| Jacket 39 — Early 2010 | Jacket 39 Contents page | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 14 printed pages long.

It is copyright © Joshua Schuster and Jacket magazine 2009. See our [»»] Copyright notice.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/39/perelman-schuster.shtml

Photo: Bob Perelman

Back to the Bob Perelman feature Contents list

1

Perelman’s poetry is formed in two cities, each with a specific parameter of problems. In San Francisco, his work is preoccupied with the spread of capitalist realism versus the withering of critical platforms, from the fading utopianism of the 60s, to the inability to sustain class or grass roots activism, to the dilution of the radicalism of desire by the near full invasion of commercialism into all human systems of affect. In most of these poems, the poet is thematized in a largely passive-aggressive manner, barely able to record let alone piece together the conflicts, never able to change the situation.

2

In his Philadelphia-based work, the poet emerges as a more distinctive figure/body who desires to assemble the plural temporalities of writing into what Jacques Derrida calls “a memory of the present.” [1] The Philadelphia poems generate more critique and durability based on creating mixed forms that can engage with writing in the long run, to find out how eras of poetry such as the classics and modernism might repeat and reinvent themselves. Yet durability still means being lithe enough to embrace presence, pleasure, nearness, and the now for new poets, poetry, and readers.

3

Perelman wants poetry to oscillate between avant-garde excesses and attentive historicity, using both to oppose the generic, spiritually empty, strip-mall space-time of the American service economy. In these poems, poets and readers must find a way in common to combine evanescence and repetition, or newness and re-reading, “To move, to please / to end up knowing what you know in the present” (Iflife 50). But while swerving between the real and the ideal reader the poem must also navigate away from the culture of administration and the politics of management, where the self and the social are tracked onto paths that displace sensuousness and activism with consumption, reduced expectations, and reaffirmation of the status quo.

4

“Go ahead, make a mess.” A phrase I remember Bob saying to a small group of Penn undergraduates gathered on the grass, spring 1995. He meant, I think, no need to wait for permission for much of anything, let alone the guarded neatness of fresh pen and page. Later I would notice in Bob’s office the single sheet of a Zukofsky manuscript, covered in a disorderly and minute graffiti-like handwriting, and think again of Bob’s suggestion. In other nicely-framed memories hanging in my mind’s wall: Ginsberg visits campus twice that year, the second time performing a full reading of “Kaddish,” and sits in my class on twentieth-century American poetry. Nervous and hoping that my suburban upbringing would not show on my face, I linger after class to ask Ginsberg, “Do you think that everything has been done in poetry? I mean, is there anything left?” Crap, a perfectly suburban question. He responds: “Do you think that consciousness is infinite?” “Yes, I guess.” “Well then so is poetry.” I take this as another permission, and now feel some longing for what seems to me a generous response to a burdensome query.

5

Shortly after I remember Mike Magee recounting that while escorting Ginsberg, Ginsberg dangled his room key saying, “This is for some lucky boy.” A few weeks later Bob mentions that Ron Silliman is moving to the Philadelphia area. I had been writing language-poetry influenced love letters to my tentative girlfriend in the East Bay, California (go ahead, make a mess); for Silliman, I put some lines from my poetry notebook together into a near-nonsensical ramble about how I was excited to meet him and hoping he might teach a class at Penn. For years after, each time upon seeing Ron, my face blushing, outing my embarrassment — but that he said simply thanks for the letter and didn’t bring it up again I file also in the archives of generosity.

6

In capitalist realism (for a recent view, see Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative, 2009) — so dominant of the systems of representation and the modes of production during the 1980s — the world is comprised of nothing more than materials, language, and desire: the circulation of sensory exchange values and the wanting for more of them. There are no larger emancipatory projects or destinies, no commitments to truth, reason, nature, collectivities, or the unconscious. Despite the reductivism inherent to this worldview, capitalist realism is not easy to describe and most art works try to position themselves via formalism or aesthetic purification as far away as possible from the blatant and grubby forms of marketplace life (Warhol, on the other hand, actually used formalism and aestheticism to connect to the marketplace).

