| Jacket 40 — Late 2010 | Jacket 40 Contents | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 8 printed pages long.

It is copyright © Emma Bolden and Jacket magazine 2010. See our [»»] Copyright notice.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/40/r-edmond-rb-bolden.shtml

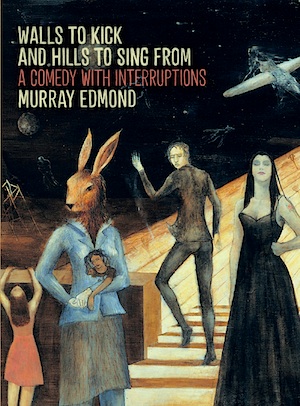

Murray Edmond

Walls to Kick and Hills to Sing From: A comedy with Interruptions

Auckland University Press, 2010, 72 pp. Paper. U.S. 14.95 ISBN 978–1-86940–458-1

reviewed by

Emma Bolden

image to come

1

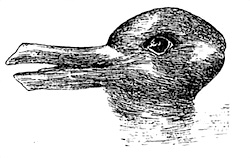

Is it a rabbit, or is it a duck, or is it both? Since its publication in 1953, readers of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations have faced this surprisingly difficult question in the text’s discussion of the Gestalt Shift. Wittgenstein illustrates, defines, and explains this phenomenon by providing this readers with a drawing which, when looked at one way, appears to be a duck; when looked at another way, the drawing appears to be a rabbit. Therefore, the viewer’s perception of the drawing changes without any change in the drawing itself, and the drawing becomes two things at once.

2

In Walls to Kick and Hills to Sing from: A Comedy with Interruptions, Murray Edmond achieves this same kind of shift, forcing the reader to perceive the poems through two very different lenses at once. The collection is a masterful execution of form which breathes new life into formal poetry and, at the same time, such a complete subversion of form that it proves such structures obsolete.

3

This Gestalt Shift exists in the very structure of the book itself almost as clearly as in Wittgenstein’s duck-rabbit. Edmond names the six sections of the collection after six points of Freytag’s pyramid, perhaps the most traditional and conventional narrative structure. While this suggests a linear book-length narrative, the poems in actuality buck the increasingly dominant present-day trend of the book-length narrative sequence, in which individual poems act as pieces of a larger project and cannot complete their act as individual pieces, unable to stand independently. Instead, the poems fight against narrative and linearity, developing a series of themes and thoughts rather than a narrative.

4

The Gestalt Shift is therefore cleverly incorporated in the structure of the book itself, as it occurs within the framework of what is traditionally the most conventional narrative structure, suggested, discussed, and followed from the theatrical competitions at the Festival of Dionysus to contemporary dramaturgy. In fact, Edmond deliberately calls to mind this history in “The goat in Auckland”: the speaker arrives at a theatre to find a goat tied to the door. A tragedy occurred within, though “[t]he goat had no idea,” and therefore “[o]nly the goat / remained waiting for whoever.”

5

In this poem, Edmond calls to mind the basis of the very word “tragedy” in the Greek tragodia, meaning “goat song;” the reader, therefore, expects the goat’s presence to be synonymous with tragedy. Instead, the goat is completely divorced from the tragedy which occurs within the theatre, knowing nothing about it and instead waiting in hopeful stupidity.

6

As Wittgenstein’s duck-rabbit contains multiple meanings, so does Edmond’s goat, a figure that stands chained to tragedy as the source of the term’s original meeting, but also as a figure completely separated from its original meaning, waiting for another meaning, another purpose. And just as Wittgenstein uses his duck-rabbit drawing to exemplify and explain the idea of the Gestalt Shift, so does Edmond’s goat represent the difficulty with form and structure, especially in terms of language systems: language remains chained to meaning, but, at the same time, is essentially devoid of meaning, much as Charles Sanders Peirce theorized that words work as signs, chained to but nonetheless completely separated from meaning.

7

By drawing the audience’s attention to this enigma, Edmond leads the reader to question the capabilities and assumed sureties of form and language in a manner which parallels and extends the Modernists’ questioning of the efficacy of language.

