| Jacket 40 — Late 2010 | Jacket 40 Contents | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 20 printed pages long.

It is copyright © Francisco Aragón and the Estate of the late Gerardo Diego and Jacket magazine 2010.

See our [»»] Copyright notice.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/40/diego-by-aragon.shtml

Gerardo Diego

With ten poems from Handbook of Foams

translated from the Spanish by Francisco Aragón:

Hotel / Emigrant / Goodbye / Clouds / Autumn / Twelfth Night / Panorama / Allegory / Window / Recital /

1

(July 1925)

Dear Poet

I received your nice letter shortly after you posted it. You have nothing to thank me for. We have you to thank since we were able to award a beautiful book. It’s a shame you didn’t enter Handbook of Foams… Marvelous your Handbook of Foams. In my judgement, the highest achievement of the new lyric.

See you soon. Yours

Antonio Machado [1]

2

Gerardo Diego (1896–1987) was born in the north of Spain in Santander, the capital of Cantabria — a region which, along with Galicia, the Basque Country and Asturias make up what’s often called la España verde for its lush landscapes. Although Diego spent most of his professional life in Madrid, his works often engage the seascapes of the north, including his critically acclaimed volume, Handbook of Foams. The translations that follow are from this thirty-poem suite, or “concerto” as one scholar has called it. [2] Diego, in addition to being a poet, was an accomplished pianist and music critic. Music and the sea are motifs that insinuate themselves throughout Handbook — all under the banner of what literary critics came to call creacionismo, whose most well-known adherent was the Chilean poet Vicente Huidobro (1893–1948). Octavio Paz (1914–1998) once said of him: “He is everywhere and nowhere. He is the invisible oxygen of our poetry.” [3]

3

1916 is a dual threshold of sorts for poetry in the Spanish language. On the one hand, Rubén Darío (1867–1916), the master of modernismo, abandons Europe to return to his native Nicaragua and dies, marking the decline of this symbolist aesthetic. On the other, a young Vicente Huidobro departs from Santiago, Chile for Paris, France to absorb the artistic innovations percolating there, intent on becoming one of its most flamboyant ambassadors.

4

But first he stops in Madrid, where he meets Rafael Cansinos-Asséns (1882–1964), who introduces him to Ramón Gómez de la Serna (1888–1963): they are, these two, the overseers of what’s new in Spanish letters — friendly rivals who hold court at their respective tertulias at Café Colonial and Café Pombo. But Huidobro decides to keep to himself certain notions. Had he felt more secure, he might have shared the gist of a talk he gave in Chile two years prior, in which he stated:

5

We’ve accepted, without giving it much thought, that there can’t be other realities except those that surround us, and we haven’t stopped to think that we too can create realities in a world of our own, a world that is waiting for its own flora and fauna. [4]

6

Huidobro’s tentative ideas around what he terms creacionismo are solidified by the time he reappears in Madrid in 1918 after his two year stint in Paris — a stint during which he meets and mingles with the likes of Apollinaire, Pierre Reverdy, Pablo Picasso, and Juan Gris. [5] He sets up a literary salon at his home on Plaza Oriente opposite the Royal Palace. The frequent gatherings take place from August to November. Huidobro’s residence in Madrid becomes the place to be if you want to learn and sample what’s new in the arts. In his book on Apollinaire, Spanish avant-garde poet and critic Guillermo de Torre recalls:

7

Where did I hear of him, or read him for the first time?… I don’t think I would be mistaken if I said it was at Vicente Huidobro’s house. [6]

8

During these months in Madrid, Huidobro manages the feat of publishing four collections of poetry, including Arctic Poems, which Antonio Machado reviews in a piece titled “Images in the lyric (on the margins of Vicente Huidobro’s book).” Gerardo Diego doesn’t meet the Chilean poet during this period but he does read Machado’s review with great interest. [7] Of Huidobro’s stay, the aforementioned Cansinos-Asséns wrote:

9

… his arrival in Madrid was the only literary happening of the year, because with him the latest literary tendencies from abroad came our way; and he assumed the representation of one of them, not the least interesting, creacionismo.… [8]

10

1919 marks Gerardo Diego’s decisive trip Madrid, not to meet Vicente Huidobro yet but rather to immerse himself in Huidobro’s wake: ultraísmo, Spain’s branch of the Eureopean avant-garde. Diego will recall in 1948:

