| Jacket 40 — Late 2010 | Jacket 40 Contents | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 17 printed pages long.

It is copyright © Harryette Mullen and Barbara Henning and Jacket magazine 2010. See our [»»] Copyright notice.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/40/iv-mullen-ivb-henning.shtml

JACKET

INTERVIEW

Harryette Mullen, photo by Hank Lazer

Harryette Mullen: From S to Z

Harryette Mullen in conversation with Barbara Henning

Long Island University, mid-2009

Harryette Mullen is an American poet and short story writer and academic scholar. She was born in July 1953 in Florence, Alabama. She grew up in Fort Worth, Texas, graduated from University of Texas at Austin, and attended graduate school at University of California, Santa Cruz. She is the author of Tree Tall Woman, Trimmings, S*PeRM**K*T, Muse & Drudge, Blues Baby, Sleeping with the Dictionary (discussed here), and Recyclopedia. She teaches American poetry, African-American literature, and creative writing at UCLA. Wikipedia says “Especially in her later books, Trimmings, S*PeRM**K*T, Muse and Drudge, and Sleeping with the Dictionary, Mullen frequently combines cultural critique with humor and wordplay as her poetry grapples with topics such as globalization, mass culture, consumerism, and the politics of identity.” Currently (2010) she lives in Los Angeles.

1

With Harryette Mullen’s dense, layered and playful poems in Sleeping with the Dictionary, there is often a subtle question, almost present but not quite present, a riddle-like structure that leaves the reader wondering: How did she make this poem? As a prep for an MFA course I was teaching at Long Island University in the summer of 2009, and as a project I knew I would enjoy working on later, I decided to ask Harryette if she would be willing to talk to me about each of the poems in this collection, and then I would share sections of the interview with the class. This interview would be in the spirit of the Oulipo artists who reveal their experiments and constraints and catalogue them in their library in Paris. No secret mysterious inspired “writer-self,” but instead a writer who is seriously inventive and willing to share her methods and approaches. It was very curious and enlightening to the students to discuss and then hear some of the writer’s intentions, context, and the way she had constructed the poems. We of course weren’t searching for “meaning,” but instead aiming to help writers expand their own repertoire of tools for writing and to think about the reasons writers write the way they do.

2

For the most part, this interview follows Harryette’s alphabetical structure for Sleeping with the Dictionary. Other excerpts of the interview are available in current or upcoming issues of The Poetry Project Newsletter, How2blog, Sonora Review, Eoagh, and Naropa’s online magazine, Not Enough Night.

3

BH: After Ithaca you’re in LA and you find yourself “Sleeping with the Dictionary.”

4

HM: Well, we already talked about the way I wrote this, my experience of falling asleep and waking up in bed with my American Heritage Dictionary. It gave me a personal connection to the Oulipo technique of S+7. Also it was important because, once I focused on the dictionary as a writer’s companion, collaborator, and partner, I had a more coherent framework for the book as a whole. I understood more clearly that all along I had been writing about the potential of language for power and play, and I could imagine the dictionary as a speaker or character in the work.

5

BH: Actually I was thinking as I read this poem and I don’t know if other reviewers or critics have talked about this, but even though there is this playfulness that keeps things going, there is this undercurrent of loneliness, even with the title Sleeping with the Dictionary. But then language itself offers a remedy, the playfulness and joy of a riddle, a pun, a parody. That tension between the two, I think, keeps the whole book moving.

6

HM: I don’t think anyone else has talked about this book in quite that way. It’s true that I was learning again how to live alone, but I was also jumping into a new life, starting over in a new place. I’d lived in California before as a graduate student, but this time I was moving to Los Angeles, which is so different from the northern part of the state, and I was becoming a permanent California resident. My brain was stimulated by the different rhythms of life, as I tried to tune in to the culture and politics of the place.

7

This was a time when debates were raging. There was a great deal of controversy over issues such as affirmative action, bilingual education, and immigration, as California was becoming a “minority majority” state, where there is no longer a demographically dominant ethnic group. All of that got me to thinking how cultural and political divisions are expressed in language. Although the dictionary is considered an authoritative reference for accepted usage, in reality we are divided in the ways we use language. Dictionaries are attempts to identify or create standard usage and definitions, but of course the dictionaries don’t exactly agree among themselves. In disagreement there is tension, confusion, resistance, and conflict. But also in our disagreement, and in the way language disagrees with itself, there’s room for critical thinking, humor, and play.

