| Jacket 40 — Late 2010 | Jacket 40 Contents | Jacket Homepage | Search Jacket |

This piece is about 8 printed pages long.

It is copyright © Ken Bolton and Jacket magazine 2010. See our [»»] Copyright notice.

The Internet address of this page is http://jacketmagazine.com/40/r-myles-rb-bolton.shtml

Eileen Myles

The Importance Of Being Iceland — travel essays in art

reviewed by

Ken Bolton

Semiotext(e) / MIT, 2009. isbn: 978 1 58435 066 8

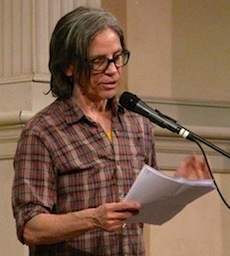

Eileen Myles, St Marks Poetry Project, 1 January 2010, photo by David Nolan

1

There are some terrific pieces in The Importance Of Being Iceland — Eileen Myles’ collection of essays — mostly the obviously ‘major’ ones. The title piece is one, ‘How To Write An Avant-Garde Poem’ is another, ‘Everyday Barf’, and a number more. ‘Iceland’ is remarkable: a journey, a charting of emotion and self-image, of insecurity, physical stamina, through uncertainty, exhaustion, elation, as well as being a meditation on ‘Americanness’, gender, the West, politics. It is never heavy or ponderous. In fact it is often funny. It is a narrative that is also a meditation.

2

Generally Myles seems, in her essays, to suppress agendas of argument and to attend to patterns of association and to a mapping of mood and even her physical state — of energy, of tiredness, of illness. At least it seems to be the interplay of these things that drives and finesses the work — a question of resistances, changes of gradient and adjustment of ambient feel. The ‘argument’ gets made even so. Sometimes it is enacted more than stated, sometimes arrived at as a verdict left to the reader to vocalise or pronounce, though Myles has brought us there.

3

This seeming indirection is to be applauded and is something the reader is grateful for: these pieces take us on trips and we accompany Myles and live with and through her. These are qualities the writing shares with her great collection Chelsea Girls — stories whose movement, unfolding, ‘development’, seemed almost muscular, like a series of reflexes, a pattern put in play, like a brief wrestling match, an argument, a coming to climax, or to growth or withering. The effect is one of grace, though we can assume Myles will have been, at times, lost and uncertain of where she was going while deliberately keeping this from being a primary consideration. If one thinks about it one can figure that cuts have been made at various points, or sudden wilful changes of tack been decided upon. But not very often.

4

On occasion this indirection — refusal of direction — does not result in sufficiently interesting outcomes. The college address given in ‘Universal Cycle’ goes well for a while and isn’t, finally, a dud, but I did get the sense of the writer’s underlying desperation as she pressed all the random combinations and failed to hear the ‘click’ of a closing combination paying out to save her. Here she relies too heavily on an innocent simplicity that seems forced: an act of wisdom — a wise, innocent magus for the young graduates. Corn.

5

The essays are pitched differently from one to the next. ‘Mr Twenty’, for example, you’d love to see appearing in the weekend papers. (That it can’t is partly what the story is about.) It posits the patriarchy’s continual reclaiming of the spotlight, all the spotlight. That is, if the word “difference” becomes a buzz word then the big end of town must ‘take it back off them’, take it from women, from the minorities, who are using it to such effect. “Politically correct” (Myles cites it as the one we all know) — it seems a good joke in lefty-versus-lefty in-house argument? Take it off them (who, after all, are ‘conspiring’), use it against them.

6

‘Mr Twenty’ is about that and, as well, about the marginalization of female experience: male experience is of interest, is regarded as of ‘general’ interest, women’s experience must appear only in women’s magazines. The piece is accurate — and pithy as it goes about it. Myles’ journalism is not what I most wanted the book for. But, while I would have thought I was more interested in her art and literary pieces, ‘Mr Twenty’ was a very good piece of a more public writing. Subsequently, as I read through the collection, I found that, within each of the categories and at each of the levels of pitch that Myles works, there are essays that are unarguably good.

7

‘Eye: The Poems Of Jimmy Schuyler’ is an essay of close reading of some of Schuyler’s poems — close reading, and accurate noting of entirely specific, ‘local’ effects, from word to word, weight to weight within the poems, and identification of their causes — and makes available genuine insight into Schuyler’s aesthetic and personal, human motivations. It is very, very good. I suppose some readers will prefer the Myles of ‘Mr Twenty’. One can’t say they are wrong. There is stuff in here for everybody.