7

Perelman’s San Francisco poems, written from 1974 to 1990, aim for the heart of a form that can represent what capitalist realism has done to shape substances, words and affects, while also articulate how the waning of militant leftist causes has only made the need for critique all the more urgent. Yet Perelman is reluctant to pin his hopes on any particular social movement or radical poetic form to effect a long-term revitalization of the left and language. Instead, in To the Reader (1984), skepticism is doing a tremendous amount of lyric work. Phrases like “No place exists even once” are intended to show that there is no refuge from phrases like “I wonder whether ‘States’ in ‘United States’ / Is a noun or a verb.”

8

Such skepticism sets the tone against both an Americanized reality and the likelihood that a better world is around the corner, yet also provides a slim foothold for opposing the status quo and resisting the collapse of counter-discourse. Thus one strategy is for skepticism to side with singularity against the draft of the whole: “Tones of violence make words / The whole truth and / Nothing but the truth, / So help no one in particular.” Such skepticism cannot be the foundation of a widespread leftist programme — Perelman’s work does not aim for this — but it demonstrates a refusal to impose a power, a definitive self or intransigent subject, which helps set critique in motion.

9

In these San Francisco poems, certain tropes recur that are inextricable from the local landscape. AIDS: the address in “Chronic Meanings” oscillates between the personal and the anonymous, the pronouns sliding between the intimate and the absent, reinforcing the ghostly feeling created by lines cut off at five words. Cars and freeways: one is not a functional citizen in California until one can drive; repeated references in Perelman’s poems to bumperstickers, the brief and highly-mediated feeling of freedom when driving, snarling traffic, the all-too-irrelevant pain of finding parking, and the driverless car all fuse into the information highway metaphor of Virtual Reality.

10

Money: in Face Value, nearly all of the verbs in these poems — such as trust, identify, smashed-in, solemnly swear, yoked together, and guarantee — in some way evoke the motions of capital. The long arms of Hollywood: California domestic architecture is laid out in order to maximize the combination of fantasy and consumption, so that rooms are planned around tv, plush sheets, and pornography — giant master bedrooms fitted with king-sized beds, cheap blinds, and remote controls: “There’s no guarantee of identity, / which I can say again, but the second time / is under the sad reign of desire: / chairs, tables, vibrators, VCR’s, personal submissions” (Face 38).

11

High technology: the increasing presence of references to technology, as object and as market, in Perelman’s poems from the 1980s parallels the rise of Silicon Valley, which is understood by Perelman in his early books as largely an extension of the military-industrial complex. Yet the technologization of everyday life also culminates in a 1990s virtual reality that liquefies language and experience, forcing a different kind of writing/reading altogether, which seems to beckon poetry (but what kind and who can recognize it?) back to the cultural front.

12

One year after devouring all the language-poetry books in the university library — no one else was checking them out — I am in Bob’s office, confessing that, yes, I am exhilarated and destabilized, but unable to tease out definite objectives of what to do with all of this writing. Ungenerously I say: “a lot of these poems feel like jelly — and by the end of the poem I can’t remember much of what happened at the beginning.” Looking back, this seems symptomatic of an oceanic feeling that is characteristic of the middle-class experience of late capitalism: language, desire, value sloshing together. Poems that foreground the materiality of the sign over and over were supposed to block or divert the reader from capitalism’s fluidity of all values and experiences and expose how the system works, but to me the poems felt like language, desire, and value made liquid once again.

13

For me, this oceanism with regard to poetry began to be dispelled when I started to hear individual poets read, answer live questions, sit across from me in informal chats, give out hand-produced chapbooks, laugh or glare in my direction. Now it seems obvious that is the way poetry has always been read: not on pages (or sung by voices) alone but necessarily in the company, real or imagined, of other writers and readers for whom any given poem unfolds into a situation that brings the legible close to the livable. The reader — maybe in contact with a scene of poets, maybe not — feels at times peripheral, involved, clumsy, palpitating, bored, politicized, or just curious to find out what happens in the next line: this is what makes the poem possible to be read at all.

