| Jacket 39 — Early 2010 | Jacket 39 Contents page | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 20 printed pages long.

It is copyright © Francie Shaw and Bob Perelman and Kristen Gallagher

and Chris Alexander and Jacket magazine 2009. See our [»»] Copyright notice.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/39/perelman-shaw-iv-kg-ca.shtml

Photo: Bob Perelman

Back to the Bob Perelman feature Contents list

JACKET

INTERVIEW

Francie Shaw and Bob Perelman

in conversation with

Kristen Gallagher and Chris Alexander

New York City, mid 2009

This interview took place in the New York apartment of Bob Perelman and Francie Shaw in the (northern) summer of 2009. Present were Bob, Francie, Chris Alexander, and Kristen Gallagher.

1

Kristen Gallagher: I wanted to talk to you about the nature of the collaboration in Playing Bodies. Which came first, did you do the paintings and then Bob wrote in response to them?

2

Francie Shaw: I did the paintings about a year before he wrote the poems. I can’t remember exactly, but it was a substantial amount of time, I think it was a year.

3

Bob Perelman: Two.

Francie Shaw

4

FS: It might have been. We could figure it out, the paintings are dated 2000. There are 52 of them, all 20 x 20 inches. I did a series that fit around the perimeter of my studio. That’s why there are the number that there are, because that’s what fit. I wasn’t thinking about cards in a pack or anything, twice the alphabet. In fact I have a few more that I just didn’t like as much. Bob said he wanted to write about them, and then when he was on sabbatical he started writing them. When I checked in later he had almost finished them all. And then we went through them, and with some of them I said I didn’t like this or that because it was too different from what I had in mind, although all the paintings are ambiguous in my mind.

5

BP: Well you often vetoed poems that weren’t ambiguous enough.

6

FS: Yeah, that’s right. I love the poems, and I feel really good about the paintings. But I’m still not sure about the combination. I mean it works, but sometimes I think that the paintings are better without the poems. And the poems certainly stand on their own without the paintings. It’s a different kind of collaboration than the earlier pieces we did which were really interdependent.

7

KG: Do you say that they can stand separately because you have concerns that the poems frame the paintings too much?

8

FS: Yeah, and also it’s partly because of the way you experience it. I also have some regrets about the printing in the book. It is too hard to see the brush lines, the texture. The cover image, which I like, is bigger than the actual image, shows much more of what the paintings look like than the ones inside, which could be ball-point pen for all you know.