8

I love dictionaries myself. I have a small collection of dictionaries and thesauruses. I also collect dream books that serve as dictionaries of metaphors. But I’m aware that many people don’t share my appreciation. I think my title expresses opposing views of dictionaries. One group of readers thinks of falling asleep because the dictionary is so dull, while another group thinks of the dictionary as a seductive companion. My book appeals most to those who can imagine having fun with a dictionary.

9

BH: It sounds like the people who enjoy examining the little turns with words and phrases, disjunction between beginnings and ends, realize that through transforming language you can change reality — they may be the same people who enjoy reading your poems. Those who want their poems to be clear and straightforward, believing that’s what poetry should do — well this won’t be their thing. . . . T.S. Eliot explains why people should not like Stein: “Her work . . . is not amusing, it is not interesting, it is not good for one’s mind. But its rhythms have a peculiar hypnotic power not met with before. It has a kinship with the saxophone. If this is of the future, then the future is, as it very likely is, of the barbarians. But this is the future in which we ought not to be interested.” Maybe our readers still divide like this.

10

HM: Eliot sounds like the people who warned that jazz was “jungle music.” That listening to jazz would lead to the decline of civilization. It did lead to the decline of the idea that only Europeans were cultured, civilized human beings. But Eliot and Stein were probably not so far apart in how they viewed people of African descent.

11

BH: Let’s start the last lap of this interview by discussing “Souvenir from Anywhere.” It sounds like we are in a new age boutique here.

12

HM: That’s a good description. When I travel, I like to look for handmade crafts. Sometimes the artisans sell their goods at outdoor bazaars. But often these items are marked up and sold in expensive boutiques that cater to tourists. I also thought about the merchandising of progressive ideas, as well as ethnic and identity politics, with catchy slogans printed on posters, bumper stickers, buttons, and t-shirts. Sometimes there seems to be a conflict of values in what these goods might represent to the buyer and the seller. At the Oakland airport I noticed a vendor with t-shirts that read, “We’re all just a box of crayons.” Does that mean that every color is equal? In several shops in San Antonio’s Old Town that specialize in Mexican and Native American crafts, I saw signs that read, “Unattended children will be sold as slaves.”

13

BH: That’s not funny at all.

14

HM: It didn’t strike me as funny either. But I have seen it in boutiques and gift shops where they sell a lot of knickknacks, and they don’t want children running around, breaking things. I couldn’t help thinking that there’s a real market that traffics in children, just as there’s a market for handicrafts made in developing nations, including some items made by child labor. This is another poem that pieces together scraps of familiar slogans, threadbare clichés, and borrowed language, from political manifestos and captions on t-shirts to the signs that merchants hang on the wall behind the cash register. I often make poems from recycled materials, like Duchamp’s “readymade” art works.

15

BH: Suzuki Method — “ElNiño brought a typhoon of tom-toms from Tokyo, where a thrilling instrument makes an OK toy. Tiny violins are shrill. . . . We both shudder as the dictionary thuds.”

16

HM: The inspiration for this poem was a trip to the Watts Towers with a visitor from Japan. Like most neighborhoods, Watts has changed over the years. Now it’s mostly Latino or Mexican American, as it was before the great migration of Anglo-Americans. By the 1940s Watts had many white residents, and by the 1960s it was mostly black. The Watts Towers are the creation of an Italian immigrant, Simon Rodia, who built the structure using materials he found and recycled, including ceramic tiles, glass bottles, and seashells. But he didn’t name them the Watts Towers. To him they were the ships of Marco Polo. Those towers are the masts of the ships. If you go to the Watts Towers there is a sign that explains all that.

17

BH: I didn’t remember that. You took me to the Watts Towers when I stayed at your house.

18

HM: I like to take visitors to the towers, if they’ve never seen them. So I was showing around a visitor from Japan whose dream was to make Hollywood movies. His plan was to support himself as an extra while writing screenplays, and work his way up to directing films. He was having problems getting anyone to read his scripts because it was obvious that he wasn’t a native English speaker. Of course, his English was much better than my Japanese, which is less than zero. So the theme was East meets West.

19

BH: And how did you make this poem?

