| Jacket 39 — Early 2010 | Jacket 39 Contents page | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 8 printed pages long.

It is copyright © Mark Silverberg and Jacket magazine 2009. See our [»»] Copyright notice.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/39/silverberg-koch-intro.shtml

Imprint: Ashgate

http://www.ashgate.com/isbn/9780754662983

Illustrations: Includes 10 monochrome illustrations

Published: March 2010

Format: 234 x 156 mm

Extent: 296 pages

Binding: Hardback

ISBN: 978-0-7546-6298-3

Price £55.00 Website price: £49.50

BL Reference: 811.5'4'0997471

LoC Control No: 2009036663

From the dust jacket: In the 1950s and ’60s, New York City was the site of a remarkable cultural and artistic renaissance. Mark Silverberg examines this rich period of cross-fertilization between the arts, focusing on five major poets — John Ashbery, Barbara Guest, Kenneth Koch, Frank O’Hara, and James Schuyler. This is the first monograph to treat all five the New York School poets. Silverberg uses the term “neo-avant-garde” to describe New York School Poetry, Pop Art, Conceptual Art, Happenings, and other movements intended to revive and revise the achievements of the historical avant-garde, while remaining keenly aware of the new problems facing avant-gardists in the age of late capitalism. Silverberg highlights the family resemblances among the New York School poets, identifying the aesthetic concerns and ideological assumptions they shared with one another and with artists from the visual and performing arts. A unique feature is Silverberg’s annotated catalogue of collaborative works by the five poets and other artists.

To comprehend the coherence of the New York School, Silverberg demonstrates, one must understand their shared commitment to a reconceptualized idea of the avant-garde specific to the United States in the 1950s and ’60s, when the adversary culture of the Beats was being appropriated and repackaged as popular culture. Silverberg’s detailed analysis of the strategies the New York Poets used to confront the problem of appropriation tells us much about the politics of taste and gender during the period, and suggests new ways of understanding succeeding generations of artists and poets.

1

Sometime in 1954, Frank O’Hara and his partner Larry Rivers, the enfant terrible jazz musician turned painter, wrote a play entitled Kenneth Koch: A Tragedy which, O’Hara later recorded, “cannot be printed because it is so filled with 50s art gossip that everyone would sue us” (OCP 514). In many ways, the play provides an ideal example of the New York School text and attitude which will be the subjects of this study. An improvised, collaborative production, the play began during one of O’Hara’s many modelling sessions for Rivers as a way of keeping the model amused. And with typical New York School nonchalance, it was abandoned when its momentary usefulness was exhausted; the play remains incomplete.

Detail: Frank O’Hara, Larry Rivers, and Grace Hartigan at the Five Spot, 1957, photo copyright © Burt Glinn, 1957

2

Regardless of (or perhaps because of) its gratuitous and casual genesis, Kenneth Koch: A Tragedy is a fascinating, self-reflexive document which uses parody and self-parody to examine the conditions of artistic production in New York in the 1950s. This is a play about the “New York School” which both enacts and satirizes the qualities of the movement. This doubleness is refreshing, especially given the fact that the New York art world of the 50s and 60s has developed a rather hallowed mythic aura (produced through the initiative of the artists of the time and with the help of critics like Clement Greenberg, Harold Rosenberg, Thomas B. Hess, Irving Sandler, and David Lehman). Lehman’s The Last Avant-Garde: The Making of the New York School of Poets presents New York in the 50s and 60s as America’s answer to “Paris in the golden period before World War I” (1):

3

The poets of the New York School were as heterodox, as belligerent towards the literary establishment and as loyal to each other, as their Parisian predecessors had been. The 1950s and early ’60s in New York were their banquet years. It is as though they translated the avant-garde idiom of “perpetual collaboration” from the argot of turn-of-the-century Paris to the roughhewn vernacular of the American metropolis at midcentury. (2)

4

Frank O’Hara thus becomes America’s Guillaume Apollinaire, and Abstract Expressionism becomes its Cubism. It is instructive to compare Lehman’s romantic version of New York to one presented by Larry Rivers:

5

There is no doubt in my mind if the idiots and garbage collectors who shovel up ideas for Hollywood and T.V. run out of material, even further than now, our lives could easily be made into a cornball modern Vie de Boheme. Instead of calling it Moulin Rouge with a dwarf and a few whores it could be called “The Cedar Bar” with fags, dope addicts, and an endless and exhausting amount of “names.” (92)

