| Jacket 40 — Late 2010 | Jacket 40 Contents | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 23 printed pages long.

It is copyright © Ariel Goldberg and Jacket magazine 2010. See our [»»] Copyright notice.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/40/goldberg-photography.shtml

I

1

It is our historic responsibility not only to produce photos, but to make them speak.

— Ariella Azoullay, The Civil Contract of Photography [1]

2

To define the news is an insatiable practice: the industry churns inescapably; the banality nudges against tales of atrocity; the public space gets mangled in its private receptions.

3

I am fixated on the still photograph in the news, meaning someone was sent to take it or already there to take it. Like finding the part in a thick head of hair, I am separating this photograph from the advertisement, which bombards the majority of the spreads, blinks around borders to tease visibility in overlapping windows.

4

The locus of this fixation is on print editions of newspapers because photographs in this form symbolically linger — they don’t get refreshed (albeit discarded unless hoarded) and are at a hand’s reach as opposed to a screen’s glare.

5

In obsolescent definitions, to recognize is to look over again. In current definitions, to recognize is to mark something as entitled to consideration. [2] The act of recognition, as photographs are increasingly taking up real estate in newsprint, is a time commitment to disturbance.

6

Words in the news lend themselves to becoming part of this definition of images when taken as a whole, read quickly or not read at all. Much newspaper surfaces as template or ready made in visual art. Part of the complication is as much as this is a collection of stories with untrustworthy narrations, this newspaper is an aesthetic object.

7

Looking at photographs in the news carries with it the weight of questions that become (en)listed even after looking at just one photograph. Looking at photographs in the news, for me, is a barrage of questions about origin stories built on murky and cacophonous uncertainties. These questions articulate themselves against a backdrop of rushing through a dark path and not knowing where you are going and how long it will take to get there.

8

These questions are how photographs speak on their own, and they do powerfully, as interlocutors trapped in another time/space than their viewer/reader. Our attempts to make photographs speak vacillate between subordinate and intrusive.

9

Carrying these questions of photographs around is as heavy as carrying camera equipment. Asking these questions is like insisting your film be hand checked by the Transportation Security Administration. Attempting to answer these questions is as full of computations that reveal bad math because in this scenario you’re not even traveling through the air to places to leave them behind — and if you were, you most likely would have been shooting digitally with nothing for airport employees to wave papers over your equipment that could detect traces of dangerous ingredients. Or say you’re safe to pass through.

10

The standard one line caption underneath a photograph is a limping flag of context. A Caption Poetics is not about the maintenance of fact or truth.

11

After I look at a photograph in the news my eyes move on to subsequent acts of looking in and around it. I start to adjust the details of the “real” caption, cooking and burning what I remember. These are photographs that dodge the question of ownership.

12

It is possible to look at any photograph in the daily visual stream and recognize I will look at it forever. Then the question arises of looking at a photograph forever as opposed to not forgetting a photograph.

13

The sense of ownership, literalized through such actions as a cut out section from the paper, a link sent to a friend, a pause, frees the transport and exchange of the image’s new mindset of replica.

14

To gain clarity is devalued in this atmosphere of defining news because I am writing under the presumption that before we receive information there are so many acts of cropping in the production of news that I can barely re-imagine them. This recognition of the crop on top of crop is entirely separate from trying to converse with the interlocutors embedded in the photographs’ questions. Thus the beckoning cacophony.

15

There is also the cropping done under the light of an enlarger in the darkroom. As a young photographer, I held close the advice of avoiding interference with the original frame. The framing is one body moving in a space. Zoom lenses distort exposure. Arguments still air out on Robert Capa’s famous statement that pictures will be good enough whether or not you are close enough.

16

Cropping during an enlarger’s exposure onto light sensitive paper in the dark is considered advanced and only necessary for certain situations. One of those situations is the directed self-portrait. Another is when you have little control. [3]

17

Photography would have died by now if it were a person. But the medium keeps reinventing itself. The time you have to wait to see what you took is shrinking. The readiness of cameras is exponentially multiplying throughout the mundane accumulation of unprinted archives.

18

Cameras are shoving their hands in pockets.

19

To have a glimpse at vast ways to tell a story and retell it I can engulf in or flash through multiple news sources. I can also see who bought the same story or who excluded a story.

20

Pictures are no longer radical by virtue of their construction or their form, but rather by virtue of their numbers, their mass.