20

HM: The poem includes some anagrams. There are connecting ideas, like music and Esperanto as universal languages. Also the Suzuki method of teaching music to young children is called the “mother tongue approach” because it assumes that children can learn music in the same way they learn their native language. Of course, I was thinking about miscommunication across a language barrier. But at the same time, I thought about the common impulse to explore new worlds, or worlds that are new to us.

21

BH: In “Swift Tommy,” it seems like you are mocking people who claim to know things.

22

HM: Yes, overall I think this poem comments on the role of knowledge workers or gatekeepers of information. This started when a friend told me that she misses punctuation, which she notices that writers are using less and less. Another friend told me that in a presentation to international scholars she had to explain the difference between a pink-collar worker and a redneck. I think the best lines in this poem are actual quotations that I’d heard or read. I pieced together found quotations and invented quotations. I guess I was mocking the authoritative tone that we assume as academics trained in our particular disciplines. After so many years working in academia, I sometimes wake up in the middle of the night and realize that I’ve been lecturing in my sleep. People tell me that when I’m talking in my sleep I sound very authoritative.

23

BH: That’s funny. I sometimes dream I’m at a poetry reading, but I’ve forgotten to bring any poems (laughter). And many of the lines in this poem are hilarious. It’s like a list of jokes piling up on top of each other. “The old crock tearfully confided to the young salt, ‘A wave of mock cashmere turtlenecks swallowed my ethnic pride, and I can’t believe it’s not bitter.’”

24

HM: The title and the poem are inspired by Tom Swifties. That’s a kind of wordplay named for Tom Swift, a fictional hero whose name is associated with this sort of pun that’s usually in the form of a quotation. For example: “I’m on my way to the cemetery,” Tom said gravely; or “There’s room for one more,” Tom admitted.

25

BH: And then a list of short lines, “Ted Joans at the Café Bizarre.” I was reading about Ted Joans and how he had invented outography where you cut the image out of the poetry. I thought maybe you were cutting words out of his work.

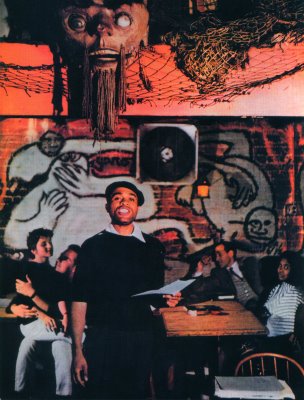

Ted Joans, reading poetry in the Café Bizarre.

26

HM: I don’t know for sure that those words are in his work. Those images recall my thoughts about his work and his life. Like Bob Kaufman and Jayne Cortez, he saw a connection between jazz and Surrealism, claiming both as artistic and political weapons. I read that he was born near Cairo, Illinois on a riverboat where his parents were entertainers, and his life was a perpetual journey with no stable place called home. He traveled all over the world, visiting ancient destinations in Africa like Timbuktu and the original Cairo in Egypt. He was supposed to have fathered a dozen or more children with different women. So I thought of him as someone creating his own personal diaspora of offspring, poetry, and legend. I got the title from a photograph of Joans reading poetry at Café Bizarre, one of the Beat hangouts.

27

BH: Did these words come to you as an improv as you were looking at the photo?

28

HM: It wasn’t the photograph, but the caption that got me started. It was the idea of Ted Joans at Café Bizarre. As you pointed out, my book begins with a quotation from Breton. So this poem, along with “Fancy Cortex” and “Zen Acorn,” acknowledges African Americans in the tradition of African and Caribbean Negritude poets who allied themselves with anti-colonialist French Surrealists.

29

BH: “Transients” seems like another story that is unfolding through bits and pieces of experience collaged together, like “Quality of Life.”

30

HM: That’s right. When I was a student I read a novel by Alison Mills that Ishmael Reed published, called Francisco. One of the characters never seemed to have any permanent home, and when the narrator leaves her home, she says, “I lived like Boopsy, from place to place.” So this poem, “Transients,” was about a time when I was living like Boopsy. I was recalling places where I have lived when I was almost but not quite homeless. At a certain point I was living a sort of down-and-out bohemian or graduate student life, and sometimes living in difficult situations.