14

I realize now that being able to encounter Bob on a regular basis carrying this company, also real and imagined for him, in a public and daily way was one of the most important factors for me to be able to cross over from the threshold of isolated poems and books into poetry literally as a worldly experience. To shift from reading to living out the poem demanded a much greater commitment from me and paid off in making poems much more than just a series of oceanic experiences.

15

Then Penn offered to convert the empty chaplain’s home on campus into a house to showcase varieties of writing. Before the place yet existed, Al Filreis convened a group of students and faculty and asked, in what has become my favorite line for any meeting agenda, “Forget money limits or what the university thinks we should do, what could you possibly imagine us doing in this place?” The room was full of conspirators of poetry. I knew immediately I wanted the place to function not as a “site” for one-off readings but as a poetry world, at least microcosmically: poets would stay for several days, give readings and talks, eat, drink, and linger into the night.

16

Somehow I found myself in the position of coordinating the first visitor, Ben Friedlander (based on a casual list of younger poets Chris Stroffolino gave me). I remember Ben, on the street, remarking to Bob: “your poems have all these mini-narratives that slide into each other but don’t go anywhere together — that’s what’s so great about them.” Bob’s not so sure it is a compliment — can “going nowhere” really be generative or critical? A few months later, Alan Davies is sitting in the living room, with sofa, grey-blue carpet, and just a few people present. Davies says, “I don’t know where to put my poems.” I respond, “You mean, where they belong in relation to other poems and poetic lineages?” “No, not literary history. I mean I literally don’t know where to put them, on the table, on my dresser, over here or over there.”

17

Over the years, Bob has invited over a hundred poets to read in this house, always making sure the poet hung around informally before the reading and answered questions after. Like poets, poems need furniture, kitchens, flowers, time to linger, and time away from their authors. I wonder if Alan Davies has found a place to put his poetry by now?

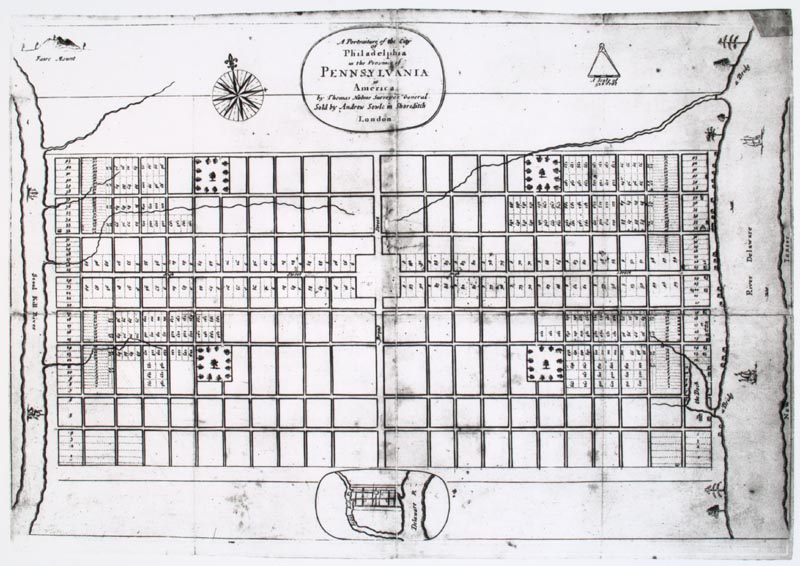

Map of Philadelphia

18

The first map of Philadelphia was drawn before the city existed. Drafted by Thomas Holme in 1683, William Penn commissioned it so he could sell lots in this city of the future. The future: straight lines, orderly, rational, Cartesian, enlightened, open for business. The map is already an advertisement, a billboard. Philadelphia says: here begins capitalism, and the fact that everything outside the city is blank means that already an alternative is unimaginable, the unmarked is just waiting to become another stage for the theatre of capital’s expansion. This is capitalist realism’s own map of utopian fantasy — colonization spreads unimpeded over the local, marks correspond to markets, square parks represent a mastery of nature, and everything is conceptualizable in a single glance. The unconscious, just visible at the edges of the map, is just ready to be tamed and primed for civilization. Yet the blank space also tempts the city made ex nihilo: what could life and thought be like in that undifferentiated plane of existence?