— Andreas Spiegl, Radical Images: Austrian Triennial of Photography [4]

21

People using shutter buttons who then increase awareness about urgent social issues — issues like torture that rely, initially, on the public’s right to know — don’t need to be traced to staffs of newspapers or documentary photographers hired by the government as they were during the times of the Works Progress Administration. Now the government has to pay for lawyers to defend their service women and men whose cameras are packed in their bags as amenities, accompanying them during their time at places like Abu Ghraib. [5]

22

How we “make photographs speak” is not so simply the work of looking, talking, writing, and reading out loud when additional photographs always loom. Does executive power decide to show them, does executive power show them not? Meanwhile, we bulge. The majority of the photographs from cameras in pockets lurk as open source. Even the word images send infinite possibilities on a haunt.

23

Photographers used neck braces to hold subjects still in order to secure a stable set of visual details. This was before cameras were, as we know them, designed to capture in a fraction of fraction of a second. The illusions of the occult greatly benefitted from the early years of photography.

24

When the power of cropping is frightening, speaking to the simultaneity of “the image as raw, material presence and the image as discourse encoding a history” [6] and when writing to photographs turns to obligation, silent observation, compulsion, permission, courtesy it even switches to talking to oneself. In other words I am yelling at the mirror on a slight time delay.

25

The embedded photographer invisibly writes their inability to pass beyond what Judith Butler calls the “regulation of perspective.” In her move-over-Susan Sontag Frames of War, Butler takes on the power of cropping, how the birth of a frame “can conduct certain kinds of interpretation” [7] so that a photograph with information about events is not simply dependent on language for analysis but acts reflexively on itself, whispering who gave and denied the photographer’s access. Stand right there. Take from here. Meanwhile, in the unknown work of the censored and self-censored the crop lines are even more transparent.

26

While some contemporary poetry is greatly affected by the news, the news is not yet greatly affected by this poetry.

27

Walter Benjamin calls for the writer to caption in the middle of 20th century as obligation. [8] Walter Benjamin did not own a digital camera. Writing to photography, by way of captions, seem to work even harder as consumer electronics grow in presence. Words are not bought and replaced in the same way we are producing image-making machines. Words don’t run out of batteries or lose chargers.

28

II

29

We may now envisage planetary life becoming progressively a story without words, a silent cinema, an authorless novel, comics without speech bubbles.

–Paul Virilio, The Information Bomb [9]

30

A picture-book universe reveals little about the dark side of anything — neither conceptual frameworks nor the moon.

— Joan Retallack, The Poethical Wager [10]

31

Captions for still images in the daily print mainstream news media share the following with some styles of contemporary poetry that I will discuss in this essay:

32

the value in words exercising brevity

consciousness of space within a line

parenthetical phrases as pacing breath

interruptions resulting in layering

fragments obeying content more than grammar

the authorless text / the appropriated text

33

Photographs will always have a wider distribution than poetry and therefore always have the more real potential to instigate/precipitate social change. [11]

34

The concept of a caption contains potential for reaching enlarged audiences because of its strategic placement near images.

35

When and if considered distinct from image, text can involve a more time consuming relationship. Text waits while images may distract. Photos are more subject to timelessness, news stories, being attached to a date.

36

As Benjamin calls for the radical and never consistent, the poetic captions I refer to will not always look like captions and may not even be underneath photos.

37

A great number of poets and artists are censored from or choose to not participate in courting or attaining mass audiences. This is both in reaction to and by default of their illogically small societal spaces to fit inside. [12] This does not mean that the task of poets and artists is small; conversely, it is such an overwhelming task that it often causes suffocation within these small societal spaces.

38

It is too much to ask of the news caption to perform its duty within the space the news has provided for it.

39

Ideals of poetry masquerade as truth. Photography is mistaken for truth. The word poetic is often used by art critics to describe a successful photograph or body of work.

40

People who intersect in public places like train stations possess the access to mainstream print news more so than there is a distribution of and consistent exposure to contemporary poets whose work I consider to also be the news.

41

We see poets “make (it into) the news” in the rigid and controlled forms of book reviews, announcements of readings (often where there will be a book that has been published to be signed), and designated corners of a periodicals for one specific type of poem to sit obediently. We see artists “make (it into) the news” when they have representation by the art world in forms of exhibitions and sales, do something risking offense, win one of the few prizes, or use government money with non-government moral compasses.

42

There is a call to disrupt this imbalance. In Jena Osman’s April 2007 essay on Jacket, “Is Poetry the News?” she asks, “Is there a way to have a poem do political work without preaching, monologing, speechifying, shutting down dialogue, or making use of absolutes and essentialisms?” [13]

43

And I say yes.