31

I also went back to childhood memories of neighborhoods I grew up in, people who lived in unconventional housing, and people who seemed to live comfortably without a lot of money. One of my poet friends told me that she lived for a while as a squatter in an abandoned building in Manhattan. I connected those memories to my own situation, except that my poverty, thank goodness, was temporary. The poem begins with, “Vines through the roof of the tool shed.” It’s a memory of a place I came close to renting when I was a graduate student. I was sleeping on a foam pad in a garage with a concrete floor. I was trying to find another place, and one of the places offered for rent was literally a tool shed with vines growing through holes in the roof and walls, another was a gazebo. The previous tenant had camped out in the gazebo with a sleeping bag.

32

BH: Sounds like India. When I first read the poem, I thought it was about traveling and I guess it is. You are traveling through the places you lived and other people have lived.

33

HM: People were charging rent for these uninhabitable structures.

34

BH: Where was this?

35

HM: Santa Cruz. It’s a university town and also a beach town where normal rentals were incredibly expensive. There was so much demand for housing below the market rate that people were renting out their tool sheds, garages, laundry rooms, and kitchen pantries. People with houses rented space to students, surfers, and transient hippies who needed temporary housing.

36

BH: Many of the poems, like this one, are much more personal than Trimmings, Sperm Kit and Muse and Drudge.

37

HM: Well, yes, because most of these poems were written after I’d moved to Los Angeles. So I was responding to a new environment, trying to understand where I was and how I fit in. By now I’ve lived here longer than anywhere since I left my family home in Texas. Somehow it worked out that I left California before the Loma Prieta earthquake hit Santa Cruz, and I returned to the state after the Northridge quake in Los Angeles.

¶

38

BH: Sorry, the tape skipped there. We already talked about “Variation on a Theme Park” when we talked about “Dim Lady,” so let’s skip ahead. “Way Opposite” is one of the poems that functions as a lyrical riddle in between the more dense prose poems. “At the sign of a red palm / I don’t walk, / I run.”

39

HM: “Way Opposite” was inspired by a children’s book by Richard Wilbur called Runaway Opposites. The most interesting poems juxtapose unexpected opposites, like weeping willow and laughing hyena. I began my poem with the “Don’t walk” traffic signal for pedestrians, a red palm that looks like the signs posted by fortune tellers. So I could imagine that the antonym of “walk” is “a psychic with a crystal ball.”

40

BH: Lorenzo writes that in “We Are Not Responsible,” you exploit the language employed by bureaucracies, corporations to issue disclaimers and liability limiting self-serving lies and safety instructions. I thought it did that, but even more. Did you take this language from somewhere else?

41

HM: In a general way it’s about the social contract. The borrowed language in the poem runs the gamut from airline safety instructions and corporate disclaimers to the Supreme Court’s ruling against Dred Scott. This was written before 9–11, when profiling was widely accepted as necessary for security. But even before that terrorist attack, racial profiling targeted people of color as potential criminals, as in the police shooting of Amadou Diallo. We who consider ourselves to be law-abiding citizens have surrendered a lot of our freedom in order to feel safe.

42

The poem plays back the language of authority in what seemed to me a logical movement from the rules and regulations we must obey as airline travelers to the whole system of laws derived from original documents proclaiming rights of white male property owners. What might be unnerving when I read this poem to an audience is that I keep repeating the word “we.” Instead of “us and them” it’s “we and you,” so it’s a bit skewed when I speak in the voice of the authoritative “we” versus “you” whose rights are threatened or violated.

43

BH: In Bettridge’s review of Sleeping he says that “Why You and I” is “a critique of singular pronouns as representative tools.”

44

HM: When I arranged the poems in alphabetical order, I saw that the letters I, U, and Y were missing, so that’s when I wrote the poem, “Why You and I.”

45

BH: I like the way it plays around with the pronouns. “Who knows why you and I fell off the roster?” Were you thinking of your own relationship?

46

HM: Well, you and I both know how interesting and difficult it can be to live under the same roof with another writer or another creative person. But it could be any relationship, or it could be even a relationship with language and writing. Maybe it’s the relationship of the reader to the poet or the poem.

47

BH: Besides using the title as an entry, did you use any particular method or constraint to write it?

48

HM: Only the repetition throughout of “why you and I” in each sentence, with words like roster, muster, books, list, and alphabet referring to this work as a whole. It can be understood as the failure of a union or relationship. Literally it’s about the absence of three letters that failed to show up for roll call, thus disrupting the alphabetical order of the book. It’s also another poem that borrows from the tradition of riddles.

