| Jacket 40 — Late 2010 | Jacket 40 Contents | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 10 printed pages long.

It is copyright © Tony Baker and Jacket magazine 2010. See our [»»] Copyright notice.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/40/r-griffiths-rb-baker.shtml

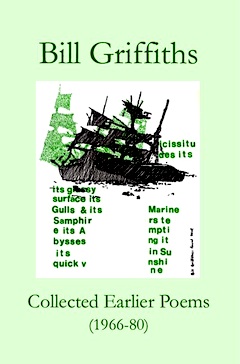

Bill Griffiths

Collected Earlier Poems (1966—80)

reviewed by

Tony Baker

Reality Street, 2010, ISBN 978–1-874400–45-5, 368pp, price UK£18

1

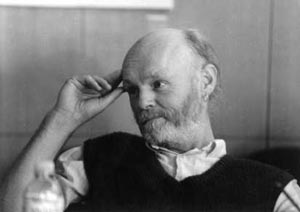

Bill Griffiths was one of the most original, baffling and brilliant poets to write in English in the last 50 years. Indeed he was original to the degree that it was perhaps hardly in English that he wrote: he created his own language. If it usually looks like English (he freely throws French, German, Latin, Romany into his mix) the more you hear it, the more it sounds simply like Griffiths. It means like Griffiths. He had a way with words — as Thelonious Monk had with notes — that’s instantly recognisable and utterly impossible to convincingly imitate. Like Monk, Griffiths’ signature was written across his life. What Monk could do with wearing a hat, he could do with preparing a roll-up. Both were so entirely themselves that before ever you get around to trying to fathom what’s happening in their work you witness its authenticity. It stands alone. Monk sounds like Monk: put the work of a thousand poets in a pile and burn every archive, you could still find the Griffiths amongst it.

2

Griffiths was a bundle of contradictions. With love and hate tattooed across his knuckles — a legacy of his biking days — you might have anticipated a temperament of violent oppositions and yet you encountered the calmest, most attentive of demeanours. He took inspiration from, and knew familiarly, people whose lives were precarious and marginal, who were sometimes barely literate in conventional terms, yet he created a unique literature from the contact. With Bob Cobbing, Michael Chant and Paula Claire in Konkrete Kanticle he performed as an unhesitating improviser yet, though he was a skilled musician, he took very little interest in musical forms based on improvisation. He liked Brahms, not blues. He was at the very least a good pianist with a profound knowledge of the piano’s history, but his taste was for 19th century instruments (1850 was a new-ish piano in his scheme) which were sometimes barely playable.

3

Accomplished and well-informed as a scholar of the complexities of early poetries in Britain, his own poetry — like his drawings — could at times seem as intuitive or naive as a local, folk art. He was a radical avant-gardist yet scarcely any of the precedents that interested him were to be found amongst the practices of the various Modernist poets of the twentieth century. He had a simplicity that was both disarming and disorientating; he listened without prejudice and argued with rigour. He talked as knowledgeably about football or bread-making as the operas of Mussorgsky.

4

As a publisher (his Pirate Press was enormously productive at different times in his career) he was both insistently homemade (his books were often handwritten and explicitly excluded from copyright) and alert to new technologies (he employed microfiche and web publication years before either were commonly exploited). Gently spoken, monk-like in his patience — in the few contacts I had with him I never knew him rushed — on the page his creative energy hurtled irrepressibly, anarchically and at times angrily, in all directions. A solitary man who lived on his houseboat or, in the last decades of his life, in his modest terraced home in North-east England, in all the tens of thousands of words that he wrote, although friends are often present, I know of hardly a hint of any intimate relation to another soul, man or woman; yet no poet has so thoroughly grounded his work in meticulous attention to the speech of others. A social historian, his inner integrities made him a nearly asocial man; you enjoyed his company but not his society. He conveyed a Rousseau-like belief in human nature — or perhaps just ‘nature’: there are animals or plants on nearly every page — that didn’t reject conventional structures so much as appear never to have a pressing need to incorporate them. And yet, while few men ever had less concern for mannerism, his manners were unfailingly courteous.