6

Rivers’ language seems more accurately expressive of the artists’ attitudes than Lehman’s. The New York School poets and the Pop and Neo-Dada artists who were their contemporaries were not “belligerent” radicals (as the Abstract Expressionists frequently portrayed themselves) but rather more sophisticated and shrewd producers. They didn’t just revocalize the modernist language of Paris circa 1920 in a “roughhewn” American vernacular, but responded to the historical avant-garde in much more complex and comprehensive ways, providing a counter-discourse to their modernist precursors and “heroic” contemporaries. The New York School poets applied a keen historical awareness of both the conditions of avant-garde production in the first decades of the century and the compromised situation of the avant-garde in America in the 1950s and 60s to create a neo-avant-garde aesthetic, an aesthetic which both revived and revised the so-called “historical avant-garde” (that is, those movements of the early part of the century such as Futurism, Dada, and Surrealism). The term “neo avant garde” has been used mainly by art historians to discuss a group of movements (Neo-Dada, Nouveau Réalisme, Fluxus, Pop, Minimalism, and Conceptual Art) in the United States and Western Europe in the 1950s and 60s (Hopkins 1). But, the label might be equally well-applied to concurrent literary movements such as the Nouveau Roman, sound and concrete poetry, or, this study argues, New York School poetry. While the visual artists revived key experimental strategies of the historical avant garde (the readymade, grid and monochrome painting, collage, assemblage, and photomontage), the literary movements likewise renewed interest in the earlier experiments of French symbolists and Lettristes, German and Italian sound and concrete poets, and the then less recognized American modernists such as Stein, William, and Stevens.

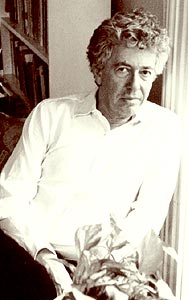

Photo: Kenneth Koch, NYC, 1989, by John Tranter

7

The comically entitled Kenneth Koch: A Tragedy (Koch is, after all, the most insistently silly of all the New York artists) is in part the “cornball modern Vie de Boheme” Rivers imagines above, a drama that simultaneously presents and lightly mocks the New York School “project.” The play is set, appropriately enough, in the Cedar Street Tavern, the famous haunt of the Abstract Expressionists (and the site of Jackson Pollock’s many renowned drunken escapades). Here too Frank O’Hara, John Ashbery, Kenneth Koch, Barbara Guest, and James Schuyler would frequently go to “wr[i]te poems while listening to the painters argue and gossip” as O’Hara records (OCP 512). The play features New York School luminaries such as John Bernard Myers, the flamboyant director of the Tibor de Nagy gallery who published the poets’ first books and was the first to use the label “The Poets of the New York School.” Here is O’Hara and Rivers’ sardonic characterization:

8

JOHN MYERS:

Why, my dear, haven’t you heard? I have a gallery of the liveliest, most original, and above all youngest, painters in America, and for every painter there’s a poet. You know we’ve discovered something called “The Figure” that’s exciting us enormously this season. I don’t quite understand it myself but it has something terribly pertinent to do with the Past. It’s called “Painting Divine” and includes the black laugh of surrealisme and the pile-strewn sobs of suprematism, and lots of boffing. (AND 128)

9

Also present on stage are the major Abstract Expressionists like Franz Kline (who calls Koch “a skinny drink of water . . . a Mountain of Moles, a Matador of Joy. . .” [125]); Willem de Kooning (“Yah, travel is okay, Poland, the marshes, it’s terrific. It’s like the signs I used to paint in Holland when I was a kit” [127]); Elaine de Kooning (“don’t cum dahn on yuh price, Bill, Giedion said youh great” [128]); and a snarling Jackson Pollock who refers to the authors, Frank and Larry, as “those fags,” and ambiguously tells Kenneth, “My wife is a lousy lay, but you’re the worst” (129). Critics like Philip Pavia and Tom Hess also make brief and silly appearances:

10

TOM HESS:

I’ve come to represent the American Renaissance, where is it? (128)

11

And of course the play features the inimitable Kenneth Koch, who is presented (quite accurately) as part intellectual, part clown:

12

KENNETH:

I was a mason, boys. I come from an educated family. Though my grandpa dealt in burlap, my mother wrote up bridge parties for the Cincinnati Courier… The difficulty was in being Jewish. As a high school boy I was very interested in Zionism and changed my name from Cherrytree so I wouldn’t embarrass the Jews. We parked our cars on the hill. The nights were simple. A soda. Thin girls in organdy. Where was the 14th century those evenings?… They called me “queer” and I thought they meant I was a poet, so I became a poet. What if I’d understood them? Moses! what a risk I was running. (128–9)

13

The in-joke at the end of this speech has to do with what O’Hara used to teasingly call Koch’s “H.D.” — homosexual dread — which was, Joe LeSueur observes in his introduction to the Selected Plays, “Kenneth’s understandable dismay at realizing that so many of his friends were gay” (xxiii). Like the Abstract Expressionists, the New York School poets were predominantly a men’s club — but unlike the painters, they were mostly gay men, and their work, like that of Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns, is in part a response to the typical 1950s macho, heterosexist swagger of Abstract Expressionism.

