| Jacket 40 — Late 2010 | Jacket 40 Contents | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 4 printed pages long.

It is copyright © Chad Scheel and Jacket magazine 2010. See our [»»] Copyright notice.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/40/r-jones-jill-rb-scheel.shtml

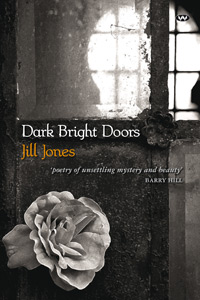

Jill Jones

Dark Bright Doors

Wakefield Press, 2010, paper, 96pp, ISBN: 9781862548817, AUD 19.95

reviewed by

Chad Scheel

1

The publisher’s comment to Dark Bright Doors describes Jones’ work as “self-critical and very present.” The self, as it locates itself within Jones’ work, is not one which strives to be in the present — because it wants to be — not zen striving — but because it feels obligated to be. The poetic self which stabilizes within a grasp of objects in the material world is here transformed to one which loses grip on those objects and all personal connections. The book’s enscription states “Contact/is/the art” and each poem reaches toward that contact. Some fail (intentionally — these are brilliant poems) and others begin to make their way toward a resolution in that which is beyond the poet.

2

The difference between that self and other disconnects of identity is not that Jones delights in the disconnect and thus exploits it, nor is hers the self in denial and leaning toward simplistic linearity. The attempt becomes one of social implications — for the poet, a question of the work’s ability to make those connections beyond the poet’s life. Dark Bright Doors opens with “Oh, Ground” (note: not ‘O’ Ground. This is no ode, instead, a forgotten entity.) containing these stanzas:

3

What do I do

without any legs

Walk on shadows

simulacra

…

Ground — where

are you, if

I step on you without feeling

4

as a self that lacks the necessary tools. From the beginning, the book makes use of vacancies as an barrier. Through various forms and modes, Jones attempts to fill those spaces — sometimes by revising a different self, sometimes by giving up entirely. In “At Large,” Jones writes: “but now, bypass the knife/the gate, bypass yourself”.

“Sorry I’m Late” uses the title’s irreverent timing to make light of situational gravity:

5

A truck jack-knifed the particulars

There was a smell of old gas

…

That prick in the garden

We forgot to fill out the form

Celebrity drug disasters were drifting in our channel

6

It is in this poem that Jones begins to examine the self and language’s ability to withstand the fleeting nature of pop culture. It seems unclear if “channel” refers to television or, because of the verb “drifting” something more lasting, water. The concern that typically arises for a poem that places itself within such a current locale is that it stale dates itself. In Versed, Rae Armantrout’s writes “New”:

7

The new pop song

is about getting real:

“You had a bad day.

The camera don’t lie.”

8

The concern that typically arises for a poem that places itself within such a current locale is that it stale dates itself. (I wonder — with Armantrout’s reference to Powter — will later generations be able to read that poem the way the current generations read Zukofsky?) Rather than run this risk, Jones buries these notes so that the poem might function without the culture context. References to tiger [Woods], Bob Dylan (“blond on blonde”) and even Princess Leia occur, with only the last being capitalized and allowed to stand out.

9

“Yeah,Yeah” leans toward engaging in sarcasm, a quick read reveals retort: “yeah/and the mirror is the dark, brilliant.” However, Jones has again played juxtaposition in the line unit into something which is contrary to its initial read. “Yeah, Yeah” isn’t the apathetic Paris Hilton yawn nor is it a Lil’ John exclamation, the poem itself is the uncertainty — the pause — between the yeahs that takes it beyond mere pop culture to something of larger affirmation. (A defense of Armantrout: the references are throw-away as most pop culture is, the poem is precisely the phenomena. Better yet, it’s Interpol’s “The New”: “I can’t pretend/I need to defend/some part of me from you.”)

10

In this sense, the allusions are part of the landscape. In “Mystery Train,” Jones sees “riding round all night/everyone looks like Elvis”. However, like Armantrout, Jones turns to these allusions when the self is defining itself as something larger, culture or society as a whole.

11

Jones’ finer — or at least more stable — moments occur in poems where the specifics of location replace the philosophical materials of her longer poems.

12

“Regarding Pain” is juxtaposed haiku, 3 parts evenly spaced on the page which conclude with “shawl of rain/on street-brown buildings/no spare change” which makes its social concerns known within a poem more singular. Here, vacant space is welcomed and as Jones moves toward objective specifics and away from societal observation, the books most powerful moment occurs. From here, the poems develop the missing legs of “Oh, Ground.”

13

“High Wind At Kekrengu” allows the self to look outside, and here the poet finds the materials that will last beyond the book:

14

surf

talking infinities

gulls riding

what’s left of the air

15

Jones here has turned to landscape, but again maintains her deft use of line and stanza unit so that “surf/talking infinities” is one part natural sound and another part conversation (though “surf/talking” immediately calls to mind the slang speak of “Yeah, Yeah”). This poem is more assured, confident than “Oh, Ground” or “Sorry I’m Late” as its materials will last longer than the “celebrity drug disasters.”

16

As maligned as the “I” has been, Jones’ collection contains demonstration that that “I” is better suited when it is singular. The self, when no longer trying to carry the “we” is able to grasp the particular and, as Jones states in “Figure”: “Look at everything/with eyes/skirting the obscene.” Near the book’s close is “Notes/With Selves,” a list poem in which Jones reconciles the issue by cutting time across location:

17

self in weather

self with the owls

self that’s gone away

…

self and results

wet rails

keep self moving

18

This is the self trying on location as a means of making connection. It is no longer concerned with the “we” because they’re somewhere else. Even the self of the previous moment is gone leaving the poet to continue seeking connections in the next location, truly being present. Lest poets too often take on scope larger than their (or anyone’s) means, Jones provides an example of the poem made and defines the method in “The Wandering Poem”: “Doing, leaves, birds. This world.”

Armantrout, Rae. Versed. Wesleyan University Press, 2009.

Chad Scheel

Chad Scheel lives in Scottsbluff, NE with his wife and son. His poems have appeared or are forthcoming in freefall, Poetry East, elimae, Arch, and Anemone, Sidecar, and Indefinite Space.