11

A few months later, and as a result of his visit, ultraísmo was born, and the fuss that was being made in Spain was unleashed. Controversies, lectures, magazines, books, articles, manifestos… [9]

12

Ultraísmo, more than offering a specific literary model, creates the ambiance Gerardo Diego intuitively needs, at least for a time, to point him in new directions. Through friends, he gets to meet (like Huidobro before him) Rafael Cansinos-Asséns, which of course leads to further contacts. At Cansino-Asséns’ tertulia, for example, he encounters a young Argentinean named Jorge Luis Borges, with whom he will share the Cervantes Prize, Spanish letters’ highest honor, in 1979. And he also meets a poet from Granada named Federico García Lorca. One self-proclaimed ultraísta, Eugenio Montes [10] — who will eventually review Handbook of Foams in the prestigious journal Revista de Occidente — loans Diego a copy of Arctic Poems, from which he copies out three he especially likes, including one titled “Moon.”

13

When Gerardo Diego heads back to Santander he takes a short detour to Bilbao to see the poet, Juan Larrea. In addition to the three hand-copied poems, Diego is carrying the magazines Grecia and Cervantes, harboring the hunch that these will impress his Basque friend. At a symposium on Huidobro that will take place in Chicago in 1978, Larrea will recall what “Moon” meant to him, saying, “its reading plunged me into an atmosphere of ultraworld…” He will sum up the materials Diego brought to Bilbao by saying, “The novelty impressed me in such a way that from that day on I began to feel like another person.” [11]

14

Dámaso Alonso, the most scholarly poet of Diego’s generation (commonly known as the generation of ’27), and who went on to preside over the Royal Spanish Academy many years later, would write that although ultraísmo, as a movement, did not produce great poets, modern Spanish poetry could not be fully understood without taking ultraísmo into account. The only books that survived, in Alonso’s view, were two: Image and Handbook of Foams, both by Gerardo Diego. These collections were the result, though only in part, of Diego’s contact with ultraísmo and its challenge to “go beyond.” Diego says:

15

I invented my own ultraísmo in Santander. I began to write poems in a somewhat systematic way in 1918 and I alternated very naïve poems… with others that were more adventurous, which I’d write for pleasure and without restrictions, not trying to penetrate the secret of the classics, but rather, on the contrary, trying to discover poetry’s new worlds. (Bernal 14)

16

More than the literary politics and posturing playing out in Madrid, Diego’s primary field of exploration is Vicente Huidobro’s poetry and his correspondence with Juan Larrea.

17

Towards the end of 1919 Gerardo Diego delivers two lectures in Santander. “The New Poetry” is about the isms flaring around Europe, and “Poetic and Artistic Renovation” presents Spain’s ultraísmo. Both make more than a few waves, spurring debate in favor and against the new trends taking shape. But Diego doesn’t consider himself a militant in the classical sense. One specialist sees his association with the ultraistas as only one part of his “poetic biography:”

18

In truth, Diego, despite his ultraist posture, or in addition to it, irreversibly consolidates throughout 1921 a process that was initiated in 1919 and which, in theory and practice, was kept afloat by Larrea; which consisted in a personal apprehension and assimilation of Huidobro’s creacionismo, whose books he devoured and commented with his close Basque friend (Bernal 41)

19

Diego finally decides to write to Huidobro in 1920, sending him a copy of one of his essays and an extensive poem dedicated to him titled “Gesta,” which will form part of Image, his first avant-garde book. But here’s the thing: even before Gerardo Diego mails these materials to Vicente Huidobro, the Chilean has already heard of him. It’s a time when everyone is writing to Huidobro and in the letters he receives from Madrid a “creacionista” (not ultríasta) named Gerardo Diego is sometimes mentioned. Huidobro’s curiosity is piqued and he asks a Spanish friend to send him a few of Diego’s poems. [12]

20

In April of the following year, 1921, Madrid’s newsstands are displaying the first issue of Creación, an art magazine edited by Huidobro from Paris. In it there is a poem by Diego titled “Cold,” a poem Huidobro will cite in his extensive prose piece, “Creacionismo,” which will be published in his book, Manifiestos, in 1925.