9

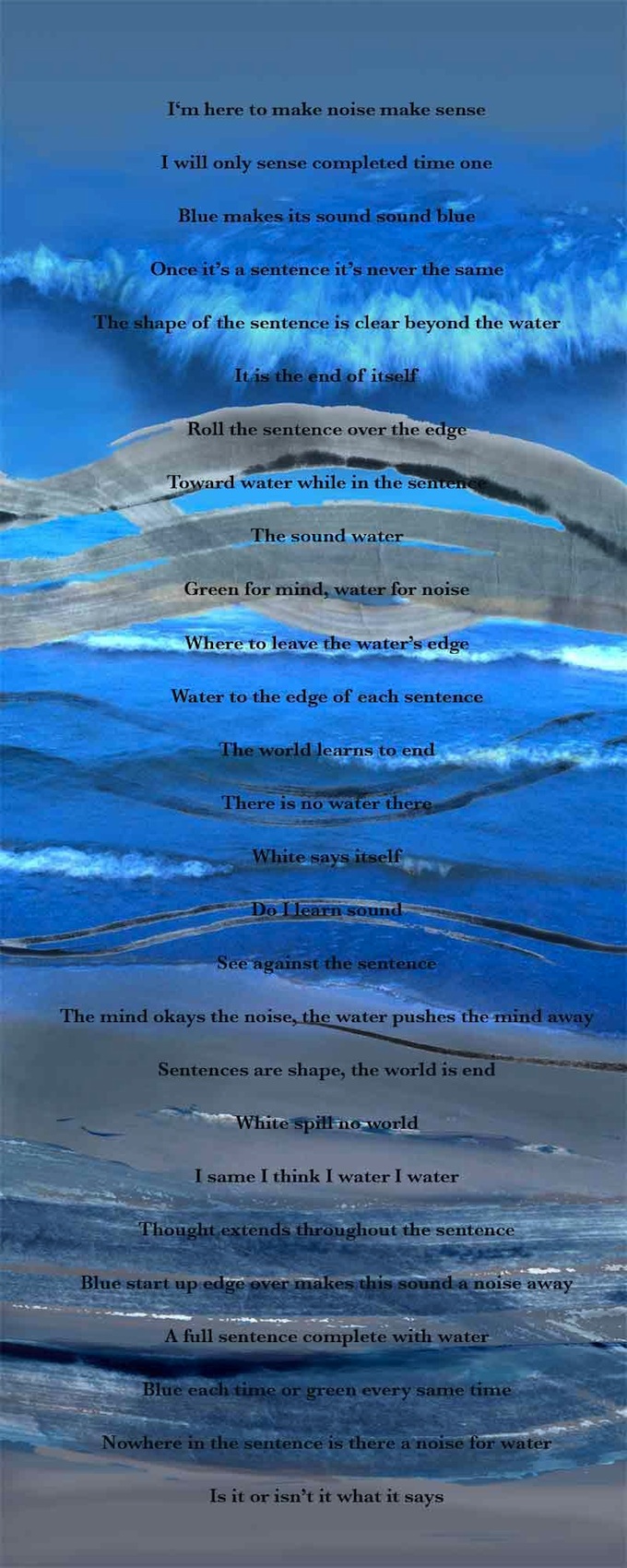

BP: Well that’s what some people thought, that they were ball-point pen.

10

KG: Have you encountered this problem when you perform them together?

11

FS: Not the ball point pen problem, but another problem. You’re seeing slides and hearing Bob read, and so the sound takes much longer than seeing the image, so the sound becomes the dominant mind-picture for what you’re experiencing. Maybe we could think about doing it some other way when we present them, but he’s always reading to each picture, and he did write a poem for each piece.

12

KG: So you stopped doing the performance because it wasn’t working?

13

FS: No, not that. It gets boring doing it over and over, but really nobody else has asked recently, and we’ve been doing other things.

14

KG: Can we talk about earlier collaborations?

15

BP: I want to say for your interview, in the new Grand Piano [8], my piece is about two older collaborations Francie and I did, and it goes into some detail about them.

16

KG: I heard you read that at St. Mark’s. The piece described a performance where you, Francie, were drawing while Bob was reading something? What year was this?

17

FS: I think this must have been 1977 or 78. During the performance I was drawing in ink on prepared pieces of paper that already had drawings on them.

18

KG: So you were drawing on your drawings while Bob was reading? How do you remember that event, and why drawing over drawings?

19

FS: I’ve always loved layers, changing foreground background stuff, it’s the way we see the world really. You always have to choose what to foreground around you and it always changes. There were two pieces we did. The first one was based on a grid, I think 5 x 5, of drawings on 18” x 24” paper, or something standard, and rectangular. And they were all drawings of a plant I had. It was a flat-leafed bromeliad, and it only had seven leaves on it. I drew it from different perspectives. I was already working on that plant; it’s on the cover of 7 Works.

20

I had a lot of slides from when I was teaching kids. It’s something I did that kids love (kids now probably don’t know what a slide projector is) where you take a blank slide and draw on it with magic marker or ink, but ink is a better material, and you can put rubber cement and cellophane on it and the rubber cement moves around in the heat of the projector lamp, and everything is much bigger projected. I started drawing on top of the used slides with black ink. The slides were mostly bright colors, and I would draw silhouettes of the plant, and that generated the form to some degree. I think I was working on the slides before we knew exactly where we were going with it.