19

Perelman’s poems from 1990 on have emerged from a Philadelphia whose bricks show the wear of multiple booms and busts, the cycles of fantasies and ruins. In Perelman’s work, one finds large amounts of Philadelphia trace material: Poe, Whitman, Marianne Moore’s remnants, Eakins, Muybridge, Duchamp, Penn life, which are now surrounded by contemporary chemical and health insurance conglomerates, doctors, lawyers, academics, service workers, the homeless, and the working poor, all in a landscape shaped by multiple wars and multiple universities. Poetry is often used to explore the space between landscape and fantasy; here is what it is like to drive through that space, according to Perelman’s “Driving to the Philadelphia Poetry Festival at the Free Library”:

20

Emerging from the middle

of a donut-shaped dream, I rolled out of yesterday like there was no tomorrow, turning left

onto Crittenden

with its consonants and trees,

right onto the not necessarily bitter irony of Mt Pleasant, which goes both up and down,

like life they say

but maybe not.

………………

…… I pledge

my allegiance to

the dinky effervescence of what passes for here-and-now, in this case Falls Bridge,

which fails

to live up to its name

once again but does contribute its two cents toward the peaceable kingdom

I’m driving at,

if you’ll accept a ride,

at least part way. I suppose Kelly would have been quicker.

Why are the poetry maps

always out of date,

unreadable, and expensive to boot? “Here be epics, here be epiphanies, here

be state

of the art oceanic

marginalities,” etc. But aren’t poems supposed bring the news, uninterrupted,

spitting out the ads

like a horse

would spit out the bit once it had made up its mind to speak? [2]

21

In this poem, maps side with genres (epics, epiphanies) and their expectations, charting the past and the future, while the present, either the news or the fresh here and now, is where the poem wants to be. But the poem still has to follow some directions in getting there or faces driving in circles: hence maps, Mt Pleasant, libraries, making reading engagements.

22

The opening dream frame is not incidental or accidental; the dream is a longstanding device in Perelman’s poems, such as in the last lines in “China” — “Time to wake up. / But better get used to dreams too” (Primer 61). But in Perelman’s Philadelphia work, dreams awkward and seductive occur with increasing frequency and intensity, from the series of faked dreams in The Future of Memory to virtual realities, elegies to family (“The Dream of the Bed” in Iflife), imagined dialogues with poets and theorists, and dictations from aliens and other lost writers. Let us make the argument here that, in Perelman’s hands, and contra Freud, dreams are the realm of wish unfulfillment. Instead of deflating tension or satisfactorily memorializing the lost, in Perelman’s poems those who appear in dreams (including the figure of the reader of his own poems) are already suffering from distance, disembodiment, and an inability to communicate much at all.

23

In one fake dream Moore, Pound, Eliot and Baroness Elsa von Freytag Loringhoven are marching in the avant-garde together but to nowhere in particular (Trenton, New Jersey), in high spirits but only “with a cartoon intensity” (Future 45) and unable to shout beyond the archive that swallows them in the last lines of the poem. Dreams are sites of synthesis, where different people, histories, and writing styles can encounter each other, but they can dialogue, like Frank O’Hara and Roland Barthes do in one poem, only because they are aware of their meeting in a favored non-space and non-time of the page. They know they will disappear once the poem or the reader awakens, either by turning the page, lifting the eyes, or leaving the reading.

24

The symptoms are slowly colonizing the unconscious; loss, fake memories, and hallucinatory language drive Perelman’s writing and reading but also push these further into places that are not realizable or are fading quicker than ever. In the dream device we see Perelman’s ambivalences toward fusing avant-garde writing with avant-garde politics — where fakery and evanescence make for intense poetic experience, they bode poorly for radical social action aimed at long-term gains. However, there are many ways that we do not want or cannot ever have the poem fusing with the world. The poem is a form of wish unfulfillment too.

