presence” (Cheah 45). In those brilliant moments “on stage” (or simply in the space cleared by pushing aside plastic tables and chairs in an unoccupied storefront, as it may happen to be), when the player’s body is an entity source erupting from the mingling of words, gestures, and space, and spectators are jolted from all expectations, is there not a transference within the limits of the Contact Zone that, unknown in the moment, interrupts the smooth sequence of time with texture?

41

Resisting ready-made political coherence (though not an intra-articulation of ideological points per say) thus becomes a poetic imperative in both the text-based and body movement pieces. Counter-pushes, or counter- counter- counter-pushes, push against the elimination of active thinking within political ideologies that are always at-risk of solidifying in the way only ideologies can. Body movement poems insert asymmetry in the form of erotic politics into poetics. This is paralleled in text-based poems by inserting clashing vocabularies and political registers, or the word “Pyongyang” as he does in the Platform poem, “Poetics:”

42

Pyongyang, if you’ll please, STOP

appearing

in the poem

like this —

unannounced

(30)

43

A few lines down follows, “’We call it dead in the wa wa / don’ mean jacky bits’ // ’Pyongyang’.” An East Coast nasally tone refracts against the totally “foreign” Pyongyang — sound jangles here, in contention. The poem concludes, “you got the mic pomomomo // make a ho’ yourself // and Maggy // and us” (33). A poem that seems to nearly personify Pyongyang in a gathering of “the E.U.’s / formative / contradictions,” “Thatcher,” “Quetzalcoatl,” and “Tarragon” isn’t clear about who is that pomo representative — the narrator, the reader, or all of us born of “ideolophe fahtha’(s)” and “para-juridical muhtha’(s)” with our “This-side-of-the-Hudson / Psycho-Acoustics” (30). The author’s implicated just as the reader is; there’s no clear superior political stance. Which is not unlike Derrida’s gift: “a ground that also ungrounds” an outmoded metaphysical system that offers up transcendence as the only (fated) option (Cheah 45).

44

For, as Phenh Cheah writes,

45

The act of the gift also points to an irreducible instability within social and political formations, their constitutive openness, and mutability. As Derrida notes, the control of time by the dominant socioeconomic classes, especially the control of labor-time, is the most fundamental factor in political economy. But the fact that time is a gift and cannot be owned by anyone indicates the possibility of the disruption and refounding of hierarchy and social domination. (49)

46

And in Toscano’s words, “What might ‘reify’ social abuses more than a specific genre or expressive modality is a practice of sitting pretty, clutching some tried-and-true method of yore, effective though it was then, now turned to froth. So this endless being hunted by froth. It might behoove us (resolute word-workers) to better understand froth in multiple dimensions” (“Unzips” 4).

47

An erotic poetics is “leading to a radical rethinking of agency and justice,” as Cheah writes of Derrida’s formulations, because CPT continues, as I write, to reconfigure and counter its own development (Cheah 47). The piece “Protagonistic Forces,” for example, weaves video segments of CPT performances together with additional body movement footage in a nearly meta-narrative reflection on the poetics thus far. The project folds in on itself, consumes itself, risks devolving up to another performance.

48

Critically cyclic: “One must engage oneself in this thinking, commit oneself to it, give it tokens of faith, and with one’s person, risk entering into the destructive circle” (Given 28).

Lindsey Boldt, David Brazil, Maxwell Heller, Erika Staiti, Dennis Somera, “Cordoned,” San Francisco, CA

Lindsey Boldt, David Brazil, Maxwell Heller, Erika Staiti, Dennis Somera, “Cordoned,” San Francisco, CA

49

“How’s it that we’re four distinct entities here? / How’s it that we’re each four times more than the other?” (CPT 19). “The living being conserves in itself an activity of permanent individuation,” Gilbert Simondon responds (305). In other words, ‘I’ am neither this thing or that thing, never statistically this formed individual; instead, ‘I’ is always “aris[ing] on the heels of a separation” (Simondon 316).