21

KG: So let me get this straight, you were drawing on the slides, or on something where the slides were being projected?

22

FS: I was drawing on the slides themselves with a little steel-tipped pen, and then projecting those onto these drawings on paper of the same thing, and then during the performance we had the actual plant there, and we put the plant in front of the projector, and that cast shadows on the grid of drawings, and then I traced those shadows. But it was one plant going across all sixteen drawings. We have no record of that performance, I mean, I have the actual pieces of paper covered with drippy black ink, but they don’t indicate what we did in the performance.

23

BP: It was a great idea, and I’ve never heard of it done.

24

FS: Steve Benson has done some things sort of similar, but entirely different too.

25

BP: I had two tape recorders, and somewhere in my box of papers — which is this over-sized, Freudian black box I haven’t dealt with yet — but somewhere in there I have this over-sized piece of paper with four different tracks of sound written out. The first layer was a gappy track that I pronounced and recorded. And then I played it back, and while it was playing I was speaking the second layer into the second tape recorder while playing the first, to get this two-track piece. And then I played that back while I spoke and recorded the third track. And then again. It wound up a four-track recording. It was about Plato and shadows. It was a mix of philosophical and popular culture stuff, and it was definitely in response to Francie’s work. In all our collaborations it seems Francie has always taken the lead and I think, Oh this is something that will fit in with something she was doing.

26

KG: So what exactly was the origin of the collaboration on that piece? Did Bob notice what you were doing teaching, and he started writing about it?

27

FS: No, I wasn’t teaching right then. I remember sitting in the loft where we were living on Folsom St., it was all one big space. It was a neat space, an old flea-bag hotel, and it was the top floor of a three floor building, and the people who had been there before us had taken out all of the interior walls, and left a few flimsy 2 x 4 posts in there. It had been ten tiny rooms, something like that, and all of a sudden all the walls were gone, and the ceiling jiggled profoundly every time there was a small earthquake. It was the tallest building on the block, so it had windows on all four sides, and the previous occupants had painted the entire space white, the walls, the floor, and it was funky, a fun space to work in. So I remember sitting at my drawing table working on the slides, and Bob was sitting near me working on stuff, and we were talking back and forth while working. I didn’t know about Plato’s cave, so that was very fascinating for me, and that’s one of the things that was really fun for me, and always has been when working with Bob. He thinks about all sorts of things that I wouldn’t think about otherwise and the reverse too. It’s exciting.

28

KG: So you were talking back and forth while you were making the pieces, and then it seemed natural that you would perform that somehow?

29

FS: I don’t know exactly when, but at some point early on we had a date for doing the performance at 80 Langton Street as it was called then. And things were undefined enough that you felt okay doing something where you really had no idea what it was you were going to be doing.

30

BP: The bar was very low. And I’m very happy about the memory of those performances, as they were quite interesting. There was very little sense of being pinned up on the wall and measured. You know, like, “How good are you at this?” Both performances that we did, we hadn’t seen anything like what we were doing.

31

FS: And neither of us were involved in the performance scene. We were naive. There was more stuff going on in San Francisco, but we didn’t know it well. I had a lot of prejudices about performance. A lot of it seemed really boring or didactic. None of it seemed to be thinking on your feet or through your brush. And I’ve never actually seen performances where people were drawing like I did. I might have seen Joan Jonas by then in “Juniper Tree” using drawing as a of part of the performance, a sort of incantation, very beautiful. She did it in Berkeley, at the University Museum.

32

I think we had first agreed to do our Before Water piece. I had this idea in my head of filming ocean waves coming in again and again and again. I was beginning to experiment with film. We would go to films and were getting educated. My movie of the ocean was one position of the camera, just straight shots, and I can’t think of it as a particularly interesting film.

33

BP: It was 20 minutes, right?

34

FS: I think it was 15, I’m not sure, many spliced 3 minute reels. And clearly that single image wasn’t enough, and I started reacting to it. I was trying to enact the particular curl of a particular wave. I had a long piece of prepared white butcher paper with lines painted on it like waves.