44

Within and beyond the shortcuts or traps of photographs to feeling personal saturation levels of being informed there is also the choreography of the spontaneous, the power of the witness, and the surfacing into discussion.

45

Often, image is text and text is image because of hypertext manifest destiny: we know there is too much to read so the word characters go into “picture book” mode. We scroll. We click away. We have inherited these methods from the spreads of newspapers. [14]

46

The image and text duo is code for an unstable interdependency between mediums and our translations to memory. We are always in the business of a chase, by making images from words and words from images.

47

Image and text are not in competition but are in collapse. Think collapsible street theater. Think lovers collapsing onto a bed after not sleeping together for a long time. The long time is not related to clocks.

48

With consumer photography enveloping citizen journalism and then increasingly comprising the news, the chase between photography and words are converging as alternatives to one another. The differences between these ever shape-shifter mediums concern materials that are available at the moment. There is here a question of convenience and funds.

49

When photography acts faster than words, or at the same time as words, there is an incessant catching up to do.

50

The lack of archiving in the refresh button makes the newspaper even more ripe for and ready to cross with literature. As Kenneth Goldsmith’s Day proves, the news is poetry on autopilot. His retyping of one New York Times from September 1, 2000 caused essays and essays of critical response. Day is essentially an image read and written to.

51

The mass circulation of the news makes it the biggest living and dying book group of readers who often don’t look each other in the eye. [15]

52

I ask what does it mean to watch people in public when they are holding a newspaper in their hands. How much of a statuesque pose is it. How much is it a school of mime.

53

How does our ability to choose more what we see in online news reading — if self-directing favorite places or sites to read from — relate to the disturbance of looking at the photographs we would never want to even exist in the first place.

54

I ask what does it mean that you won’t be able to fish for a website out of a trash bin at a train station.

55

III

56

A post conceptualist might invite more interventionist editing of appropriated source material and more direct treatment of the self in relation to the object.

— Robert Fitterman & Vanessa Place, Notes on Conceptualisms [16]

57

seeing is bereaving

— Judith Goldman, Deathstar/Rico-chet [17]

58

The perpetual state of obsolescence that print news is currently experiencing is an identity crisis that poetry can relate to. I am positioning this exciting revolution of what makes up our news media with the recent declarations of lay-offs in newsrooms, against poets in the United States who have already been making news and who aren’t doing it for the cash.

59

Some of these poets include: Taylor Brady, Judith Goldman, Mark Nowak, Kristin Prevallet, and Juliana Spahr. Not only do they generate news by writing on particular topics that have been in the daily print mainstream news or should be, but also because of their active dialogue with the problematics of news production in their work.

60

These poets role play, respectively, as: the editor translating notes from the field into captions; the spot news reporter; the alternative media investigative journalist; the editorialist; the representative for the public as reader/viewers.

61

Our news is sick. But we can’t abandon the sick. Cause effect patterns could be traced to high doses of corporate media giants pleasing advertisers. This is more about the acceptance, rejection and in between living with whatever we receive packaged as news is better than not receiving anything at all. Poets who already write of, on, about, and for the news tell it slant, so that the question of saving news with state subsidized funding and then the loss of political endorsements would be irrelevant. [18]

62

[generic human figure] claims I can get more information at home than by going to the war scene

what [generic pronoun] sees is [gendered naked bodies] in news photos — dead bodies, discarded bodies, junk

— Juliana Spahr, Response [19]

63

Going to the war-scene is not an option for many a news consumer. Not going to the war scene is not an option for thousands of recruited American youth who will die in the war scene. Only seeing a screen version of the war scene produced by drone attack software of computer buttons that get pressed to contribute to the tens of thousands of civilian casualties is not better than going to the war scene. There is no scene for those millions inside the wars.

64

As if I can even continue describing the war scene I read about in a line of poetry without stopping to consider what gets called war and then photographed to be a scene for me to think I can see some tiny aspect of something far away. This war scene meanwhile happens far from a plethora of local crisis’s whose festering daily struggles don’t get funded by hundreds of billions dollars and don’t get protected by forces.

65

And so, the cycle to “respond” never ends. It is never too early or too late. The side effect is backlog. “we try to look with eyes better than what we’ve had before”(Response, 57). The handwritten argues with the act of being typed into the mass reproducible. We are in a constant state of recuperation.

66

What we see when we look is not only the news in its fragments and illnesses, in its shades of facts, is its attempt to reveal systems of oppression. What we must also see is the reflection of us looking into that news: how the reader/viewer is parsed into the role “generic human figure” as if wading through layers of political correctness in order to pull the plunger out of that drain. Doing away with race and gender inside the poem exposes the role of institutionalized race and gender biases. Spahr asks us to insert the realities of our personal situations of separation from the context of the story.