8

In particular, Edmond’s work follows — though it soon departs from — Gertrude Stein’s theories about language and poetry. Like Stein, Edmond’s poetry suggests that language is incompetent in — if not incapable of — actually conveying anything, especially a person’s internal experience. Edmond finds that the fault lies in language itself — not even poetic language is sufficient, as language as a system is inherently flawed, much as Stein theorized. However, whereas Stein called for the destruction of language, grammar, and convention in works such as “Poetry and Grammar,” Edmond chooses instead to work within the standard structure of language itself as well as conventional formal containers for arranging language, subverting and inverting these systems, rather than destroying them, in order to expose the flaws inherent in them.

9

In this way, Edmond crafts twists and turns of language, showing how quickly a word can move and transform into another word by interpretation, manipulation, or simple mistake. In “Tender validation,” Edmond opens by a direct statement of this dilemma: “there isn’t a poem which couldn’t have been otherwise / than it is.” As the poem proceeds, the audience perceives events differently than the author intended, reading “a symptom of poor maimed suffering… as ecstasy.” This change in perception alters objects and events themselves, “and before long this photograph of love / is what connects them [the reader] to us [the speaker].” Agency is almost entirely in the hand of the perceiver, not of the portrayer, who finds “it is they who have given.”

10

Edmond, like Stein, moves the power from the writer to the reader; unlike Stein, he does not make radical moves in order to obtain power again. In “Poetry and Grammar,” Stein laments that conventional language, particularly “correct” grammar and punctuation, keeps readers from deeply engaging with a work and therefore fully understanding, as well as taking responsibility for, what they read. Edmond also hints at this idea, but the reader’s power, in his collection, is not a dangerous and dividing power but is, instead, what can unify us as human beings.

11

In order to explore this idea, Edmond makes use of analogue forms to look beyond the small scale of letters and punctuation points to the molds we use to hold language themselves. In “Album of the hour,” Edmond uses the form of a music review to show how “the singing is always its own subject” — in other words, every act of language is about the act of language itself. This, for Edmond, is especially true of artistic acts of language, “performative speech acts” which declare themselves as artifact by their mere existence: “from the first sound the song says I am song and means you will now read me as song;” therefore, it is the manner of singing, and not what is sung, which is important.

12

Here, Edmond turns again to Wittgenstein’s duck-rabbit: art is the form through which one expresses “your life, your dreams, your bad emotions, your weak visions;” however, art aims at beauty by its very nature, and by its very nature is thus “noise instead,” as “[t]hat at least contains delight.”

13

“This one that one,” a poem in the “Complication” section, serves as a culminating illustration of the illusory nature of meaning in language systems. Edmond presents a series of shifting, non-specific modifiers in the form of a dialogue between two characters who cannot understand or identify the “this” to which the other refers. Edmond continues to develop the idea that art is a failure because it fails to communicate the content it seeks to represent. He speaks of a character who “wanted to write. So you did you did. But it came out wrong.” Such a forced crafting of language communicates nothing but its craft. True representation is natural, spontaneous, and, ultimately, incommunicable: “You housed in your ears a melancholic trumpet sound no one else could hear. You just had to touch your nose and it started playing. Enough said. Don’t tell about that.”

14

Here, Edmond implies that real representation may be possible, but not communication, and not through art — though, again, the reader is at the same time aware that Edmond communicates these ideas through a carefully-crafted piece of art in a conventional form.

15

Edmond moves from complication to revelation in “Miniature” by depicting the frustrating paradox that one can never truly communicate experience to another, even — or especially — through art, poetry, and dance. We are nevertheless driven to communicate, “pestered” not only by a “naked beauty” but by the desire to “put it in a box,” a desire we can never truly comprehend, control, or complete, which ends in “this very irritation / with the dance.” Both the reader and the writer are left wondering if we are “naked on the outside / and naked too within.”