21

To set the record straight, then: creacionismo was not a one-man school, as two of Vicente Huidobro’s translators into English, both American, have written. In fact, in a 1923 interview for the Paris journal L’Esprit Nouveau, Huidobro himself mentions “the creationist poets Juan Larrea and Gerardo Diego, two great poets.” One Hispanist has referred to Huidobro, Diego and Larrea as “the creationist triad.” [13]

22

In the Autumn of 1921, Huidobro writes to Diego, expressing his wish to give a talk in Madrid on creacionismo. Diego confers with a friend on the board of the Antheneum and a date is set for December. Both Diego and Larrea are finally going to meet who they consider their mentor. Larrea is living in Madrid working at the National Historic Archive while Diego, teaching high school French in Soria, will travel to the capital by train. They attend Huidobros’s lecture and notice that the ultraístas give the Chilean a cool reception. This is due, in part, to the dispute over who was the “founder” of creacionismo: Pierre Reverdy or Vicente Huidobro? Reverdy’s camp is spearheaded by the ultraístas’ most militant activist, Guillermo de Torre, [14] who will publish his important study, European Avant-Garde Literatures in 1925, the year that Handbook of Foams finds its way into print.

23

Diego remains in Madrid for only a day, so it’s Larrea who gets to talk at length with Huidobro. The author of Handbook of Foams will have his chance when he’s invited to Paris.

24

In late summer/early Autumn of the following year Gerardo Diego spends sixteen days in the French capital. There are two letters addressed to Larrea — one dated September 5, 1922 from Paris and the other October 7, 1922 from Gijón — that scholars have scrutinized to better understand the context from which Handbook of Foams emerged. [15]

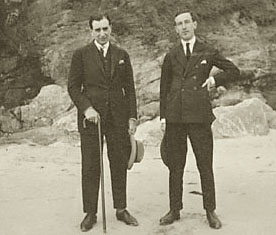

l to r: Vicente Huidobro, Gerardo Diego

25

Although relatively brief, the letter from Paris touches upon key elements of Handbook’s origins: Vicente Huidobro’s work, Juan Gris’ cubism, and music. Other information is incidental: Diego departed for Paris from San Sebastian on August 31; Huidobro was waiting for him at the train station; the weather was bad, dissuading them from any sight-seeing. A more interesting observation is that Huidobro seems to know everybody. They have a couple of meals with Juan Gris and visit his studio, and he mentions that they are set to have lunch with Erik Satie and Maurice Raynal, an art critic associated with the cubists.

26

The letter from Gijón is considerably more substantial. In reference to the attitude in Paris, at least Huidobro’s, towards musicians, Diego writes:

27

They look down on musicians as primitives — we’ve discussed this quite a bit, Huidobro can’t conceive that I like music — only Erik Satie, Auric, and a few others are partially saved…

28

On Juan Gris he writes:

29

We found him working in his studio. He showed me his things and from that day on we had lunch together often and we had long talks. He’s an admirable [ ] conscientious artist who judges universal art and his own work with a clarity that is mathematical… Listening to him speak of aesthetics, I have learned to catch a glimpse of what painting is, and in this sense I do understand his work, that is: it produces in me an impression of sober and delicate beauty, of mature and reposed construction…

30

Gerardo Diego will go on to dedicate the longest poem in Handbook of Foams, “River Song,” to Juan Gris. Nineteen ninety-six marks the centenary of Diego’s birth and the long-standing journal, Revista de Occidente, publishes a special number titled “Gerardo Diego and the invention of new poetry”, which includes an article titled “Gerardo Diego’s cubist fascination.” [16] The article discusses the correlation between Gris’ paintings and Diego’s verse, above all in Handbook.

31

On Huidobro’s poetics Diego writes:

32

This plastic technique in Huidobro’s poetry has shed much light on his work, though I wouldn’t know how to specify with precision the “why” but could only tell you about it in general terms. The principal of the rapport is the hub of it… It’s the same thing we saw in him in Madrid, but it’s clearer to me now after seeing cubism. Nothing can go without its “why” and the artist should know at all times the values of the measures and elements he employs… [17]

33

Diego has said it on more than one occasion: Huidobro’s creationist work has cubist painting as its model, while his own avant-garde verse, in addition to cubism, adds music as a guiding star. This particular excerpt lends weight to the notion that Diego’s innovative work is not surrealist: it clearly rejects the idea of “automatic writing.” Diego continues:

34

I saw at the Opera Boris Godunof, Moussorgsky’s famous opera. Music that is purely musical has never moved me with such intensity, like certain passages that were virtually paradisical. I almost wept with joy, not with melancholy or enthusiasm, which is how I usually get drunk with music.