67

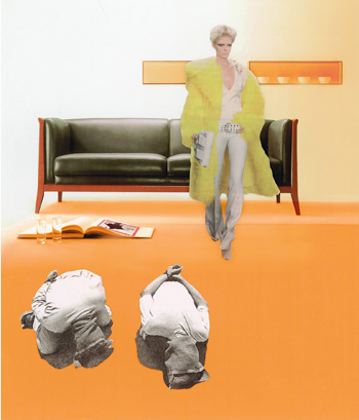

Spahr’s book Response speaks to Martha Rosler’s photomontages, spanning 1965 to the present, (pictured here, updated with a touch of Abu Ghraib) that are culled from magazine ads of middle class white women in their living rooms collaged with pieces of war scenes. Just as Rosler shoves superficial worlds together, Spahr’s bracketed cut and paste insertions pose coping mechanisms as well as a roadblock in reading. The intention is to unsmooth the digest-able visual experience. The brackets make you slow down and divert analysis, which is inherent in the embedded modes of sending and receiving news. The reader/viewer is being asked to participate in their news production.

68

Spahr speaks to how our eyes adjust to the capability of human destruction in front of us and far away, only to make looking at disturbing news images more complicated because the act explicitly points to our ability to use horror as entertainment.

69

What strikes a difference between a professional journalist and a Caption Poet is the intentionality of landing in the corrections section. An overextended newsroom employee may be in charge of the corrections hotline as well as the jpegs flowing in from the photojournalists accompanied by sparse captions. This worker is who I imagine to be the voice behind much of Taylor Brady’s poetry. The corrections may get switched up with the captions. The corrections section is often about the captions.

70

The photograph helps you feel the loss. Think never fear you order me, correspond…

He never wrote a fragment. Extracts actually grow inside the readers’ brain like cockroach eggs

— Taylor Brady, Microclimates [20]

71

Participation is partial infection.

72

The overextended Caption Poet overloads the perimeters in Brady’s work, often turning to an off stage footnote for heavy breathed asides. Microclimates enacts several miscommunications with the ominous “Editors,” as if to anonymously, begrudgingly name the framers, who are posed as the higher ups.

73

Brady makes one of his subjects the difficulty to maintain a response to the news and news production. While Brady’s writing exists as discrete books, full of disjuncture to the point of is-it-worth-it-un-readability, the organization of month and day in Yesterday’s News (Factory School, 2005) reflects a conceptual constraint at hand of matching reliable news output. The point to hint at how often the news output from mainstream sources is equally “unreadable.”

74

Fragmentary thinking is coherence to the Caption Poet: when Brady read with Susan Gevirtz under the theme of “The Fragment” at a 2008 Canessa Gallery reading in San Francisco, there seemed a mood of why us and this category. The model of a distracted worker processing language is excused from the repellent of fragment because the voice has endured and traces a disturbance of grammatical, predictable, language.

75

Brady’s rewritings and internalizations of the news works in contrast to the “Special Edition” of The New York Times from November 2009, the liberal fantasy newsprint that hit the streets care of the Yes Men collective. This commentary hinged on prank: readers were initially tricked to believe The New York Times actually printed such stories as “Iraq War Ends” and ads for conflict (and guilt) free diamonds. It was designed in all the ways the “real” paper was. Caption Poets instead exaggerate the newspapers pre-existing comprehensibility by way of uncomfortable fragments.

76

To work as a poet in this society is to function as a “participant informant”

— Judith Goldman, “Letters to Poets” [21]

77

To be a poet newsmaker may also mean to demonstrate the chaos of the news, which demands the reader/viewer’s eyes to tease words out as if trying to save a corrupted document.

78

Picture5 p0sed 0n hand5 & when he laugh5 a5…

5odomy &5h0ck5 t0 5hit 0ut th0 50me 0ne

Fucked y0u, n0r fucked luck becau5e they’re n0t queer.

— Judith Goldman, Deathstar/Rico-chet [22]

79

Captions can’t speak clearly when drugged up and dressing in the dark. The voice of captions speak a language of mashed up accounts. Was it staged? Did it hurt? Tell me where.

80

Goldman’s letters and numbers mash-up to retell news stories, as if the telling is the same as the directions of where to find the story continue. We need directions. “A5” translates doubly into the tool for comparison building, and the newsprint section names.

