| Jacket 40 — Late 2010 | Jacket 40 Contents | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 9 printed pages long.

It is copyright © Vincent Katz and Jacket magazine 2010. See our [»»] Copyright notice.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/40/r-lauterbach-rb-katz.shtml

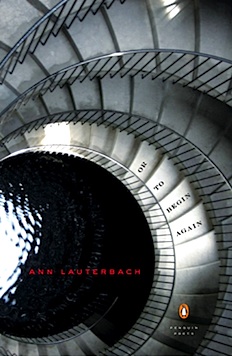

Ann Lauterbach

Or To Begin Again

reviewed by

Vincent Katz

Paperback | 8.26 x 5.23in | 128 pages | ISBN 9780143115205 | 28 Apr 2009 | Penguin

Ann Lauterbach is Ruth and David Schwab III Professor of Language and Literature at Bard College. Her work has received fellowship support from the Guggenheim Foundation, the Ingram Merrill Foundation, and the John D. and Catherine C. MacArthur Foundation. She has published six collections of poetry, including If in Time: Selected Poems 1975-2000.

1

Ann Lauterbach’s most recent book of poems, Or To Begin Again, seems about to complete a sentence when combined two earlier titles of hers: Many Times, But Then and And for Example. The sentence might read, “Many times she wandered over to the stair but then returned to the divan and for example picked up the crossword puzzle, or to begin again, she would go to sleep.” Each reader of Lauterbach may make up her/his versions, or different versions on different occasions, but there is always the temptation, more, the necessity, to fill the tantalizing blanks left in these titles. As with all good titles, these epitomize the texts found between their covers.

2

The experience of reading these titles is, fractal-like, the same (or very similar to) reading the poems they stand for. The titles clearly work by elision. They open up fields that are not present for the reader but which are nevertheless enticing. “Primer of elision,” a phrase from “The Scale Of Restless Things (Fra Angelico)” in Or To Begin Again, could serve to describe the book itself, if we think of primer not as textbook but as prime-mover, instigator, causing readers to fall into patterns similar to those it sets in motion.

3

The table of contents reveals a tri-partite environment. This feels comfortable — let’s settle in. Even “A NOTE TO THE READER” before we begin our journey: “When a proper name appears in parenthesis after a title, it often indicates that the poem has been drawn from an encounter; notations written as I walked through an exhibition, or listened to someone give a talk; or from my reading of an essay or poem. Throughout this collection, I am interested in differences between spoken utterance and written text.” This is important, though it must be forgotten as soon as we turn the page. Once we start reading the poems in Or To Begin Again, we are taken on a ride that causes us to jettison all instructions, admonitions, and simply give ourselves up to the experience. Yet we remain fully conscious the whole time, aware, at times cruelly, of how much there is to know in these poems, of the distance between writing and reading, or between reading and speaking, between our private experience and that of any other person, living or not. And when the ride comes to an end, we are aware that she is interested as well in similarities between utterance and written text.

4

To return to the table of contents: one section comprising ten poems, four of them with proper names in parentheses (Thoreau, Blanchot/Mallarmé, Hélène Cixous, Saint Petersburg); one central section composed of one poem, “Alice In The Wasteland”; and one final section composed of seven poems, three with proper names in parentheses (Fra Angelico, Bill Viola, Gego) and another with a proper name in the title proper (“Elegy For Sol LeWitt”).

5

The first section of Or To Begin Again exhibits exemplary diversity. It begins (again) with “Bird (Thoreau),” a poem in four sections composed of two-line stanzas. Next comes “Dear Blank,” in lines of varying length grouped together into long, rangy stanzas. That is followed by “Ants In The Sugar (Blanchot/Mallarmé),” which is where things start to loosen up. It is as though the singer has gone through her first two numbers, the first one a standard, always a crowd-pleaser, gotten her vocal chords limber. In the second number, she has allowed herself to stretch out, really belting out a verse or two. Now, she is ready for the performance per se, the part people are going to take home with them. The names in parentheses are very significant (parentheses, unlike ellipses, including instead of excluding). Thoreau is one of our most compact writers, capable of such sentences as, “Sometimes, having had a surfeit of human society and gossip, and worn out all my village friends, I rambled still farther westward than I habitually dwell, into yet more unfrequented parts of town, ‘to fresh woods and pastures new,’ or, while the sun was setting, made my supper of huckleberries and blueberries on Fair Haven Hill, and laid up a store for several days.” I have been pondering the way words and ideas intersect. The ideas Thoreau broaches are seductive, but so, on its own, is his language, his “still farther westward” or “yet more unfrequented.”