35

BP: And washes of blue and green.

36

FS: Blue, green, and charcoal. I think I painted with blue paint during the performance. We worked on the idea together, and then the writing happened after. We don’t even remember the name of the other piece. “Figures,” or something, I don’t know. Before Water was a mesmerizing piece, I loved that one. Hearing that while Bob was working on it helped me think about what I was doing.

Before Water

37

BP: That one was very much at Francie’s instigation. I’m very happy with that poem, it was me running after Francie: “Wow, that’s a really interesting idea to imitate ocean waves, what’s the difference between same and different.” I talk about all of this in The Grand Piano. It was an exciting idea that I never would have had by myself. I mean I had heard of St. John Perse and his epic about the sea I guess, but that’s not of interest to me. (Not that I’ve read it, either.) But basically it didn’t come from my literary background. It was definitely from an idea Francie had. Then for me the question was how long can I keep it up? Can I write non-identical, similar permutations on this notion of a wave coming in? The infinity of the ocean and the finite wave. It was a powerful, open-ended notion.

38

FS: We just jumped right in. We weren’t involved with performance stuff, though Langton Street, where we did it, was a performance space at that time.

39

BP: I was on the board —

40

FS: — you weren’t on the board until after our performances though. Steve Benson had done pieces that were more performance than anything else, but we stayed mainly in the poetry context — well, some other stuff, music, some performances. Unfortunately we didn’t consider video-taping our performance, which even back then would have been possible to do. Then we did a piece a year or a year and a half later at the San Francisco Art Institute with Larry Ochs playing saxophone. That was right after Max was born, 1979. Bob, do you have any record of what you wrote? I have some pieces of the film stuff, and I think it was really interesting what I was doing, and would love to able to get back there. That one’s washed out in the water like a Tibetan sand painting, gone. For that, I shot film of the stairway at the Art Institute, where we did the performance. It’s sort of at the top of Telegraph Hill, and you go up and up these outside concrete stairways. That’s basically what I filmed, and some of what you can see from around there, rooftops and laundry. I’ve always loved the optical illusion that you get when you can look at stairs and they seem like they can go either way, when you separate what you see from what you know. The next stair could go up or down. For that performance, there were four long panels, about 4x8 feet each, that had prepared screens, each with several layers of paper. I painted on top of them, like with the first performance, the plant one. After painting on a prepared sheet of paper I ripped it down and there would be another fresh prepared paper underneath. I needed another clean surface. Once it’s too busy/dark you can’t see anything, the fresh pieces of paper allowed the film to be visible. When it is dark with ink you can’t see the moving images. There was this litter that was accumulating from all the layers, very noisy too.

41

Chris Alexander: And during this you were to the side reading?

42

BP: Larry Ochs was playing, saxaphone, and we worked out these protocols for sonic solos and sonic duets.

43

FS: And there were times I wasn’t doing anything. I don’t remember what we called that work either.

44

BP: Two by four?

45

FS: No, that was the show I did at Langton Street. Actually, that one was called Light Ground X 4.

46

KG: So would you say a tremendous amount of your work back in that period was collaborative? Were you always sitting next to one another working?

47

FS: No, I’d say much less than half of our work was collaborative. Certainly for Bob because he was extremely productive then. I think it was less than half of my work. I was mostly painting. I was doing some big, really big, paintings, part 3-D, which were really good, simple. And an installation at Langton Street which had translucent paintings and a super eight film. I have some other films left from that time, but I’m not all that interested in most of them. Steve Benson and I did a movie, which was another fixed idea I had, but it turned out to not be that good. (Laughs.) I’d like to take a look at it again sometime. We made a dinner for twelve people. We had a long table set up in the studio, and we had plates and things that I was fond of, things I thought looked nice, a hodge-podge of silverware. And I think we had Cornish game hens, something that changed a lot as you ate it, and we just filmed that, sort of an animated disappearing feast. We filmed people eating, and I think it was pretty boring, except I remember one shot which was really good, which was through Alan Bernheimer’s glasses, from his point of view. But we did a little editing on it. It was also a silent film. All of mine were.