35

In one of his notes, [18] Diego specialist José Luis Bernal writes: “This letter offers, as well, a very interesting piece of data about Diego’s musical preferences in contrast with pictorial cubism’s rigid tastes, which is key for a correct reading of Handbook of Foams, the true fruit of that experience.” Diego will point out many years later the importance of his musical background in this book’s elaboration. [19]

36

Before citing a final fragment from this letter, I would like to call attention to something written by the late José Hierro, arguably the Spanish poet most influenced by Gerardo Diego:

37

Creacionismo would be a way out for a classical disposition, bashful with its feelings, incapable therefore, of expressing itself with the blind, romantic, immodesty of surrealism. But Gerardo Diego’s great contribution, what distinguishes him from the others, is that despite appearances, his creacionismo is not an experience that is more or less amusing and ingenious, but rather a form — irrationalist — of confession. [20]

38

Gerardo Diego, in commenting on his Handbook, says: “It’s possible that these poems, to the reader, seem cold, but I remember very well the blood they cost me.” [21] With all this in mind, the final excerpt from Diego’s letter of October 7, 1922 seems to suggests the poet’s mood, or point of departure, in at least a handful of the poems in this collection:

39

This summer’s great sentimental failure marked me more than I thought; thankfully this trip has been a purification. But now, in the obligatory solitude of this indifferent, hard-working, cheery, superficial city, pessimistic and misanthropic thoughts, when not of a lower nature, assault me. I’m convinced I’m an ill-bred child and that without any luck, my life will be empty and miserable. It’s been 20 days with no sign of friendship or love. If this doesn’t change soon, I think I’ll emigrate. Meanwhile, and filled with resignation, I read novels and go to the movies: two absurdities.

40

Diego has just turned 26. With the exception of “Spring” — which opens Manual de espumas — he is about to write, under a melancholic spell perhaps, the twenty-nine poems that will complete the collection that concerns us. That summer Diego is living in a beach bungalow in the coastal city of Gijón in Asturias, from which he is able to glimpse the Cantabrian sea.

Gerardo Diego

in later life

41

Towards the end of the letter he says: “I haven’t written anything new.” Juan Larrea, his dear friend and fellow creationista, would have been the first to know if he had.

42

Nearly two months later, in a letter to another close friend, José María de Cossío, author of the classic encyclopedia on bullfighting, Gerardo Diego reveals: “I’ve just put the finishing touches on a new creature that aspires to be a book of poems, born Handbook of Foams.” [22]

[1] This letter was reproduced in a special homage issue of Punta Europa #112–113, Madrid, in “Tres Cartas a Gerardo Diego”. Antonio Machado is referring to the National Poetry Prize, which Gerardo Diego won that year with a manuscript of traditional verse titled Poemas Humanos. He did not enter Handbook of Foams because it did not have the minimum number of required pages.

[2] The scholar in question is José Luis Bernal, whose edited volume, Gerardo Diego y la Vanguardia Hispánica (Universidad de Extremadura, 1993) was a key source for this piece.

[3] Cited in “Poetry is a Heavenly Crime,” David M. Guss’ Introduction to The Selected Poetry of Vicente Huidobro (New Directions, New York, 1981).

[4] Huidobro’s “Manifiesto non serviam,” cited in “Teoría del Creacionismo” by Antonio de Undurraga, which prologues Poesía y Prosa (Aguilar, 1957).

[5] For Huidobro’s exploits in Paris, David M. Guss is a place to start. From there, René de Costa’s book, Huidobro: The Careers of a Poet (Oxford University Press, 1984), is a thorough study and account.

[6] He also affirms that it was at Huidobro’s house that ultraísmo, Spain’s avant-garde movement of the period, was “incubated.” Apollinaire y las teorías del cubismo (EDHASA, Barcelona, 1967).

[7] René de Costa’s paper, “Posibilidades Creacionistas,” is a primary source for much of this. It can be found in the aforementioned Gerardo Diego y la Vanguardia Hispánica, 1993.

[8] “Un Gran Poeta Chileno: Vicente Huidobro y el Creacionismo” (1919) by Rafael Cansinos-Asséns, included in Vicente Huidobro y el Creacionismo edited by René de Costa (Taurus Ediciones, Madrid, 1975).

[9] The first exhibition devoted entirely to ultraísmo was held in Valencia, Spain, between June and September of 1996 under the organization of Juan Manuel Bonet, a specialist in the movement who prepared the text and notes for the handsome catalogue, which included a complete English translation. El Ultraísmo y las artes plásticas, Centro Julio González 27 Junio — 8 Septiembre.