6

I wonder if Ann Lauterbach sometimes reads texts this way. Her use of the names in parentheses is more than a shorthand for researchers; it serves a purpose in the poetics. That purpose is to recall the thoughts and words associated with the person noted. Returning to her “note to the reader,” we remember it is not only books and authors she cites, but also encounters, exhibitions, lectures. Being parts of the titles, the parenthetical names are more like keys than notes, i.e. we are not meant to look up references but rather to use the broad hint as an excuse to dive through an opening into an ever-widening expanse.

7

By the third poem, then, she is really singing, and the form of the poem starts to break apart to reference that openness of voice. Mallarmé is here, and so is Maurice Blanchot. George Craig writes:

8

Blanchot has devoted his life to showing that it is in writing, not beyond it, that the central human choices are made. This revaluing of literature he has pursued both directly, in his more general essays, and by way of his readings of a number of writers, two of whom have perhaps paramount importance: Mallarmé and Kafka. Blanchot’s contention is that the stakes of literature are dauntingly high; the writer writing must come to terms, in one direction, with the tenuousness and narrowness of his or her hold on language, and, in the other, with the comparably overwhelming realities of silence and death. And so his exemplary figures are those who, like Mallarmé and Kafka, both remain wholly aware of these stakes and yet venture into the space of writing.

9

The crux is in the being aware of the stakes part. What are the stakes, and is Ann Lauterbach aware of them? I am going to posit an answer: she does not need to be aware of the stakes — at least the stakes as posed by Craig — because she is pure. She goes on her nerve, I am almost sure of it. The proper names are, well, not a smokescreen, but maybe an opacity. Before I was thinking they were expansive pools one could dive into and lose oneself in. Now I think rather they are paintings of those pools — the feelings they engender may be equally expansive but the real nourishment is going to be got from the poems themselves.

10

“Ants In the Sugar (Blanchot/Mallarmé)” starts out obediently on the left margin but soon begins shooting out the right, breaking rank, in outbursts such as, “Quickening, surrender,” “phantom aptitude,” “coming farther out,” “leans asking,” “Who has bagged the plot,” “who nags,” “as if it were a wall of light,” etc. This is actually a productive way to begin reading Lauterbach. Of course, we want to graduate to reading her line by line, as then we will be in a position to appreciate the ultimate — and casual — mastery that makes her poetry purr. In the second section of “Ants In The Sugar,” space is blown wide open. Lauterbach has learned from Olson, as she herself points out, and has an ability, unusual these days, to charge every area of the page of spread. In Lauterbach’s “spread out” poems, Mallarmé returns — the Mallarmé of Un coup de des jamais abolira le hasard. We finally get:

11

we

are

we

we wear

war

echo

12

In the final sections of the poem, the lines settle back down to the justified (and justifiable) left margin.

13

The poem “Nothing To Say” lies substantially at the center of the first section of Or To Begin Again. Prose-like blocks mingle with westwardly (and eastwardly) rambling phrases. The energy flow never stops. Here is a typical passage:

14

so it becomes

impossible to point or to deny, hurrying into it, arranged along a path, the division between let’s say heartbeat and thunder, or the alarm and Mahler’s songs closing distance in, or the stones and paper waiting to be inscribed with the arrival at the circle as it curves outward

split open

to reveal

the excess of a dream, we who had been speaking mildly to each other following collapse, sipping tea in the tearoom, there, sequestered against those others and their meridians on the chart, it was difficult in this setting to notice, although the waitress was an actress, her lips scarlet, but this was only the lure of

glamour, toned muscles of the arm, cleft above the thigh. Found her there again, again walking the horizon, where what was alive and what not alive almost touched, as moments touch, walking now with her sister on the other side of the line which is an illusion, the line, not the sister, she was there, among all the sisters, their chorale in the meadow, now turning, now following the path

15

This is very suggestive, and what comes to mind momently is the chorale of sisters at the end, and the meadow with its path, all of which puts me in mind of Sappho. Here, we seem to have a very Sapphic passage. The key words are “heartbeat,” “excess,” “the lure of glamour” — these give us the emotional tone — and the condition is very much one of physical nature — “split open” “to reveal” — the mild, sequestered ones are split open, probably, to reveal the excess of a certain person with the physical characteristics of toned muscles and a “cleft” above her thigh. They are walking and almost touching “as moments touch.” This open reading is not intended to explain the poem, only to show that, by paying close attention to its phrases, one finds them echoing and interlocking — or rather repeatedly locking and unlocking, in new iterations, with different possible readings. That to me is a key to Lauterbach’s method — composition not by field, though, as we have seen, she makes great use of the arena (or area) of the page, but rather composition by phrase.