16

For the Modernists, such paradoxes led only to alienation, to an existence in which we all wander, helplessly and hopelessly apart from one another, unable to communicate or relate to each other. For Edmond, however, there is hope, and that hope lies in the very shifts and slides of language which also frustrate and paralyze the speaker. In poems such as “The animals of the bed,” Edmond twists conventions of language and form in order to jolt the reader out of complaisance. In a theatrical script, two characters speak in their bedroom, continuing their calm conversation as “Two turtles descend on strings and nestle in the pillows,” a subversion of expectations in which the reader experiences both the everyday and the otherworldly in one. The slightest shift of perception can turn the expected into the artificial. Here, Edmond extends the paradox which before related to acts of language and to art to the very concept of normalcy itself: life itself is a staged artifice, though we may pretend it isn’t. Every human act is an act of performance, part of the ritual we perform every day to bury and ignore the fact that the slightest shift in perception can prove the world is far from the normal.

17

When “[a] rabbit and a walrus hop and flip up the sides of the bed and flop onto the duvet” and the chorus of animals sing “Woo woo sshh sshh,” the couple simultaneously declare that it is “[t]ime to turn out the light,” to act out their daily ritual and submerge their very ability to perceive in darkness instead of acknowledging the absurdity of their situation. It is the theatrical curtain, however ― the very structure which forces an audience to suspend their disbelief and, for the duration of a play, perceive artifice as reality ― which has the last word. “[T]he curtains come crashing down, engulfing the couple,” and, “[t]o make sure it has the last say as it should, the Theatre Curtain girds itself in its own drapery and dances a fabulous finale, ringing itself down to thunderous applause.” The curtain states that “Frankly I feel upstaged by these anthropomorphic curtains which are really nothing more than mere stage props.”

18

Human perception plays the same role as a theatrical curtain, as each person attempts to maintain their sense of normalcy; this is ultimately flawed, though, as the slightest shift can shatter our sense of normalcy, and artifice is always exposed. However, Edmond presents this not in terms of destruction but as possibility, as each shift in each person’s perception creates a new and vibrant reality. Through his use of analogue form, Edmond allows the reader to perceive this possibility as something to be celebrated: the theatrical curtain will always fall, but it is the curtain, which creates the end of one perceived reality and the beginning of another, which receives the audience’s “thunderous applause.”

19

Edmond’s use of theatrical structure is therefore not merely an extension but a revelation of the text’s ideas, and the “Revelation” section continues to explore the great power perception has to shape reality. “Folk song” presents everyday objects, from barber chairs to shrouds to chewing gum, in the same light as stage props. Props, like Hedda Gabler’s infamous gun, are carefully chosen for their meaning and appear on stage only if significant to the play’s “reality.” In “Folk song,” everyday objects exist and appear for the same reasons: things exist because we have chosen to make them exist, and things only exist for us through perception and interpretation.

20

Edmond’s speaker perceives a chair in terms of what the chair means for him, as something made for him to sit on. Therefore, the chair is at once an independent, purposeless and will-less object as well as what this object is perceived to be in terms of its potential for use: “the leather on the chairs is shaped / to clutch your thighs / their silver frames are medicinal.”

21

Edmond’s revelation opens to show that this phenomenon occurs not only with objects but with time and action as well. Once perceived, an object, event, or moment exists as it exists in itself as well as in memory. Edmond writes in “Old Good Friday” of a speaker in motion on one night: “In its echo I exist / as long as it takes for the bike / to pass.” The speaker, the object, and the moment move on — but, at the same time, as he is “heading out along Glengarry ridge, / it’s going nowhere / because it is perceived,” held as memory in the mind as frozen as photograph or film. Memory, in “A name,” “roll[s] / like a pearl lodges on a collar-bone / with light,” preserved and polished and beautified in its stillness much as a pearl inside an oyster.

22

Here, Edmond shows that shifts in perception can be preservative rather than destructive, and can lead to beauty rather than despair, as in “The ballad of incommensurate space.” Though “the dogs. . . .lolloped home hang-dog” and “the wind lost its teeth and sagged,” “still you hung above and night began to shine / the milky stars of love which keep you young / shone down on you” if not in the reality of the world, then in the equally real reality of the mind, the speaker’s “inward hanging eye.”

23

As Edmond’s linguistic drama progresses from peripety to catastrophe, Edmond begins to untie the theoretical knot tied by Peirce, Stein, and Wittgenstein. In keeping with the collection’s theme, Edmond does so paradoxically by tying together his ideas on language, perception, preservation, and art. In “Never enough,” the speaker turns again to perception in showing how a presumably inconsequential event — the loss of a jersey — can be immeasurably important, so much so that “[t]he lost jersey / has created a permanent imbalance / in the equilibrium of the universe.”