81

Goldman takes on celebrity gossip in her poem “Prince Harry Considers Visiting Auschwitz:” “quotEWhy can’t wE justquotE/quotEhElpquotE him pass his art Exam/” (88). The physical challenge of teasing out words, creating space between the words mentally, and reinserting space through time, hints at the physical impact of receiving the visual or textual “gory details” in the news.

82

There is so much news produced daily that demonstrating it as air tight spaces and reversals of punctuation into descriptions of punctuation is an act of realism on our spot news stories. As Guillermo Gómez-Peña relates performance to a temporary state of sanity, Goldman’s poetry argues for us to perform the news in its madness.

83

What happens when captions speak the language that reports the situation of torture if the speaker was tortured and doesn’t understand why the torture had to happen is that we lose a sense of facts and clarity?

84

You don’t need to read about the gory details to know that it was violent.

— Kristin Prevallet, [I, Afterlife] [Essay in Mourning Time] [23]

85

Prevallet sets up an opposition between reader and writer and then text and imagery. Viewers are cast as greedy onlookers, who blatantly pillage one’s suffering for their titillation. Prevallet never shies from accusation in her work and her convictions rank like editorial columnists for that reason. Her book Shadow Evidence Intelligence (Factory School, 2006) does this with almost a cookbook of “political poems” for their willingness to date themselves and use a tone of shouting only quieted by print. There is a high level of satire in Shadow’s works to imitate the matter of fact-ness of an executive order. Into a megaphone she retells the U.S. entrance into the Iraq War: “If its all about oil,/and it is”(17).

86

In her book published one year later, Prevallet announces from the introduction of I, Afterlife: “this is a story that leaves a wide margin of doubt” and then “This is elegy.” By recasting her father’s suicide within the space of poetic inquiry, she questions most persistently the act of reception of what is potentially a news story, and at the same time life altering personal event. Fore grounded is what will be inevitably cropped out when dealing with a situation that involves the intimacy of pain and multiple levels of unknowns.

87

In “[CRIME SCENE LOG 11.20.00]” of [I, Afterlife] ten square sketches of “black and grey space” function as “open closure” while the captions that run underneath these visuals are identified as “False closure: notes written at the scene of a suicide to express, normatively, the scene of the suicide”(15). With a circularity that defies elaboration is the warning of form letter language found in police files for events. Recontextualizing this language evokes images of filing cabinets exploding, and facts magnetizing out of their original context or false systems of organization.

88

To describe an abstract image is a form of protest against “gory details.” Prevallet’s commentary on the image/text coupling functions not only as an act of defiance, to evade detail in the telling of a story, but as a proposal for both the caption renovation and the spew of disturbing imagery in the news media. A sufficiently abstracted image results in the concrete text below being the focus on the page, emphasizing the practice of refusing a title to gain hierarchy on the page.

89

The monumentalizing the un-monumental caption gives a leg up to what could be talking back to imagery more actively. This is a gesture towards our living in and out the habitat of watching shocking imagery by not (only) attempting a description of the shocking but re-establishing what are the pieces of found text around it.

90

The use of Caption Poetics may or may not be found text. The primary construct is commitment to a dialogue with the news while insisting on a shape not existing in the news: persistent inquiry to what surrounds news imagery that may be excluded in news production.

91

The current modes of corrections, letters to the editor, and blog posts that are built into the news are insufficient. The underfunded alternative media, while vital, is also not the appropriate space for Caption Poetics because it follows similar forms to the mainstream media with just a shift in content and perspective.

92

We are at the rupture of what to do before, during, and after erecting public memorials. [24] Posturing what memorials are and made from, asking what is a proposition to reread the texts already written or spoken, gives the pre-existing an echo on public platforms, as we see in Mark Nowak’s work. The poetic text is the act of visitation at a monument because the process is essential to culling pre-existing language not produced under a pretense of poetry. In order for a poetic text to be (re)produced, a huge amount of research and reading through pre-existing news, and that work stands as a model posing larger than monumental stone.

93

So I told him we had 11 items, and he said, what. I said we got 11 items. And he said, forget the code. What do you mean? I said, there’s 11 deceased people. And he was just — he was speechless.