48

BP: There was a pretty constant sense of “our lives, our art.”

49

FS: It was still a little bit like the flower children, or something like that, just that we were such kids! There were people who had real kids. My sister had 2 kids, Lyn [Hejinian] had kids. And there were a core of kids who would come to the Grand Piano readings, and they would be under the piano drawing. But none of our close friends, except for Lyn and my sister Sue had kids then. Ahni had a child, but she wasn’t really around much then, I think, more up-country. Then I was the one of the first ones of our little group who got pregnant. Rae had just moved to San Diego, and their son Aaron is about seven months older than Max.

50

KG: So having kids changed things?

51

FS: It changed things a lot. What was I doing for my children, for my life? I had postpartum depression, on top of the normal depression I discovered I always had and I just stopped working. I couldn’t deal with it. I mean, I didn’t stop totally right away. And having a child is so satisfying, so completely engrossing, why go somewhere painful when you can cuddle with a baby? When Max was two we moved from the loft we were working in on Clyde St. to Berkeley. I had a studio in the garage at the house, but I didn’t use it that much. I was working on finishing a film when we were moving, which I did finish, that one is good, but I never showed it to anyone except for one friend, Warren Sonbert, the filmmaker. He liked it. I’ve always thought of it as my dying Swan movie, because I felt like I was dying artistically and there is a swan in it, not a dying one though.

52

KG: It took awhile to get back?

53

FS: It took a long time.

54

BP: Well, you taught.

55

FS: I taught again. I had kids in the studio in the afternoons, doing art classes, which was really fun. And then I got a real job teaching art in an elementary school that was just starting. And that was fun because I could control from the ground up how art was defined there. It wasn’t until much later when we went to England for a year, that I really started working consistently again.

56

CA: What year was that?

57

FS: ‘96? So ‘82 to ‘96 I wasn’t doing my own work.

58

KG: Not until the kids started having their independent identities?

59

FS: Yeah. They didn’t need me as much. But it was more that I “grew up.” I did serious therapy work and started anti-depressants. I remember when I told one of our kids that I was going to quit teaching to do my own work, he said, “You don’t want to be a teacher anymore? But you are a teacher, that’s what you are!”

60

BP: I just want to interject and say that Francie was a very powerful art teacher, among other things.

61

FS: Well I did like teaching. It was rewarding, you could go to work every day knowing that you were doing something worthwhile, that you enjoyed, and that the people you taught enjoyed. It’s such an immediate satisfaction. It was intellectually stimulating and rewarding. It served me well for a long time. I still sometimes dream about the kids, and teaching.

62

KG: It was a generative environment?

63

FS: If you’re really doing it, you’re noticing practice just as much as you do if you’re hanging around with adult artists. So that was very liberating for me. But I can’t wear two/three hats. I’ve never been able to do that. I mean the mom thing and the job thing, I loved it, but I just couldn’t also be an artist while I was trying to do both. Then later there was the whole adjustment to Philadelphia, which was very traumatic for me. Even though it all turned out fine. I just didn’t have enough confidence, or a clear enough idea of what it was I wanted. I’m terrible at the whole professional part of art. I just don’t do the things I’m supposed to do.

64

CA: The whole go-getting thing, it’s such a drag. It was interesting when you were saying earlier about your time at the loft that the stakes were lower —

65

BP: — the bar was lower. Your little bean spasm was OK: “Oh that’s interesting, go ahead and do that.” There wasn’t a lot of third and fourth guessing in a crowded scene about what’s the best move to make.