25

Yet there is a distinct politics to this specific kind of dreamwork: to be guided by the anxious whims of dreams or the creative fakeness of poems means for Perelman to not be guided by master plans or masters in general. Philadelphia, unlike New York, Paris, or Los Angeles, is not a city with a claim on major art markets or aesthetic movements. There is a Philly Sound but not a Philadelphia School: “dogeared sounds spell the golden mean / throughout the greater Philadelphia area, /… / the place placed here / to mean to be” (Future 68). These dreams and faked encounters do not avoid the scrutiny of judgment, be it aesthetic, ethical, or political.

26

Freud showed that dreams were both systematic and aleatory, thus open to analysis and discernment but never calculable or closable. Perelman is constantly working through a kind of poetics of judgment on fellow poets from Virgil to Pound to Bruce Andrews as much as on himself, relentlessly asking what are the concrete, livable ethics of pushing the limits of poetry? The refusal of a master politics or a universal radical aesthetics for Perelman is not really an embrace of anarchy but a mix-matching of fantasy with self-criticality. There is a Marianne Moore-like moral lesson in Perelman’s combination of evanescence and scrutiny: there can be sensuousness that opposes both absolute sense and nonsense, height without hierarchy, and fantasies that refuse fetishism — but if positions come can reversals be far behind?

27

In graduate school at Penn there were no doctrinaire poetics, politics, or theories. Almost all were leftist and pro the avant-garde. Is this not far from what most experimental poetry had been asking for all along? If previous grad school cultures were organized around rebellious reclaiming of an other that had been denied — the non-normative vicissitudes of sex, the jarring truths of race, the militant mobilizing against imperialism or capitalism — these topics were all more or less available, thus proving real gains. Yet availability also seemed to hint at the analogy of shopping for produce in a supermarket.

28

The greatest danger however was not an absence of political urgency (to get rid of Bush and protest empire were the politics and there was not much of a need for elaborate theory) but the tendency towards lowered expectations, spread amongst some students and faculty. The result was a reluctance to battle over ideas, a vague appeal to dialogue across disciplines, and a general attitude that social critique is for all intents and purposes now divorced from social change. These may be the tenets of academic realism, but it leads to a disconcerting and disheartening belief that theories are all interchangeable, capitalism is here to stay, and personal reward is the best one can aspire to. As if a lack of a shared world could be compensated by our sharing of methods and administrative agendas.

29

I have never seen graduate school as anything less than a place where everything was at stake in one’s thought and writing, despite the obvious fact that grad students do not change the world. Thinking and writing are to me a matter of tying life and meaning. Bob was a dissertation advisor and a guide to how to live one’s ideas. His up-beat demeanor, his beat-up ties, his frequent smiles and chattiness in the university halls, his wavy hair suggesting breeziness, and his tireless attentiveness to poems and students conveyed a profound commitment to the everyday practice of poetic knowledge. True thinking involves chasing away cynicism (whenever the avant-garde turns cynical it gives me dry heaves); I have much appreciated Bob’s rejection of cynical reason from within and outside of the university (where anti-academicism often carries the cynical torch).

30

If I said something about poetry half-baked or unrigorous, Bob would call me on it, saying “Is that really the case?” — a more prodding question than a haughty dismissal. Bob did not affect the “busy” professor — as if busyness was ever an indication of truth or insight. I do not always find myself agreeing with Bob — I’m not convinced that his earnest call for “polygeneric writing” and “self-critical poetry” that he makes at the end of the poem “The Marginalization of Poetry” is particularly radical or contra the status quo — but I am always taken by his beautiful tenacity in following through the implications of what it means to really read and re-read experimental poetry as a life-long dedication. A different world opens when one re-reads. Bob’s writing and teaching is often about what happens when one reads the avant-garde a second or third or fourth time, when the new has to confront lapses of time and distance, when scrutiny of re-reading has to be folded into the burst of wonder released from the first read.

31

This model of how perseverance unfolds seems to me now an excellent one to guide me through issues that I did not fully grasp in graduate school but think that poetry will now be extremely crucial in confronting: namely, the tumbling prospects for the earth, its clouds, and its energies.