8

But, this is my review — so to get back to ‘Eye: The Poems Of Jimmy Schuyler’. Here Eileen Myles also uses the opportunity to tell us valuable things she knows as a fact about Schuyler, putting these ‘on the record’ — for which the world will be grateful. The essay really is worthy of James Schuyler (which is saying something, I think) — and I am sure Eileen Myles would regard this estimation as praise.

9

I’ve enjoyed reading these essays. One comes to know quite a bit about Eileen Myles as the essays progress, and to like her. A couple of weeks travelling with her, reading an essay or two every day or so, means a kind of ghost Eileen Myles accompanies one, on and off, from moment to moment. I’ve been a fan since her early volume, Sappho’s Boat and thought Chelsea Girls was just terrific. For this reason the intimacy of these essays is very pleasing.

10

I’d have enjoyed the book more, I think, if I had not been reviewing it. Then I’d have read it much as any other reader would — abandoning some pieces without a thought, reading some because of some special interest in their subject, short ones when that was all there was time for. And so on. Or would I? Reviewing concentrates the mind; and in fact I tend normally to read from beginning to end, slogging away doggedly, or having a good time. (Myles says of herself that she, too, is that dogged sort of reader, needing to finish, unable to skip pages.)

11

Most pieces are in some degree narrative — either of incidents, or of the thinking’s circumstance and context. The writing has an enviable idiomatic sureness: the sentences, relatively unpunctuated, are pleasurably easy to read and their timing, pacing, weight, their brevity or sense of building — of approach and deflection, or of nailing it — makes them always expressive and alive. They uncurl, or snap or writhe, full of tone and attitude. I am under no delusions about Eileen Myles’ prose being within reach of my writing right here: she is lightyears ahead.

12

Myles’ political intelligence is always sharp and expressed in shorthand, but is accurate, perceptive, true — especially around issues of gender, difference and class, and ‘American-ness’. (There is, for example, the account of the Russian need to have only isolated gay celebrities, and to have them always confined to ‘the arts’ — there must never be a suggestion of gay numbers, of gay community, of gay normalcy — which is balanced against the telling American misogyny encountered casually (told casually) in an account of a tour by Sister Spit: amidst descriptions of the girls’ out-there clothes and dyed hair and loudness of manner is a male reaction at a Missouri highway diner, where they are all happily in possession of a big table: “Sini was getting something from the van and she overheard a guy in the parking lot say: ‘I’d like to put a bullet in each one of their heads.’ For being female on the road. For being a crowd of hungry women. For feeling good, and being loud. A totally American crime.” Then the story moves on.)

13

Myles, by the way, maintains great sang-froid throughout the book. She knows it’s a no-no to ‘protest too much’; she assumes we see her point without her highlighting it. Hence the ‘shorthand’ registration of incident, or of knowledge deduced or corroborated. I remember the word “patriarchy” coming up only a single time (and she adds, “there, I said it” — or something to that effect). Hmm, have I not mentioned the word “lesbian” yet?

14

Eileen Myles is gay and thinks interestingly and engagingly about it, interacts (interestingly, engagingly etcetera) with the female gay community, writes well about it. There are extended pieces of writing about gay or lesbian worlds and issues, but it comes up incidentally throughout, and it is always telling, what is said. In the ‘Iceland’ essay, for example, Myles is describing her movements about the country: she forces herself to go beyond the indicated tourist points of interest, sometimes finding herself trundling uncomfortably along in the wrong clothes with a dud suitcase wheeling behind her, feeling herself an idiot and, basically, rather abject. It’s funny to read. She hitches a lift with a cheerful truck-driver and at some point falls asleep. She remarks that she wakes feeling that she has been doing a very male thing: a woman is pitiable (as well as vulnerable) if she sleeps observed, in public, drooling — but a man can do it, no shame. In Iceland she finds she feels secure in a way that she wouldn’t at home. (Though is this stated? Maybe not.)

Waterfall, photo by Eileen Myles

15

That is Egil’s Fjord. Do you know Egil’s saga. Well I know some of the sagas. I’ve heard of it. He smiled. I even napped. In the bright lichen-covered landscape. I bobbed and drooled. It sounds like a baby but I think I felt like a man. I think a man is safe like this in the world and a woman never is. So it was a masculine feeling when I woke up. I opened my eyes. And there it was again. Magnificent. A waterfall. And then he stopped.

16

Travel throws America into relief, obviously. Iceland is a ‘new’ country, relatively unspoiled, relatively egalitarian. Myles worries will global capitalism render it as the US, she says, has become, a kind of nowhere, somewhere that is generic and resembles everywhere else. The book’s own sales pitch is accurate: “these essays posit inbetweenness as the most vital position from which to perceive culture as a whole, and a fluidity in national identity as the best model for writing and thinking about art and culture”.