5

These qualities combined to make him a visionary of the ordinary. He brought an alchemy to bear on the unremarkable that transformed it into glittering stuff.

6

Most of the environment is locks.

A lock about Sea Rocket as big as a toilet door.

A rook over the Umbelliferae as tight as a baby’s pram.

And when they lock, they block.

7

These are the words of a man unafraid to set down exactly what the imagination offers, and they’re typical of page after page. Griffiths appeared so free of pretension and so seemingly unconcerned with how others might judge him that his words roamed easily amongst their own truth however it presented itself. While often hugely ambiguous, there’s rarely a tone that seems ambiguously poised for such tone belongs to a realm of social nuance that he bypassed. His words occupy a present tense of nearly animal being. A rook is a rook, is a thing that pecks. His metaphors can have a startling aptness. Where did he find anything so unlikely as “tight as a baby’s pram”? yet the image has an almost botanical accuracy. The music of the lines evolves with a geologic inevitability — a low rumbling so sure of itself that its echoes and parallels and rhymes embed a structure in the ears before you’ve had time to register it. He plays with words but his plays on words never seem like clevernesses.

8

A ‘lock’ is a passage from one stretch of water to another, or a security device with a key — a highly evocative word then for a poet of houseboats who had reason to know more about the impact of prisons on a life than many. But this doubling of sense occurs not as a witticism. Indeed the italicised is of ‘Most of the environment is locks’ explicitly rejects the idea. He is simply making a statement of perceived fact. The pun occurs, uncomplicatedly, in the spirit of observed evidence. Except that, by refusing the sort of slippage of sense by which a pun usually works — Griffiths was never aloof from his material and quite free of any need to be thought witty for its own sake — the word ‘lock’ acquires its own uniquely Griffithsy resonance.

9

Not least of the originalities of Griffiths’ approach to putting words together is his readiness to think of any manifestation of a text as provisional, rearrangeable and openly plunderable. For all the authority of their impact, his words could mask their origins as thoroughly as he himself could mask aspects of his own life.

10

For this first collected edition of his earlier poems, Ken Edwards’ Reality Street imprint has called upon Alan Halsey as co-editor, one of the very few capable of manoeuvring through Griffiths’ textual minefields. The task was to ‘collect all of Bill Griffiths’ poems, in largely chronological order’ up to 1980 while taking into account that he ‘was often cavalier with his work, fond of taking lines, stanzas and longer sections from one poem for transformation in another’, a practice that Halsey describes without blinking as ‘inevitably creat[ing] obscurities and anomalies in a retrospective account’. Anyone concerned to learn more about just how complex the editing process must have been should read Halsey’s detailed description in a forthcoming essay (“Abysses and Quick Vicissitudes”, in Mimeo Mimeo, 2010). Since Halsey focuses with particular care on the status of Griffiths’ texts and not on his own travails, The Salt Companion to Bill Griffiths (ed. W. Rowe, Salt, UK, 2007) should also be read by anyone seeking both an introduction to Griffiths’ work and an idea of how he himself could be simultaneously illuminating, non-proprietorial and misleading about his texts.

11

Yet the remarkable thing is that, however essential to the editor and no doubt the scholar to have some fogs cleared, such extraneous information remains essentially extraneous to the reading. Griffiths writes with an intensity that’s riveting and that operates irrespective of how much of his material — its sources, references and treatment — one recognises. This is very hard to explain but I think it should be acknowledged because the tenacious reader will experience it: Griffiths’ writing almost never fails to be compelling even though it very often appears difficult, to say the least, to know where he’s coming from.