66

FS: No, we weren’t thinking about that at all. Plus there was so much more time somehow. If you didn’t like it, well then you could do something else. You didn’t have to have everything you did be the be-all-and-end-all. But really, it was about time. Time to follow through an idea, to MAKE it interesting. I don’t think the bar was lower, actually, at all. It just didn’t hang on categories, you could try anything. Of course, you always can but sometimes it’s hard to remember that.

67

KG: So process was a little more understood?

68

FS: Yeah, very much. It was about being in this scene and bouncing off each another and enjoying what other people were doing. And also I think people were appreciative of one another’s efforts. So if you did something it was a gift to other people. Which is a more generous foundation to be operating from, than what often currently happens for people. Also we were younger and had more energy then. We would stay up a lot later, and drink more and smoke more dope, you know. People weren’t working as much, it was much cheaper.

69

KG: The cheapness needs to be considered, and the different pressures of time that existed. It sounds like you were in a looser configuration as far as having established terms in which you were supposed to be working. It doesn’t sound like you had a lot of received forms.

70

FS: There was definitely a form of The Reading on the poetry scene. The public aspect of it was demanding, and you were expected to contribute if you were a writer. For those of us who weren’t, we had more freedom if we were staying around that scene. Well, it was freedom for the writers to read, I suppose. I came from a chaotic schooling background, in Chicago and Boston. I was changing my practice a lot. My work had been very diaristic, funky. Sort of animistic. I loved the book “Black Elk Speaks,” Georgia O’Keefe, Frida Kahlo, the Feminist Heroes. But when we moved, I think I got much braver, more formal. And I’ve always been lucky to have a lot less financial pressure than most people. It’s so much harder today, so professionalized, so “can I get health care” dominated. But I think the determination and need for cheap available artistic forms are still the same.

71

KG: I wanted to ask you about the Writing/Talks series. That started in your studio, right?

72

FS: That started in our loft on Folsom Street.

73

KG: Were you involved with that?

74

FS: I wasn’t involved with the organizing, but I made posters. We still have some of them. I had a lot of rubber stamps from teaching kids, which I would use, and then take the results to the copy center. It was exciting when you first discovered Xerox stores! Wow, copies! I would make a bunch of those.

75

BP: I was amateurish about it; I didn’t develop a mailing list like I should have. I was much more low-key, like, “Oh you’re interested? Well, here’s a flyer.” You could come to the talks and there was no cover charge.

76

FS: Sometimes we would collect money if someone bought beer from “Canned Foods “ down the street. You could get a 6-pack for —

77

BP: 89 cents.

78

FS: It was this white can with big black letters on it that said BEER or something.

79

CA: I’m trying to imagine this loft space. It’s your space, it’s a home space, it’s a living space, it’s your studio, you’re both working there, the talks are happening there. It sounds like a foment, like an art petri dish.

80

FS: The space was long and skinny. It had bays, so it kind of went in and out, in and out. In the back it had a toilet in one closet, then a bathtub in another little room next to it, which was great. I have a great picture of Bob in the bathtub.

81

BP: I don’t like to take baths.

82

FS: Well you had to take baths there because we didn’t have a shower. And there was a utility sink and a little tiny stove. And I think we got a refrigerator or something, and there was actually a washing machine, which was really great. Then we’d just hang the laundry up around inside.

83

KG: Before we finish, I just wanted to ask you — since you’ve known Bob for so long — do you know of anything from Bob’s background that made him so attentive to language or rhetoric, that made him become a poet or attracted him to the avant garde?

84

FS: Well, Bob’s childhood was very culturally barren. His mother was very smart and had been to the University of Chicago, but she didn’t display her sophistication. It wasn’t okay. But she read a lot. So there were books around, like Last Exit to Brooklyn, that she had read, which was kind of ballsy of her where she was in Youngstown. But I think it’s partly because it was so deprived that you kind of have to develop your own resources. Bob described to me playing games like opening the encyclopedia to a certain page, or taking books with submarines or war machines and throwing things at them, and playing these elaborate games. Boy stuff. But I think it was a book with words in it because he wouldn’t have done it without words. He was always interested in words. He was lucky enough to go away for high school when he was young, and learn about poetry. For the avant garde, I think that he was open to it. At it’s best it’s surprising, inventive, smart and funny and so is he. It was falling on rich ground that had been barren and ready for something. God, that sounds ridiculously romantic. What makes someone be different from those around them? It’s a mystery.