49

BH: “Wino Rhino” is clearly about the homeless. “For no specific reason I have become one of the city’s unicorns. No rare species, but one in range of danger”

50

HM: Yes, I was thinking about homeless people and the extremes of poverty and affluence in a city like Los Angeles. I can recall when many people were driving SUV’s, Jeeps, and Hummers, as if they were fighting a war or going on safari instead of navigating through city traffic. I had the image of a wilderness reserve that tourists drive through in a Jeep to observe the wildlife, only here they’re driving through the urban habitat of homeless street dwellers, the rhino winos.

49

BH: And the homeless are the city’s unicorns.

51

HM: The city’s homeless are the urban legend that everyone knows about without any firsthand experience. The rhino never gets close enough to turn over their jeeps. Some of the homeless guys, instead of begging, offer to wash your windshield when you park on the street or even when you’re just waiting at a stop light. A lot of people will give them a few bucks, but will say, “No, don’t wash my windshield.” They don’t want these guys to touch their vehicles with the grimy rags they’re using for the job, because it would just make the windshield that much dirtier and streakier. Sometimes all the man on the street has to do is offer and the driver says, “Okay, I’ll give you a handout, but just leave my car alone.”

52

BH: Sometimes the people who beg and wash windshields can be intimidating. Sometimes they are mentally impaired. This is in New York City anyhow… Some are definitely in need of help. Most of the people on the streets — I don’t know if this true anymore — arrived when in the 80’s they emptied out all the mental health facilities and just dumped the people on the street.

53

HM: Deinstitutionalization started as a movement to protect the rights of the mentally ill.

54

BH: Suddenly you had all these people who needed care just wandering around without any help. Maybe they were better off though. Maybe there was more freedom on the street.

55

HM: Some of those mental asylums were terrible institutions, but they needed more community halfway houses so they could live in a smaller, homier environment. They need access to medicine and healthcare.

56

BH: Yes, in your poem you point out of the disparity between those who have and those who don’t. “My heart quivers as arrows on street maps target me for urban removal. You can see that my hair’s stiffened and my skin’s thick, but the bravest camera can’t document what my armor hides. How I know you so well.” And the homeless are the unknown outsiders. But they know us.

57

HM: People who live on the streets have time to observe us as we rush by, trying not to see them. I wrote the poem from the perspective of a homeless person, although this speaker is not any particular individual. The image of a person turning into a rhinoceros goes back to Ionesco’s absurd drama, but this kind of metamorphosis is common in literature.

58

BH: In “Wipe That Simile Off Your Aphasia” you are substituting odd words, like prepositions for nouns: “as horses as for” “as cherries as feared” “as umbrella as catch can” “as penmanship as it gets.” Was this random or was there a method here?

59

HM: I’ve seen an article about this poem that discusses the use of “cognitive similes.” At the time I wrote the poem, I don’t think I had any particular method — just an observation about habitual phrases that aren’t similes although they use the word “as.” My idea was to treat these phrases as if they were poetic similes. At the end, after the extended anaphora, I tried for a sense of closure. I think the rest of it was sort of random. I should say intuitive instead of random. What I’m doing isn’t truly random in the way some writers and artists use aleatorical procedures to counter the individual’s intention or subjectivity.

60

The next poem is “Xenophobic Nightmare in a Foreign Language.” That title is borrowed from an artwork by Enrique Chagoya. There’s another different Chagoya drawing on the cover of this book.

61

BH: I love that image on the cover, the shifting face and the hands springing out her body, but especially all those eyes.

62

HM: Yes, with reference to Picasso and Disney, this drawing suggests that there’s more than one way of seeing. It’s why I like going to museums and galleries. There’s the pleasure of the art itself, and then I get so many ideas from artists. Chagoya is a Mexican-born artist who teaches at Stanford. I met him when he had a show here in LA. I copied several of his titles into my notebook, and later I got his permission to use his drawing for the cover. This could be called a “found poem” or “altered text.”

63

I mean, it’s the actual text of the Chinese Exclusion Act, a law that prevented Chinese from immigrating into the United States in 1882. I did cut or condense the text that Congress wrote, which was longer than this. Other than that, the only change I’ve made is the recurrent substitution. In each instance where the law referred to “Chinese” or “Chinese worker” or “Chinese immigrant” I substituted “bitter labor.”

64

BH: That really makes it odd.

HM: I don’t know if this is strictly true, but the word coolie — you know they used “coolie” to describe the Chinese immigrant workers — I read that “ku li” in Chinese means “bitter labor.” But this word “coolie” was used as a racial slur against Asians.