12

Quite often I confess I haven’t a clue though it’s not certain that Griffiths was aware of his opacities and it is certain that in his own mind his writing was specific and referential because he would quite readily offer elucidations if asked. Halsey has plausibly suggested that Griffiths was perhaps ‘so absorbed in his peculiar studies that he didn’t really see how much [someone else] could be left on the outside’. Whatever the case, this is the kind of thing the reader has to deal with:

13

Ictus!

as I aint like ever to be still but

kaleidoscope,

lock and knock my sleeping

14

Griffiths was 22 when he published these lines, nearly the first he allowed to surface in public and, for readers who followed his career, likely to have been the first they were aware of. No beginning since Beowulf was ever so striking as the ‘listen up’ of those first five letters. He seems to have ducked the need for any early period of imitation and entered on a career with the stamp of his voice already clear on the page. The lines are in fact the first in a poem that itself is part of a series entitled Cycles whose formal procedures reveal how Griffiths was clear about his directions from the outset. The series forms a cycle both in the sense that it’s a suite (like a song cycle, though the particular order of the poems may not matter) and in the way that the lines within the individual poems are grouped into little batches (whose order equally may be mutable) that fold in and turn upon themselves. In this respect Griffiths’ lines resemble the coloured chips of a kaleidoscope as they reshape and reform in a mobile, permanently recycled sort of congruence.

15

And what are we offered here? A first word, straight out of Latin, that might send a reader scrambling for the dictionary, where he or she would find that ictus refers to an accent that falls on a particular syllable, from the Latin, icere, to strike. So Griffiths is announcing a poetry specifically of accent, with its roots in history; that is, if you will, a poetry of weight not syllable count (in the way of British poetries that existed before metre was imposed on them, following continental models, after the Middle Ages).

16

But the exclamation mark alerts us to the fact that this is a voice, not an allusion to an idea, so that ‘accent’ also evokes the accentuation of local speech, which is exactly what the second line gives us.

17

The single word of the third line, ‘kaleidoscope’, a 19th century invention out of Greek, tells us how the lines are meant to work (and I think anticipated Griffiths’ methods right to the end of his life); and ‘lock and knock my sleeping’ illustrates how the accenting of his kaleidoscoping words was to organise his lines (and more elusively suggests the visions of dreaming that often preface old British poems). Four lines then: the first from a written language that no one speaks, the second from a spoken language you might not expect to see written. The third is a neologism derived from yet another language. The fourth does what the others prepare you for. Griffiths knew he wasn’t ‘like ever to be still’ and set down in sixteen words at the head of his first generally known poem — in so far as he’s known at all — the elements of a life’s work.

18

To give an idea of what these elements could generate, here’s an entire poem from this collection:

19

Vance’s Clugel the Clever receives

a small Tribute of Admiration

When woke

athirst FOUR fiery gas’s as

hair-ruby

magnet-knee

broach of roof

is: shoulder-free.

certain.

wires, choirs, pyres, fliers

are are

mo’ magnified thru and by.

the blast:

winds, winds’ caves, sacks

sagg’d,

cool, are’s, lungs, child

‘at is in

these shreds across

- like a labour — sky.

No longer possessed, Glory –

sure, shoal, speak-unlike,

steer or all-bake, t’ward beak-ball.

A sunny blank.

all

allabout

tearstained rows of iron

clinch

and change (with you)

20

This may be an extreme (though not really atypical) example and it may be that the earlier poems, now that we have them in an approximate chronological order and can see them in the context of Griffiths’ development, tend to be the most opaque that he made, but if the reader is discouraged by writing such as this then Griffiths is going to prove hard to swallow. His numerous formal inventions, followed through with the care of a laboratory technician, often present equally nuggety stuff to which we get few or no clues. Just getting this poem into a Word document sends the automatic corrector into apoplexy; ask Google what, or who, Clugel the Clever might be and it thinks either that I might be looking for a type of thoroughbred horse known as a ‘Belgian warmblood’ or it invites me to check my spelling.

21

I can recognise shapes here — the rhythmic parallels, the alliterations and rhymes — and the virtuosity with which Griffiths shifts accents to keep the lines alive and kicking; and I can register how he gets energy from words often of one syllable that are brightly resistant to abstraction (even his invented compounds, as ‘all-bake’ or ‘beak-ball’, are often only aggregates of single syllable words stuck together in a knot). These are things that frequently characterise Griffiths’ poems. But I can’t get any nearer the references in the poem (though readily believe that they exist). The poem nonetheless has a sort of atavistic force. It makes the reader part of its ritual by invoking the real in a liturgy of spellings out.