85

KG: You two went to the same high school, right? That’s where you met?

86

FS: Well, we didn’t really meet. We think we never spoke to each other the whole time and it was a completely different experience for each of us. I mean we must have had the same classes at some point, there were only 40 people in our whole grade. I didn’t hang out in the Typing Room with the other readers/talkers/writers. I was never a word person. I hung out in the sculpture studio and in the woods and meadows (this was Vermont). I mean people’s brains work in different ways. Words, and music too, he could have gone into music instead. But it was more fun with words than with music, more to make up than the classical music he was exposed to. When I met him again later, maybe I was 23.

87

BP: No, you were 24.

88

FS: But he was writing poetry, and the first night we were together he said, “Let me read you a poem of mine.” Ha, what romance! My mother had always loved poetry, talked about it, read it to us some but I never really thought anybody was a poet. I don’t know what that poem was either, it’s long disappeared into notebooks somewhere, never to be seen again — for good reason, probably. But he was just interested in ideas, and I remember he was in Iowa then. Being identified as avant garde didn’t compute for me. Counter-culture, that was your identity. You didn’t need to do anything besides that, then, at least in my mind.

89

KG: Can you say more about what that meant for you?

90

FS: It was 1971. I thought you had to live ‘outside the system” as if one could, or that I did. I was trying to make a world for myself that wasn’t what my parents did, you know, the same old thing. Also the Vietnam War, being anti-authoritarian, changing the system etc. It was still a bit of a shock to our parents that we lived together without being married. But the art part was nothing new for me. I grew up in an arty family. My parents were both educators but they wanted to be writers. I was always tagged as “going to be an artist” but I thought that was because I couldn’t spell. Actually though, my maternal grandmother was a successful sculptor and I think I was supposed to take on the mantle and I always did love art. If you really want to know our personal timelines, the first year 1971, Bob was still finishing school in Iowa and I was at the Museum School (School of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts). Then Bob had a job for the International Writing Program in Iowa City and we went there for a year. A weird year for me, so isolated in the tiny town of Hills. Then back to Cambridge. We lived in a house with other people, had some great friends but it was hard for Bob in Cambridge, too WASP. He felt surrounded by nice old ladies who would take his classes at the Cambridge Adult Education School, in Harvard Square. His writing connections weren’t happening then, though we did see some of Bob Grenier in those days, going up to Franconia to visit, or sometimes he came down. That’s how BG met Michael Waltuch and “Sentences” happened.

91

BP: Through Grenier I met Zukofsky and Creeley and all of a sudden realized, “Wow, these are real human beings, aren’t they?” It was exciting.

92

BP: Creeley taught summer school at Harvard and —

93

FS: Oh yeah and you did that.

94

BP: John Yau was in that class. The one thing I remember clearly is Robert Creeley saying with total disregard of personal boundaries — “Bobbie was having her period then.” Suddenly this giant exclamation point appeared over the sky, and I thought, “Oh my god you can say that?” That’s part of what for Creeley being a poet was about. And then on the other hand I remember the time that Zukofsky talked to me for quite a while about his rehearsal of western literary history via oin- sounds in Greek, etc. So you know, it isn’t as though poetry was just all one thing. But anyway, I started to meet these people. Realizing the intensity of interest and dedication was a complete, permanent eye opener.