24

Again, it is not the thing itself which is important but how the thing is perceived — the emotions we attach to the object, and therefore the language we use in relation to the object, describes and defines its reality, so much so “that it was not the jersey itself / which was lost but / the desire for the jersey which had been found.”

25

Just as the duck shifts quickly to the rabbit, so does meaning. Triumph instantly becomes loss, as “[w]hen dreams come true what is / there left to measure the world with.” We can desire things and acquire them. Our dreams can come true. But when our dreams do come true, and our desires are met, there is no way to define success or desire or ambition or drive and, therefore, our world. In triumph, “[t]he gear shifts like a dream.” The winner’s world is a different world, but one in which “[t]he sky will look like this tomorrow / and the day after,” and the speaker is forced to wonder: “So what do you do now you’re / just too happy to move?” Edmond answers with another unexpected shift: you hope to see “all that you had constructed in terms of / happiness dissolved. Only then can one be truly happy, as only then can one live in a definable, desirable world: “it’s this, that / dissolution, which you cherish now in memory.” Here again, what is often seen as the negative aspect of language instead offers hope: though divorced from meaning, language creates and fulfills a need of its own, as in “You all do know this mantle”:

26

most lamentation is solipsistic sensing in loss

only oblivion and no further chance of further loss

or of lamentation the lament being for

lamentation itself and therefore at heart (a metaphor)

having no being on its own

27

The language we assign to the word reflects how we perceive the world; therefore, it creates the world. Language, art, representation, memory, beauty: all can bring us back to the world, reminding us of what we desire, what we remember seeing as beautiful. And language, art, representation, memory — all of these performative, defining acts — have a value in and of themselves. The representation of a thing can be more beautiful than the thing itself, as the mother discovers in “Of the nature of nature” when she sees a portrait of the son whose very words “[make] my blood boil”:

28

it was love at first sight

and it was him

by some coincidence more him than he had ever been

and I knew how ridiculous I was

to love the painting more than the boy

29

Here, Edmond moves beyond the Modernists’ dreary theories about art and language and alienation to posit a thought so hopeful as to grant great power to human hands: perhaps we don’t need to be turned to the real world. Perhaps there is no real world to turn to after all. Perhaps we, like the mother, love the representation and not the person because the person changes so much and so often — like the son, who says “I can’t be nobody can I / if I’ve become someone else so many times” — that language and art preserve goodness and beauty and therefore are to be valued as much as, if not more, than the illusive, constantly escaping and abating “real world.”

30

The drama reaches its resolution by arriving at “The Gates of Paradise,” a short theatrical scene in which Henry Miller attempts to gain entry in heaven, still composing, describing, and naming: “She sat in the chair with her legs up… not a stitch on… did I tell you that she looked like a Matisse?” The Immigration Officer asks him to “look into the machine” and, upon testing Miller’s perception of the world against what he actually saw, finds that the visions “[do] not match.” In order to enter paradise, Miller must take out his eyes. Upon doing so, he exclaims “I’m free, I’m free!”

31

Heaven, then, is a place of rest and relief which can come only in the absence of perception. Freedom, Edmond suggests, is the ability to live outside of perception, and therefore without assigning meaning in a world where meaning shifts and slides by the nanosecond. Heaven blesses us by freeing us from vision and therefore from responsibility and change, and by allowing us to exist in a world where things — including our own selves — don’t look like things, don’t exist in terms of relations and assignations of meaning and therefore do not exist at all — but are things, real and whole and meaningful in and of themselves.

Emma Bolden

Emma Bolden’s chapbooks include How to Recognize a Lady (part of Edge by Edge, Toadlily Press), The Mariner’s Wife (Finishing Line Press), and The Sad Epistles (Dancing Girl Press). She was a semi-finalist for the Perugia Press Book Prize and a finalist for the Cleveland State University Poetry Center’s First Book Prize and for a Ruth Lily Fellowship. She teaches at Georgetown College and is poetry editor of the Georgetown Review.