— Mark Nowak, Coal Mountain Elementary [25]

94

Reading Mark Nowak’s Coal Mountain Elementary is not an act of obedience at a memorial. Readers are guided through found American Coal Foundation suggested lesson plans lineated into poetry as if we still need buddies walking to the field trip destination of the monument. And then there are sampled voices of Sago, West Virginia Mine survivors and rescue teams, news stories of mining disasters in China, and photographs of mining locations by Nowak and Ian Teh. The voices appear on predictable rotation and function as straightforward messengers of research, of the act of listening to the people involved and close to the subject. The civic duty, the legacy the news industry has left citizen journalists, is one of constant investigative research and at the same time the work of never letting news stories disappear. The format of books pictures next to poems, is the never-ending back in forth between the mediums.

95

Mark Nowak visited the Bay Area in fall 2009 and both of his readings at Mills College and Small Press Traffic were formatted to be more “talks” than I am now going to read “Poetry” behind the podium. The goal for the poetry is dialogue, and literally, as one of his current projects are poetry workshops in Ford Motor Factories between the U.S. and South Africa.

96

Nowak’s form of caption is heavy because it is the whole book at once. It reshapes the piecemeal news of routine mining industry injustices to an overwhelming presentation of wrongs that need to be fixed. What the news doesn’t do is order itself how Nowak has arranged his book; he provides a quilting of what the news only prints in snippets and then gets replaced disparate stories. Nowak remodels the poet as not only a toiler over syntaxes in lines but as a composer of the vast quantities information hiding and in plain sight.

97

Poetic memorials are not about looking up and seeing a singular figure who initiated a war (as monuments tend to) but about ghosts of words wrapping around our skin, at ear and eye level.

98

To move entire books into the public as one whole caption, for books to be memorials is mirror work, assembling a group picture.

99

IV

100

… There are other performance events in which perception and participation are played against each other, or in which the activity of participation is an exercise of perception, further complicated by the sacrificial facsimile of the “Real Presence” of pain.

— Herbert Blau, The Audience [26]

101

At first I went looking for the news everywhere. I went to the local bar to watch the election debates. I turned on the radio to listen to it in my sleep. I emptied out recycling bins of newspapers. At one point, I settled on visiting libraries with newspapers. And then I would make handprints of news ink like a child would show their hands were messy with paint. And then I would save the water I used to rinse the newspaper from my hands.

102

I make my own museum out of the daily print media. It’s my museum because I can touch the works of art and I find the works of art for free. I do this like I refuse to pay high entrance fees at major art institutions. This is not entirely unlike receiving an automatic update from a news carrier in your pocket.

103

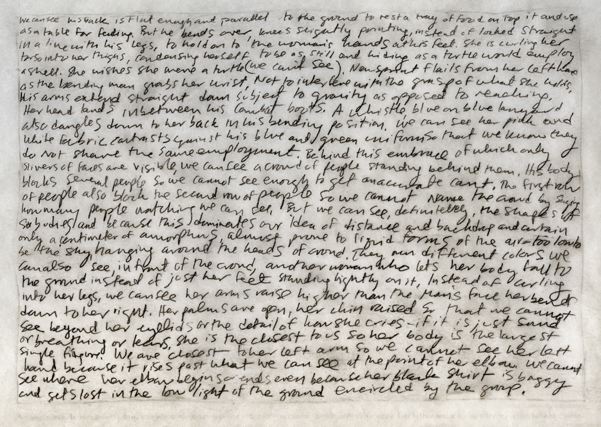

When I employ Caption Poetics I do so by conducting imaginary interviews with photographers, pressing them hard about bringing their image into the world of images. I ask the subjects of photographs to say one thing. I ask myself what do you remember from all the news consumption. I read photo manuals and photo blogs. I write about photographs as I see them technically, calling them (only) to myself, as if it’s a profanity: “objective descriptions.” Even after naming and practicing their syntaxes and repetitions, these highly formal summaries of pictures never get easier. If I find a method or a routine I tend to reverse it or act upon it with erasure. I am suspicious of leaving a trail or obeying a formula.

104

Writing captions to my news exposure at times feels like punishment because to compensate for cropping in language is an impossible task. This is the impetus for voices grappling with a crisis as opposed to the fixed documentary. There is often not a direct correspondence to one particular image. There is no linear narrative.

105

I have compiled websites of newspapers from around the world that publish news in English. I read newspapers that are not in English and only ask questions of the photos. None of this has felt natural: I am staring at obscenity but not for the immediate purpose to erase or remedy it. None of this is finished, only interrupted.

106

It seems relevant to say I haven’t lived with a television in the past few years and when I sit in front of one I feel a lot of anxiety. I can’t speak about news on TV because I don’t have much contact with it. I do listen to a lot of talk radio though. And I don’t think I am “working” when I listen like I feel I am “working” when reading the newspaper.