65

BH: “Bitter labor.” Is that like resentful labor? How is “bitter” used here?

66

HM: Bitter labor or bondage labor. I thought it referred to contract labor or indentured labor that is similar to slavery, or any extreme kind of “alienated labor.” Like other immigrants, they did some of the hardest work. At one time, the government allowed Chinese men to come here to work without women or families. Immigrant Chinese helped to build the transcontinental railroad, for example, and sometimes they got blown up in explosions. If there was hazardous work — like when they dynamited mountains to make railroad passes — the Chinese men, who came here without families, might be used for this dangerous work.

67

BH: Still “bitter” is like attitude here or a flavor.

68

HM: That’s right. U.S. immigration policy sometimes behaves like a child trying some new “exotic” food, and then spitting it back out. It’s like that old advertising slogan, “We don’t want tuna with good taste. We want tuna that tastes good.” The nation needs to guard its borders, but it also needs cheap labor. For the immigrants, “bitter labor,” could mean their attitude toward the work but it also could be the work itself was bitter. I think it could go either way — labor might be bitter about how they are treated and also the work they do might be bitter.

69

Historically slaves and descendants of slaves, immigrants, convicts, and unskilled laborers have been restricted from all but the least desirable work. Racism against the Chinese was very strong in California during the 1800s, when the gold rush attracted immigrants from all over the world. Mark Twain wrote that in San Francisco a Chinese man was stoned to death in broad daylight.

70

BH: You took the whole document, clipped it and changed a word like that. It’s a conceptual project that is political and revealing. We forget all these old documents unless someone puts them in front of us again.

71

HM: Everything else is verbatim. I included the date to give it some context because if you google that date, you would probably get the entire text of that document. The title and the date serve as a frame for this altered historical document.

72

BH: Yeah you’re right. I just googled it and it came right up. The so-called democracy after slavery had already been abolished and here was Congress making acts to exclude a particular ethnic group. They didn’t even try to hide it. . . . And then we’re at “X-ray Vision.”

73

HM: For me, this is a simple little poem about a relationship at a moment when one person’s trying to get the other person’s trust. It could also be me as the author of this book saying, you can trust that I’m making some kind of sense. I’m sure you’ve had the experience of readers or students telling you that your work or some other writer’s work is too difficult, opaque, obscure, or whatever. That a poem isn’t simple, clear, transparent, or whatever they think it should be. It’s often the first response that students have to poetry that’s unfamiliar to them, a defensive reaction when they’re afraid they’re not getting it. So I think this speaks on both levels, asking the reader to trust me as human being who is not trying to trick you, and as a poet who might break the normal rules of discourse to find other ways of making sense.

74

BH: Four different ways of saying the same thing, but of course they are all different, but they are four attempts at the same thing. “You don’t need X-ray vision to see through me / No super power’s required to penetrate my defense.” So it isn’t as hard as you think it is. Just go with it. “Without listening to your mother’s rant / you can tell that my motives are transparent.” You can figure it out without trying so hard. “A sturdy intuition could give you/the strong impression that my logic is flimsy.”

75

HM: Poetry doesn’t have to be rational. Our understanding is often intuitive.

76

BH: “Before the flat lady sang the first note of the book, / you knew that my story was thin.” Before you even opened this book you knew it wasn’t going to be easy going clear and concise. Also you knew before you got into this relationship that I talk around and about things.

77

HM: You knew to expect a difference between story and song.

78

BH: Like “Zen Acorn” for Bob Kaufman.

HM: You can see how very simple it is. I was thinking of Bob Kaufman and his legendary “Buddhist vow of silence.” I thought of the Zen koan, “What is the sound of one hand clapping?” which is similar to that chestnut of Western philosophy, “If a tree falls in the forest and no one is there to hear it, does it make a sound?” That was the inspiration for this little riff about “a frozen / indian acorn,” which is the seed for the entire poem. All of the words in the poem came from that first image, “a frozen / indian acorn.” The whole poem grew from that.

79

BH: And then “Zen” was already in frozen.

80

HM: Afro Zen was there in “A frozen,” suggesting this A-Z tribute to Kaufman.

81

BH: You often write with riddles, and there is a koan-like nature to the poems, almost but not quite unsolvable and unexplainable.