22

It would be easy to underplay the degree to which Griffiths had a literal sense of the magic of words. He had studied riddles and spells and understood that, in a primary sense, to name a thing grants power over it. Words came to his mind as vivid, even dangerous, charms. Their interactions on the page trace paths that fizz like fireworks across the sky at night, arising from the dark and falling back to it. Bound into whatever they say there’s a luminous, numinous, awed sense of their power as raw matter working in and on the world. It’s part of the wonder of his writing that he sustained this feeling for words unclouded throughout his life. He could conjure up compelling texts because he believed in the magical potential of his imagination as a child believes in the figures of play. And in this respect his imagination was at one with all things that have their own particular way of functioning. As he wrote in “Toy World” (a poem collected in The Mud Fort), and we do well to think he meant it as simply as it sounds

23

All things that work

are fun.

There is incipient magic.

24

Nor finally is this all, for there’s a footnote to this reading of the poem: the magic spelt out in “Vance’s Clugel… ” will throw its dust of fascination in the eyes of many more than me. Having written the above paragraphs, a correspondence with the editor led to a chagrined apology, for as Paul Quinn was led to point out after the Earlier Poems had been published, ‘Clugel’ is in fact a mis-spelling.

25

‘BG was obviously reading a lot of SF and Fantasy lit during these early years — hence the Tolkien, P.K.Dick, Jack Vance references — not usual resources for collage/poems in the modernist line — especially not when these were written. Anyway, RE: ‘Vance’s Clugel the Clever receives a small Tribute of Admiration’; Jack Vance’s character (from The Eyes of the Overworld) is actually called Cugel the Clever. I assume this was a typo in BG’s original text rather than intentional, but I thought I’d point it out — sadly, divisions of intellectual labour (which BG resists with zest) mean many Griffiths readers won’t have read Vance. And vice versa.’

26

True, I’d not heard of Jack Vance nor had the editor, but the confusion is instructive: it illustrates not just the difficulties (if that’s what they are) of reading but also both how distinctive Griffiths’ textures are and how remarkably effective the editing has been that we aren’t led to suspect chimeras of this kind. There must surely be other doubtful versions that have slipped through the net of silent correction but, even if they reorient it when one knows better, they simply don’t trouble the reading.

27

For Griffiths has an unparalleled capacity to convince. You sense that only an absolute authenticity — an imagination locked determinedly on the concrete however idiosyncratically perceived — could so consistently avoid lame or rhetorical padding. He sustains the reader’s attention because he’s a craftsman working his materials truly to his own measures: he makes them ring true. He can be obscure but he isn’t obscurantist. He hides nothing from us even if we can’t be sure what’s on offer. ‘Each order’s a/puzzle./Maybe I work my own work out’. As the ‘maybe’ here suggests, the reader is never excluded or berated for what he or she doesn’t know. The writing’s as available as a skipping rhyme. And if it can struggle with its own solitariness

28

sometimes

I think it

you don’t understand me any more than I do you

29

it’s the very loneliness of the path it treads that opens the way for the reader. It also opens very great and unique beauties that will stand comparison with any in English poetry and which are now available in a substantial volume whose editing — a well-nigh impossible task to complete satisfactorily — is intelligent, unobtrusive and clear. These are achieved beauties derived from an integrity of vision whose sweep takes in the immediate prospect by doing simply, sadly, comically, puzzlingly, and very engagingly what it says — ‘looking to see what is out there’.

30

A rich jigsaw’d gorse

ruby / lamb-yellow on a sandy land, & dry lunch

surrounded by a 100 wheeling dinosaurs, at

an aviary

gaunt legs of rubbish, pliant of bone

set up working under the rainarch

looking to see what is out there

Tony Baker

Tony Baker was born in south London in 1954 on J.S.Bach’s birthday. He studied piano and composition at Trinity College, London, literature at Cambridge University and subsequently completed a PhD on William Carlos Williams at Durham University in 1982. Since then he has worked mainly as a musician and ecologist. He has written a book on the history of mycology and co-authored another on creative work with autistic children. He edited the poetry magazine Figs from 1980–89. With a home still in the Derbyshire Peak District, since 1995 he has lived amongst the vineyards near Angers, France.