14

Kenneth Koch is, as the proceeding examples show and as O’Hara readily admits, teeming with gossip, name-dropping, and in-jokes:

15

KENNETH:

I wonder if John Myers has persuaded Wystan to make me a Yale Younger Poet yet?… Oh Frank, come away from the Museum of Modern Art, with your baked feet, oh Grace leave Walter… Oh John Ashbery you’ll never be able to afford one, oh Larry Rivers leave fame to the Brachs, oh Bill de Kooning leave the Cedar… oh Jimmy Schuyler why did you beat up Bill Weaver? Bill, forgive him! I am the snow-white Laundry Way. I am the Hand. Or Mouth. There is no intelligence, there is only Europe. (125, 127)

16

As O’Hara’s poetry so frequently reveals, gossip was one of the major currencies of intellectual and artistic exchange in New York in the 1950s and 60s. This was a moment when the gestural and discursive work of “Hand” and “Mouth” were closely linked. The painters, poets, musicians, and critics who gathered at the Cedar and at the equally famous Eighth Street Club (known as “The Club”) were an extremely gregarious bunch, and their art talk, gossip, and debate are a crucial part of the New York School story. While the Abstract Expressionists liked to portray themselves as radical individualists, the history of the New York School shows that art is as much the result of the conversations of a community as it is the activity of solitary producers. New York poet John Giorno has called gossip “the hardcore of art history” and, following the work of critics like Reva Wolf and Gavin Butt, this study will show how the archeology of gossip can reveal important links between the poets’ social and aesthetic concerns.

left to right: James Schuyler, John Ashbery, Kenneth Koch, August 1956

17

Besides the language of gossip, the play also uses and satirizes other predominant forms of New York School poetic discourse. Goldie, a character who is “in love” with Kenneth (the quotation marks signify the campy, theatricalized nature of the emotion), presents his poetry as illustration of the fact that “he’s beautiful in his way” (123). What follows is a burlesque of the New York School’s poetry of surface play, an early mode in their writing which elevates sound over sense, signifier over signified. Here, in the poets’ typically campy way, these avant-garde gestures of fragmentation and discontinuity are fondly exaggerated, almost to the point of absurdity:

18

GOLDIE:

Mother, at night the sea speaks to me with Kochean overtones.

MOTHER:

He may be a spring song to you but he’s a pain in the ass to me. What a beau, he’s an ape.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

GOLDIE:

Listen to this mother:

“We undress orders to Doris

the day tobacco-lift, who

Senator, isn’t that a movie star coughing in your turnip?

O cradle frost, wigged, crane-blown, sign below Kentucky

That the Wettmay be white, dropping alleys on teats.”

That’s the side of him you don’t know.

MOTHER:

Maybe you should marry him, Goldie. (123)

19

The mother’s final line may be delivered ironically or straight since, after all, the above mock-Kochean lines seem no more, and no less, absurd than those the poets were producing at the time in work like “When the Sun Tries to Go On” (Koch), Second Avenue (O’Hara), “Europe” (Ashbery), and Salute (Schuyler).

20

As well as the language of gossip and fragmented surface play, Kenneth Koch also performs what will be discussed in Chapter Four as the language of improvisation or process. The New York School’s “poetics of process” transforms the act of making art or the very processes of awareness (what Ashbery calls in one interview “the experience of experience” [Poulin 245]) into the subject of art. Here, for example, in the play’s second act, Kenneth’s recollection of a recent trip to Europe is delivered in a neo-avant-garde stream of consciousness which again fondly mimics and partly mocks its avant-garde predecessors:

21

The village rats of Chartres. How I long for water where women wash clothes. O soap! sponge! Lysol! fingernails imprisoned in lavender underdrawers, fish, albumen! A lift from Dijon to Nice, a bearded Duke at my knee, guess what he had on his wrist: a thin blue wasp to be suffocated by your tongue… Yes, the past is a hotel where all the rooms are a joy to behold. Why are the Swedish tall? Why are the Belgians interesting? Am I a negro? Is this literature? The lustful play of balding men, eating out their hearts over sandwiches, I am no bigger than their smallest. And is the purpose of life to be mighty in their eyes? Somewhere an egg is cooking. (125, 126)

22

The dadaist exclamations (soap! sponge! Lysol!) and surrealist images of this passage gesture towards a European past through which our character is traveling. However, his journey seems to be devoid of the baggage of oppositional energy and commitment that supposedly fueled much of the art of his avant-garde precursors. The line “The lustful play of balding men, eating out their hearts over sandwiches” (with a nod, perhaps, to the much-reproduced photos of a balding Picasso or Pollock and other large, “lustful men”) highlights one of the New York School poets’ major targets. This target is not only the maverick artist (cigarette or paintbrush in hand, anguished look on face) but more generally the idea of art as overly earnest or overly extended. Unlike predecessors from F.T. Marinetti and André Breton to T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound, and contemporaries such as Charles Olson or Robert Lowell, the New York School poets never wanted to be “mighty in their eyes;” rather, their camp sensibility constantly operated against “mightiness.”