107

It seems relevant to say I consider all my writing to be photographs because they are such dense obsessions with the amassing of photographs in the news around me. I don’t feel like I have photographed less now that I write more than I literally take pictures. I went to school at one point to be a professional photographer. I do feel like I have been photographing less when someone asks me, do you still take pictures.

108

The transparency papers I lay directly over images to rewrite them are forms of masks that lose a face to wrap around. The photographs I literally do make tend to document the looping process of the information encounters I experience and communicate with. The analogue bent my process currently insists on is far from convenient. I have never bought a digital camera but own three hand me downs. I just found a fourth on a beach in perfect working condition but with a dead battery and no charger in sight. There is no owner responding to my Lost and Found post on Craigslist but there is someone who is looking for a different lost camera who contacted me.

109

Caption Poetics are not merely poems inspired by news imagery. [27] Caption Poetics exists for the same reasons that art stored and showed inside institutions is not enough. The book and the wall as visitation points for art is just one place and we must be in many places at once.

110

The compulsion of a written response to images in the news is not at all a new poetic practice nor does it strive to be. Gwendolyn Brooks has attributed pictures in the newspaper as inspiration for her poems. And this is to say Caption Poetics is more a means of survival with dialogue than being an emerging form. In that sense, this essay is entirely incomplete and plagued with all the silent and verbal exchanges poets and non-poets may have with the images around them supposedly containing information diagnosed as news. This is to say I read poetry to read the news and produce the news.

111

We need captions when we already have them because poetic captions follow the devastating equation of wealth and poverty that we see news circulate through daily. Poetic captions are in addition to forms following excess.

112

The photograph and its caption, each detached, on loan into our memories, seek correspondence because they get born lacking. The epistolary mode gives some hope: letters give grounding in a world of utter depravity, for a return that in reprocessing what you have seen to the gesture that something may be heard.

113

One possibility for more poetry infiltrating the news would be mass letters to the editor that don’t resemble the traditional form of letter to the editor. This idea was suggested by Leslie Scalapino when I said I don’t know what to do with the letters to every U.S. soldier announced as a casualty of The War in Iraq that I had written in 2006/7. In the singular, when I sent some of these letters to the editor, they were disqualified as not following the form of letter to the editor. They were disqualified as not relevant to the content of a specific news story within the last 7 days. Another form of intervention would be to hold readings in places where news is distributed.

114

Caption Poetics writing may ultimately be an attempt to write unsent letters to the public, how it’s the loosest form of performing for an audience, but it’s also an open letter to the systems of the media, who are shaping our ideas and spaces and types of information that enter the public.

[1] Ariella Azoullay, The Civil Contract of Photography (New York: Zone Books, 2008), 122

[2] Stanley Cavell calls our relationship to photographs and our processes of looking a failure of recognition in the exhibition and catalogue Beautiful Suffering: Photography and the Traffic in Pain that was first at the Williams College Museum of Art in 2007. The primary etymology of the verb to recognize I am considering here is the automatism of relooking: persistent hold with a photograph in the news, as opposed to the instantaneous or creeping calculation of worth over you in what you are looking at. My main question is with more photographs in our consciousness and visual streams, are systems of desensitivity more unpredictable?

[3] For more philosophy on not cropping photographs see Phil Perkis, Teaching Photography (Rochester: OB Press, 2001).

[4] Andreas Spiegl, Radical Images: 2nd Austrian Triennials of Photography catalogue, 1996, 134

http://www.neuegalerie.at/96/radikale/radikale_e.html

[5] See Susan Sontag, “Regarding the Torture of Others.” New York Times Magazine, 23 May 2004

http://www.nytimes.com/2004/05/23/magazine/23PRISONS.html?pagewanted=4&ei=5007&en=a2cb6ea6bd297c8f&ex=1400644800&partner=USERLAND

[6] Jacques Ranciere, The Future of the Image Trans. Gregory Elliot. (London: Verso 2007), 11.

[7] Judith Butler, Frames of War: When is Life Grievable?. (New York: Verso 2009)

[8]Walter Benjamin, Illuminations (ed. Hanna Arendt, Trans Harry Zohn, New York: 1978), 226. As much as Benjamin establishes the need for captions, he was addressing photography’s relationship to painting, which is now of very little relevance because photography has been established as art. We are now adjusting to anyone at any time being an influential photographer.

[9] Paul Virilio, The Information Bomb Trans. Chris Turner. (London: Verso, 2000).

[10] Joan Retallack, The Poethical Wager (Berkeley: The University of California Press, 2003), 118.