17

Traveling or everything it seems is is very lonely. Until I realized I can just rent a film every day. I can always watch television And be with my family. In the flicker of the hearth. … The movies are all in English — the subtitles in Icelandic. So everyone is watching a subtitled film but me. Everywhere in the world. This is not supposed to be something to cheer about but it is a bland American premium. We may not have health insurance but we have made our language the equivalent of free hot dogs everywhere. For us. I was reading The Uncertain States of America where Paul Chan quotes Walter Benjamin saying that “places’ are melancholy. I’m saying something slightly wider. Life is melancholy now. Only in pictures do we free ourselves. So I’m puzzled by my inability to pick up a camera though on the boat I write” …

18

Some pieces are included for the author’s personal satisfaction at endorsing particular artists and their associated causes and coteries. And the art writing section is the least interesting: the narrative always runs on Myles’ experience of the work, but almost resolutely outside art-world usages: not a lot of description of the works, not much comparison made with like work, or pointedly differing work. The essays mostly centre on her own mood. They’re deft and graceful enough but don’t put the work clearly in our sights.

19

The essay on Robert Smithson seemed a good one — and gelled with my response to his early work. (Myles remarks on the bleak melancholy of the mirrors-in-the-desert photographs.) The section drawn from her blogs was often more acute about art than were her appreciations of Nicole Eisenmann or Sarah Rapson. On Rapson, for example: “To be real she explains. I’m not a painter to do a big abstract thing, a huge single effort, but I’m fooling around with that. She smiles. These are sheets she points out and looking closely at the painting’s edges you see the faint blue lines of its trim. Someplace there’s a scorch which implies ironing board. It’s not an ironic attempt to aestheticize domesticity, but a lumpily awe-inspiring job. Is it possible to feel like something’s rubbing from inside.” The spare punctuation is terrific, I think, and is pretty much the rule throughout the book. But it’s not great art criticism. It’s not Peter Schjeldahl. Though whom would I rather read than Schjeldahl on art, anyone?

20

The section under the heading ‘People’ was least interesting. Eileen Myles does a few people well: but mostly in the other sections. Daniel Day Lewis? Who cares? The flavour of a meeting with Ted Berrigan and his feelings about The Sonnets was good. It was nice to read about Schuyler’s hugely attended first and last reading.

21

There is a curious insistence on Myles’ status as a poet, that seems insecure and occasionally can read as rank-pulling mystification. Or is it defence? But as I write and type this copy up and read a bit more — pages I haven’t, in this first draft, got to yet — I come across Myles confessing to this herself, to the insecurity, at least. It’s in a very amusing article about flossing, flossing as symptom of and as metaphor for becoming adult, for deciding to live rather than die burnt out and young. In this instance, of course, it is part of that more usual worry about ‘stages’ in one’s life:

22

I don’t know about anyone else but when I found myself at the age of 33 no longer spending the majority of my days getting hammered I was to say the least perplexed. I never thought I wanted to DIE. That was not the point of my constant drinking … My father didn’t mean to make me watch him die. It just happened. But this next act, the living, this was conscious. This was a choice. Or that’s what I grappled with for a very long time. Do I want this. Being sober made me want to die. Cause I was swarming with feelings. About being a dyke. About being poor. About aging. About my inability to connect. About what a great poet I was, but what if — I don’t know, first what if I can’t write anymore, then what if no one will publish my work. None of these worries are particularly interesting or unique but I found myself in a state of endless worry. … And yet I had a simple urge to preserve what I’ve got.

23

Flossing. As is usual the essay belies the lite-ness implied by the title.

24

The mystificatory tendency — or is it a ‘move’? — might also be Myles’ way in, a device for bringing her closer to the mystery, the ineffable that — when she can do it — can become available to her through this guilefully guileless approach. The approach is a ritual of beginning that probably never guarantees an outcome or that makes its circuitousness or, alternatively, its quick release, predictable. There are occasions where the approach works and others where it doesn’t. It’s one of the few things I don’t like in the writing — not that I’m declaring for adamant certainty and ignoring ‘that of which we cannot clearly speak’. The verdict — on the book, I mean, not on this issue — Highly Recommended.

Ken Bolton, photo by Suzanne Treister

Ken Bolton runs Adelaide’s “Dark Horsey”, the bookshop of The Australian Experimental Art Foundation and runs also, intermittently, The Lee Marvin readings. His most recent collection since 2006’s At The Flash and At The Baci is A Whistled Bit Of Bop (Vagabond, 2010). Also just published is Bolton’s The Circus (Wakefield Press). A selection of his art criticism as it applies to art in Adelaide was published in 2009 by the Contemporary Art Centre of South Australia as Art Writing. Also in the offing — from Puncher and Wattmann — is Sly Mongoose. You want more? -go to http://april.edu.au/