[10] Montes would later abandon the ultraist aesthetic, and adopt fascist politics.

[11] La Biografía Ultraísta de Gerardo Diego by José Luis Bernal (Universidad de Extremadura, Cáceres, 1987). This 60-page study is another primary source for much of this. This citation is taken from the article “Vicente Huidobro en Vanguardia” in Revista Iberoamericana, v. XLV #106–107, 1979. Further citations from this study are indicated in the text in parenthesis, i.e. (Bernal 41).

[12] See note 7 above.

[13] Robert Guerney, in “El Creacionismo de Juan Larrea,” is the Hispanist in question, in Gerardo Diego y la Vanguardia Hispánica, 1993. David Bary, in his book Nuevos Estudios sobre Huidobro y Larrea (Pre-textos, Valencia, 1984) cites the interview in issue #18 of L’Esprit Nouveau, in which Huidobro names Larrea and Diego as creacionistas.

[14] Many years later, Guillermo de Torre writes that his position on Huidobro had to do with his youthful activism and his way of countering Huidobro’s ego, which even his friends admitted was considerable. In fact, in 1962, he writes an article — “La Polémica del Creacionismo: Huidobro y Reverdy,” included in Vicente Huidobro y el Creacionismo (Taurus) — in which he persuasively argues that neither Huidobro nor Reverdy had a monopoly on their avant-garde poetic; painters and writers of the period were saying more or less the same thing: that the artist had to create a new reality and not describe or imitate the reality before them….

[15] “Desteñidas Esquelas. Charlas Líricas. Algunas cartas de Gerardo Diego a Juan Larrea” commented by José Luis Bernal and Juan Manuel Díaz de Guereñu, Insula #586, 1995.

[16] Revista de Occidente #178 Marzo, 1996, a special issue titled “Gerardo Diego y la invención de la poesía nueva” The article’s author is Teresa Hernández.

[17] Just before citing a brief fragment of Huidobro’s lecture in Madrid in 1921, René de Costa writes: “In this way, Huidobro constructs a text which forces the reader to associate ideas and establish the lexical contacts which make the metaphors detonate, creating a new and sparkling language in the process, a new way of poeticizing.” The fragment: “The poet makes things in nature change their lifestyle, retrieving with his net everything that moves in the chaos of the unnamable, hanging electric wires between words, remote spaces suddenly lighting up… ” Vicente Huidobro: Poesía y poética (1911–1948), Antología comentada por René de Costa (Alianza, Madrid, 1996).

[18] See note 15.

[19] In “De la musique avant toute chose: la evolución del pentagrama en la poesía de Gerardo Diego,” Gabriele Morelli writes: “The process in which the phonic effects require a substantial structural value in the message, to the point of representing the very reality of the poetic discourse, is carried out completely in the creationist experience of Handbook of Foams.”

[20] “Entrañable Gerardo” by José Hierro in a special homage issue of Punta Europa # 112–13, Madrid, 1966.

[21] Ricardo Gullón cites this statement of Diego’s in “La Veta Aventurera de Gerardo Diego” in Insula #90, 1953.

[22] Gerardo Diego / José María de Cossío. Epistolario. Nuevas Claves de la Generación del 27 Edición de Rafael Gómez de Tudanca (Ediciones de la Universidad de Alcalá de Henares, 1996).

Gerardo Diego

Gerardo Diego (1896–1987) is perhaps the least known poet, outside of Spain, of the renowned “generation of ’27,” which included Federico García Lorca, Rafael Albertí, Pedro Salinas, Jorge Guillén and Luis Cernuda, to name a few. With the exception of Lorca, who was executed at the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, and Diego, who remained in Spain, these others went into exile, which may explain, in part, why Diego is less known. Another factor may have been his compliance, as a devout Catholic, with the Franco dictatorship. And yet before the war Diego was among the most active of his cohort, having the foresight and taste to edit the groundbreaking and prophetic Spanish Poetry Anthology 1915–1931, in which he gathers this generation of poets for the first time, as well as this generation’s immediate mentors. He was also among the most fervent of his group to explore and embrace the avant-garde tendencies of his time, particularly creacionismo, which he alternates throughout his writing career with more traditional verse forms, making him unique among his generation. He also edited two journals: Carmen: a little magazine of Spanish poetry, and Lola: Carmen’s friend and supplement. Over the course of his career, his many books won all the major poetry prizes in Spain and he shared the Cervantes Prize with Jorge Luis Borges in 1979. An accomplished pianist and music critic, his day job throughout his professional life was as a high school French teacher. The last project to occupy Diego was the preparation of his two-volume Poetry. He completed the task, but his death on the afternoon of July 8, 1987, a month short of his 91st birthday, prevented him from holding the handsome hefty volumes, which finally appeared in 1989. In 1996, on the occasion of the Centernary of his birth, various acts and exhibitions were organized, among them one at the National Library in Madrid titled Gerardo Diego and Spanish Poetry in the 20th Century.