95

FS: We wanted to move someplace else. I was happy to go. I grew up in Cambridge and it seemed like a good idea to move on, though I was content enough there. We were either going to move to New York or San Francisco, because those were the two places where Bob was interested in what was going on. Either place sounded interesting to me. But my sister lived in Berkeley. By then Bob’s identity was more just who he wanted to hang out with than mine was. When we moved to San Francisco it became clear right away that that was indeed the place where we needed to be at that moment, for him. For me I don’t know, it was just sort of amorphous. Well, the family connections have always been really important to me. I’m lucky, I’m close to my siblings, pretty much always have been. And I had lived in Berkeley for a little before and I liked California, it was more familiar than NYC.

96

KG: Poetry-wise, you wanted to move to New York or San Francisco because of the people you were in contact with?

97

BP: Yeah. And I had lived in the Bay Area before. I was never a social go-getter, it was always a sort of lucky accident of meeting people. Many people were social go-getters and kept their eyes out for interesting people. I just had good luck running into interesting people.

98

FS: I don’t think it’s luck, they are attracted to you, your enthusiasms, your writing.

99

KG: Who are you thinking of?

100

BP: It’s the same people who have stayed my friends and associates and contacts. I’m just saying it’s not like I had an eye out for who was out there doing interesting stuff —

101

FS: We’d been out there to visit, and he’d known Barry [Barrett Watten] from Iowa. And he’d met Kit [Robinson] out there.

102

FS: We didn’t have a place or connection for poetry, or art, as much in

New York. We had met Bruce Andrews when he was at MIT. He was in Cambridge at

the same time we were, but we didn’t connect really, back then. I think we

met once or twice. I had a good friend from art school in NYC, she was living in

a loft on Canal St. New York was cool, it was history, real artists, all that.

California seemed more open, easier to move into and also more exotic. So

that’s what we did. We piled all our stuff into the little homemade house

on the back of our yellow pick-up truck, tied some chairs to the roof, my cow

skull in front, took the dog and went to California.

Transcribed by CA Conrad

Christopher Alexander lives in New York and on the internet. The first release of his work Panda: will appear this spring from Truck Books. You can follow the beta dissemination of Panda: on his tumblr. http://hedorah55.tumblr.com http://twitter.com/hedorah55

Kristen Gallagher was born and raised in Philadelphia and went the University of Pennsylvania from 1987–91 and again from 1995–99. She was an early member of the “hub” of the Kelly Writers House, edited The Form of Our Uncertainty, a tribute to poet and publisher Gil Ott of Singing Horse Press, and founded handwritten press, publishing early works by Michael Magee, Joshua Schuster, Alicia Cohen, and Nathan Austin, among others. She received a Ph.D. from the SUNY Buffalo Poetics Programs in 2005 and is now Assistant Professor at LaGuardia Community College. Her work on Paulo Freire received a UCLA Paulo Friere Institute Reinventing Freire Award in 2007, and a recent essay “Teaching Freire and Open Admissions” was published in Radical Teacher. A review of Tan Lin’s Heath Plagiarism/Outsource is forthcoming in Criticism, and her first book of poetry Reading A Map, will be published by Truck Books in 2010.

Bob Perelman: see the bio note in this issue of Jacket.

Francie Shaw was a 1946 first-of-the-baby-boomers baby, whose father was just back from the Pacific. She grew up in Cambridge MA with parents who were both educators. She has two sisters and a brother from that time; two more brothers came later. She went to college, then art school in Chicago, but didn’t finish either. She had chickens at an old farm in Boxboro MA, lived in a boarding house around the corner from the Black Panther’s office in Berkeley in 1969, had an unheated studio with a silver ceiling in Cambridge and other minor adventures. She finally finished school at the Museum School in Boston. By the time she graduated she had met Bob. In 1976 they moved to San Francisco, where she had a one-person show at 80 Langton St. in ’78 and she participated in some other shows and the Poet’s Theater. They had two kids, lived in Berkeley for nine years and moved to Philly in ’90. She was an elementary art teacher in California and Philadelphia, then went back to her own art practice in ’97. She is now a member of A.I.R. Gallery in NYC, where she’s had three solo shows, and will have another in April 2010.