32

I read Bob Perelman’s poetry as a set of scattered devices and descriptions that anticipate the increasingly precarious subjectivities facing us in the near future. This is what “iflife” looks like: subjects, action, world, and desire dangling in front of one another as in a baby’s mobile. How we read, live, and string together our scattered narratives, energies, and landscapes means everything for how we might bring about a real earth. We need not idealize the role of poetry or look to it for the formulas of utopia ready to assemble right out of the box; to somehow faithfully record the now while also carving out keyhole-views onto different ways of being is already plenty to ask from the avant-garde. “[T]here are no final surfaces, on earth, in dreams, / no bright pages on which to fix the just sentences” (Iflife 16).

33

The status quo now has to spend enormous amounts of energy, labor, and control just to tread water these days; but just to be able to write the poem “The Revenge of the Bathwater” shows that this water, its residues and flotsam, is ready to make waves and speak out. The truly unrealistic utopia, as Slavoj Žižek points out, its to believe that this now and this status quo can remain fixed and in place forever: “The ultimate answer to the reproach that radical Left proposals are utopian should thus be that, today, the true utopia is the belief that the present liberal-democratic capitalist consensus could go on indefinitely, without radical changes. We are thus back to the old ‘68 motto ‘Soyons realistes, demandons l’impossible!’: in order to be truly a ‘realist,’ one must consider breaking out of the constraints of what appears ‘possible’ (or, as we usually put it, ‘feasible’).” [3] We are caught between the feeling that it is impossible to imagine anything else but neoliberal capitalism coupled with the recognition that it is impossible for this same condition to go on indefinitely without change.

34

In Virtual Reality Perelman rejects the “short-circuiting rhetoric of vatic privilege” (21) projected by grandiose and homespun provincial poems alike, yet short-circuiting is one of the key tools of poets who can monkey-wrench with conditions of existence by combining words and things, the social and the critical. Furthermore, the phrase “the future of memory” is minimally prophetic. Thus one has to put Perelman’s poems to the railroad tracks and listen closely for vibrations coming from this remembered future: In, let us say, 2043, the people’s council reconvenes in Philadelphia to draft a new Declaration of Independence, to be written by one T.J., denouncing all kings, unhinging us from our servitudes and our own dominations of others. A bill of rights is put forward that would not make human rights the only rights in town, but would extend justice to all iflife. A constitution will only be drafted much later — for now the world gets to enjoy the moment suspended between rebellion and juridicizing, not unlike how “the future will lie down / with the past” (Future 96) in the realm of the fake dream.

Derrida, Jacques. Memoires: For Paul de Man. Trans. Cecile Lindsay, et. al. New York: Columbia University Press, 1989

Perelman, Bob. Primer. San Francisco: This Press, 1981.

———. To the Reader. Tuumba Press, 1984.

———. Face Value. New York: Roof Books, 1988.

———. Virtual Reality. New York: Roof Books, 1993.

———. The Future of Memory. New York: Roof Books, 1998.

———. Iflife. New York: Roof Books, 2006.

Žižek, Slavoj. “The Prospects of Radical Politics Today.” International Journal of Baudrillard Studies 5:1 (January 2008).

[1] “What if there were a memory of the present and that far from fitting the present to itself, it divided the instant? What if it inscribed or revealed difference in the very presence of the present, and thus, by the same token, the possibility of being repeated in representation?” (Derrida 60).

[2] Bob Perelman “Driving to the Philadelphia Poetry Festival at the Free Library,” DC Poetry Anthology, 2003. http://www.dcpoetry.com/anthology/105

[3] Slavoj Žižek “The Prospects of Radical Politics Today,” International Journal of Baudrillard Studies, 5:1 (January, 2008). http://www.ubishops.ca/BaudrillardStudies/vol5_1/v5–1-article3-Žižek.html

Joshua Schuster

Joshua Schuster is an assistant professor of English at the University of Western Ontario. He finished his Penn undergraduate degree in 1998 and his Ph.D. there in 2007. Two of his poetry chapbooks, Project Experience (1999), and Theatre of Public Safety (2008), have been published by Handwritten Press. He has essays on modern poetry in the Journal of Modern Literature, Open Letter, and Shofar, and is currently working on a book, Organic Radicals, about modernist American poetry and environments.