82

HM: I definitely was thinking about the enigmatic language and simplicity of the Zen koan, and also the inscrutability of some of Kaufman’s lines. I think the difference between the riddle and the koan is that a riddle is designed to be solved, like a code can be cracked; but a koan is meant to be a focus for endless contemplation, like the ultimate mystique of Kaufman’s life and work.

83

BH: Now we are at the end with “Zombie Hat.”

HM: When I wrote it, it seemed that everyone I knew was on medication and I thought why am I not taking anything? Maybe I need to be on medication, too.

84

BH: Maybe you already are on medication. That’s why you write like this.

85

HM: (Laughter) Remember when there was a big controversy about Prozac? We heard that Prozac makes some people more depressed and more suicidal. Or that Prozac replaces your real character with a personality that’s more socially acceptable.

86

BH: But maybe duller.

87

HM: Prozac makes you more prosaic? But if some people really do need antidepressants, they should take them. At times when I’m feeling a bit downhearted, I wonder, “Am I depressed enough that I need something or should I just get more exercise?”

88

BH: You’re not clinically depressed.

89

HM: No, but if I were depressed to that extent, I hope I would go to the shrink and get some medication. People who feel severely depressed or suicidal should definitely get help.

90

BH: I agree but when Prozac was first popular there was this little article in the back section of the times about a study they had done on dogs that were confined to small places all day long were much more content if they were given Prozac and that’s how I think about it. It’s often a way of not changing the situation that needs changing but instead just adjusting the chemistry.

91

HM: It’s not only Prozac. I’m amazed that people get injections of botulism toxin as a cosmetic treatment. There are so many drugs and procedures advertised, and frequently the potential side effects are worse than the symptoms they treat. If you’re trying to grow thicker lashes, you could end up with an eye infection. The prescription for toenail fungus could destroy your liver. It seems we are continually urged to pursue some elusive ideal of how we should look and feel. We have to resist becoming zombies. I don’t want to be a consumer zombie any more than I want to be a patriot zombie. We have to think for ourselves.

92

BH: I think that might be an important message of your book with all the riddles and poems that require the reader to think and decode and see things differently — “We have to think for ourselves.” And maybe we have to hammer some cracks into the structure and twist things around so we see what’s going on and also so we can laugh at ourselves.

93

HM: We can use whatever critical tools are at hand, even those once claimed as the master’s exclusive property. We can laugh at ourselves and at those old masters too.

94

BH: Well here we are at the end of the book and the end of this interview. I guess my last question for you is about what you are doing now. Is the dictionary closed? Or are you still working with it?

95

HM: My latest creative endeavor is a practice that connects poetry writing with a habit of walking and hiking in Los Angeles. And for the last few years I’ve been working on a family history project. I’ve collected several files of information that I’m hoping to turn into readable literature. In the meantime, I’ve published articles in genealogical journals and I’ve made a dozen or more collages with old photographs, letters, and other documents, including World War II ration books that my grandmother saved, and an itemized bill from the doctor who delivered my mother. When I see the handwriting of my great-grandparents, it’s astonishing to think that they were the first generation of my African-American ancestors to attend school and acquire literacy. Their parents had been slaves, legally forbidden to learn to read and write.

96

BH: Your great-great-grandparents were forbidden to read and write and you fall asleep studying the dictionary. How does this project relate to your work in Sleeping with the Dictionary?

97

HM: The dictionary remains my constant companion; but at present I’m using dictionaries in a more conventional way, sometimes looking up diseases and disorders recorded on the death certificates of my ancestral relatives who were former slaves and children of slaves: not only rheumatism and hemiplegia, but also consumption, pellagra, and marasmus — terrible words. But knowing how they died gives me a sense of how they lived and makes me want to learn more about them. Anyway, I want to thank you, Barbara, for initiating this project, and for your thought-provoking questions. I’m glad we were able to do this together.

98

BH: Thank you, Harryette.

Barbara Henning, at Veselka, 144 2nd Ave, New York, 2010

photo by Micah Saperstein

Barbara Henning is the author of three novels, seven books of poetry and a series of photo-poem pamphlets. Her most recent book is a novel, Thirty Miles from Rosebud (BlazeVox, 2009). A collection of poetry, prose and photos, Cities & Memory, is forthcoming from Chax Press. She teaches at Long Island University in Brooklyn, as well as for the Poetics Program at Naropa University.