16

Hélène Cixous appears, importantly, too, in this initial section as parenthetical basis to the poem “The Is Not That Is.” In “The Laugh of the Medusa,” this important Algerian-born critic and novelist states, “Censor the body and you censor breath and speech at the same time. Write yourself. Your body must be heard.” Her seminal essay “Coming to Writing” begins, “In the beginning, I adored. What I adored was human. Not persons; not totalities, not defined and named beings. But signs. Flashes of being that glanced off me, kindling me.” Lauterbach must find a kindred spirit in Cixous. As we saw in our brief reading of “Nothing To Say,” the body serves as locus for ever-igniting observation and re-observation. Because no narrative is begun or concluded, each phrase begins from immediacy, that is, from some bodily, perceptual, calling or inkling. This is not to see that Lauterbach’s poems are not intellectual; they are highly intellectual, but intellectual as music is intellectual, as Chopin for instance is, or as Mahler, in his songs, is.

17

There is more, much more, that one could elaborate — how “Realm of Ends” is a surprising poem of loss, “After Tourism” a reverie/love poem, and “Figures Move (Saint Petersburg)” an invention that sets the scene for section two of Or To Begin Again.

18

Section two is dedicated to a single poem: “Alice in the Wasteland,” a 30-page song whose musicality is ongoing and delicious and never devolves into complexity for complexity’s sake. Alice is a character in the poem; she begins by asking questions:

19

Why do shadows get longer? Alice asked no one in particular. It must

have to do with the angle of light, she answered herself, but this answer

did not make her feel confident. The question lingered anyway and

was added to by another. Does everyone know how to tell the difference

between a shadow and a thing?

20

A Voice answers her, and they begin a somewhat petulant dialogue, something similar to the kinds of discussion in Alice in Wonderland. Alice begins to read The Wasteland:

21

April is the cruellest month . . .

She stopped and considered what an odd observation this was. Alice had thought a

lot about the idea that

some things happen because someone intended them to happen, while

other things happen seemingly free from anyone’s volition at all.

She continued to read, hoping to find out why April is cruel.

22

It seems clear that reading more won’t help Alice find out, that reading itself is cruel if it pretends to give explanations. “Alice began to read again, but the words came out/confused and intermittent. Her mind interfered.” Because of the mind’s influence, the conscious mind attempting to control the situation, the meanings become discombobulated. This is immediately followed by the following stanza:

23

with dried

without pictures or conversations take the laundry in

over the Starnbergersee

what is that?

shower of rain for the hot day the pleasure of making

water the roses

in the colonnade in sunlight I have never seen a colonnade

of getting up with pink

I hate pink

into the Hofgarten.

24

There is more: lyricism, heartbreak, despair. Finally, there is Language, with a capital L, and words: “Following her, an incomprehensible jargon of something found in the jumble sale of /Language.” “I am only words.”

25

The third section of Or To Begin Again brings us back to form: the echoing couplets of “Echo Revision,” the open field of “Alone In Open (Bill Viola),” elegies for Barbara Guest and Sol LeWitt. The title poem, “Or To Begin Again,” is in 16 numbered stanzas, each except the last beginning with the words from the title.

26

It is in one particular poem in this section that we can, by some analysis, find how Lauterbach is working in these new poems. This is the poem “The Scale Of Restless Things (Fra Angelico).” It is written in an open-field frame, in 10 sections, each about a page long. The first thing that strikes one, on the first page, is:

27

pluck from vertigo

the shack’s

bravado

swept out to sea.

Save the O.

28

I made pencil lines from “pluck” to “shack” and from “bravado” back to “vertigo.” A vicious circle of the most delectable kind. I realized these words in Lauterbach’s poems work differently from words in most other poems. Their particular positions on pages are pitched, tilted, towards each other. She has a very acute visual sense of the words to the page, Mallarmean. Olsonian too, and the “Save the O” here seemed to me a plea for more Olsonian poetics in our schools.

29

Sometimes, single words stand out and can be read as a thread, apart from the safety of their lines. One section read thus becomes “halo,” “lily,” “pattern,” “hut,” “pinnacle,” “also,” “drops.” “shiny… perfection” became “refraction.” “The mercantile dressage at the core of the Rose” triggers thoughts of “Rome.” There is transformational power at work in these poems. The poet clicks into it fractally; micro and macro are firing simultaneously.