23

As well as performing and parodying the gestures and techniques of the New York School, Kenneth Koch also takes up philosophical questions about the aesthetic roots and commitments of the School. These questions are put, somewhat humourously, into the mouth of painter Milton Resnick:

24

Tradition, it’s like a brick wall, you build it up, it gets higher and heavier every century but yuh keep going because yuh think there is plenty of room, and then it falls over on yuh… You know what the New York School is? It’s a lot of guys who know all about bricks. It’s us… We’re pushin em down day and night. It’s a cold water loft revolution. Take that Brooks Brothers look off your face. Put on these dungarees. Elaine broke em in herself. (131)

25

As with so much New York School poetry, there is both comedy and consideration in this passage. If Tradition is a brick wall, and the New York School set out, in good avant-garde fashion, to push it down, what did they erect in its place? Perhaps more to the point is the question of whether the wall can ever really be knocked down, or whether its bricks can only be disassembled, re-fired, and re-layed.

26

“Pushin down” bricks can be read in two ways: one of the brick-layer who builds a wall, and the other of the renegade who wants to demolish it. Although the “historical” avant-garde (of the first decades of the century) and some neo-avant-garde movements of the 1950s and 60s have claimed the role of wall-smashing iconoclasts, this study plans to look more closely at the substance and meaning of this claim, particularly for the “cold water loft revolution” of the 1950s.

27

The humour and absurdity of Resnick’s comments indicate O’Hara’s and Rivers’ ambivalence to the virile, knock-em-down avant-gardism of not only the Abstract Expressionists but also another group of “cold water loft” revolutionaries in New York, the Beats. If such radical activity means only wiping “that Brooks Brothers look off your face” and “put[ting] on these dungarees” (as corporate advertisers and the culture industry in the 1960s tried to convince innumerable consumers to do), then it doesn’t signify much for advanced artistic practice. What kind of barriers the New York School poets were facing, how they responded to the walls of the past and the present, and what, ultimately, they did with the bricks will be the subjects of the following chapters.

28

Chapter One begins with the question of classification. It considers the New York School’s place in the landscape of postwar American poetry and, more broadly, in realm of the so-called avant-garde and neo-avant-garde. Surveying some of the key historical and theoretical writings on the avant-garde, the chapter ends by focusing not on the fashionable theme of the avant-garde’s death but rather on the space it opened for future artists. For the New York School, this is a space closely linked to that slippery term “indifference.” It is both a place and a pause, a gap between the increasingly old-fashioned antagonism of “radical art” and the cooly nihilistic acquiescence of “radical chic.”

29

Chapter Two turns to the question of neo-avant-garde ideology by reading three New York School “manifestoes” in order to better understand the aesthetics and politics of indifference. Chapter Three considers the New York School’s relation to other arts, particularly painting, through an examination of the “poetics of process.” Process art is examined as a neo-avant-garde strategy for working in the “gap between art and life” (as Rauschenberg once put it). Here I offer a reformulation of Peter Bürger’s problematic centerpiece in his Theory of the Avant Garde, that is the revolutionary goal of the reintegration of art and life.

30

In Chapter Four the question of taste is considered by examining the New York School’s use of camp to deconstruct the high/ low, avant-garde/ kitsch binary so essential to modernist culture. Here we examine how campy combinations of experimental and popular forms become another way for the New York School poets to create a non-oppositional, neo-avant-garde position.

31

A conclusion reassesses the neo-avant-garde move “beyond radical art” and considers where such a repositioning leaves the poetry. Rather than in the discouragingly nihilistic cycle of avant-garde challenge and recuperation (that Paul Mann imagines is the inevitable fate of the ever-dying avant-garde in his The Theory-Death of the Avant-Garde), this book ends with a more optimistic assessment of the possibilities of a postmodern or “neo” avant-garde. It suggests that there may be a space beyond “radical art” — and its favourite gestures of antagonism, individualism, and futurism — for a different avant-garde which follows a presentist, processual, and apparitional (rather than oppositional) aesthetic.

Mark Silverberg

Mark Silverberg is Associate Professor of English at Cape Breton University in Sydney, Nova Scotia. His essays on twentieth century literature and culture have appeared in journals such as Contemporary Literature, English Studies in Canada, Literary Imagination, Arizona Quarterly, and Essays on Canadian Writing.