[11] Lewis Hine is just one example of a photographer who literally effected social change by working for The National Child Labor Committee Lobby, Red Cross, and Works Progress Administration. Now sponsorship by non-profits is remnant to this style of photojournalism, largely treating the Westerner as War Hero, as seen in the new graphic novel The Photographer: Into War Torn Afghanistan with Doctors Without Borders by Emmanuel Guibert telling the story of Didier Lefevre’s photographic process. The traditional photo-essay, prototypical to Life magazine has evolved to wonderful web presences such as daylightmagazine.org and PixelPress.org, obsessed with extending the caption beyond line of what the photograph can’t say in the daily print mainstream news media. There is also a wonderful blog with a completely ironic title: nocaptionneeded.com . Ever since Photo League was blacklisted by the attorney General in 1947, documentary photography has had an unwelcome relationship to the state. And while fine-art photography and photojournalism blend together more depending on where a photo is shown, the Robert Mapplethorpe show that used NEA money for any visual representations has significantly diminished. American Artists who gain respect and funding through the tiny and thus competitive circuit of institutions-who-support-social-critique even risk arrest for being suspected terrorists, as in Steven Kurtz of Critical Art Ensemble in 2004.

[12] http://www.journalofaestheticsandprotest.org/3/sholette.htm

In Gregory Sholette’s essay “Dark Matter: Activist Art and the Counter-Public Sphere,” he writes of the unseen yet necessary churning machine of the art-world. In relation to caption poetics, I align myself with Sholette, electing not a few poets for the task but the employing what he calls the “collective and informal work largely relegated to the shadows of art history but also non-professional, cultural practices”(3).

[13] Jena Osman, “Is Poetry the News?: The Poethics of Found Text” Jacket 32, April 2007. http://jacketmagazine.com/32/p-osman.shtml

[14] In lengthy pieces, usually housed online, authors may have no expectation a reader will engage with their whole text. Robert Fitterman names this a shift from readerships to thinkerships. Tan Lin names his poetics ambient in a manifesto style introduction to his book BlipSoak01. Erika Staiti’s project http://www.saidwhatwesaid.com/ meanwhile reads as a sort of photo album of the Internet niche of poets’ blogging or rather arguing around topics like race and gender on blogs. The articles or text within the news is furthermore or increasingly an image because of the current legal debates about rights to news stories when aggregate sites reproduce or link to them. The AP is fighting for rights, i.e. price tags to be set up in the same form of royalties for photographs with photojournalist agencies. Before the half tone was invented at the turn of the 20th century everything was different. See John Tagg for more on the invention of halftone’s influence on photography.

[15] The New York Times claims 25 million readers daily.

[16] Robert Fitterman, Vanessa Place. Notes on Conceptualisms (Brooklyn: Ugly Duckling Press, 2009), 22.

[17] Judith Goldman, Death Star/Rico-Chet. (Oakland: O Books, 2006) 102.

[18] John Nichols and Robert McChesney’s “The Death and Life of Great American Newspaper” in The Nation from April 6, 2009, proposes government subsidies for the engines of the news, not necessarily the print media.

[19]Juliana Spahr, Response, 1996, 17. http://www.ubu.com/ubu/spahr_response.html.

[20] Taylor Brady, Microclimates (San Francisco: Krupskaya, 2001), 17, 135.

[21] “Letters to Poets: Leslie Scalapino and Judith Goldman” Jacket 31. Oct.

2006. http://www.jacketmagazine.com/31/lett-scal-gold.html

[22]———. Death Star/Rico-Chet. (Oakland: O Books, 2006) 79.

[23] Kristin Prevallet [I, AFTERLIFE] [ESSAY IN MOURNING TIME] (Ohio: Essay Press, 2007) 11.

[24] Jules BoyKoff and Kaia Sand, Landscapes of Dissent: Guerilla Poetry & Public Space (Long Beach: Palm Press, 2008) has prompted a number of my thoughts in this essay, as I continue to ask how we can push more case studies into that category that are not only taking poetic and artistic practices into consideration, as the idea to put more poetry into the news is asking to reduce the use of genre labels for the purpose of restricting exposure.

[25] Coal Mountain Elementary (Minneapolis: Coffee House Press, 2009)

[26] Herbert Blau. The Audience (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1990) 166.

[27] Henry Lyman interviews Gwendolyn Brooks: http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=9560637

Ariel Goldberg

Ariel Goldberg is a text, performance, and photography based artist who builds conceptual inquiries about information consumption and production. Recent projects can be found at arielgoldberg.com. She lives and works in the Bay Area, California.