30

Continuing on: “primer of elision” could serve as a poetics. “on imminent foreclosures of the real” : that’s too close to home for some readers. “fury in stasis” : again a poetics (or a dogmatics, depending): tied to “primer of elision.” “flips” in “the past flips up” : “slips, zips.” “as if,” yes. “word of mouth” : “by ear, he sd” “unkempt sheets, etc.” Leading to another sexy scene:

31

Flirty filmmaker deceived I

and her ancestors, soiled her

party dress, whipped her torso,

led her across red rope at the club.

Made nothing absolute happen

32

“rope” brings back Rose (and Rome). “Nothing absolute” (italics AL’s) : a reading.

33

“In the film of the painting,/the zip zips open” : “the slip” “leave expression behind” almost in quotes. “I launched a scroll/in the misgivings of January,/after Rome.” Rose again, and rope. “girdled by fact” brings back “fury in stasis.” “scholars” makes one think of dollars. “She might have called it/a fool’s error” : fool’s gold. “Infidelity of the page” : on the page. “For new boots” of Spanish leather. “Error, a splash across a hem or cuff” brings us back to the poem’s opening phrase:

34

Error bloom

inadequate spent

35

“The audience is assembled” in auditorium dollars. “rumpled sheets” : “unkempt sheets, etc.” “moth… source… camera” chimera “herald”:

36

Pythia on tripod.

37

and a funny final couplet!:

38

“with the iPod attached to iTunes/all the numbers in play.”

39

I tried this brand of reading with an earlier Lauterbach poem — “Lakeview Diner” from her 1991 collection Clamor — and it worked like a charm. Pigment became pavement, outskirts skirts, and beginnings mornings. A paragraph was a photograph, the waitress turned into a witness, and reverence was evanescence. Elsewhere, in the poem itself, without any intervention from “a reader,” brief booty, a rag, the rag, “the numbered/scheme of things.” “brief,” “a leaf,” “ourselves delayed.”

40

I feel there is something in Lauterbach’s poetry that liberates the critic, allowing (or perhaps forcing) her or him to find a language that is appropriate to the freedoms she allows herself.

41

I went to hear Lauterbach give a lecture entitled “The Given and the Chosen” on February 11, 2010, at the School for Visual Arts in New York. The lecture was a work of art in itself, a performance, and when it was over, there was nothing left to say, just satisfied silence. It had a political component to it, distinguishing what she called “utopian possibilities” from the intransigence of the current political climate. At one point, she stated, “I like to digress, wander, scan.”

42

This is what has attracted me to Lauterbach’s sensibility, which comes across so strongly in her poetry, but also in her critical writings (collected in The Night Sky: Writings on the Poetics of Experience, 2005). She addressed issues raised in Jaron Lanier’s recently published You Are Not a Gadget and held up Oppen’s clarity of silence as an important counter-example to the endless chatter that is constantly clouding our awareness of essential issues, compromising our ability to act. It was empowering when she reminded the audience that “Givens go out of existence.” We are not bound by someone else’s definition of reality.

43

She ended with Emerson’s 1843 essay “Experience,” quoting his question, “Where do we find ourselves?” and affirming his sense of wandering. This emphasis on wandering has much to do with the quote from Thoreau that began this review. This is not terribly surprising, but it is encouraging, as was her statement about “Experience” : “I can’t recall what it says, though I’ve read it dozens of times.”

44

Finally, the silence was broken, and the audience began to respond verbally. This resulted in a number of zingers, Ann-isms:

44

“We are all so ferociously anxious about getting somewhere.”

“I have anxieties, but I don’t have positions.”

“I’m down with Jeff Koons.”

“Poetry is about having a conversation with the materials, not self-expression.”

“The givens are malleable.”

44

Or To Begin Again, we are left with satisfied silence.

Vincent Katz, Vienna, photo by Vivien Bittencourt

Vincent Katz is the author of ten books of poetry, including Cabal of Zealots, Pearl, Understanding Objects, Rapid Departures, and Judge. His most recent book of poems is Alcuni Telefonini, collaboration with Francesco Clemente published in 2008 by Granary Books. Katz curated an exhibition on Black Mountain College at the Reina Sofia museum in Madrid, whose catalogue, Black Mountain College: Experiment In Art, was published by MIT Press in 2002. Katz won ALTA’s 2005 National Translation Award for his book of translations from Latin, The Complete Elegies of Sextus Propertius (2004, Princeton University Press). He is the publisher and editor of the poetry and arts journal VANITAS and of Libellum books.