Francisco Aragón

Francisco Aragón’s credits as a translator (from the Spanish) include the books, Sonnets to Madness and Other Misfortunes (Creative Arts Book Company), Of Dark Love (Moving Parts Press), Body In Flames (Chronicle Books), and a selection in From the Other Side of Night (University of Arizona Press) — all by Francisco X. Alarcón. He also collaborated, in the early nineties, on Federico García Lorca: Collected Poems (Farar, Straus & Giroux) and Lorca: Selected Verse (Farrar, Straus & Giroux). His journal and chapbook publications, as a translator from the Spanish, include Achiote Seeds, Chain, Chelsea, Luna, Nimrod, The Packing House Review, Quarry West, and ZYZZYVA. A native of San Francisco and former long-time resident of Spain, he holds degrees in Spanish from UC Berkeley and New York University, respectively. Francisco Aragón is the director of Letras Latinas, the literary program of the Institute for Latino Studies at the University of Notre Dame. For more information, visit: http://franciscoaragon.net

Ten translations from Handbook of Foams, from the Spanish of Gerardo Diego (1896–1987), translated by Francisco Aragón

Hotel

for Alfonso Reyes

His head without a wreath or hat

and his heart’s the color in vogue

With every new dance

the clock loses a beat

showing the wrong hour

The wind blows from your cloak

caressing

the tango’s plucked fruit

Harvest of crushed clouds

and beloved modes of music

And the rhythm of sighs

makes the couples twirl

luring the lobby closer

Tightly shutting my eyes

I picture voyages

hotels anchoring the old keel

They’re islands like ocean liners

growing masts

abundant with winter fruit

where consumptives breathe

the tender oxygen

Upon hoisting the flag aromas

of wood are dispersed in the air

with the feathers of hunted birds

Autumn shrivels ties and hats

and from the carpet blooms spring

Roulette of chance and the seasons

Fashion’s jockeys raffle their colors

And whoever loses the bet

gets to waltz with a new lover

I love hotels and good weather

and I’ve seen women with roasted curls

The waves spraying them with cocktail foam

Emigrant

The wind always returns

though each time brings a different color

And local children dance

around new kites

Sing kite sing

with your wings spread wide

and hurl yourself in flight

though never forget your braids

The kites came and went

yet their shadows still hang on doors

and the trails they left behind

fertilize the fields

In the furrows of the sea

not a single seed fails to sprout

Flattened by the winds and boats

the foams reflower each year

But I prefer the hills

that carry on their agile backs

the stars expelled from their harem

Shepherd of the sea

who without rein or bridle

guides the waves to their fate

Don’t leave me sitting beside the road

The wind always returns

The kites too

Drops of blood fall from their braids

And I get on the train

Goodbye

Forgotten by the rain

my fingers’ll wither one day

My rumpled hair

won’t sprout flowers anymore

nor will the moon descend

placing its crown on my hat

And from tomorrow on

the sun won’t sit with the sick

Woman

fragrant laundress

in the wine-drenched dusk

who’s etched and etched on the moon

nuptial emblems —

stitched my initials on a flap of the sea

Woman

When you drift slowly from your very life

we’ll see the sun come down

and the rotting fruit drop

And as you sip your laughter

my accordion will baa

searching in the shrubs

the rhythms of your heart

Crickets will count your tiny steps

Nor will the moon grow full

even if you say

I love you

nor will the snow flutter down

blessing my hat

Clouds

for Eugenio d’Ors

I shepherd on the boulevard

would unleash benches

and seated on the lip of the promenade

release the lambs to roam

Everything had ground to a stop

My notebook

the only winter frond

newsstands anchored firmly in the foam

I’d think of the aimless beds forever fresh

where I smoked my poems and counted stars

I’d think of my clouds

the sky’s warm waves

searching for a home without ceasing to fly

I’d think of the lovely morning’s pleats

like ironing my handkerchief unfolding it

But in order to soar

the sun needs to swing

and our heavenly globe revolve in our hands

Things are different now

My dancing heart deceives the stars

and the fever the electricity are such

a bottle incandescently shines

Not even the wild tower turning slowly

distributes the winds