50

All this has more than something to do with an erotic poetics. Erotics, in 2009, not only requires but foregrounds the agency of the body, and with it stands not simply as a technical (“conceptual”) observer — it stands inside and among the destructive economy of social relations. Erotic poetics doesn’t shy away from contaminations, slippage or the bounding limits of bodily action. As Derrida attempts to imagine an economy of being and perceiving time that continually renews even as our presence binds it with limits, a contemporary, socially committed poetics must admit itself to engagement with limits that bind, from the outset, a full transcendental philosophy. Agency is retained through constant renewal which requires mistaken, “collapsed and reassembled,” identities and speeches, not through pronounced allegiances and maintenance of singular positions (though at times Toscano seems to be consciously “twiddling” these registers as well) (Toscano, Correspondence).

51

It’s a capacity for being present within disruption. The “capacity beings possess of falling out of step with themselves”(Simondon 300) corresponds to the capacity we have to fall in-step with ourselves, and with another “one-quarter of one whole” or “one four hundred millionth [rough population of the United States and Mexico] of one whole” (CPT 19 and 25). If “the living being is a veritable theatre of individuation,” how would a theater portray it? (Simondon 205). Collapsible Poetics Theater approaches these questions not as a vanguard, but through the spectator’s aslant reception of the performances, so that perhaps what we derive from CPT and submerge into our own poetics theaters (whether of the mind, the page, a theater of translation, or spacialized like Toscano’s model) gestures towards the constant negotiations of being individual in the social, with multiple personae and yet primarily modulating only one anatomical body.

52

How best to enact this? In duplicities, in multiplicities, of course.

Maxwell Heller and Rodrigo Toscano, Cell 7 of “Protagonistic Forces,” Vancouver, British Columbia

53

As Doris Sommer reminded us earlier of “the uneconomical effort of language learning” and that “real authenticity means being more than one,” CPT engages in the uneconomical effort of embodiment through response and commitment: “It is a matter of responding faithfully but also as rigorously as possible…. Know still what giving wants to say, know how to give… know how the gift annuls itself, commit yourself even if commitment is the destruction of the gift by the gift, give economy its chance” (Given 30). Tracings left over from all of our poetics theaters might critically engage with the effort of embodiment, the crutch of an erotic poetics, by actively participating in language play that illicits tension in potentially infinite varieties. Theatre, or poetics theater, in its artifice, is a space to respond to conflicting ideological and person-making entities in a commitment to giving economy, of body, words, thoughts, its chance.

[1] The forthcoming Kenning Anthology of Poets Theater: 1945-1985 (Kenning Editions) edited by Kevin Killian and David Brazil includes poets theater pieces from a wide range of American avant-garde traditions: http://www.kenningeditions.com/

Artaud, Antonin. The Theater and Its Double. Trs. Mary Caroline Richards. New York: Grove Press, 1958.

Cheah, Phenh. “Obscure Gifts: On Jacques Derrida.” Differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies 16.3 (Sept 2005): 41-51.

Derrida, Jacques. Given Time: Counterfeit Money I. Trs. Peggy Kamuf. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992.

———. Writing and Difference. Trs. Alan Bass. New York: Routledge, 2001.

Nowak, Mark. “Fences, Workers’ Theatre, & the CPT(s).” Online at http://poetryfoundation.org/ harriet/2008/08/fences_workers_theatre_the_cpt.html (Accessed Mar 20, 2009).

Sainer, Arthur. The New Radical Theatre Notebook. New York: Applause Books, 1997.

Simondon, Gilbert. “The Genesis of the Individual.” Incorporations. Ed. Jonathan Crary and Sanford Kwinter. New York: Zone Books, 1992. 297-319.

Sommer, Doris. Bilingual Aesthetics: A New Sentimental Education. Durham: Duke University Press, 2004.

Toscano, Rodrigo. Collapsible Poetics Theater. Albany: Fence Books, 2008.

———. CPT archives. Online at: http://poeticstheater.typepad.com/photos/rt_pics/ humana_ 3.html.

———. Email Correspondence, May 2, 2009.

———. Platform. Berkeley: Atelos Press, 2003.

———. “Rodrigo Toscano Unzips Three Questions on Poetics.” Online at: epc.buffalo.edu/authors/toscano/toscano_Three_Poetics_Questions_Unzipped.pdf (Accessed Mar 20, 2009).

Natalie Knight’s poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Octopus, moria, 3by3by3, converse, and Slightly West. Her chapbooks Xenia (Furniture Press) and prairies (Scantily Clad Press) were published in Spring 2009. Originally from Western Washington, she lives in Albany, New York and works towards a PhD at University at Albany, SUNY.