nor do my fingers milk the bowl-like hours

We have to wait for the marching

storms and prophecies

We have to wait for the moon to birth

the messiah bird

Everything has to arrive

The cinema’s surf is the same as the sea’s

Distant days flash across the screen

Flags never seen before perfume space

and echoes of war crackle on the phone

The waves swell around the world

No explorers left for poles and straits

and tourists are dying

of an unknown disease

guidebooks spread on their chests

The waves swell around the world

I’d love to ride along

They’ve seen it all

They never look back or return —

evicted pillows sandals of Christ

Let me lie here till the end of time

I’ll smoke my poems and lead my clouds

down every road on earth and in the sky

And when the sun returns on its white horse

my bed poised will lift off and fly

Autumn

for J. Chabas y Martí

Woman thick with hours

and yellow with fruit

like yesterday’s sun

The clock of the winds saw you flower

while in its ancient cage

the stubborn afternoon yanked its feathers

The clock of the winds

alarm of Easter birds

that’s rounded the world

spouting Advent’s waters

From your eyes flows sand a barren river

And so many distracted butterflies

have perished in your gaze

stars no longer shed their light

Woman cultivating

seeds and dawns

Woman from whom bees come forth

who forge the hours

Woman punctual as the full moon

Part your tresses origin of the winds

For empty and unfurnished

my hive awaits you

Twelfth Night

for J. Díaz Fernandez

The boy and the mill

have forgotten their only refrain

The wheel’s fallen silent at E flat

around the well

where water rises and the sun goes down

A hand on their cheeks

the chimneys think one day they’ll fly

The moon won’t arrive today

nor will the drunk stumble

past the open door and lullaby

Here at the foot of the wall

tired from the trip

the wind has taken a seat

The devoted policeman jots

new stars down in his pad

And failing to cross these streets

the river carts

toss their heads in vain

Only the weather cocks sing their song

The gloomy houses

comb their roofs

And one of them is dying

and no one is noticing

The moon’s not coming tonight

nor does the streetlamp cradle the drunk

Panorama

The sky’s done up with crayons

My spotless jacket hasn’t gazed upon love

And arcing from the gardener’s hands

rainbows water the outdoor shrubs

A lost bird nests in my hat

The paired-off lovers wear down the parquet

And you barely hear God’s instructions

playing chess with himself

Children sing for April

Green and rosy clouds reach the finish

I’ve seen flowers emerge

from between the pages on a music stand

and the hidden hunter kill a kite

Summer rehearses on its new stage

and in a corner of the countryside

the rain is playing the piano

Allegory

Here I am trampling my lines

like the boat of the afternoon

leaving in its wake a trail of blood

Stay away don’t listen to me

Winners of bread

and love’s liquer

The last performer’s just collapsed

holding in his hand the natural flower

Beauty without a wage

My summer violin’s

classical beauty

Birds learn the measure of my art

and the rain tunes its rusty guitar

Days go by dancing

Each one fashions a new shape

And don’t you believe this a game

It’s smoke free verse

or the sea renewing itself

My key unlocks the suits

extracts their inner flesh

Heart of the dress

Cloakroom and poetry and no pain

Window

for José Bergamín

The curtain opens to a violin

The window hangs from a nail

The countryside is still concealed

The sun cylinder of oxygen

keeps the painting pristine

and the glazing’s done by the rain

This house is alive

Twice in one minute

the window breathes

And from my hands rise

plumes of votive smoke

The painting on the wall dies every year

I am autumn’s pianist

I open and close the night like a book

and play the music in

my handmade sky

You can choose

The time and the door

But once you’ve loved you have to die

Once more the wind has left my pages white

So again I begin

Don’t scan the ceiling for fatherly planets

Recital

At night the sea returns to my room

and the freshest waves die on my sheets

No one can doubt

the angel poised for flight

nor the spout of water heart of the Pianola

A butterfly flits out of the mirror

and in the light beaming from the daily paper

I don’t feel old

Under my bed

flows a river

and on the pillowed sea

the hollow shell has stopped singing